Representing the Fin-de-Siècle New Woman and Aesthete

Author and wood-engraver Clemence Housman (1861-1955) was a Victorian feminist who resisted and protested the restrictive gender constraints and social hierarchies of her time. Her various political and social affiliations and contributions are evidence of her beliefs. In 1909, Clemence established the Suffrage Atelier with her brother, Laurence Housman (1865-1959), where they both contributed towards the production and dissemination of feminist propaganda. An active member of the Women's Social and Political Union and the Women's Tax Resistance League, Clemence was clearly invested in advancing women's rights, and was joined by Laurence in this endeavour (Oakley 42, 76; L. Housman 97-8, 223, 285; Kooistra, Artist as Critic 129, 184-5; Joannou & Purvis eds. 71, 141; Liddington & Crawford 42-6; Kenyur-Hodgkins 33).

Figure 1. Photograph, printed, paper, monochrome, Laurence and Clemence Housman wearing suffrage badges and standing in front of a suffrage banner. LSE LIbrary. Wikimedia Commons

Figure 1. Photograph, printed, paper, monochrome, Laurence and Clemence Housman wearing suffrage badges and standing in front of a suffrage banner. LSE LIbrary. Wikimedia Commons

Lorraine Janzen Kooistra's essay, "Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf: Querying Transgression, Seeking Trans/Formation," provides a strong summary of references that indicate both siblings rejected the gender binary (3-4), a statement that is supported in a range of publications about the Housman family (L. Housman 104; Engen 28; Oakley 43; Weeks 118-27; Carpenter 132; Liddington & Crawford 41-2; Kenyur-Hodgkins 7). Clemence was a highly intelligent, fast-moving subject who defied traditional expectations of Victorian women through her dress, her work, and her refusal to observe rules prescribed specifically to women. Similarly, Laurence contrasted from conventional expectations of Victorian men through his passion for the beautiful. His support for Oscar Wilde following his imprisonment in 1895 for homosexual relations suggests that Laurence, too, renounced limitations on gender and sexual expressions (Oakley 42; L. Housman 155). To identify the siblings using fin-de-siècle terminology, Clemence was a "New Woman" and Laurence was an "Aesthete."

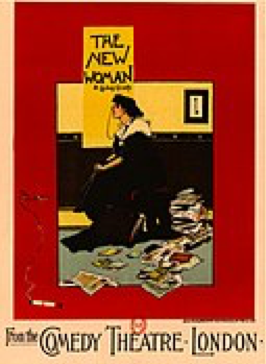

Although women did not necessarily identify with the term, the New Woman was a prominent figure of the late Victorian period (Richardson & Willis 1; Kooistra, Artist as Critic 109). Popularized by Sarah Grand in "The New Aspect of the Woman Question" (1894) and by Ouida in "The New Woman" (1894), the New Woman represented a growing demographic of women who saw no reason why they should be denied the rights of men, and who went about their affairs with disregard or even contempt for the restrictive list of attributes, behaviours, and responsibilities established as feminine and therefore ascribed to them as women.

Figure 2. “The New Woman.” Poster design by Albert Morrow, 1894. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2. “The New Woman.” Poster design by Albert Morrow, 1894. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Rejecting their assigned gender role and patriarchal society as a whole, New Women approached style, career, and romance with a rational bent. Signifiers of the New Woman included bicycles, cigarettes, divided skirts, and short hair—though this was arguably a construct of the proliferation of New Woman representations in fin-de-siècle culture (Richardson & Willis 13-26; Ledger, The New Woman 124). Seeking emancipation from the conventions that governed women for centuries, the New Woman served as an icon for an uprising of women who revolted against gender inequality by fighting for reform in the areas of work, education, marriage, and the right to vote.

Frustrations over gender inequality had been accumulating for over a century, since the publication of Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). The groundbreaking feminist work called out contradictory expectations of men and women, and advocated for women's right to education and employment—a remuneration, Wollstonecraft pointed out, that was commensurate with woman's role in educating future generations (Richardson & Willis 1; Mellor 153). These feminist beliefs began to spill over into fin-de-siècle literature and art (Kooistra, Artist as Critic 91). Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf appears to have followed this trend as well (Purdue 50).

The fact that Clemence remediated The Were-Wolf over a span of 40 years suggests the story was especially important to her. Knowing that Clemence herself was a New Woman and her brother Laurence was an Aesthete, perhaps this is what made The Were-Wolf so meaningful to her. In addition to participating in the fin-de-siècle women's rights movement, Clemence and Laurence Housman were both active participants in the period's Aesthetic Movement, which "not only encouraged artists to explore the impulses and desires that Victorian society preferred to conceal, but further freed them to take a stand against trends in society which threatened their personal freedom" (Kooistra, Artist as Critic 129). Given that Clemence and Laurence both demonstrated long-term dedication and passion in their support of women's rights and the Aesthetic Movement overall, it is reasonable to read The Were-Wolf as containing deliberate, embedded representations of the fears, double standards, and expectations of women and men that characterized this decade.

