THE WERE-WOLF

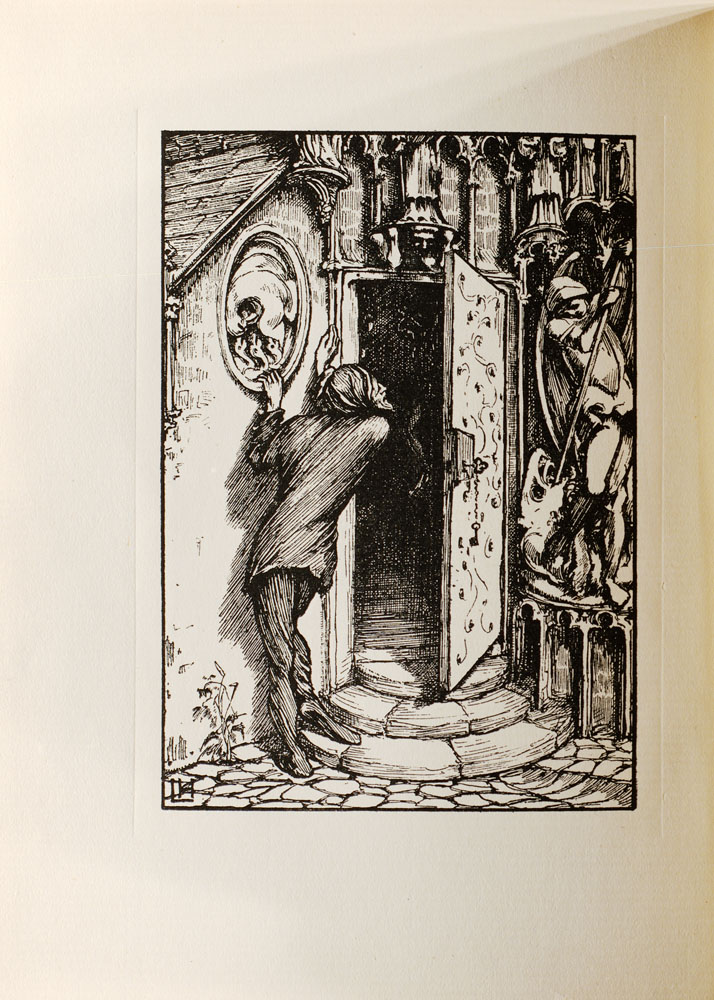

HOLY WATER

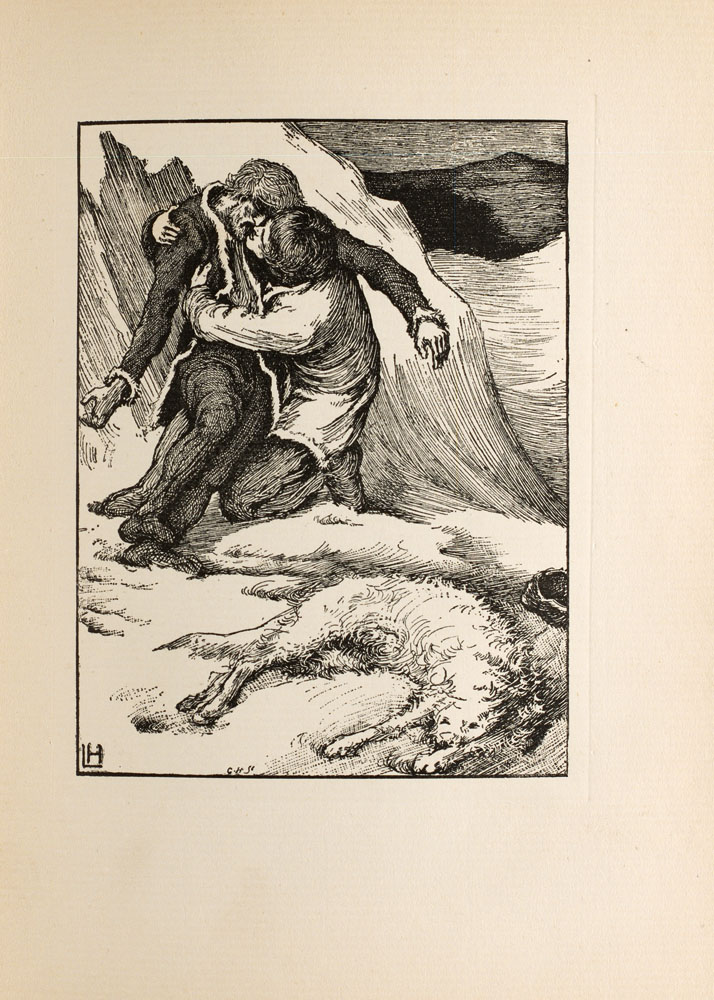

Frontispiece

̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲

̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲

̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲

TO THE DEAR MEMORY OF

E. W. P.

❧

"YOU WILL THINK OF ME SOMETIMES,

MY DEAR?"

̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲

LIST OF PLATES

HOLY WATER . . Frontispiece

ROL'S WORSHIP . . To face page 8

WHITE FELL'S ESCAPE . 60

THE RACE . . . 80

THE FINISH . . . 100

SWEYN'S FINDING . . 116

ROL'S WORSHIP . . To face page 8

WHITE FELL'S ESCAPE . 60

THE RACE . . . 80

THE FINISH . . . 100

SWEYN'S FINDING . . 116

̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲̲

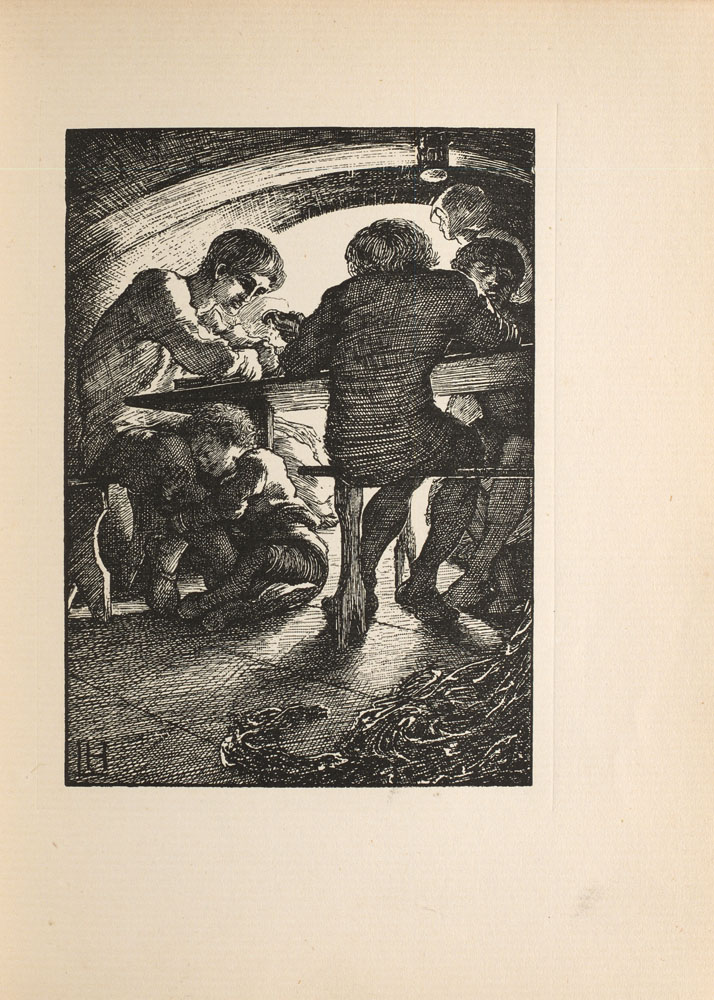

HE great farm hall was

ablaze with the fire-light, and noisy with

laughter and talk and many-sounding

work. None could be idle but the very

young and the very old: little Rol, who was

hugging a puppy, and old Trella, whose

palsied hand fumbled over her knitting.

The early evening had closed in, and

the farm-servants, come from their out-

door work, had assembled in the ample

hall, which gave space for a score or more

of workers. Several of the men were

engaged in carving, and to these were

1

yielded the best place and light; others

made or repaired fishing-tackle and

harness, and a great seine net occupied

three pairs of hands. Of the women

most were sorting and mixing eider

feather and chopping straw to add

to it. Looms were there, though not

in present use, but three wheels whirred

emulously, and the finest and swiftest

thread of the three ran between the

fingers of the house-mistress. Near her

were some children, busy too, plaiting

wicks for candles and lamps. Each

group of workers had a lamp in its

centre, and those farthest from the fire

had live heat from two braziers filled

with glowing wood embers, replenished

now and again from the generous hearth.

But the flicker of the great fire was mani-

fest to remotest corners, and prevailed

beyond the limits of the weaker lights.

Little Rol grew tired of his puppy,

dropped it incontinently, and made an

2

onslaught on Tyr, the old wolf-hound,

who basked dozing, whimpering and

twitching in his hunting dreams.

Prone went Rol beside Tyr, his young

arms round the shaggy neck, his curls

against the black jowl. Tyr gave a

perfunctory lick, and stretched with a

sleepy sigh. Rol growled and rolled

and shoved invitingly, but could only

gain from the old dog placid toleration

and a half-observant blink. "Take

that then!" said Rol, indignant at

this ignoring of his advances, and sent

the puppy sprawling against the dignity

that disdained him as playmate. The dog

took no notice, and the child wandered

off to find amusement elsewhere.

