Lycanthropic Women and Victorian Sexual Dissidence

Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf is embedded within the fin-de-siècle sexual discourses that dominated the culture at the time of its publication. In particular, White Fell exists as a liminal figure, whose transition between human and animal reflects a transgression of concepts regarding gender difference and sexuality that shaped the traditional Victorian social identity. Situated within the proliferation of nineteenth-century lycanthropic fiction, Housman's werewolf represents the disruption of such normative boundaries.

The 1890s was a period of categorical crisis for the sexual body, when dominant discourses about what it meant to be a man or woman were fiercely contested. A series of sex scandals in public print placed pressure on the laws that had previously governed sexual behaviour. The figure of the New Woman was one prominent example of how the roles of women became a subject of debate (Pykett 138). Her androgynous style of dress and independence from the domestic ideals of womanhood circulated in magazines as a beacon of progress for her supporters, and as a cultural demon to her opposers (Pykett 139). Erotic desire was similarly called into question by the presence of homosexuality in the public consciousness. Late-Victorian medical sexological writing “invented” the homosexual as a separate species from the normative heterosexual identity, further embroiled by legal cases that revealed public homosexual behaviour, male brothels, and the sodomite acts of upper-class men (Kaye 60-2).

This contestation of binaries informed tropes of transformation in nineteenth-century literature. Supernatural fiction in the 1890s often focused on the transmutation of one form to another, combining metaphors of animality with the degeneration of the mind and body, of which wolves were an especially popular theme (Youngs 4). The werewolf, a hybrid of animal and human, emerged in most narratives as a creature that symbolized fears of the uncivilized inner beast and aggressive, self-indulgent sexual gratification (Frost xi). Housman’s werewolf character, White Fell, acts as a personification of such anxieties. In taking up the literary themes associated with this particular creature, Housman participated in the dissemination of a myth meant to explore the liminal spaces of sex and identity.

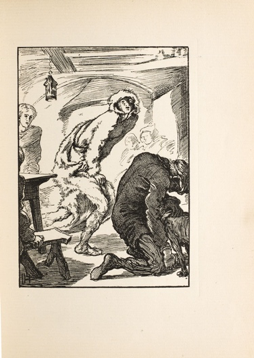

Figure 1. Laurence Housman, "White Fell's Escape"

Figure 1. Laurence Housman, "White Fell's Escape"

This is demonstrated in the appropriation of female sexual aggression into the figure of the werewolf, configured as a form of femme fatale whose sexuality was a defining element of their monstrosity. The 1890s brought multiple representations of wolf-women, all of whom repeated similar conventions. In contrast to their male counterparts, nineteenth-century female werewolves often disguised themselves as beautiful women seeking to deceive and devour unsuspecting male lovers (Du Coudray 47). These monsters used sexual manipulation to both attract their victims and ensure their death. Preceding White Fell, Ravina in Gilbert Campbell's “The White Wolf of Kostopchin” presented a literalization of this trope by tearing out her lover's heart (Frost 78). Housman's werewolf engages in similar sexualized hunting behavior in the form of her deadly kiss, through which she marks her future victims, including her would-be suitor, Sweyn (Housman 73). In such narratives, female monstrosity is constituted by a subversion of desexualized femininity, which in turn threatens the lives of a male dominated society. In the midst of a moral panic regarding female sexual autonomy incited by figures such as the New Woman, the 1890s female werewolf also derived horror from its own sexual deviance. Thus, dramatized in White Fell's atavistic sexuality are the anxieties about greater sexual freedom that threatened the Victorian ideal.

The disruption of fixed gender identities in The Were-Wolf is also articulated in the hybridity of the werewolf myth itself. In transgressing the boundaries between human and animal, White Fell refuses to participate in categories of natural order. Throughout the text, the character Christian situates her within that liminal space, referring to her as a Thing that merely appears to be female (Housman 32). However, transformation visualized the conflation of normative boundaries, wherein a violation of the physical body signified an alteration to the social body. Other woman-animal transformation stories provided a literary tradition through which to resist the expectations of gender by having the subjugated female body be replaced by that of a beast (Lönngren 88). In Ambrose Bierce's “The Eyes of the Panther,” an example of a feline variant of werewolf fiction, Irene Marlowe's resistance to the demands of her suitor's marriage proposal culminates in her attempt to devour him in the degenerated form of a large panther (Bierce 9). Such stories employed Gothic horror's use of the grotesque to portray a discursive struggle to claim the civilized self through an abjection of the Other (Punter and Bryon qtd in McMahon-Coleman and Weaver 68).

