The Double in Gothic Fiction

Following in the literary footsteps of other gothic fiction writers, Clemence Housman uses the motif of the gothic twin or double in The Were-Wolf via its twin characters Christian and Sweyn. The gothic double has been a mainstay in gothic literature from as early as Charles Brockden Brown’s Edgar Huntly (1800), and has subsequently been reimagined in a multitude of fictional gothic texts—particularly British-authored gothic texts—such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), Edgar Allan Poe’s William Wilson (1839), Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847), and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), all of which precede the first publication of Housman’s novella in 1890.

In her comprehensive analysis of the motif of the double in The Were-Wolf, Shari Hodges argues that Housman “uses Gothic literary conventions to present a Christian allegory of the conflict between good and evil forces within the universe and within the soul of man” (57). However, Hodges’ analysis focuses principally on the religious rather than the psychological and she does not emphasize the significance of Housman’s main characters, Sweyn and Christian, as biological twins. This essay examines Housman’s reinvention of the double motif in The Were-Wolf by focusing on the narrative’s twin brothers in relation to gothic theory.

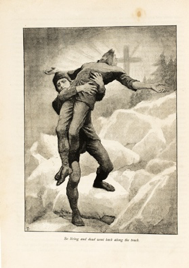

Figure 1. Everard Hopkins's illustration of Sweyn and Christian for Atalanta in 1890, highlighting the religious allegory of The Were-Wolf

Figure 1. Everard Hopkins's illustration of Sweyn and Christian for Atalanta in 1890, highlighting the religious allegory of The Were-Wolf

The terms “double” and “doppelgänger” are often used interchangeably in gothic scholarship, as there is no formal definition for the gothic double; though it can be generally understood as a physical representation of the division of the self, with two figures representing opposing sides of a good-evil dichotomy. Within the gothic narrative Housman presents, Christian would represent the “good” or Christ-like figure, and Sweyn would represent the so-called “evil” figure. Similarly, the gothic doppelgänger (German for “double-goer”) is defined as “the alter ego or identical double of a protagonist who seems to be either a victim of an identity theft perpetrated by a mimicking supernatural presence or subject to a paranoid hallucination; the split personality or dark half of the protagonist, an unleashed monster that acts as a physical manifestation of a dissociated part of the self” (“Glossary of the Gothic”). In The Were-Wolf, Christian and Sweyn represent the duality of the self by acting as two extremes—good and evil—which often present a moral conflict within a single human character in a given gothic text. The central premise of the double motif is “the paradox of encountering oneself as another; the logically impossible notion that the ‘I’ and the ‘not-I’ are somehow identical” (“Glossary of the Gothic”).

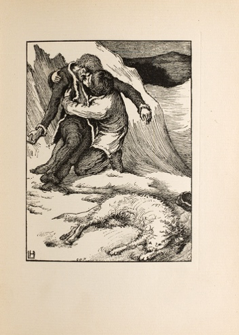

Figure 2. Laurence Housman's illustration of Sweyn and Christian as mirror images of each other for The Were-Wolf in 1896. Engraved by Clemence Housman.

Figure 2. Laurence Housman's illustration of Sweyn and Christian as mirror images of each other for The Were-Wolf in 1896. Engraved by Clemence Housman.

Based on its origins within the tradition of the German Schauerroman (German for “shudder novel”), and later the British Gothic novel, the doppelgänger, like the vampire, was a product of an early nineteenth-century fascination with folklore. Drawing from the superstitious belief that an encounter with one’s double is an omen of death, the doppelgänger motif combines a sense of supernatural horror with a philosophical inquiry concerning personal identity, along with a psychological inquiry into the concealed and complicated depths of the human psyche. Andrew Smith asserts that gothic fiction’s use of doubling is a clear manifestation of humankind’s tendency toward the internalization of “evil,” though in the late nineteenth-century (and largely secularized) Gothic tradition, the word “inner” would be more appropriate to describe these narratives, which began to involve more of the psychological and social rather than the theological (Smith 94).

