Transforming The Wolf in Words: White Fell and The Importance of Names

The right name for a character can reveal everything about who they are, and how important they are to a story. In Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, there is no mistake that every name is exceptionally important. Take, for instance, the werewolf White Fell. She blows into the lives of Sweyn and Christian, and only produces for them a vague double-entendre name by which they can call her. “‘My real name,’ she said, ‘would be uncouth to your ears and tongue. The folk of this country have given me another name, and from this’ (she laid her hand on the fur robe), ‘they call me ‘White Fell”’ (24-25). The locals call her “White Fell” because of the pelt of white fur that she wears, she tells the household. What is not immediately uncovered is the other meaning hidden in her name: that “fell” also refers to something “of terrible evil or ferocity; something deadly.” This duality is reflected also in the nature of who she is: a werewolf, a monster caught in constant hybridity.

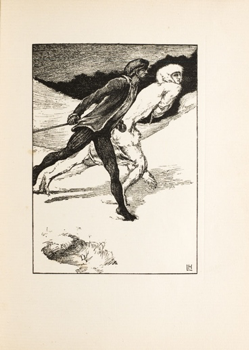

Figure 1. White Fell in the process of transforming from woman to wolf in “The Race” (1896). Wood engraving by Clemence Housman after Laurence Housman’s design.

Figure 1. White Fell in the process of transforming from woman to wolf in “The Race” (1896). Wood engraving by Clemence Housman after Laurence Housman’s design.

In Old English, man or mon denoted a person of any sex. It was a genderless noun, similar to how mankind is often accepted as a genderless noun. The prefix wo in “woman,” that first morpheme, is derived from the Old English wyf. Wyf once had a history of being used only when referring specifically to “female human beings,” and as the word persisted throughout history it eventually became the root of the word “wife.” Its grammatical gendered equivalent—despite having fallen out of popular use because of the redundancy of man being both the hypernym for all people, and eventually the hyponym of men as a sex—was wer.

Wer is a bit trickier. It has been accepted as both an equivalent of “male human” and “husband,” and has been spelled both wer and were, although the latter spelling is infrequent and when employed normally refers to a “troop” (Bosworth and Toller). Visually, the written script of were is more recognizable than wer in the application of the word to an etymological origin for “werewolf.” But almost no dictionaries report with any conclusiveness that wer is the sole or true root of “werewolf,” and the skepticism surrounding the dating of the word exists because there is only one appearance of the word “werewulf” in any Old English text. Other ancient languages all contain evidences of their own use and spellings of werewolf, but with only one Old English example, it complicates the history of the word and makes it difficult to suggest, accurately, how truly old the word and its roots are.

And consider the monster. One root for “monster” is monstrum, signaling an omen, if from the gods (Biles 3). Monstrum comes from monere, a divine warning or advice; like prodigium, a possible synonym, which refers to something unnatural, signalling danger or disaster (Ingebretsen 211). To be a monster is to be a warning. To be a monster is to be the monstre, the deformed body warning of potential threat, of a change of fortune.

So, what does this mean for Clemence Housman’s character White Fell? First that a werewolf, a were-wolf, is the hybridic result of a man and a wolf—this is most evident. White Fell, however, is not a male human who was bitten by a beast and turns into a lupine creature under the full moon, but a wolf who can assume the form of a woman until midnight. Is it more accurate to call her wyf-wolf? “Wife wolf” sounds feeble and inaccurate, a gendered way to name a terrible monster. What of were-woman—a man-woman? White Fell is certainly of body and dress “half masculine, yet not unwomanly” (Housman 23). She is a prodigious athlete whose comely female form hides all the strength and violence that ripples underneath, that threatens, that recalls something more masculine than feminine. She is a creature in fluidity, who shifts between her two forms as easily as she shifts between gendered expectations. But even White Fell is not immune to the power of language and the way it enacts transformation upon those most monstrous messengers.