The baskets of white eider feathers

caught his eye far off in a distant corner.

He slipped under the table, and crept

along on all-fours, the ordinary common-

place custom of walking down a room

upright not being to his fancy. When

3

close to the women he lay still for a

moment watching, with his elbows on

the floor and his chin in his palms.

One of the women seeing him nodded

and smiled, and presently he crept out

behind her skirts and passed, hardly

noticed, from one to another, till he

found opportunity to possess himself of

a large handful of feathers. With these

he traversed the length of the room,

under the table again, and emerged near

the spinners. At the feet of the

youngest he curled himself round,

sheltered by her knees from the ob-

servation of the others, and disarmed her

of interference by secretly displaying his

handful with a confiding smile. A

dubious nod satisfied him, and pre-

sently he started on the play he had

devised. He took a tuft of the white

down, and gently shook it free of his

fingers close to the whirl of the wheel.

The wind of the swift motion took it,

4

spun it round and round in widening

circles, till it floated above like a slow

white moth. Little Rol's eyes danced,

and the row of his small teeth shone

in a silent laugh of delight. Another

and another of the white tufts was sent

whirling round like a winged thing in

a spider's web, and floating clear at last.

Presently the handful failed.

Rol sprawled forward to survey the

room, and contemplate another journey

under the table. His shoulder, thrusting

forward, checked the wheel for an in-

stant; he shifted hastily. The wheel

flew on with a jerk, and the thread

snapped. "Naughty Rol!" said the

girl. The swiftest wheel stopped also,

and the house-mistress, Rol's aunt, leaned

forward, and sighting the low curly head,

gave a warning against mischief, and sent

him off to old Trella's corner.

Rol obeyed, and after a discreet period

of obedience, sidled out again down the

5

length of the room farthest from his

aunt's eye. As he slipped in among the

men, they looked up to see that their

tools might be, as far as possible, out of

reach of Rol's hands, and close to their

own. Nevertheless, before long he man-

aged to secure a fine chisel and take off

its point on the leg of the table. The

carver's strong objections to this discon-

certed Rol, who for five minutes there-

after effaced himself under the table.

During this seclusion he contemplated

the many pairs of legs that surrounded

him, and almost shut out the light of

the fire. How very odd some of the

legs were: some were curved where they

should be straight, some were straight

where they should be curved, and, as

Rol said to himself, "they all seemed

screwed on differently." Some were

tucked away modestly under the benches,

others were thrust far out under the

table, encroaching on Rol's own par-

6

ticular domain. He stretched out his

own short legs and regarded them critic-

ally, and, after comparison, favourably.

Why were not all legs made like his, or

like his?

These legs approved by Rol were a

little apart from the rest. He crawled

opposite and again made comparison.

His face grew quite solemn as he thought

of the innumerable days to come before

his legs could be as long and strong. He

hoped they would be just like those, his

models, as straight as to bone, as curved

as to muscle.

A few moments later Sweyn of the

long legs felt a small hand caressing his

foot, and looking down, met the upturned

eyes of his little cousin Rol. Lying on

his back, still softly patting and stroking

the young man's foot, the child was quiet

and happy for a good while. He watched

the movement of the strong deft hands,

and the shifting of the bright tools. Now

7

and then, minute chips of wood, puffed

off by Sweyn, fell down upon his face.

At last he raised himself, very gently,

lest a jog should wake impatience in the

carver, and crossing his own legs round

Sweyn's ankle, clasping with his arms

too, laid his head against the knee. Such

act is evidence of a child's most wonder-

ful hero-worship. Quite content was

Rol, and more than content when Sweyn

paused a minute to joke, and pat his

head and pull his curls. Quiet he re-

mained, as long as quiescence is possible

to limbs young as his. Sweyn forgot he

was near, hardly noticed when his leg

was gently released, and never saw the

stealthy abstraction of one of his tools.

Ten minutes thereafter was a lament-

able wail from low on the floor, rising

to the full pitch of Rol's healthy lungs;

for his hand was gashed across, and the

copious bleeding terrified him. Then was

there soothing and comforting, washing

8

ROL'S WORSHIP

and binding, and a modicum of scolding,

till the loud outcry sank into occasional

sobs, and the child, tear-stained and sub-

dued, was returned to the chimney-corner

settle, where Trella nodded.

In the reaction after pain and fright,

Rol found that the quiet of that fire-lit

corner was to his mind. Tyr, too, dis-

dained him no longer, but, roused by his

sobs, showed all the concern and sym-

pathy that a dog can by licking and wist-

ful watching. A little shame weighed

also upon his spirits. He wished he had

not cried quite so much. He remem-

bered how once Sweyn had come home

with his arm torn down from the shoulder,

and a dead bear; and how he had never

winced nor said a word, though his lips

turned white with pain. Poor little Rol

gave another sighing sob over his own

faint-hearted shortcomings.

The light and motion of the great fire

began to tell strange stories to the child,

13

and the wind in the chimney roared a

corroborative note now and then. The

great black mouth of the chimney,

impending high over the hearth, re-

ceived as into a mysterious gulf murky

coils of smoke and brightness of aspiring

sparks; and beyond, in the high darkness,

were muttering and wailing and strange

doings, so that sometimes the smoke

rushed back in panic, and curled out and

up to the roof, and condensed itself to

invisibility among the rafters. And then

the wind would rage after its lost prey,

and rush round the house, rattling and

shrieking at window and door.

In a lull, after one such loud gust, Rol

lifted his head in surprise and listened.

A lull had also come on the babel of talk,

and thus could be heard with strange

distinctness a sound outside the door—

the sound of a child's voice, a child's

hands. "Open, open; let me in!"

piped the little voice from low down,

14

lower than the handle, and the latch

rattled as though a tiptoe child reached

up to it, and soft small knocks were

struck. One near the door sprang up and

opened it. " No one is here," he said.

Tyr lifted his head and gave utterance to

a howl, loud, prolonged, most dismal.

Sweyn, not able to believe that his

ears had deceived him, got up and went

to the door. It was a dark night; the

clouds were heavy with snow, that had

fallen fitfully when the wind lulled.

Untrodden snow lay up to the porch;

there was no sight nor sound of any

human being. Sweyn strained his eyes

far and near, only to see dark sky, pure

snow, and a line of black fir trees on a

hill brow, bowing down before the wind.

"It must have been the wind," he said,

and closed the door.

Many faces looked scared. The sound

of a child's voice had been so distinct—

and the words "Open, open; let me

15

in!" The wind might creak the wood,

or rattle the latch, but could not speak

with a child's voice, nor knock with the

soft plain blows that a plump fist gives.

And the strange unusual howl of the

wolf-hound was an omen to be feared, be

the rest what it might. Strange things

were said by one and another, till the

rebuke of the house-mistress quelled them

into far-off whispers. For a time after

there was uneasiness, constraint, and si-

lence; then the chill fear thawed by

degrees, and the babble of talk flowed on

again.

Yet half-an-hour later a very slight

noise outside the door sufficed to arrest

every hand, every tongue. Every head

was raised, every eye fixed in one direc-

tion." It is Christian; he is late," said

Sweyn.

No, no; this is a feeble shuffie, not a

young man's tread. With the sound of

uncertain feet came the hard tap-tap of

16

a stick against the door, and the high-

pitched voice of eld, "Open, open; let

me in!" Again Tyr flung up his head

in a long doleful howl.

Before the echo of the tapping stick

and the high voice had fairly died away,

Sweyn had sprung across to the door

and flung it wide. "No one again," he

said in a steady voice, though his eyes

looked startled as he stared out. He saw

the lonely expanse of snow, the clouds

swagging low, and between the two the

ine of dark fir-trees bowing in the wind.

He closed the door without a word of

comment, and re-crossed the room.

A score of blanched faces were turned

to him as though he must be solver of

the enigma. He could not be uncon-

scious of this mute eye-questioning, and

it disturbed his resolute air of composure.

He hesitated, glanced towards his mother,

the house-mistress, then back at the

frightened folk, and gravely, before them

17

all, made the sign of the cross. There

was a flutter of hands as the sign was

repeated by all, and the dead silence was

stirred as by a huge sigh, for the held

breath of many was freed as though the

sign gave magic relief.

Even the house-mistress was per-

turbed. She left her wheel and crossed

the room to her son, and spoke with

him for a moment in a low tone that

none could overhear. But a moment

later her voice was high-pitched and

loud, so that all might benefit by her

rebuke of the "heathen chatter" of one

of the girls. Perhaps she essayed to

silence thus her own misgivings and

forebodings.

No other voice dared speak now with

its natural fulness. Low tones made

intermittent murmurs, and now and

then silence drifted over the whole

room. The handling of tools was as

noiseless as might be, and suspended on

18

the instant if the door rattled in a gust

of wind. After a time Sweyn left his

work, joined the group nearest the door,

and loitered there on the pretence of

giving advice and help to the unskilful.

A man's tread was heard outside in

the porch. "Christian!" said Sweyn

and his mother simultaneously, he con-

fidently, she authoritatively, to set the

checked wheels going again. But Tyr

flung up his head with an appalling howl.

"Open, open; let me in!"