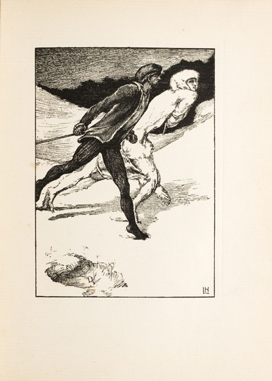

Figure 2. Laurence Housman, "The Race," showing White Fell as a hybrid woman/animal in the process of transformation

Figure 2. Laurence Housman, "The Race," showing White Fell as a hybrid woman/animal in the process of transformation

Thus, White Fell's own transformation similarly imagines a body divided against itself. Her race with Christian continuously refers to her unnatural shift from a woman into a wolf, until she devolves into her lupine form upon her death (Housman 106). Unable to reconcile her duality, White Fell interferes with the normative binary systems of human and beast, thereby occupying a space where she is bound by neither identity. Much like lycanthropic monstrosity, the social identities of the sexually ambivalent New Woman and the homosexual were formulated as disruptive to the status quo. Their sexual fluidity blurred the conceptual boundaries of the Victorian ideal, creating something alien. Nineteenth-century werewolf fiction drew upon such perceived corruption in parts of the community to construct its monsters, utilizing binaries of race, gender, and animal physiognomy to imagine these identities as a composite Other (Du Coudray 44-5). White Fell speaks with a foreign accent, marking her as an outsider (Housman 24). Other werewolf stories, such as Eric Stenbock's “The Other Side,” turn this binary into a literal divide between a human and lycanthrope community (Stenbock 270). Within the Victorian werewolf narrative, to engage in transformation was to risk the displacement of one's relationship with society.

White Fell is therefore constructed as a chaotic figure, whose unstable intersections of body and identity combine fears of physical degeneracy with the violation of fixed Victorian social structures. By participating in the many conventions of fin-de-siècle werewolf fiction, Housman simultaneously contributed to the period's discourses of transformation and sexual selfhood. The werewolf remains a Gothic icon, but situated within the cultural context of the 1890s, it marked the appropriation of a myth for the expression of sexual dissidence.

Mary Ann Matias, Ryerson University, 2018

Matias, Mary Ann, “Lycanthropic Women and Victorian Sexual Dissidence.” Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Mary Ann Matias, et al, COVE Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/lycanthropic-women-and-victorian-sexual-dissidence.

Works Cited

Bierce, Ambrose. “The Eyes of the Panther.” 1897. The Moonlit Road and Other Ghost and Horror Stories, edited by Paul Negri, Courier Dover Publications, 2015, pp. 1-10.

Du Coudray, Chantal Bourgault. The Curse of the Werewolf: Fantasy, Horror and the Beast Within. I. B. Tauris, 2006.

Frost, Brian J. The Essential Guide to Werewolf Literature. Popular Press, 2003.

Housman, Clemence. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Everard Hopkins. Atalanta, vol 4, no. 39, Dec. 1890, pp. 132-156.

—. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Laurence Housman, John Lane, The Bodley Head,1896.

Kaye, Richard. A. “Sexual Identity at the Fin-de-Siècle.” The Cambridge Companion to the Fin de Siècle, edited by Gail Marshall, Cambridge UP, 2007, pp. 53-72.

Lönngren, Ann-Sofie. Following the Animal: Power, Agency, and Human-Animal Transformations in Modern, Northern-European Literature. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015.

McMahon-Coleman, Kimberley, and Roslyn Weaver. Werewolves and Other Shapeshifters in Popular Culture: A Thematic Analysis of Recent Depictions. McFarland, 2012.

Pykett, Lyn. The "improper" Feminine: The Women's Sensation Novel and the New Woman Writing. Psychology Press, 1992.

Stenbock, Eric. "The Other Side: A Breton Legend." 1893. A Lycanthropy Reader: Werewolves in Western Culture, edited by Charlotte F. Otten, Syracuse UP, 1986, pp. 269-285.

Youngs, Tim. Beastly Journeys—Travel and Transformation at the fin de siècle. Liverpool UP, 2013.