Visual Representations in Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf and The New Women’s Movement

Introduction

The late 1890s was a transitional period in history that saw the rise of The New Women’s Movement, encompassing women who pushed back against the behaviours conventionally see as feminine by advocating for equal rights in areas of suffrage, education, and employment. Ideas behind the growing New Women’s Movement spilled into literary texts and illustrations of the time, such as Clemence Housman’s feminist text, The Were-Wolf (1896), which contains six illustrations by her brother, Laurence Housman. Using these images, this research project argues how the Housman siblings deliberately illustrate the female were-wolf White Fell as androgynous and transformative in order to illuminate the sociocultural anxieties that surrounded The New Women’s Movement in the 1890s. Through visual representations of White Fell, Christian, and Sweyn, the Housman siblings produced a socially driven work that ultimately supports The New Women’s Movement and implicitly calls for change in their society. This research exhibit will analyze three illustrations from the 1896 Bodley Head edition of The Were-Wolf: The Race, The Finish, and Sweyn’s Findings. In doing so, this project seeks to contribute to the broader significance of The Were-Wolf by highlighting the novella as a historical feminist text that accurately depicts its sociocultural moment of production.

Synchronic Analysis and Context: 1890s

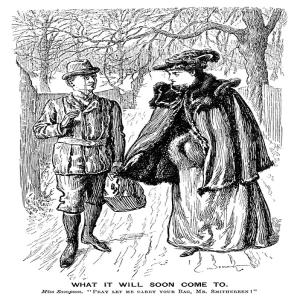

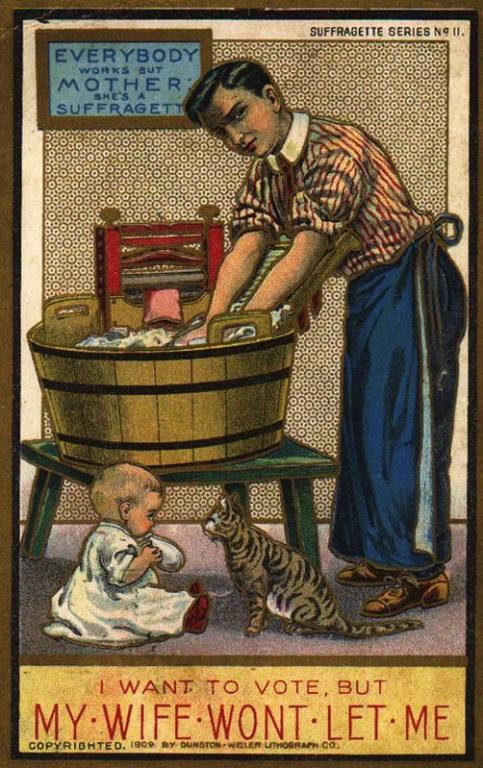

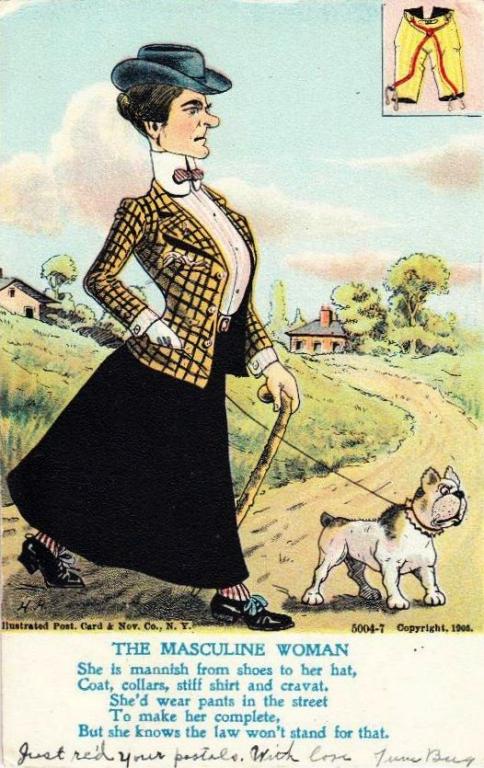

Late nineteenth-century Britain was a changing place and encompassed a variety of factors that helped The New Women's Movement grow. An economic boom from the industrial revolution created a rising middle class, a higher standard of living, and greater economic opportunities for men and women that changed the Victorian family structure (Clemons 1). Women rejected the patriarchal Victorian gender ideal of the obedient wife and mother and turned towards the figure of The New Woman, popularized by different feminist texts of the time. As a result, the growing New Women’s Movement created a gender panic that the British media took advantage of. Through newspapers and magazines (Figures 1, 2, & 3), the media constructed the New Woman as a man-hating third sex bent on destroying Victorian manhood and the patriarchy.

