Scandinavian Myths and Grimm's Tales in Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf

Within the realms of mythology, culture, and religion, the wolf often represents abomination and is the personification of evil. It is a character associated with witchcraft, damnation, and even demonology. Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf transforms werewolf folklore by adapting the symbols and archetypes of werewolves from different origins. The werewolf canon is in fact riddled with variants and shifts, including the myth of Fenrir the giant wolf, Lycaon, who is cursed by Zeus and transforms into a werewolf, and Romulus and Remus, the twin brothers who are suckled and nursed by a she-wolf. There are also the Nattmara—the race of female werewolves, and the Grimm Brothers’ wolf-tales.

Nonetheless, Housman’s The Were-Wolf also attempts to shift this paradigm by introducing an archetype that challenges popular narratives surrounding wolves and lycanthrophy. Housman’s approach of using White Fell—a woman who transforms into a wolf, who kisses as a means of hunting prey, and whose beauty is so apparent that she attracts the interests of Sweyn, the protagonist—breaks away from the common narrative associated with werewolves as monstrous, terrifying beasts with purely animalistic character traits.

Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf embodies the archetype of Norse mythology names, characters, and Úlfhéðnar customs in Sigmund and Sinfjötli. It conveys the archetype of the Nattmara myth—a she-wolf who comes in the night to a family’s house and kills them while they are sleeping. The Were-Wolf is also palpable with the archetypes of a wolf requesting that a door be opened, and of children approaching strangers with caution, as seen in the Grimm Brothers’ The Wolf and The Seven Goslings and Little Red Cap (1882).

Figure 1. Bronze age engraving of a Berserker about to decapitate enemy. Sweden. Wikimedia Commons

Figure 1. Bronze age engraving of a Berserker about to decapitate enemy. Sweden. Wikimedia Commons

In northern Europe, the wolf was an animal regarded with great fear and respect. In fact, northern Europeans were well-known to imitate the wolf’s appearance when hunting in prehistoric times. The act of covering human skin with that of a wolf relates to a Scandinavian myth where people did so to trick wolves when hunting, so as to prevent themselves from becoming the wolves’ prey (Beresford 20-23). Some myths suggest that wearing animal skins relates to the possession of superpowers, as it is seen in the Norse warriors’ custom of wearing bear skins (Berserkr-bear warriors) and wolf skins (Úlfhéðnar wolf warriors) to gain access to diabolical fury and power (Baring-Gould 11).

The Völsung Saga tells the story of Sigmund and Sinfjötli, a father and son who are cursed for wearing wolf skins to cause mischief. This myth told how Sigmund and Sinfjötli were found in the cave with the wolf skins hanging on the wall above their heads. While Norse warriors used the wolf-skin as part of their armour in war, these two men used the wolf-skin for robbery and violence. Thus, they are cursed with not being able to remove the wolf-skin and begin to howl. In order to free themselves from the curse, they have to kill seven men (Baring-Gould 12; Beresford 75).

Figure 2. Christian and White Fell wearing furred clothing in "The Race," by Laurence Housman (1896)

Figure 2. Christian and White Fell wearing furred clothing in "The Race," by Laurence Housman (1896)

In Housman’s The Were-Wolf, Sweyn wears a bearskin cloak (Housman 20) like the Berserkr, while White Fell dresses like an Úlfheðinn (wolf-warrior). She comes to a farmstead as a fair beauty in fur clothes which resemble a white wolf’s skin. The use of animal skin as a disguise is a tradition seen throughout the narrative of Sigmund and Sinfjötli, and the narrative of The Wolf and The Seven Goslings where the wolf disguises himself as the goslings’ mother. Housman’s The Were-Wolf draws on this folklore, as both Christian and White Fell wear animal skins, and they race one another as if they are hunting each other. In this regard, The Were-Wolf clearly reflects the Scandinavian traditions of Berserkr and Úlfhéðnar.

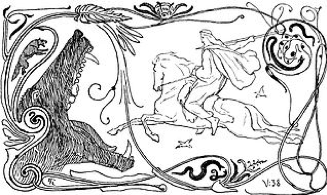

Figure 3. Odin Rides to Battle against Fenrir. Published in Gjellerup, Karl (1895). Den ældre Eddas Gudesange, p. 17. Photographed from a 2001 reprint by User:Haukurth. Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3. Odin Rides to Battle against Fenrir. Published in Gjellerup, Karl (1895). Den ældre Eddas Gudesange, p. 17. Photographed from a 2001 reprint by User:Haukurth. Wikimedia Commons

Norse mythology speaks of Fenrir, the giant wolf and son of the shapeshifter god, Loki. Fenrir is a mythical creature that continues growing into a powerful being, by whom the gods feel threatened. For that reason, Odin tries to bind him with chains (Beresford 69). This speaks to the reverence given to wolves in Norse mythology, where they were considered to be great animals who possessed divine power like Fenrir, who is believed to be the one who kills Odin in Ragnarok. Thus, many werewolf stories use names and characters from Norse mythology, emphasizing its importance in the werewolf folklore tradition.