It was a man's voice, and the door

shook and rattled as a man's strength

beat against it. Sweyn could feel the

planks quivering, as on the instant his

hand was upon the door, flinging it

open, to face the blank porch, and be-

yond only snow and sky, and firs aslant

in the wind.

He stood for a long minute with the

open door in his hand. The bitter

wind swept in with its icy chill, but a

19

deadlier chill of fear came swifter, and

seemed to freeze the beating of hearts.

Sweyn stepped back to snatch up a

great bearskin cloak

"Sweyn, where are you going?"

"No farther than the porch, mother,"

and he stepped out and closed the door.

He wrapped himself in the heavy fur,

and leaning against the most sheltered

wall of the porch, steeled his nerves

to face the devil and all his works.

No sound of voices came from within;

the most distinct sound was the crackle

and roar of the fire.

It was bitterly cold. His feet grew

numb, but he forbore stamping them

into warmth lest the sound should strike

panic within ; nor would he leave the

porch, nor print a footmark on the un-

trodden white that declared so absolutely

how no human voices and hands could

have approached the door since snow

fell two hours or more ago. "When

20

the wind drops there will be more

snow," thought Sweyn.

For the best part of an hour he kept

his watch, and saw no living thing—

heard no unwonted sound. "I will

freeze here no longer," he muttered,

and re-entered.

One woman gave a half-suppressed

scream as his hand was laid on the latch,

and then a gasp of relief as he came in.

No one questioned him, only his mother

said, in a tone of forced unconcern,

"Could you not see Christian coming?"

as though she were made anxious only

by the absence of her younger son.

Hardly had Sweyn stamped near to the

fire than clear knocking was heard at the

door. Tyr leapt from the hearth, his

eyes red as the fire, his fangs showing

white in the black jowl, his neck ridged

and bristling ; and overleaping Rol,

ramped at the door, barking furiously.

Outside the door a clear mellow voice

21

was calling. Tyr's bark made the words

undistinguishable.

No one offered to stir towards the door

before Sweyn.

He stalked down the room resolutely,

lifted the latch, and swung back the door.

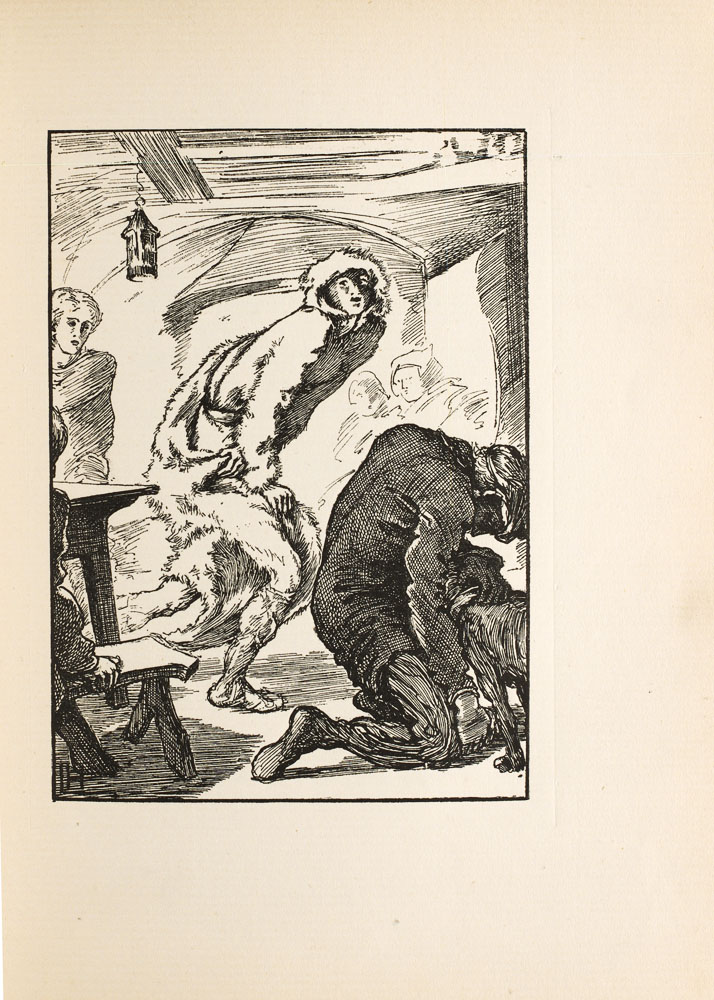

A white-robed woman glided in.

No wraith! Living—beautiful—

young.

Tyr leapt upon her.

Lithely she baulked the sharp fangs

with folds of her long fur robe, and

snatching from her girdle a small two-

edged axe, whirled it up for a blow of

defence.

Sweyn caught the dog by the collar,

and dragged him off yelling and struggling.

The stranger stood in the doorway

motionless, one foot set forward, one arm

flung up, till the house-mistress hurried

down the room; and Sweyn, relinquishing

to others the furious Tyr, turned

22

again to close the door, and offer excuse

for so fierce a greeting. Then she

lowered her arm, slung the axe in its

place at her waist, loosened the furs

about her face, and shook over her

shoulders the long white robe—all as it

were with the sway of one movement.

She was a maiden, tall and very fair.

The fashion of her dress was strange,

half masculine, yet not unwomanly. A

fine fur tunic, reaching but little below

the knee, was all the skirt she wore;

below were the cross-bound shoes and

leggings that a hunter wears. A white

fur cap was set low upon the brows, and

from its edge strips of fur fell lappet-wise

about her shoulders; two of these at her

entrance had been drawn forward and

crossed about her throat, but now,

loosened and thrust back, left unhidden

long plaits of fair hair that lay forward

on shoulder and breast,down to the ivory-

studded girdle where the axe gleamed.

23

Sweyn and his mother led the stranger

to the hearth without question or sign

of curiosity, till she voluntarily told her

tale of a long journey to distant kindred,

a promised guide unmet, and signals and

landmarks mistaken.

"Alone!" exclaimed Sweyn in astonish-

ment "Have you journeyed thus far,

a hundred leagues, alone?"

She answered "Yes" with a little smile.

"Over the hills and the wastes! Why,

the folk there are savage and wild as

beasts."

She dropped her hand upon her axe

with a laugh of some scorn.

"I fear neither man nor beast; some

few fear me." And then she told strange

tales of fierce attack and defence, and

of the bold free huntress life she had

led.

Her words came a little slowly and

deliberately, as though she spoke in a

scarce familiar tongue; now and then

24

she hesitated, and stopped in a phrase, as

though for lack of some word.

She became the centre of a group of

listeners. The interest she excited dissi-

pated, in some degree, the dread inspired

by the mysterious voices. There was

nothing ominous about this young, bright,

fair reality, though her aspect was strange.

Little Rol crept near, staring at the

stranger with all his might. Unnoticed,

he softly stroked and patted a corner of

her soft white robe that reached to the

floor in ample folds. He laid his cheek

against it caressingly, and then edged up

close to her knees.

"What is your name?" he asked.

The stranger's smile and ready answer,

as she looked down, saved Rol from the

rebuke merited by his unmannerly ques-

tion.

"My real name," she said, "would

be uncouth to your ears and tongue.

The folk of this country have given me

25

another name, and from this" (she laid

her hand on the fur robe) "they call

me 'White Fell.'"

Little Rol repeated it to himself,

stroking and patting as before. "White

Fell, White Fell."

The fair face, and soft, beautiful dress

pleased Rol. He knelt up, with his

eyes on her face and an air of uncertain

determination, like a robin's on a door-

step, and plumped his elbows into her

lap with a little gasp at his own

audacity.

"Rol!" exclaimed his aunt; but,

"Oh, let him!" said White Fell, smiling

and stroking his head; and Rol

stayed.

He advanced farther, and panting at

his own adventurousness in the face of

his aunt's authority, climbed up on to

her knees. Her welcoming arms hindered

any protest. He nestled happily,

fingering the axe head, the ivory studs

26

in her girdle, the ivory clasp at her

throat, the plaits of fair hair; rubbing

his head against the softness of her fur-

clad shoulder, with a child's full confid-

ence in the kindness of beauty.

White Fell had not uncovered her

head, only knotted the pendant fur

loosely behind her neck. Rol reached

up his hand towards it, whispering her

name to himself, "White Fell, White

Fell," then slid his arms round her neck,

and kissed her—once—twice. She

laughed delightedly, and kissed him

again.

"The child plagues you?" said

Sweyn.

"No,indeed," she answered, with an

earnestness so intense as to seem

disproportionate to the occasion.

Rol settled himself again on her lap,

and began to unwind the bandage bound

round his hand. He paused a little

when he saw where the blood had

27

soaked through; then went on till his

hand was bare and the cut displayed,

gaping and long, though only skin deep.

He held it up towards White Fell, de–

sirous of her pity and sympathy.

At sight of it, and the blood–stained

linen, she drew in her breath suddenly,

clasped Rol to her—hard, hard—till he

began to struggle. Her face was hidden

behind the boy, so that none could see

its expression. It had lighted up with

a most awful glee.

Afar, beyond the fir–grove, beyond

the low hill behind, the absent Chris–

tian was hastening his return. From

daybreak he had been afoot, carrying

notice of a bear hunt to all the

best hunters of the farms and hamlets

that lay within a radius of twelve miles.

Nevertheless, having been detained till

a late hour, he now broke into a run,

going with a long smooth stride of

28

apparent ease that fast made the miles

diminish.