Through the masculinized White Fell and the feminized Christian, The Were-Wolf speaks to the plight of the New Woman and Aesthetes by placing these characters on the margins of the community within which the story is set. As Kooistra articulates, “[it is significant that] both androgynes die, leaving the fully masculine man, Sweyn, alive to lead the community” (Artist as Critic 184). Is death the punishment for women who reject feminine dress and dare make visible their sexuality? Are “effeminate” men destined for obsolescence?

Fitting neatly into nineteenth-century literary trends, Clemence uses the figure of the wolf and the genre of the supernatural to create a safe space for exploring characters that sit outside of gender conventions. Through White Fell, Clemence presents a strong, deviant, and bestial woman representative of the New Woman that Victorians feared. However, while other New Woman narratives typically present the leading female character as a seductive temptress or femme fatale, Clemence deviates from this with White Fell, who is instead pursued by the overtly masculine Sweyn. This is an important departure that might reflect the author’s feminist beliefs—if the New Woman was to be feared in part due to her sexual aggression, this is countered by the interplay between White Fell and Sweyn. Similarly, Christian—White Fell’s only fellow outsider or threshold figure in a patriarchal community—serves as a representative of the Victorian decadent, the Aesthete. In fact, White Fell and Christian can be read as androgynous inversions of each other, further emphasizing their connection as outsiders or deviants from dominant society (Kooistra, Artist as Critic 186).

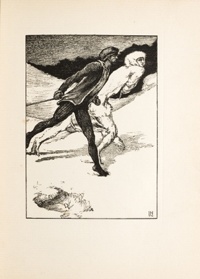

Figure 3. "The Race." Illustration by Laurence Housman, wood engraved by Clemence Housman

Figure 3. "The Race." Illustration by Laurence Housman, wood engraved by Clemence Housman

References to the dualisms and doublings between White Fell and Christian are made more explicit in The Bodley Head edition of The Were-Wolf (1896) through Laurence's illustrations, which play on their connection as threshold figures in solidarity with one another (Zigarovich; Oakley 52-3; Kooistra, Artist as Critic 189). This is captured most effectively in the illustration “The Race,” in which White Fell and Christian are depicted in equal pairing with one another, underscoring both a destruction of their assigned gender roles (where the male, Christian, would be expected to outrun White Fell, the female) and their recognition of something in the other that connects them as outsiders (Oakley 52). Interestingly, Christian is the only one who recognizes White Fell’s “true identity”—an insight he has as a result of his own social location outside of established gender norms.

The choice of publishers is perhaps revealing, too, of the intentions behind The Were-Wolf. It was first published in a Christmas 1890 edition of the progressive girls' magazine Atalanta, dedicated to empowering and educating young girls. Laurence then negotiated republication of the novella by John Lane at The Bodley Head (L. Housman 97-8). The Bodley Head was known for publishing controversial avant-garde material and had recently published Vernon Lee's "Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady" (1895), which tells the tale of a cursed snake lady who shows love to a handsome young prince. Not unlike The Were-Wolf (1896), Lee’s story is about aberrant female sexuality, power, and death. Mary Patricia Kane's essay, "The Uncanny Mother in Vernon Lee's ‘Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady,’" not only outlines Freudian interpretations of the novella, but also identifies a blurring or hybridity between what are traditionally understood as distinct categories: male and female, human and animal, East and West, and past and present (Kane 41). Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf and Lee's "Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady" were representative of many works by gender-non-conforming women writers published in the late nineteenth-century that explored anxieties around the New Woman under the guise of mythic creatures.

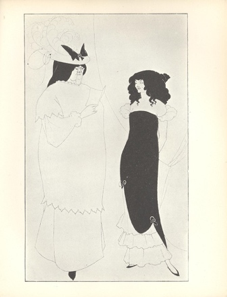

Figure 4. Aubrey Beardsley, "L'Education Sentimentale," The Yellow Book vol 1, April 1894. Yellow Nineties Online. www.1890s.ca

Figure 4. Aubrey Beardsley, "L'Education Sentimentale," The Yellow Book vol 1, April 1894. Yellow Nineties Online. www.1890s.ca

In fact, we see a concentrated example of these types of stories in The Yellow Book (1894-1897), a British quarterly periodical published by none other than the publisher of The Were-Wolf, The Bodley Head. The Yellow Book featured artwork by illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, a prominent figure of decadence. Lane had also recently launched the Keynote Series (1894-1897), a collection of thirty-four liberal novels and short stories all relating to topics concerning the New Woman, including Grant Allen's “The Woman Who Did” (1895), which had previously struggled to find a publisher (Stetz 72, 81; Warne & Colligan 21, 25).