Figure 1. Illustrated poster. “Victorian New Woman Cartoon from Punch Magazine.” Circa 1896, insert. Public Domain. Punch Photo Shelter.

Figure 2. Illustrated poster by Dunston-Weiler. “The Suffragette Series N9 11.” 1909, insert. Public Domain. The Society Pages.

Figure 3. Illustrated postcard. “The Masculine Woman.” 1905, New York, insert. Public Domain. The Society Pages.

These depictions terrorised the Victorian public and fed into their fears of women’s rights (Clemons 1). In reality, New Women were professional career women who joined the public sphere by working as typists, secretaries, wood engravers, and writers, proving that women could fit into British public life (Clemons 2). Many of these women also advocated for women’s rights in areas of suffrage and education and sometimes sported short hair, wore divided skirts, and rode bicycles. It is important to note that Clemence Housman herself was a New Woman and her close brother Laurence Housman also supported the women’s rights movement. Both siblings resisted the gender constraints and binaries of their time, see with Clemence’s appearance (Figure 4), her wood engraving career, her choice of feminist magazine Atlanta for the first publication of The Were-Wolf (1890), and her later activism with the suffrage movement.  Figure 4. Photograph. “Laurence and Clemence Housman.” Circa 1910, London, insert. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 4. Photograph. “Laurence and Clemence Housman.” Circa 1910, London, insert. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons.

Similarly, Laurence resisted conventional expectations of Victorian manhood through his passion for aesthetics, the suffrage movement, and support for Oscar Wilde following his 1895 imprisonment for homosexuality (Browne). For over seventy years, the Housman siblings lived together as a sibling couple and collaborated on books and political projects, challenging the heterosexual and gender conventions of the typical Victorian family (Kooistra, “Querying Transgression” 58). This resulted in The Were-Wolf being a highly collaborative project between the siblings, including the six illustrations engraved by Clemence, which all reflect the content of her novella. Considering how both siblings resisted the gender conventions that governed their time, it is reasonable to read The Were-Wolf and its illustrations as a deliberate representation of the aspects of fen de siècle culture that the Victorians feared (Browne).

The Race

Figure 5. Illustrated by Laurence Housman, wood-engraved by Clemence Housman. "The Race." The Were-Wolf, 1896, p. 80., Insert. Public Domain. Cove Editions.

One such example of this deliberate representation is the illustration, The Race (Figure 5), which symbolizes how Victorians feared and resisted The New Woman and changing ideas behind gender binaries. In this illustration, Christian is running after werewolf White Fell to slay her and save his brother Sweyn from being her next victim. White Fell, who is “half masculine, yet not unwomanly” (Housman 23) fiercely independent and athletically gifted, represents the strong and deviant New Woman the Victorians feared. The depiction of White Fell transforming into a wolf and fully bestial from the waist down is significant. In gothic literature, the use of monsters reflects the fears of society as they often possess traits that are threatening or frightening (Biemans 9). The trope of the monstrous female were-wolf in particular, transgresses the boundaries between feminine and masculine binaries, as the primal behaviour of a were-wolf is conventionally masculine (Biemans 7). By depicting White Fell in mid-transformation, the Houseman siblings use her monstrous form as a safe and accepted vehicle to represent the “masculine” New Woman who challenged male dominance and repressive gender norms in Victorian society. White Fell’s form of half monster and half women ultimately symbolizes how the behaviours of The New Woman were threatening and frightening to the public. Further, the depiction of White Fell running from the Scandinavian town and into the outside woods while being pursued by the male Christian represents how patriarchal Victorian society resisted New Women by constructing them as outsiders to British society.

It is important to note that the character of Christian conforms to some male gender roles such as refusing to strike White Fell in her womanly form and taking on the protective responsibility of slaying the deviant werewolf who has invaded his town (Housman 87). However, Christian also possesses many effeminate behaviours that place him outside his assigned gender role, such as his lack of athletic skills and his emotional side, especially when juxtaposed against the hyper-masculine Sweyn (Housman 33). When considering Christian to be an outsider to his gender role, it is, therefore, significant that White Fell and Christian are in equal stride with neither character emerging victorious. The title of the illustration, “The Race,” further emphasizes their equal position when traditionally, the male would outrun the female. Their equal stride ultimately represents a destruction of both the traditional male and female gender roles that seek their conformance throughout the novella, connecting them as the outsiders and androgynes in their patriarchal society.