He entered the midnight blackness

of the fir–grove with scarcely slackened

pace, though the path was invisible;

and passing through into the open again,

sighted the farm lying a furlong off

down the slope. Then he sprang out

freely, and almost on the instant gave

one great sideways leap, and stood still.

There in the snow was the track of a

great wolf.

His hand went to his knife, his only

weapon. He stooped, knelt down, to

bring his eyes to the level of a beast, and

peered about; his teeth set, his heart

beat a little harder than the pace of his

running insisted on. A solitary wolf,

nearly always savage and of large size, is

a formidable beast that will not hesitate

to attack a single man. This wolf–track

was the largest Christian had ever seen,

and, so far as he could judge, recently

29

made. It led from under the fir–trees

down the slope. Well for him, he

thought, was the delay that had so vexed

him before: well for him that he had not

passed through the dark fir–grove when

that danger of jaws lurked there. Going

warily, he followed the track.

It led down the slope, across a broad

ice–bound stream, along the level be–

yond, making towards the farm. A less

precise knowledge had doubted, and

guessed that here might have come

straying big Tyr or his like; but

Christian was sure, knowing better

than to mistake between footmark of

dog and wolf.

Straight on—straight on towards the

farm.

Surprised and anxious grew Christian,

that a prowling wolf should dare so

near. He drew his knife and pressed

on, more hastily, more keen–eyed. Oh

that Tyr were with him!

30

Straight on, straight on, even to the

very door, where the snow failed. His

heart seemed to give a great leap and

then stop. There the track ended.

Nothing lurked in the porch, and there

was no sign of return. The firs stood

straight against the sky, the clouds lay

low; for the wind had fallen and a few

snowflakes came drifting down. In a

horror of surprise, Christian stood dazed

a moment: then he lifted the latch and

went in. His glance took in all the old

familiar forms and faces, and with them

that of the stranger, fur–clad and beauti-

ful. The awful truth flashed upon him:

he knew what she was.

Only a few were startled by the rattle

of the latch as he entered. The room

was filled with bustle and movement, for

it was the supper hour, when all tools

were laid aside, and trestles and tables

shifted. Christian had no knowledge of

what he said and did; he moved and spoke

31

mechanically, half thinking that soon he

must wake from this horrible dream.

Sweyn and his mother supposed him to

be cold and dead–tired, and spared all

unnecessary questions. And he found

himself seated beside the hearth, opposite

that dreadful Thing that looked like a

beautiful girl; watching her every move–

ment, curdling with horror to see her

fondle the child Rol.

Sweyn stood near them both, intent

upon White Fell also; but how differ–

ently! She seemed unconscious of the

gaze of both—neither aware of the chill

dread in the eyes of Christian, nor of

Sweyn's warm admiration.

These two brothers, who were twins,

contrasted greatly, despite their striking

likeness. They were alike in regular

profile, fair brown hair, and deep blue

eyes; but Sweyn's features were perfect

as a young god's, while Christian's showed

faulty details. Thus, the line of his

32

mouth was set too straight, the eyes

shelved too deeply back, and the contour

of the face flowed in less generous curves

than Sweyn's. Their height was the

same, but Christian was too slender for

perfect proportion, while Sweyn's well–

knit frame, broad shoulders, and muscular

arms, made him pre–eminent for manly

beauty as well as for strength. As a

hunter Sweyn was without rival; as a

fisher without rival. All the country–

side acknowledged him to be the best

wrestler, rider, dancer, singer. Only in

speed could he be surpassed, and in that

only by his younger brother. All others

Sweyn could distance fairly; but Chris–

tian could outrun him easily. Ay, he

could keep pace with Sweyn's most

breathless burst, and laugh and talk the

while. Christian took little pride in his

fleetness of foot, counting a man's legs to

be the least worthy of his members. He

had no envy of his brother's athletic

33

superiority, though to several feats he had

made a moderate second. He loved as

only a twin can love–proud of all that

Sweyn did, content with all that Sweyn

was; humbly content also that his own

great love should not be so exceedingly

returned, since he knew himself to be

so far less love–worthy.

Christian dared not, in the midst of

women and children, launch the horror

that he knew into words. He waited to

consult his brother; but Sweyn did not,

or would not, notice the signal he made,

and kept his face always turned towards

White Fell. Christian drew away from

the hearth, unable to remain passive with

that dread upon him.

"Where is Tyr?" he said suddenly.

Then, catching sight of the dog in a

distant corner, "Why is he chained

there?"

"He flew at the stranger," one an–

swered.

34

Christian's eyes glowed. "Yes?" he

said, interrogatively.

"He was within an ace of having his

brain knocked out."

"Tyr ?"

"Yes; she was nimbly up with that

little axe she has at her waist. It was

well for old Tyr that his master throttled

him off."

Christian went without a word to the

corner where Tyr was chained. The

dog rose up to meet him, as piteous and

indignant as a dumb beast can be. He

stroked the black head. "Good Tyr!

brave dog!"

They knew, they only; and the

man and the dumb dog had comfort

of each other.

Christian's eyes turned again towards

White Fell: Tyr's also, and he strained

against the length of the chain. Chris–

tian's hand lay on the dog's neck, and

he felt it ridge and bristle with the

35

quivering of impotent fury. Then he

began to quiver in like manner, with a

fury born of reason, not instinct; as im-

potent morally as was Tyr physically.

Oh! the woman's form that he dare not

touch! Anything but that, and he with

Tyr would be free to kill or be killed.

Then he returned to ask fresh ques–

tions.

"How long has the stranger been

here?"

"She came about half–an–hour before

you."

Who opened the door to her?"

"Sweyn: no one else dared."

The tone of the answer was mysterious.

"Why?" queried Christian." Has

anything strange happened? Tell me."

For answer he was told in a low under–

tone of the summons at the door thrice

repeated without human agency; and of

Tyr's ominous howls; and of Sweyn's

fruitless watch outside.

36

Christian turned towards his brother

in a torment of impatience for a word

apart. The board was spread, and Sweyn

was leading White Fell to the guest's

place. This was more awful: she

would break bread with them under the

roof–tree!

He started forward, and touching

Sweyn's arm, whispered an urgent en–

treaty. Sweyn stared, and shook his head

in angry impatience.

Thereupon Christian would take no

morsel of food.

His opportunity came at last. White

Fell questioned of the landmarks of

the country, and of one Cairn Hill,

which was an appointed meeting–place

at which she was due that night.

The house–mistress and Sweyn both

exclaimed.

"It is three long miles away," said

Sweyn; "with no place for shelter but

a wretched hut. Stay with us this

37

night, and I will show you the way

to–morrow."

White Fell seemed to hesitate. "Three

miles," she said; "then I should be able

to see or hear a signal."

"I will look out," said Sweyn; "then,

if there be no signal, you must not leave

us."

He went to the door. Christian rose

silently, and followed him out.

"Sweyn, do you know what she is?"

Sweyn, surprised at the vehement

grasp, and low hoarse voice, made

answer:

"She? Who? White Fell? "

"Yes."

"She is the most beautiful girl I have

ever seen."

"She is a Were–Wolf"

Sweyn burst out laughing. "Are you

mad?" he asked.

"No; here, see for yourself."

Christian drew him out of the porch,

38

pointing to the snow where the footmarks

had been. Had been, for now they were

not. Snow was falling fast, and every

dint was blotted out.

"Well?" asked Sweyn.

"Had you come when I signed to you,

you would have seen for yourself."

"Seen what? "

"The footprints of a wolf leading up

to the door; none leading away."

It was impossible not to be startled

by the tone alone, though it was hardly

above a whisper. Sweyn eyed his brother

anxiously, but in the darkness could make

nothing of his face. Then he laid his

hands kindly and re–assuringly on Chris–

tian's shoulders and felt how he was

quivering with excitement and horror.

"One sees strange things," he said,

"when the cold has got into the brain

behind the eyes; you came in cold and

worn out."

"No," interrupted Christian. "I saw

39

the track first in the brow of the slope,

and followed it down right here to the

door. This is no delusion."

Sweyn in his heart felt positive that it

was. Christian was given to day–dreams

and strange fancies, though never had he

been possessed with so mad a notion

before.

"Don't you believe me?" said Chris-

tian desperately. "You must. I swear

it is sane truth. Are you blind? Why,

even Tyr knows."

"You will be clearer headed to–morrow

after a night's rest. Then come too, if

you will, with White Fell, to the Hill

Cairn; and if you have doubts still, watch

and follow, and see what footprints she

leaves."

Galled by Sweyn's evident contempt

Christian turned abruptly to the door.

Sweyn caught him back.

"What now, Christian? What are

you going to do?"

40

"You do not believe me; my mother

shall."

Sweyn's grasp tightened. "You shall

not tell her," he said authoritatively.

Customarily Christian was so docile to

his brother's mastery that it was now a

surprising thing when he wrenched him–

self free vigorously, and said as deter–

minedly as Sweyn, "She shall know!"

but Sweyn was nearer the door and would

not let him pass.

"There has been scare enough for one

night already. If this notion of yours

will keep, broach it to–morrow." Chris–

tian would not yield.

"Women are so easily scared," pursued

Sweyn, "and are ready to believe any folly

without shadow of proof. Be a man,

Christian, and fight this notion of a

Were–Wolf by yourself."

"If you would believe me," began

Christian.

