The Were-Wolf, British Folklore, and the Colour White

Despite—or perhaps because of—seeing a rapid technological and cultural acceleration towards the future, Victorians had a fascination with the past. We see this in the last Gothic-tinged gasps of Romantic nostalgia for a pre-industrial pastoralism, in the Pre-Raphaelite interest in medieval revival, and in the Arts and Crafts movement, which encouraged a return to a pre-industrial materiality. On a more domestic scale, we see this in a renewed interest in what seemed to be a vanishing national past connected to Celtic, Norse, and native British traditions (Silver). The folk traditions and mythological context that inform Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf vary widely. Given that folklore is one of the ways in which humans rationalize the unknowable (and thereby the frightening), Housman’s use of the colour white in her horror story is particularly interesting.

The colour white is part of the mythology of the British Isles in a way that few other colours are. The oldest known name for the island of Great Britain is “Albion,” which comes from the same Indo-European base that provides the Latin albus, meaning “white.” The name may derive from the first thing a visitor arriving by sea would see: the chalk cliffs of Dover, which have themselves become a national symbol. A geoglyph of a white horse in Uffington dates to at least three thousand years ago, and requires regular maintenance in order to not be covered with grass, creating a literal and ongoing connection between the people of the area and the whiteness of the land beneath the grass.

Figure 1. Wendy North, White Horse at Uffington. Wikimedia Commons

Figure 1. Wendy North, White Horse at Uffington. Wikimedia Commons

We can also see the colour white in a less-geographical context. On a variety of coats of arms, a white unicorn represents Scotland (also known by romantically-minded folk as “Alba”). This is not the only supernatural white animal to be found in British culture; a myriad of white swans and white harts grace the signs of public houses and hotels throughout the country. A disagreement between correspondents in the Victorian magazine Notes and Queries some thirty years before the publication of The Were-Wolf over the origin of the “Sign of the White Hart” refers to the urban legend that the name is from a country squire’s hunting of a white doe (E.K., Wads.). Arthurian mythology has Merlin dreaming of a white dragon and a red dragon fighting underground (Schwyzer 21). Here, the white dragon represents the Anglo-Saxons and the red the Britons; the Anglo-Saxons, it is worth noting, originated in the same Nordic area in which Housman set The Were-Wolf. White, to the British Victorian reader, is a magic colour.

Figure 2. Keith Evans, White Hart Inn Sign. Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2. Keith Evans, White Hart Inn Sign. Wikimedia Commons

There is a lot of whiteness in The Were-Wolf, both as a text and in the werewolf herself. Not only does Housman’s werewolf initially appear as a “white-robed woman . . . very fair” and later become a white wolf, she is also named “White Fell” by “the folk of this country” (22, 23, 26). This is an immediate clue that the mysterious visitor is more than she seems, as she is placed firmly in the British tradition of supernatural white creatures. Housman’s choice to have her werewolf be female provides an additional clue; the Northern parts of England and Scotland have stories of a White Lady who is either a ghost or a witch depending on location (the story itself has variants all over the world). In the English West Country, stories abound of a white hare who is the ghost of a wronged woman, returned to steal the soul of the lover who betrayed her. The resonance with The Were-Wolf is obvious; White Fell is a dangerous woman for men to be around, and she puts at risk the souls of any who get too close.

Figure 3. Everard Hopkins's illustration for Atalanta (1890) showing White Fell and Little Rol

Figure 3. Everard Hopkins's illustration for Atalanta (1890) showing White Fell and Little Rol

The first to die in The Were-Wolf is little Rol, who is infatuated with White Fell and is the first to touch her white robe. This ties in with the connotation of white as an omen of death. Folklore holds that white horses are ominous to meet and that white flowers, especially snowdrops, foretell death, with some few exceptions (Briggs). Housman uses this association to increase the sense of inescapable doom through White Fell’s pale other-worldliness and through the landscape. Housman sets her story in a Scandinavian winter and makes frequent reference to the weather; the term “snow” appears 39 times in the story, and is referred to obliquely several other times, as in “the untrodden white” (20).

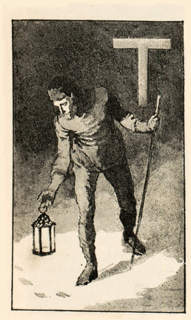

Figure 4. Everard Hopkins's historiated initial letter for Atalanta (1890), showing Christian tracking the wolf tracks in the snow

Figure 4. Everard Hopkins's historiated initial letter for Atalanta (1890), showing Christian tracking the wolf tracks in the snow

The characters are at all time surrounded by whiteness in a very literal sense. The only scenes in which the characters are not immediately surrounded by snow are the ones in which they are indoors, and even then they are in a small, snow-locked building. It is the snow that provides the first concrete evidence (as opposed to evidence by inference) that White Fell is unnatural. Christian first encounters her by noticing that “in the snow [is] the track of a great wolf,” which he follows all the way to the door, which is where the “snow [fails]” (31). Housman deliberately uses the word “failed” instead of saying that the snow “stopped” or “ended.” When Sweyn says that “snow is falling fast” and “not a single light to be seen,” then the white of the snow becomes associated uncharacteristically with darkness, which, together with its previous failure, has an unsettling effect (44). Snow is falling; white falls.

Clemence Housman wrote The Were-Wolf for a Victorian British audience and in doing so, took full advantage of that audience's fascination with the national past and folklore. These are all stories that Housman’s audience would have had told to them as children and been enthralled with as adults. By choosing white as the colour of her werewolf, Housman ties White Fell to the land and to the supernatural in the mind of her reader. A story happens in the space between the book and the reader and is composed of the text and what the reader themselves brings with them into the narrative. Housman makes use of her audience’s pre-held associations to heighten the tensions and the horror inherent in her story; the land becomes dangerous, and death begins to seem inevitable.

Emily C. Fleming, Ryerson University, 2018

Citation: Fleming, Emily C. "The Were-Wolf, British Folklore, and the Colour White." Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Emily Fleming, et al, COVE Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/were-wolf-british-folklore-and-colour-white.

Works Cited

Briggs, Katherine Mary. The Folklore of the Cotswolds. Rowman and Littlefield, 1974.

Briggs, Katherine Mary, and F.J. Norton. A Dictionary of British Folk-tales in the English Language, Incorporating the F.J. Norton Collection. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970.

“E.K.” “The White Hart at Ringwood.” Notes and Queries, vol. 9, no. 3, 1866, p. 293. http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/ilej/pbrowse.pl?item=title&id=ilej.1....

Housman, Clemence. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Everard Hopkins. Atalanta, vol 4, no. 39, Dec. 1890, pp. 132-156.

---. The Were-Wolf. With 6 illustrations by Laurence Housman engraved by Clemence Housman. John Lane at the Bodley Head, 1896.

Schwyzer, Philip. Literature, Nationalism, and Memory in Early Modern England and Wales. Cambridge UP, 2004.

Silver, Carole G. Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness. Oxford UP, 2000.

“Wads.” “Origin of the Sign of the White Hart.” Notes and Queries, vol. 8, no. 209, 1865, pp. 536-537. http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/ilej/pbrowse.pl?item=title&id=ilej.1....