The Finish

Figure 6. Illustrated by Laurence Housman, wood-engraved by Clemence Housman. "The Finish." The Were-Wolf, 1896, p. 102., Insert. Public Domain. Cove Editions.

In the illustration The Finish (Figure 6), the Housman siblings depict the transformative White Fell in a position of power to implicitly support the New Woman and her resistance against repressive gender norms. This illustration depicts White Fell in a power stance over Christian who lies vulnerable and injured beneath her. White Fell’s transformation into a werewolf is nearly complete—with the only human skin showing on her hands and face. White Fell’s arched left hand is back in the air and is moments away from striking Christian with her ax (Housman 101). As discussed above, The Housman’s’ decision to depict White Fell as a transforming werewolf is significant as the lycanthropic transformation symbolizes the transgression between female and male binaries and the societal fear of the “masculine” New Woman (Biemans 7). However, in this illustration, in particular, White Fell’s transformation also symbolizes how female gender roles of the time were transforming and moving towards more freedoms and equalities with the help of The New Women’s Movement. White Fell’s physical dominance over a vulnerable Christian strongly departs from the conventional ideal of femineity and further emphasises her as a personification of a New Woman. As seen in The Race, Christian as a character conforms to his assigned male gender role and also exists outside of it. However, in The Finish, the depiction of the male Christian lying defeated at the hands of The New Woman figure, White Fell, symbolizes a female victory over the patriarchal and repressive ideals that governed womanhood in the 1890s. However, in reality, while these repressive female gender norms were changing and improving with the various women’s’ movements of the time, they still heavily remained in various aspects of British society. When considering this, one can read The Finish as representing the Housman siblings' idealized hope that their society would one day move towards completely ridding itself of the repressive gender norms that governed women’s’ lives. It is important to note that this illustration is one out of the two illustrations Clemence Housman signed in the Bodley Head edition of The Were-Wolf. Clemence Housman signing The Finish highlights how this illustration, in particular, was especially important to her. As mentioned, Clemence Housman was a New Woman and pushed back against the patriarchal and conventional ideas of femininity that repressed her. The Finish functioned as an artistic device for Clemence (and Laurence) to take an implicit stance in support of The New Women’s Movement and create an idealized symbol for the future, where she and the millions of other women in Britain would triumph over the patriarchy and obtain the freedoms they were lobbying for.