"I believe you to be a fool," said

41

Sweyn, losing patience. "Another, who

was not your brother, might believe you

to be a knave, and guess that you had

transformed White Fell into a Were–

Wolf because she smiled more readily

on me than on you."

The jest was not without foundation,

for the grace of White Fell's bright looks

had been bestowed on him, on Christian

never a whit. Sweyn's coxcombery was

always frank, and most forgiveable, and

not without fair colour.

"If you want an ally," continued

Sweyn, "confide in old Trella. Out of

her stores of wisdom, if her memory

holds good, she can instruct you in the

orthodox manner of tackling a Were–

Wolf. If I remember aright, you should

watch the suspected person till midnight,

when the beast's form must be resumed,

and retained ever after if a human eye

sees the change; or, better still, sprinkle

hands and feet with holy water, which is

42

certain death. Oh! never fear, but old

Trella will be equal to the occasion."

Sweyn's contempt was no longer good–

humoured; some touch of irritation or

resentment rose at this monstrous doubt

of White Fell. But Christian was too

deeply distressed to take offence.

"You speak of them as old wives'

tales; but if you had seen the proof I

have seen, you would be ready at least to

wish them true, if not also to put them

to the test."

"Well," said Sweyn, with a laugh that

had a little sneer in it, "put them to

the test! I will not object to that, if you

will only keep your notions to yourself.

Now, Christian, give me your word

for silence, and we will freeze here no

longer."

Christian remained silent.

Sweyn put his hands on his shoulders

again and vainly tried to see his face in

the darkness.

43

"We have never quarrelled yet,

Christian?"

"I have never quarrelled," returned

the other, aware for the first time that his

dictatorial brother had sometimes offered

occasion for quarrel, had he been ready

to take it.

"Well," said Sweyn emphatically,

"if you speak against White Fell to any

other, as to–night you have spoken to

me—we shall."

He delivered the words like an ultim–

atum, turned sharp round, and re–entered

the house. Christian, more fearful and

wretched than before, followed.

"Snow is falling fast: not a single

light is to be seen."

White Fell's eyes passed over Christian

without apparent notice, and turned bright

and shining upon Sweyn.

"Nor any signal to be heard?" she

queried. "Did you not hear the sound

of a sea–horn?"

44

"I saw nothing, and heard nothing;

and signal or no signal, the heavy snow

would keep you here perforce."

She smiled her thanks beautifully.

And Christian's heart sank like lead

with a deadly foreboding, as he noted

what a light was kindled in Sweyn's

eyes by her smile.

That night, when all others slept,

Christian, the weariest of all, watched

outside the guest–chamber till midnight

was past. No sound, not the faintest,

could be heard. Could the old tale be

true of the midnight change? What

was on the other side of the door, a

woman or a beast? he would have given

his right hand to know. Instinctively

he laid his hand on the latch, and drew

it softly, though believing that bolts

fastened the inner side. The door yielded

to his hand; he stood on the threshold;

a keen gust of air cut at him; the win–

dow stood open; the room was empty.

45

So Christian could sleep with a some–

what lightened heart.

In the morning there was surprise and

conjecture when White Fell's absence

was discovered. Christian held his

peace. Not even to his brother did he

say how he knew that she had fled

before midnight; and Sweyn, though

evidently greatly chagrined, seemed to

disdain reference to the subject of Chris–

tian's fears.

The elder brother alone joined the

bear hunt; Christian found pretext to

stay behind. Sweyn, being out of

humour, manifested his contempt by

uttering not a single expostulation.

All that day, and for many a day after,

Christian would never go out of sight of

his home. Sweyn alone noticed how he

manœuvred for this, and was clearly

annoyed by it. White Fell's name was

never mentioned between them, though

not seldom was it heard in general talk.

46

Hardly a day passed but little Rol

asked when White Fell would come

again: pretty White Fell, who kissed

like a snowflake. And if Sweyn an–

swered, Christian would be quite sure

that the light in his eyes, kindled by

White Fell's smile, had not yet died

out.

Little Rol! Naughty, merry, fair–

haired little Rol. A day came when his

feet raced over the threshold never to

return; when his chatter and laugh

were heard no more; when tears of

anguish were wept by eyes that never

would see his bright head again: never

again, living or dead.

He was seen at dusk for the last time,

escaping from the house with his puppy,

in freakish rebellion against old Trella.

Later, when his absence had begun to

cause anxiety, his puppy crept back to

the farm, cowed, whimpering and yelp–

ing, a pitiful, dumb lump of terror,

47

without intelligence or courage to guide

the frightened search.

Rol was never found, nor any trace of

him. Where he had perished was never

known; how he had perished was known

only by an awful guess—a wild beast

had devoured him.

Christian heard the conjecture "a

wolf"; and a horrible certainty flashed

upon him that he knew what wolf it

was. He tried to declare what he knew,

but Sweyn saw him start at the words

with white face and struggling lips; and,

guessing his purpose, pulled him back,

and kept him silent, hardly, by his

imperious grip and wrathful eyes, and

one low whisper.

That Christian should retain his most

irrational suspicion against beautiful

White Fell was, to Sweyn, evidence of a

weak obstinacy of mind that would but

thrive upon expostulation and argument.

But this evident intention to direct the

48

passions of grief and anguish to a hatred

and fear of the fair stranger, such as his

own, was intolerable, and Sweyn set his

will against it. Again Christian yielded

to his brother's stronger words and will,

and against his own judgment consented

to silence.

Repentance came before the new moon,

the first of the year, was old. White

Fell came again, smiling as she entered,

as though assured of a glad and kindly

welcome; and, in truth, there was only

one who saw again her fair face and

strange white garb without pleasure.

Sweyn's face glowed with delight, while

Christian's grew pale and rigid as death.

He had given his word to keep silence;

but he had not thought that she would

dare to come again. Silence was impos-

sible, face to face with that Thing,

impossible. Irrepressibly he cried out:

"Where is Rol?"

Not a quiver disturbed White Fell's

49

face. She heard, yet remained bright

and tranquil. Sweyn's eyes flashed round

at his brother dangerously. Among the

women some tears fell at the poor child's

name; but none caught alarm from its

sudden utterance, for the thought of Rol

rose naturally. Where was little Rol,

who had nestled in the stranger's arms,

kissing her; and watched for her since;

and prattled of her daily?

Christian went out silently. One only

thing there was that he could do, and he

must not delay. His horror overmastered

any curiosity to hear White Fell's smooth

excuses and smiling apologies for her

strange and uncourteous departure; or

her easy tale of the circumstances of her

return; or to watch her bearing as she

heard the sad tale of little Rol.

The swiftest runner of the country-side

had started on his hardest race: little

less than three leagues and back, which

he reckoned to accomplish in two hours,

50

though the night was moonless and the

way rugged. He rushed against the still

cold air till it felt like a wind upon his

face. The dim homestead sank below

the ridges at his back, and fresh ridges

of snow lands rose out of the obscure

horizon-level to drive past him as the

stirless air drove, and sink away behind

into obscure level again. He took no

conscious heed of landmarks, not even

when all sign of a path was gone under

depths of snow. His will was set to

reach his goal with unexampled speed;

and thither by instinct his physical forces

bore him, without one definite thought

to guide.

And the idle brain lay passive, inert,

receiving into its vacancy restless siftings

of past sights and sounds: Rol, weeping,

laughing, playing, coiled in the arms of

that dreadful Thing: Tyr—O Tyr!—

white fangs in the black jowl: the

women who wept on the foolish puppy,

51

precious for the child's last touch:

footprints from pine wood to door:

the smiling face among furs, of such

womanly beauty—smiling—smiling:

and Sweyn's face.

"Sweyn, Sweyn, O Sweyn, my

brother!"

Sweyn's angry laugh possessed his ear

within the sound of the wind of his

speed; Sweyn's scorn assailed more quick

and keen than the biting cold at his

throat. And yet he was unimpressed

by any thought of how Sweyn's anger

and scorn would rise, if this errand

were known.

Sweyn was a sceptic. His utter dis-

belief in Christian's testimony regarding

the footprints was based upon positive

scepticism. His reason refused to bend

in accepting the possibility of the super-

natural materialised. That a living

beast could ever be other than palpably

bestial—pawed, toothed, shagged, and

52

eared as such, was to him incredible;

far more that a human presence could

be transformed from its god-like aspect,

upright, free-handed, with brows, and

speech, and laughter. The wild and

fearful legends that he had known from

childhood and then believed, he regarded

now as built upon facts distorted, over-

laid by imagination, and quickened by

superstition. Even the strange summons

at the threshold, that he himself had

vainly answered, was, after the first shock

of surprise, rationally explained by him

as malicious foolery on the part of some

clever trickster, who withheld the key

to the enigma.

To the younger brother all life was a

spiritual mystery, veiled from his clear

knowledge by the density of flesh. Since

he knew his own body to be linked

to the complex and antagonistic forces

that constitute one soul, it seemed to him

not impossibly strange that one spiritual

53

force should possess divers forms for

widely various manifestation. Nor, to

him, was it great effort to believe that

as pure water washes away all natural

foulness, so water, holy by consecration,

must needs cleanse God's world from

that supernatural evil Thing. Therefore,

faster than ever man's foot had covered

those leagues, he sped under the dark,

still night, over the waste, trackless snow-

ridges to the far-away church, where

salvation lay in the holy-water stoup at

the door. His faith was as firm as any

that wrought miracles in days past, simple

as a child's wish, strong as a man's will.