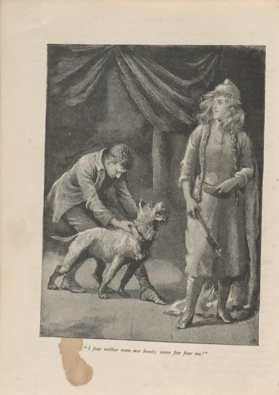

Figure 4. Christian restrains Tyr from attacking White Fell in Everard Hopkins's illustration for Atalanta (1890). Public Domain

Figure 4. Christian restrains Tyr from attacking White Fell in Everard Hopkins's illustration for Atalanta (1890). Public Domain

The Were-Wolf emulates names and characteristics of Norse gods such as Tyr, the God of war and justice who bravely puts his hand into Fenrir’s mouth and, as a result, has his arm bitten off by Fenrir (Beresford 69). In The Were-Wolf, Tyr is a dog who barks at White Fell, and howls to indicate his sense of a wolf’s presence. Tyr even leaps onto White Fell as if he wants to attack the beautiful lady. Christian also praises Tyr as a brave dog, saying “Good Tyr! Brave dog!” (Housman 35). Tyr’s courage and keen senses reflect the characteristics of Tyr, the Norse God.

The Were-Wolf further references Norse mythology through the character of Thora, whose name is the same as a mythical character in the Norse Sagas. In this tale, Thora is a beautiful lady who lives in a bower surrounded by Lindworm, a giant serpent monster. Thora is mentioned in The Were-Wolf when old Trella compares White Fell’s beauty with Thora: “So she sang, my Thora; my last and brightest. What is she like, she whose voice is like my dead Thora’s? Are her eyes blue?” (Housman 58-59).

White Fell as a she-wolf also speaks to the myth of the Nattmara, she-wolves disguised as young, slim women, dressed in nightgowns, with pale skin and long black hair and nails. They come in the night to houses and spread terror like White Fell. However, unlike White Fell who bites her prey, Nattmara torment people while they sleep by giving them nightmares and draining them of their energy. This portrayal is very similar to the Banshee creature and The Nightmare (1781) painting by Henry Fuseli. Like the Nattmara, White Fell is a female werewolf who preys upon families—she preys upon the youngest, Rol; the oldest, Trella; and the strongest, Sweyn.

Figure 5. White Fell and Rol, her first victim, as depicted by Everard Hopkins for Atalanta (1890). Public Domain

Figure 5. White Fell and Rol, her first victim, as depicted by Everard Hopkins for Atalanta (1890). Public Domain

Unlike typical Norse mythology, which often aligns stories of the wolf with themes of savagery and monstrosity, the Brothers Grimm portray the wolf as an innate trickster who disguises himself as someone familiar to his victims as a means of gaining access. This is reflected in Housman’s the Were-Wolf in the way that White Fell comes to Sweyn’s family as a human dressed in furry clothes like a hunter.

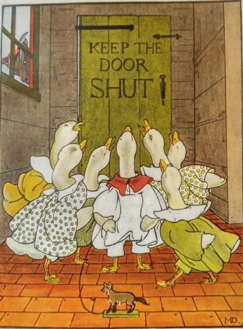

Furthermore, in the Brothers Grimm’s The Wolf and The Seven Goslings, the wolf comes to the door of the goose family with his voice disguised as a woman’s, asking for the young goslings to open the door: “Open the door, my dear children; your mother is come back, and has brought each of you something” (Grimm 40). The Were-Wolf alludes to this when Sweyn hears the faint voice of a child saying, “Open, open; Let me in!” (Housman 14).

Figure 6. Mabel Dearmer's illustration for Laurence Housman's Story of the Seven Young Goslings, 1898. Public Domain Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm also infuse a moral in their tale, as is consistent throughout many versions of Little Red Cap (also known as Little Red Riding Hood, written by Charles Perrault in the 1600s). These stories warn children not to talk to or be friendly with strangers (Beckett 15). The Were-Wolf delivers this same message through Rol, one of White Fell’s victims. Rol instantly becomes friendly with White Fell as soon as she enters the farmstead, asking her: “What is your name?” (25). He even crawls onto White Fell’s lap, causing his aunt to screech a reminder to watch his manners (see figure 5). We see Rol punished for this lack of caution when we learn that White Fell has given the little boy her kiss of death. Judging from White Fell’s victims—a child (Rol), a grandmother (Trella), and a huntsman (Christian), The Were-Wolf also seems to mimic the characters from Little Red Cap.