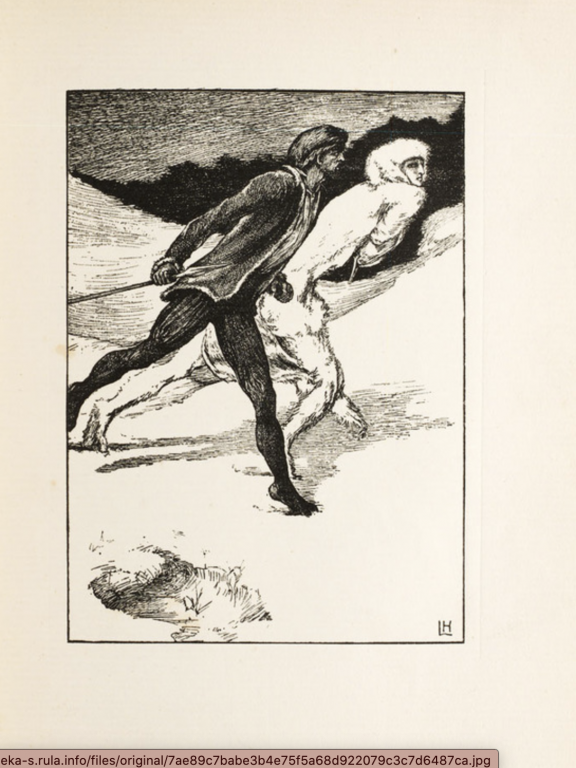

Sweyn's Finding

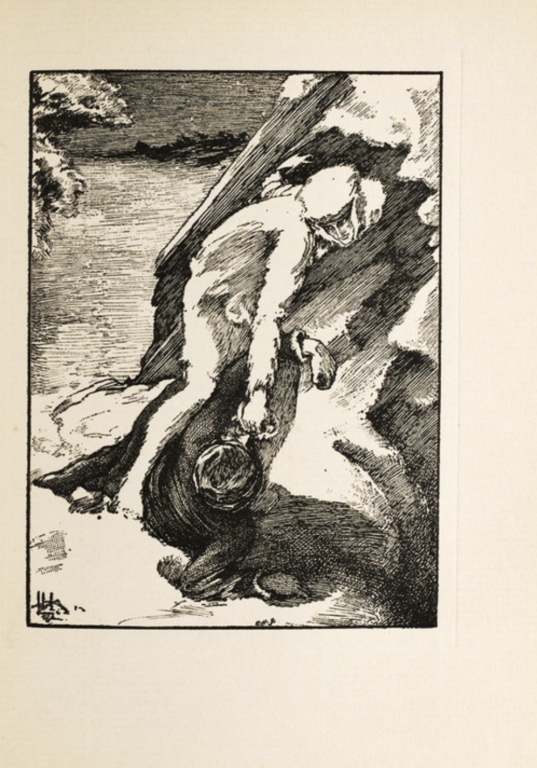

Figure 7. Illustrated by Laurence Housman, wood-engraved by Clemence Housman. "Sweyn’s Finding." The Were-Wolf, 1896, p. 116., Insert. Public Domain. Cove Editions.

While The Finish is a symbol of the Housman’s’ idealized hope for the future, the ultimate deaths of White Fell and Christian in the illustration Sweyn’s Finding (Figure 7), represent the reality of their society and act as a warning to those who blindly follow repressive gender ideologies. Sweyn’s Finding is the second illustration that Clemence Housman signed, again signifying the importance of this scene. Sweyn’s Finding depicts the hyper-masculine Sweyn lift his dead brother in lament. Nearby, White Fell lies dead in her full were-wolf form after killing Christian. The Housman siblings use this powerful final illustration to make a socially driven statement about the consequences that can arise from blindly following repressive gender norms and the harm that can come to those who resist them. As previously discussed, both White Fell and Christian represent androgynous forms of their assigned gender and are outsiders to their society. As such, it is significant that “both androgynes die, leaving the fully masculine man, Sweyn, to lead the community” (Kooistra, “Artist as Critic” 184). Sweyn’s ultimate survival in the image represents a social commentary on how the patriarchal man continues to lead British society even despite pushback from different movements of the time like The New Women’s Movement and The Aesthetic Movement. The deaths of both White Fell and Christian represent the Victorian’s resistance to androgynous figures and how this can have terrible consequences for the people who resist them. The death of White Fell, who perished for her bodily independence and freedom, holds particular significance as it symbolizes female freedom as something worth fighting for. This implicitly supports the New Women’s Movement and the many women in the movement who were fighting for more freedoms in Victorian society. Further, Sweyn’s Finding also highlights how public resistance against changing gender identities not only harms the androgynous outsiders but also the regular conforming citizens of Victorian society. While Christian is an androgynous outsider, he still tries to conform to conventional ideals of manhood by attempting to slay the deviant White Fell, a fact that ultimately leads to his death. This then leaves the hyper-masculine Sweyn to lead the town, who will continue to reinforce repressive gender ideals on his community that got his brother killed – perpetuating a vicious cycle of societal conflict and disharmony. Ultimately, the Housman siblings use Sweyn’s Finding as a symbol to call for social change in their society. Through the illustration, the siblings implicitly criticize traditional Victorian society and imply that in order to avoid unnecessary pain and suffering, society must learn to accept people of difference, including the changing ideals of womanhood.

Title Page

Figure 8. Illustrated by Laurence Housman, wood-engraved by Clemence Housman. "Title Page." The Were-Wolf, 1896, insert. Public Domain. Cove Editions.