He was hardly missed during these

hours, every second of which was by him

fulfilled to its utmost extent by extremest

effort that sinews and nerves could attain.

Within the homestead the while, the

easy moments went bright with words

and looks of unwonted animation, for

the kindly, hospitable instincts of the

54

inmates were roused into cordial expres-

sion of welcome and interest by the grace

and beauty of the returned stranger.

But Sweyn was eager and earnest, with

more than a host's courteous warmth.

The impression that at her first coming

had charmed him, that had lived since

through memory, deepened now in her

actual presence. Sweyn, the matchless

among men, acknowledged in this fair

White Fell a spirit high and bold as his

own, and a frame so firm and capable

that only bulk was lacking for equal

strength. Yet the white skin was moulded

most smoothly, without such muscular

swelling as made his might evident. Such

love as his frank self-love could concede

was called forth by an ardent admiration

for this supreme stranger. More admir-

ation than love was in his passion, and

therefore he was free from a lover's hesi-

tancy and delicate reserve and doubts.

Frankly and boldly he courted her favour

55

by looks and tones, and an address that

came of natural ease, needless of skill

by practice.

Nor was she a woman to be wooed

otherwise. Tender whispers and sighs

would never gain her ear; but her eyes

would brighten and shine if she heard

of a brave feat, and her prompt hand in

sympathy fall swiftly on the axe-haft and

clasp it hard. That movement ever fired

Sweyn's admiration anew; he watched

for it, strove to elicit it, and glowed

when it came. Wonderful and beautiful

was that wrist, slender and steel-strong;

also the smooth shapely hand, that curved

so fast and firm, ready to deal instant

death.

Desiring to feel the pressure of these

hands, this bold lover schemed with

palpable directness, proposing that she

should hear how their hunting songs

were sung, with a chorus that signalled

hands to be clasped. So his splendid

56

voice gave the verses, and, as the chorus

was taken up, he claimed her hands, and,

even through the easy grip, felt, as he

desired, the strength that was latent, and

the vigour that quickened the very finger-

tips, as the song fired her, and her voice

was caught out of her by the rhythmic

swell, and rang clear on the top of the

closing surge.

Afterwards she sang alone. For con-

trast, or in the pride of swaying moods

by her voice, she chose a mournful song

that drifted along in a minor chant, sad

as a wind that dirges:

"Oh, let me go!

Around spin wreaths of snow;

The dark earth sleeps below.

Far up the plain

Moans on a voice of pain:

'Where shall my babe be lain?'

In my white breast

Lay the sweet life to rest!

Lay, where it can lie best!

'Hush! hush its cries!

Dense night is on the skies:

Two stars are in thine eyes.'

57

Come, babe, away!

But lie thou till dawn be grey,

Who must be dead by day.

This cannot last;

But, ere the sickening blast,

All sorrow shall be past;

And kings shall be

Low bending at thy knee,

Worshipping life from thee.

For men long sore

To hope of what's before,—

To leave the things of yore.

Mine, and not thine,

How deep their jewels shine!

Peace laps thy head, not mine."

Old Trella came tottering from her

corner, shaken to additional palsy by an

aroused memory. She strained her dim

eyes towards the singer, and then bent

her head, that the one ear yet sensible

to sound might avail of every note. At

the close, groping forward, she mur-

mured with the high-pitched quaver

of old age:

"So she sang, my Thora; my last and

brightest. What is she like, she whose

58

voice is like my dead Thora's? Are her

eyes blue?"

"Blue as the sky."

"So were my Thora's! Is her hair

fair, and in plaits to the waist?"

"Even so," answered White Fell her

self, and met the advancing hands with

her own, and guided them to corroborate

her words by touch.

"Like my dead Thora's,"repeated the

old woman; and then her trembling

hands rested on the fur-clad shoulders,

and she bent forward and kissed the

smooth fair face that White Fell up-

turned, nothing loth, to receive and

return the caress.

So Christian saw them as he entered.

He stood a moment. After the star-

less darkness and the icy night air, and

the fierce silent two hours' race, his

senses reeled on sudden entrance into

warmth, and light, and the cheery hum

of voices. A sudden unforeseen anguish

59

assailed him, as now first he entertained

the possibility of being overmatched by

her wiles and her daring, if at the ap-

proach of pure death she should start up

at bay transformed to a terrible beast,

and achieve a savage glut at the last.

He looked with horror and pity on the

harmless, helpless folk, so unwitting of

outrage to their comfort and security.

The dreadful Thing in their midst, that

was veiled from their knowledge by

womanly beauty, was a centre of pleasant

interest. There, before him, signally

impressive, was poor old Trella, weakest

and feeblest of all, in fond nearness. And

a moment might bring about the revela-

tion of a monstrous horror—a ghastly,

deadly danger, set loose and at bay, in a

circle of girls and women and careless

defenceless men: so hideous and terrible

a thing as might crack the brain, or

curdle the heart stone dead.

And he alone of the throng prepared!

60

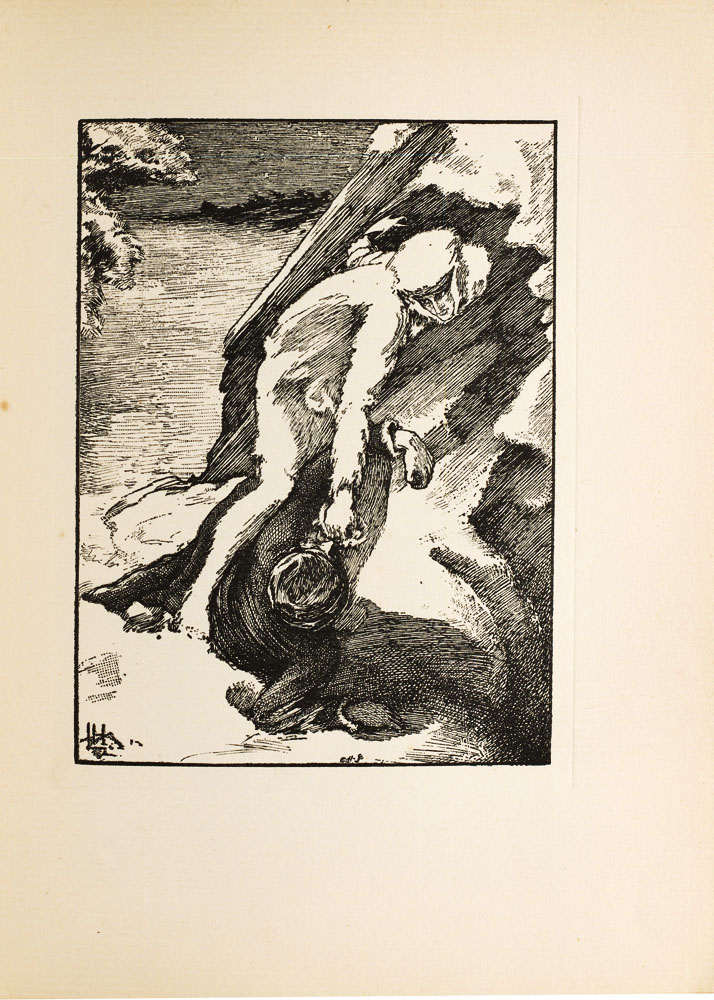

WHITE FELL'S ESCAPE

For one breathing space he faltered, no

longer than that, while over him swept

the agony of compunction that yet could

not make him surrender his purpose.

He alone? Nay, but Tyr also; and

he crossed to the dumb sole sharer of

his knowledge.

So timeless is thought that a few

seconds only lay between his lifting of

the latch and his loosening of Tyr's

collar; but in those few seconds succeed-

ing his first glance, as lightning-swift had

been the impulses of others, their motion

as quick and sure. Sweyn's vigilant eye

had darted upon him, and instantly his

every fibre was alert with hostile instinct;

and, half divining, half incredulous, of

Christian's object in stooping to Tyr, he

came hastily, wary, wrathful, resolute to

oppose the malice of his wild-eyed

brother.

But beyond Sweyn rose White Fell,

blanching white as her furs, and with

65

eyes grown fierce and wild. She leapt

down the room to the door, whirling her

long robe closely to her. "Hark!" she

panted. "The signal horn! Hark, I

must go!" as she snatched at the latch

to be out and away.

For one precious moment Christian

had hesitated on the half-loosened collar;

for, except the womanly form were ex-

changed for the bestial, Tyr's jaws would

gnash to rags his honour of manhood.

Then he heard her voice, and turned—

too late.

As she tugged at the door, he sprang

across grasping his flask, but Sweyn

dashed between, and caught him back

irresistibly, so that a most frantic effort

only availed to wrench one arm free.

With that, on the impulse of sheer

despair, he cast at her with all his force.

The door swung behind her, and the flask

flew into fragments against it. Then, as

Sweyn's grasp slackened, and he met the

66

questioning astonishment of surrounding

faces, with a hoarse inarticulate cry:

"God help us all!" he said. "She is a

Were-Wolf."

Sweyn turned upon him, "Liar, cow-

ard!" and his hands gripped his brother's

throat with deadly force, as though the

spoken word could be killed so; and as

Christian struggled, lifted him clear off

his feet and flung him crashing backward.