Figure 6. Mabel Dearmer's illustration for Laurence Housman's Story of the Seven Young Goslings, 1898. Public Domain Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm also infuse a moral in their tale, as is consistent throughout many versions of Little Red Cap (also known as Little Red Riding Hood, written by Charles Perrault in the 1600s). These stories warn children not to talk to or be friendly with strangers (Beckett 15). The Were-Wolf delivers this same message through Rol, one of White Fell’s victims. Rol instantly becomes friendly with White Fell as soon as she enters the farmstead, asking her: “What is your name?” (25). He even crawls onto White Fell’s lap, causing his aunt to screech a reminder to watch his manners (see figure 5). We see Rol punished for this lack of caution when we learn that White Fell has given the little boy her kiss of death. Judging from White Fell’s victims—a child (Rol), a grandmother (Trella), and a huntsman (Christian), The Were-Wolf also seems to mimic the characters from Little Red Cap.

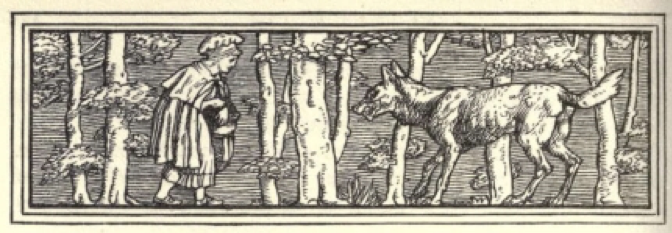

Figure 7. Walter Crane. Little Red Cap,1882, Household Stories: From the Collection of Bros. Grimm. Digital Image from Top Illustrations by Top Artists.

Figure 7. Walter Crane. Little Red Cap,1882, Household Stories: From the Collection of Bros. Grimm. Digital Image from Top Illustrations by Top Artists.

Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf is rich with folklore traditions, transforming legend into gothic novella at the end of nineteenth century. Through referencing the Scandinavian myths and the Brothers Grimm’s wolf-tales, Clemence Housman shows a she-wolf narrative is not new. In fact, it is deeply rooted in myths and folklore. The Were-Wolf is not only eloquent with the canon of Norse myths and Grimm’s tales, it also conveys symbols of the werewolf’s death kiss to mark its victims. However, this has no precedent in the Scandinavian myths or the Grimms’ tales. The Were-Wolf participates in the late-nineteenth century traditions of transformation and the uncanny to reveal the gothic genre of the nineteenth century. Clemence Housman strengthens the gothic uncanny through reworking myths of werewolf transformation and supernatural power. She mimics the renowned Brothers Grimm’s Household Tales (1882) in such a way that she insinuates the wolf tale is a trickster narrative of enticement. She revisits Little Red Cap and The Wolf and Seven Little Goslings to show that human truths are transformable (Orenstein 15).

Erni Suparti, Ryerson University, 2018

Citation: Suparti, Erni. “Scandinavian Myths and Grimm’s Tales in Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf.” Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Erni Suparti, et,al, COVE Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/scandinavian-myths-and-grimms-tales-clemence-housmans-were-wolf

Works Cited

Baring-Gould, Sabine. The Book of Were-Wolves, Blackmask Online, 2002. pp. 1-79.

Beckett, Sandra L. “Cautionary Tales for Modern Riding Hoods.” Red Riding Hood for All Ages: A Fairy Tale Icon in Cross Cultural Contexts, Wayne State UP, 2008, pp. 12-41.

Beresford, Matthew. The White Devil: The Werewolf in European Culture, Reaktion Books, 2013.

Crane, Walter. “Little Red Cap.” Household Stories, From the Collection of Bros Grimm, Macmillan & Co., 1882, page132, https://topillustrations.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/little-red-cap-head.jpg

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. Household Stories, From the Collection of Bros. Grimm, Translated by Lucy Crane, London, Macmillan & Co., 1882, pp. 40-135.

Housman, Clemence. The Were-Wolf, John Lane at The Bodley Head, 1896.

Orenstein, Catherine. Little Red Riding Hood Uncloaked: Sex, Morality, and The Evolution of a Fairy Tale, Basic Books, 2002.