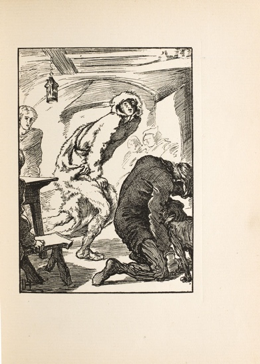

Figure 2. "White Fell's Escape." Wood engraving by Clemence Housman after Laurence Housman's design (1896)

Figure 2. "White Fell's Escape." Wood engraving by Clemence Housman after Laurence Housman's design (1896)

When asked about her name, White Fell calls her true name “uncouth to your ears and tongue” (Housman 25), a suggestion of alien-ness that defies description, beyond a human capacity to speak or hear it. “White Fell,” as a name, refers to two things. The first is fel, the Old English word for an animal’s hide or skin with its hair and a reference to the white fur outfit that our monster wears. Secondly, fell as an adjective refers to something of terrible evil. Even White Fell’s name is a warning: evil, wrapped in soft white fur; evil waiting beneath that fur. Her double name, like her two bodies, suggests good and evil; as a woman, she is a symbol of life; as a wolf, she is a symbol of death (Hodges 64). If Housman intended this in the tradition of true names, then obscuring White Fell’s true name not only obscures her true nature, but also her powers.

Words have a power that can be dangerous in the wrong hands. While fantasy writers like Ursula K. LeGuin are recognized as having popularized the magic of knowing the “true name” of someone or something, it is a tradition that predates nineteenth and twentieth century writers. A “true name” suggests that language, specifically sacred words and those used as names, can unlock the true nature of the thing named. Knowing and speaking the true name of someone gives one power over them, allows one to control them or alter them. The inclusion is relatively common in modern fantasy literature but comes from a long history in religious invocation, mantras, magic, philosophy, and other traditions.

One of the most explicit and powerful versions of this is found in the book of Genesis. Made in the image of God, Adam is master over all the animals, each of whom he names, and over whom he has dominion (Gen. 1.26, 2.20). Japanese Shinto beliefs include a similar version called kotodama, which refers to the spiritual power residing in words (Encyclopedia of Shinto). There are global examples of giving children multiple names and nicknames to protect them. Rumpelstiltskin’s story is about guessing the imp’s true name. The Egyptian god Ra came to fear Isis when he revealed his secret name to her (University College London).

Try as she might to obscure herself from being touched by this tradition, White Fell barely scrapes by. Like Nick Bottom in Shakespeares' Midsummer Night’s Dream, she is translated by others. New names are not uncommon for White Fell, and whatever uncouth name is in her origin, her body and flesh are transformed, altered with each new name given to her.

In Housman’s story, White Fell is continuously corporeally translated into what she is called by others: “white pelt” by villagers (26); “fell Thing,” “beast,” “Death animate,” and “She” by Christian (68; 93; 97; 106); “the Thing” by Sweyn (116). She is the monster, the threat. Cast off is the white robe that made her seem innocent. Gone is any relation to her humanness, her womanliness, her human body and its act as undercover agent. When White Fell is discovered and transformed by these names, she never fully returns to pretending to be the fair maiden made victim in Gothic stories—rather she embraces being the beast itself. White Fell is a creature of dual nature, a hybrid being who exists on the fringes of languages and shape. Armed with a knowledge of words, the right reader can uncover her true nature immediately, disarming her power. Those unknowing readers are far more likely to be caught in her jaws.

Soraya Gallant, Ryerson University, 2018

Citation: Gallant, Soraya. "Transforming the Wolf in Words, White Fell, and the Power of Names," Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Soraya Gallant, et al, COVE Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/transforming-wolf-words-white-fell-and-importance-names.

Works Cited

The Bible. Authorized King James Version, Oxford UP, 1998.

Biles, Jeremy. Ecce Monstrum: Georges Bataille and the Sacrifice of Form. New York, Fordham University Press, 2007.

Encyclopedia of Shinto, Kokugakuin University, 2007. Accessed 19 Mar 2018.

Hodges, Shari. “The Motif of the Double in Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf.” Housman Society Journal, vol. 17, 1991, pp. 57-66.

Housman, Clemence. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Laurence Housman. John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1896.

Ingebretsen, Edward. At Stake: Monsters and the Rhetoric of Fear in Public Culture. Chicago, U of Chicago P, 2001.

"Isis and the Name of Ra." University College London, 2003. Accessed 5 Mar 2018. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/literature/isisandra.html

OED Online, Oxford UUP, March 2018. Accessed 28 Feb 2018.