So furious was he, that, as his brother lay

motionless, he stirred him roughly with

his foot, till their mother came between,

crying shame; and yet then he stood by,

his teeth set, his brows knit, his hands

clenched, ready to enforce silence again

violently, as Christian rose staggering

and bewildered.

But utter silence and submission were

more than he expected, and turned his

anger into contempt for one so easily

cowed and held in subjection by mere

force. "He is mad!" he said, turning

67

on his heel as he spoke, so that he lost

his mother's look of pained reproach at

this sudden free utterance of what was a

lurking dread within her.

Christian was too spent for the effort

of speech. His hard – drawn breath

laboured in great sobs; his limbs were

powerless and unstrung in utter relax

after hard service. Failure in his en-

deavour induced a stupor of misery and

despair. In addition was the wretched

humiliation of open violence and strife

with his brother, and the distress of

hearing misjudging contempt expressed

without reserve; for he was aware that

Sweyn had turned to allay the scared

excitement half by imperious mastery,

half by explanation and argument, that

showed painful disregard of brotherly

consideration. All this unkindness of

his twin he charged upon the fell Thing

who had wrought this their first dissen-

sion, and, ah! most terrible thought,

68

interposed between them so effectually,

that Sweyn was wilfully blind and deaf

on her account, resentful of interference,

arbitrary beyond reason.

Dread and perplexity unfathomable

darkened upon him; unshared, the bur-

den was overwhelming: a foreboding of

unspeakable calamity, based upon his

ghastly discovery, bore down upon him,

crushing out hope of power to withstand

impending fate.

Sweyn the while was observant of his

brother, despite the continual check of

finding, turn and glance when he would,

Christian's eyes always upon him, with

a strange look of helpless distress, discom-

posing enough to the angry aggressor.

"Like a beaten dog!" he said to himself,

rallying contempt to withstand com-

punction. Observation set him wonder-

ing on Christian's exhausted condition.

The heavy labouring breath and the

slack inert fall of the limbs told surely

69

of unusual and prolonged exertion. And

then why had close upon two hours'

absence been followed by open hostility

against White Fell?

Suddenly, the fragments of the flask

giving a clue, he guessed all, and faced

about to stare at his brother in amaze.

He forgot that the motive scheme was

against White Fell, demanding derision

and resentment from him; that was swept

out of remembrance by astonishment

and admiration for the feat of speed and

endurance. In eagerness to question he

inclined to attempt a generous part and

frankly offer to heal the breach; but

Christian's depression and sad following

gaze provoked him to self-justification by

recalling the offence of that outrageous

utterance against White Fell; and the

impulse passed. Then other consider-

ations counselled silence; and afterwards

a humour possessed him to wait and see

how Christian would find opportunity

70

to proclaim his performance and establish

the fact, without exciting ridicule on

account of the absurdity of the errand.

This expectation remained unfulfilled.

Christian never attempted the proud

avowal that would have placed his feat

on record to be told to the next genera-

tion.

That night Sweyn and his mother

talked long and late together, shaping into

certainty the suspicion that Christian's

mind had lost its balance, and discussing

the evident cause. For Sweyn, declaring

his own love for White Fell, suggested

that his unfortunate brother, with a like

passion, they being twins in loves as in

birth, had through jealousy and despair

turned from love to hate, until reason

failed at the strain, and a craze developed,

which the malice and treachery of mad-

ness made a serious and dangerous force.

So Sweyn theorised, convincing him-

self as he spoke; convincing afterwards

71

others who advanced doubts against

White Fell; fettering his judgment by

his advocacy, and by his staunch defence

of her hurried flight silencing his own

inner consciousness of the unaccount-

ability of her action.

But a little time and Sweyn lost his

vantage in the shock of a fresh horror at

the homestead. Trella was no more, and

her end a mystery. The poor old woman

crawled out in a bright gleam to visit a

bed-ridden gossip living beyond the fir-

grove. Under the trees she was last seen,

halting for her companion, sent back for

a forgotten present. Quick alarm sprang,

calling every man to the search. Her

stick was found among the brushwood

only a few paces from the path, but no

track or stain, for a gusty wind was

sifting the snow from the branches, and

hid all sign of how she came by her

death.

So panic-stricken were the farm folk

72

that none dared go singly on the search.

Known danger could be braced, but not

this stealthy Death that walked by day

invisible, that cut off alike the child in

his play and the aged woman so near to

her quiet grave.

"Rol she kissed; Trella she kissed!"

So rang Christian's frantic cry again and

again, till Sweyn dragged him away and

strove to keep him apart, albeit in his

agony of grief and remorse he accused

himself wildly as answerable for the

tragedy, and gave clear proof that the

charge of madness was well founded, if

strange looks and desperate, incoherent

words were evidence enough.

But thenceforward all Sweyn's reason-

ing and mastery could not uphold White

Fell above suspicion. He was not called

upon to defend her from accusation when

Christian had been brought to silence

again; but he well knew the significance

of this fact, that her name, formerly

73

uttered freely and often, he never heard

now: it was huddled away into whispers

that he could not catch.

The passing of time did not sweep

away the superstitious fears that Sweyn

despised. He was angry and anxious;

eager that White Fell should return, and,

merely by her bright gracious presence,

reinstate herself in favour; but doubtful

if all his authority and example could

keep from her notice an altered aspect of

welcome; and he foresaw clearly that

Christian would prove unmanageable,

and might be capable of some dangerous

outbreak.

For a time the twins' variance was

marked, on Sweyn's part by an air of

rigid indifference, on Christian's by

heavy downcast silence, and a nervous

apprehensive observation of his brother.

Superadded to his remorse and forebod-

ing, Sweyn's displeasure weighed upon

him intolerably, and the remembrance of

74

their violent rupture was a ceaseless

misery. The elder brother, self-sufficient

and insensitive, could little know how

deeply his unkindness stabbed. A depth

and force of affection such as Christian's

was unknown to him. The loyal sub-

servience that he could not appreciate

had encouraged him to domineer; this

strenuous opposition to his reason and

will was accounted as furious malice, if

not sheer insanity.

Christian's surveillance galled him in-

cessantly, and embarrassment and danger

he foresaw as the outcome. There-

fore, that suspicion might be lulled,

he judged it wise to make overtures for

peace. Most easily done. A little kind-

liness, a few evidences of consideration,

a slight return of the old brotherly im-

periousness, and Christian replied by a

gratefulness and relief that might have

touched him had he understood all, but

instead, increased his secret contempt.

75

So successful was this finesse, that when,

late on a day, a message summoning

Christian to a distance was transmitted

by Sweyn, no doubt of its genuineness

occurred. When, his errand proved use-

less, he set out to return, mistake or

misapprehension was all that he surmised.

Not till he sighted the homestead, lying

low between the night-grey snow ridges,

did vivid recollection of the time when

he had tracked that horror to the door

rouse an intense dread, and with it a

hardly-defined suspicion.

His grasp tightened on the bear-spear

that he carried as a staff; every sense

was alert, every muscle strung; excite-

ment urged him on, caution checked

him, and the two governed his long

stride, swiftly, noiselessly, to the climax

he felt was at hand.

As he drew near to the outer gates,

a light shadow stirred and went, as

though the grey of the snow had

76

taken detached motion. A darker

shadow stayed and faced Christian,

striking his life-blood chill with ut-

most despair.

Sweyn stood before him, and surely,

the shadow that went was White Fell.

They had been together — close. Had

she not been in his arms, near enough

for lips to meet?

There was no moon, but the stars gave

light enough to show that Sweyn's face

was flushed and elate. The flush re-

mained, though the expression changed

quickly at sight of his brother. How,

if Christian had seen all, should one of

his frenzied outbursts be met and man-

aged: by resolution? by indifference?

He halted between the two, and as a

result, he swaggered.

"White Fell?" questioned Christian,

hoarse and breathless.

"Yes?"

Sweyn's answer was a query, with an

77

intonation that implied he was clearing

the ground for action.

From Christian came: "Have you

kissed her?" like a bolt direct, stagger-

ing Sweyn by its sheer prompt temerity.

He flushed yet darker, and yet half-

smiled over this earnest of success he had

won. Had there been really between

himself and Christian the rivalry that he

imagined, his face had enough of the

insolence of triumph to exasperate jealous

rage.

"You dare ask this!"

"Sweyn, O Sweyn, I must know!

You have!"

The ring of despair and anguish in his

tone angered Sweyn, misconstruing it.

Jealousy urging to such presumption was

intolerable.

"Mad fool!" he said, constraining

himself no longer. "Win for yourself

a woman to kiss. Leave mine without

question. Such an one as I should desire

78

to kiss is such an one as shall never allow

a kiss to you."

Then Christian fully understood his

supposition.

"I—I!" he cried. "White Fell—

that deadly Thing! Sweyn, are you

blind, mad? I would save you from

her: a Were-Wolf!"

Sweyn maddened again at the accusa-

tion—a dastardly way of revenge, as he

conceived; and instantly, for the second

time, the brothers were at strife violently.

But Christian was now too desperate

to be scrupulous; for a dim glimpse had

shot a possibility into his mind, and to

be free to follow it the striking of his

brother was a necessity. Thank God!

he was armed, and so Sweyn's equal.

Facing his assailant with the bear-

spear, he struck up his arms, and with

the butt end hit hard so that he fell.

The matchless runner leapt away on the

instant, to follow a forlorn hope.