The large quantity of New Woman fiction published by Lane implies a certain political lean or empathy towards the fight for women's rights, and The Bodley Head's focus on publishing belle lettres certainly supports Lane's reputation for advancing and appreciating aestheticism and decadence, or "art for art's sake." Sally Ledger's essay, "Wilde Women and The Yellow Book: The Sexual Politics of Aestheticism and Decadence," however, describes Lane as an opportunist in this regard, suggesting that he "was quick to exploit the success of the New Woman writing" (8).

Regardless of Lane's motivations, the fight for the legitimization of the beautiful and sensuous that marked fin-de-siècle Britain was tied to a broader resistance to assigned gender expressions, as seen in the phenomenon of the New Woman. The climate of oppressed gender expressions and societal fears about women's changing roles demanded such resistance, and feminist interpretations give weight to the theory that Clemence and Laurence Housman's collaboration on The Were-Wolf (1896) is a response to this shift. Perhaps the siblings used The Were-Wolf to carve out spaces for exploring New Women and Aesthetes—the gender nonconforming—in a manner that was not only accepted, but popular at the time.

Kate Womby Browne, Ryerson University, 2018

Citation: Womby Browne, Kate. “Representing the New Woman and Aesthete.” Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Kate Womby Browne, et al., COVE Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/carving-out-spaces-new-women-and-aesthetes

Works Cited

Carpenter, Edward. Love's Coming of Age: A Series of Papers on the Relations Between the Sexes. The Labor Press, 1896.

Engen, Rodney. Laurence Housman. Catalpa Press, 1983.

Housman, Clemence. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Everard Hopkins. Atalanta vol. 4, no. 39 Dec. 1890, pp. 132-56.

—. The Were-Wolf. With 6 illustrations by Laurence Housman engraved by Clemence Housman, John Lane at the Bodley Head, 1896.

Housman, Laurence. Unexpected Years. Bobbs-Merrill Co, 1936.

Joannou, Maroula and June Purvis, eds. The Women's Suffrage Movement: New Feminist Perspectives. Manchester UP, 2009.

Kane, Mary Patricia. "The Uncanny Mother in Vernon Lee's "Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady." Victorian Review, vol. 32, no. 1., 2006, pp. 41-62.

Kenyur-Hodgkins, Ivan G. Laurence Housman, 1865-1959, Clemence Housman, 1861-1955, Alfred Edward Housman, 1859-1935. National Book League, 1975.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. The Artist as Critic: Bitextuality in Fin-de-Siècle Illustrated Books. Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1995.

—. "Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf: Querying Transgression, Seeking Trans/Formation," Forthcoming in Victorian Review, 2018.

Ledger, Sally. The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siècle. Manchester UP, 1997.

—. "Wilde Women and The Yellow Book: The Sexual Politics of Aestheticism and Decadence." English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 50, no. 1, 2007, pp. 5-26.

Lee, Vernon. "Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady." The Yellow Book, vol. 10, July 1896, pp. 289-344. The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2013. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s+YBV10_lee_prince.html

Liddington, Jill and Elizabeth Crawford. Vanishing for the Vote: Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the Census. Manchester UP, 2014.

Mellor, Anne K. "Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and the Women Writers of Her Day." The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft. Cambridge UP, 2002.

Oakley, Elizabeth. Inseparable Siblings: A Portrait of Clemence and Laurence Housman. Brewin Books, 2009.

Ouida. "The New Woman." The North American Review, vol. 158, no. 450, 1894, pp. 610-619.

Purdue, Melissa. "Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf: A Cautionary Tale for the Progressive New Woman." Revenant, no. 2, 2016, pp. 42-55. http://www.revenantjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Article-3.pdf

Richardson, Angelique and Chris Willis, eds. The New Woman in Fiction and in Fact: Fin-de-Siècle Feminisms. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Stetz, Margaret Diane. "Sex, Lies, and Printed Cloth: Bookselling at the Bodley Head in the Eighteen-Nineties." Victorian Studies, vol. 35, no. 1, 1991, pp 71-86.

Warne, Vanessa and Colette Colligan. "The Man Who Wrote a New Woman Novel: Grant Allen's The Woman Who Did and the Gendering of New Woman Authorship." Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 33, no. 1, 2005, pp. 21-46.

Weeks, Jeffrey. Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain, from the Nineteenth Century to the Present. Quartet Books, 1977.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. Printed for J. Johnson, 1792.

Zigarovich, Jolene, ed. TransGothic in Literature and Culture. Routledge, 2018.