Conclusion and Broader Significance

The sociocultural climate of late-nineteenth-century Britain was a changing one. An economic boom and a rising middle class gave more opportunities to women, who were rejecting the Victorian ideal of womanhood. Figures such as the fictional New Woman stood as a cultural icon for women to form a real-life New Women’s Movement, which took the form of women joining public life through employment and activism. However, the growing New Women’s movement gave way to societal fears and resistance against changing gender norms, fuelled by misconstrued media depictions of The New Woman. Considering that both Clemence and Laurence respectively resisted their assigned gender conventions that governed their time, their collaboration on The Were-Wolf (Figure 8) is an allegory of the aspects of the fin de siècle culture that the Victorians feared. This is especially seen in three notable illustrations: The Race, The Finish, and Sweyn’s Finding. In The Race, the Housman’s depict White Fell’s androgynous lycanthropic form as an accepted vehicle to personify the “masculine” New Woman and to symbolize the Victorian’s fear over the New Woman. In The Finish, the Housman’s continue this allegory by illustrating White Fell in a position of dominance over the male Christian, implicitly supporting The New Women’s Movement and symbolizing their idealized hope for a future without repressive gender binaries. However, the Housman’s represent the reality of their patriarchal society through the deaths of White Fell and Christian in Sweyn’s Finding, symbolizing the consequences that can come to those who blindly follow repressive gender ideologies. In doing so, the Housman siblings conclude their highly personal and collaborative novella with a socially driven statement that calls for Victorian society to accept people of difference and changing gender conventions in order to live in a harmonious society. Ultimately, The Were-Wolf stands as a historical feminist text that accurately reflects its sociocultural moment of production, especially seen in the three highlighted illustrations. In conclusion, this research project hopes to memorialize The Were-Wolf and its symbolism to aid modern readers in understanding the sociocultural climate of the 1890s and how this transitionary period impacted literary texts of the time.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.

Exhibit by Alessia Dickson

Works Cited:

Biemans, Roosmarjin. “When Women Were Wolves: The Representation of Feminism in Nineteenth-Century Werewolf Short Stories.” Leiden University: Leiden University Open Access, pp. 53-67., 2015, https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/34265/RDBiemans%…. Accessed 10 December 2020.

Browne Womby, Kate. “Representing the New Woman and Aesthete.” Edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Kate Womby Browne, et al., Cove Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/carving-out-space…. Accessed 10 December 2020.

Clemons, Vincente Edwards. “The New Women in Fiction and History: From Literature to Working Women.” Pittsburgh State University: Pittsburgh State University Digital Commons, pp. 1–98., 2016, digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1165&context=etd. Accessed 10 December 2020.

Dickson, Alessia. “Clemence and Laurence Housman Found the Suffrage Atelier – 1909.” Cove Editions, 2020, https://editions.covecollective.org/chronologies/clemence-and-laurence-…. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Dunston-Weiler. “The Suffragette Series N9 11.” 1909, The Society Pages, https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2015/12/28/where-do-negative-ster…. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Housman Clemence. “The Were-Wolf.” Illustrated by Laurence Housman. John Lane at the Bodley Head, 1896, Cove Editions, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0. Accessed 10 December 2020.

Housman Laurence (illustrator) and Clemence Housman (wood engraver). "Sweyn’s Finding." The Were-Wolf, 1896, p. 116. Cove Editions, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Housman Laurence (illustrator) and Clemence Housman (wood engraver). "The Finish.” The Were-Wolf, 1896, p. 102. Cove Editions, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Housman Laurence (illustrator) and Clemence Housman (wood engraver). “The Race.” The Were-Wolf, 1896, p. 80. Cove Editions, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Housman Laurence (illustrator) and Clemence Housman (wood engraver). “Title Page.” The Were-Wolf, 1996, Cove Editions, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-0. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Illustrated poster. “Victorian New Woman Cartoon from Punch Magazine.” Circa 1896, Punch Photo Shelter, https://punch.photoshelter.com/image/I0000fbLNVdOjz.0. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Khan, Hadia. “Brief Biographies of Clemence and Laurence Housman.” Edited by Lorrain Janzen Kooistra, Hadia Khan, et al, Cove Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/brief-biographies…. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. "Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf: Querying Transgression, Seeking Trans/Formation." Victorian Review, vol. 44 no. 1, p. 55-67., 2018, Project Muse, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/726574/pdf. Accessed 10 December 2020.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “The Artist as Critic: Bitextuality in Fin-de-Siècle Illustrated Books.” Aldershot: Scholar Press, 1995.

“Launch of Atlanta.” Cove Editions, 2020, Cove, https://editions.covecollective.org/chronologies/launch-atalanta. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Photograph. “Laurence and Clemence Housman.” Circa 1910, London, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laurence_Housman_and_Clemence_H…. Accessed 11 December 2020.

Post card. “The Masculine Woman.” 1905, The Society Pages, https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2015/12/28/where-do-negative-ster…. Accessed 11 December 2020.