79

Sweyn, on regaining his feet, was as

amazed as angry at this unaccountable

flight. He knew in his heart that his

brother was no coward, and that it was

unlike him to shrink from an encounter

because defeat was certain, and cruel

humiliation from a vindictive victor

probable. Of the uselessness of pursuit

he was well aware: he must abide his

chagrin, content to know that his time

for advantage would come. Since White

Fell had parted to the right, Christian to

the left, the event of a sequent encounter

did not occur to him.

And now Christian, acting on the dim

glimpse he had had, just as Sweyn turned

upon him, of something that moved

against the sky along the ridge behind

the homestead, was staking his only hope

on a chance, and his own superlative

speed. If what he saw was really White

Fell, he guessed she was bending her

steps towards the open wastes; and there

80

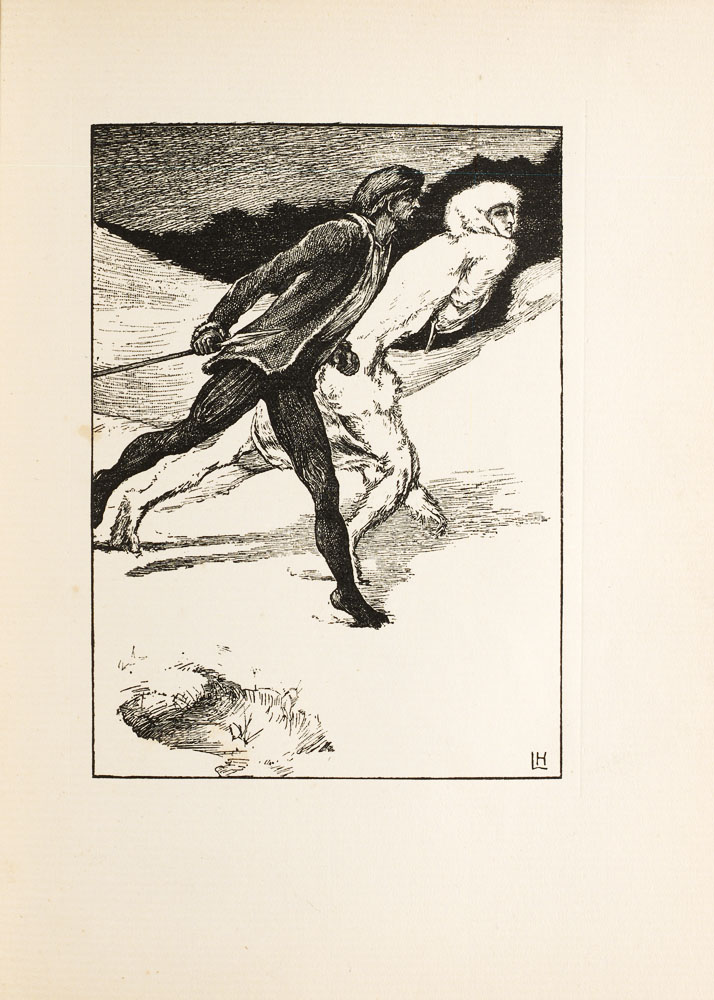

THE RACE

was just a possibility that, by a straight

dash, and a desperate perilous leap over

a sheer bluff, he might yet meet her or

head her. And then: he had no further

thought.

It was past, the quick, fierce race, and

the chance of death at the leap; and he

halted in a hollow to fetch his breath and

to look: did she come? had she gone?

She came.

She came with a smooth, gliding,

noiseless speed, that was neither walking

nor running; her arms were folded in

her furs that were drawn tight about her

body; the white lappets from her head

were wrapped and knotted closely be-

neath her face; her eyes were set on a

far distance. So she went till the even

sway of her going was startled to a pause

by Christian.

"Fell!"

She drew a quick, sharp breath at the

sound of her name thus mutilated, and

85

faced Sweyn's brother. Her eyes glit-

tered; her upper lip was lifted, and

shewed the teeth. The half of her

name, impressed with an ominous sense

as uttered by him, warned her of the

aspect of a deadly foe. Yet she cast loose

her robes till they trailed ample, and

spoke as a mild woman.

"What would you?"

Then Christian answered with his

solemn dreadful accusation:

"You kissed Rol—and Rol is dead!

You kissed Trella: she is dead! You

have kissed Sweyn, my brother; but he

shall not die!"

He added: "You may live till mid-

night."

The edge of the teeth and the glitter

of the eyes stayed a moment, and her

right hand also slid down to the axe haft.

Then, without a word, she swerved from

him, and sprang out and away swiftly

over the snow.

86

And Christian sprang out and away,

and followed her swiftly over the snow,

keeping behind, but half-a-stride's length

from her side.

So they went running together, silent,

towards the vast wastes of snow, where

no living thing but they two moved

under the stars of night.

Never before had Christian so rejoiced

in his powers. The gift of speed, and

the training of use and endurance were

priceless to him now. Though midnight

was hours away, he was confident that, go

where that Fell Thing would, hasten as

she would, she could not outstrip him nor

escape from him. Then, when came the

time fortransformation, when the woman's

form made no longer a shield against a

man's hand, he could slay or be slain to

save Sweyn. He had struck his dear

brother in dire extremity, but he could

not, though reason urged, strike a woman.

For one mile, for two miles they ran:

87

White Fell ever foremost, Christian ever

at equal distance from her side, so near

that, now and again, her out–flying furs

touched him. She spoke no word; nor

he. She never turned her head to look

at him, nor swerved to evade him; but,

with set face looking forward, sped

straight on, over rough, over smooth,

aware of his nearness by the regular

beat of his feet, and the sound of his

breath behind.

In a while she quickened her pace.

From the first, Christian had judged of

her speed as admirable, yet with exulting

security in his own excelling and endur–

ing whatever her efforts. But, when the

pace increased, he found himself put to

the test as never had he been before in

any race. Her feet, indeed, fiew faster

than his; it was only by his length of

stride that he kept his place at her side.

But his heart was high and resolute, and

he did not fear failure yet.

88

So the desperate race flew on. Their

feet struck up the powdery snow, their

breath smoked into the sharp clear air,

and they were gone before the air was

cleared of snow and vapour. Now and

then Christian glanced up to judge, by

the rising of the stars, of the coming of

midnight. So long—so long!

White Fell held on without slack.

She, it was evident, with confidence in

her speed proving matchless, as resolute

to outrun her pursuer as he to endure

till midnight and fulfil his purpose. And

Christian held on, still self–assured. He

could not fail; he would not fail. To

avenge Rol and Trella was motive enough

for him to do what man could do; but

for Sweyn more. She had kissed Sweyn,

but he should not die too: with Sweyn

to save he could not fail.

Never before was such a race as this;

no, not when in old Greece man and

maid raced together with two fates at

89

stake; for the hard running was sustained

unabated, while star after star rose and

went wheeling up towards midnight, for

one hour, for two hours.

Then Christian saw and heard what

shot him through with fear. Where a

fringe of trees hung round a slope he

saw something dark moving, and heard

a yelp, followed by a full horrid cry, and

the dark spread out upon the snow, a

pack of wolves in pursuit.

Of the beasts alone he had little cause

for fear; at the pace he held he could

distance them, four–footed though they

were. But of White Fell's wiles he had

infinite apprehension, for how might she

not avail herself of the savage jaws of

these wolves, akin as they were to half

her nature. She vouchsafed to them nor

look nor sign; but Christian, on an im–

pulse to assure himself that she should

not escape him, caught and held the

back–flung edge of her furs, running still.

90

She turned like a flash with a beastly

snarl, teeth and eyes gleaming again.

Her axe shone, on the upstroke, on the

downstroke, as she hacked at his hand.

She had lopped it off at the wrist, but

that he parried with the bear–spear. Even

then, she shore through the shaft and

shattered the bones of the hand at the

same blow, so that he loosed perforce.

Then again they raced on as before,

Christian not losing a pace, though his

left hand swung useless, bleeding and

broken.

The snarl, indubitable, though modi–

fied from a woman's organs, the vicious

fury revealed in teeth and eyes, the

sharp arrogant pain of her maiming blow,

caught away Christian's heed of the beasts

behind, by striking into him close vivid

realisation of the infinitely greater danger

that ran before him in that deadly Thing.

When he bethought him to look be–

hind, lo! the pack had but reached their

91

tracks, and instantly slunk aside, cowed;

the yell of pursuit changing to yelps

and whines. So abhorrent was that fell

creature to beast as to man.

She had drawn her furs more closely

to her, disposing them so that, instead of

flying loose to her heels, no drapery hung

lower than her knees, and this without

a check to her wonderful speed, nor

embarrassment by the cumbering of

the folds. She held her head as before;

her lips were firmly set, only the tense

nostrils gave her breath; not a sign of

distress witnessed to the long sustaining

of that terrible speed.

But on Christian by now the strain

was telling palpably. His head weighed

heavy, and his breath came labouring in

great sobs; the bear spear would have

been a burden now. His heart was

beating like a hammer, but such a dul–

ness oppressed his brain, that it was only

by degrees he could realise his helpless

92

state; wounded and weaponless, chasing

that terrible Thing, that was a fierce,

desperate, axe–armed woman, except she

should assume the beast with fangs yet

more formidable.

And still the far slow stars went linger–

ing nearly an hour from midnight.

So far was his brain astray that an

impression took him that she was fleeing

from the midnight stars, whose gain was