In his essay "The ‘Uncanny’” (1919), Sigmund Freud initially interpreted the double as an indicator of the emergence of the adult conscience. However, Freud believed that this conscience, which has a positive role in regulating behaviour, turns into a harmfully powerful form of self-censorship that stifles the development of the self so that the double becomes “the ghastly harbinger of death” because it psychologically kills (i.e. represses) the self (9). This version of the double as a harbinger of death, as a liberator from censorship, and as a mode of repression can be observed in Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872), as well as Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886).

Alternatively, in Julia Kristeva’s essay “Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection,” there is a shift away from Freud’s ideas regarding doubling, and towards a theory which suggests that doubling in literature occurs when a culture requires that any experiences or ways of life which deviate from or threaten the status quo (i.e., crime or homosexuality in the Victorian period) be represented as wrong or “abject” (4). This explains the insistence of several gothic fiction authors to present characteristics such as physical ugliness and monstrosity as inherently wrong and punishable.

Given the presupposition that doppelgänger narratives tend to involve a duality of the protagonist who is either duplicated in the figure of an identical second self or divided into polar opposite selves, The Were-Wolf’s Christian can be interpreted as divided into two selves: himself and his twin, Sweyn. In other words, using the motif of the doppelgänger as a way of deriving meaning from Housman’s writing of the twins as physically and biologically similar yet fundamentally different, Sweyn could be seen as Christian’s alter ego.

In Housman’s novella and in gothic fiction overall, the motif of the double benefits the genre by generating the sense of the uncanny throughout the narrative. In the “Glossary of the Gothic,” David B. Morris draws from Freud’s writings on the uncanny to explain its meaning so that it can be better understood in the unique context of gothic fiction: “For Freud, the uncanny derives its terror not from something external, alien, or unknown but—on the contrary—from something strangely familiar which defeats our efforts to separate ourselves from it; we find things to be uncanny (unheimlich) when they are familiar to us (heimlich or “belonging to the home”) yet also somehow foreign or disturbing” (1).

In The Were-Wolf, this sense of the uncanny, which is typical of the gothic genre of fiction, is achieved by juxtaposing a double who resembles the protagonist yet differs from him greatly personality-wise. In reading the following passage from Housman’s text, it becomes clear that part of the narrative’s classification as a gothic text relies upon the simultaneous likeness and difference between the twin brothers:

These two brothers, who were twins, contrasted greatly, despite their striking likeness. They were alike in regular profile, fair brown hair, and deep blue eyes; but Sweyn's features were perfect as a young god's, while Christian's showed faulty details. Thus, the line of his mouth was set too straight, the eyes shelved too deeply back, and the contour of the face flowed in less generous curves than Sweyn's. Their height was the same, but Christian was too slender for perfect proportion, while Sweyn's well-knit frame, broad shoulders, and muscular arms, made him pre-eminent for manly beauty as well as for strength. (32)

This description of the two creates tension and disturbance for the reader as the familiar expectation that twins are supposed to be extremely similar is destroyed, and the right/wrong, or rather perfect/imperfect dichotomy is formed, if only in terms of appearance. Part of the rationale for reading gothic literature lies within the text’s inherent promise to thrill, terrify, and unsettle the reader, and Housman delivers this promise, in part by the use of uncanny gothic doubling in Christian and Sweyn.

Alex Heath, Ryerson University, 2018

Citation: Heath, Alex. “The Double in Gothic Fiction.” Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Alexandra Heath, et al, COVE Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/double-gothic-fict...

Works Cited

“Doppelgänger.” Oxford English Dictionary. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/doppelganger.

Freud, Sigmund. “The ‘Uncanny’.” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works, pp. 9-42.

“Glossary of the Gothic: Doppelgänger.” ePublications @ Marquette: Digital Commons by bepress. https://epublications.marquette.edu/gothic_doppelganger/.

“Glossary of the Gothic: Uncanny”. ePublications @ Marquette: Digital Commons by bepress. https://epublications.marquette.edu/gothic_uncanny/.

Hodges, Shari. “The Motif of the Double in Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf. Housman Society Journal, vol. 17, 1991, pp. 57-66.

Housman, Clemence. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Everard Hopkins, Atalanta, vol 4, no. 39, Dec. 1890, pp. 132-156.

---. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Laurence Housman, John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1896.

Kristeva, Julia. “Approaching Abjection.” Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Columbia UP, 1982, pp. 1-31.

“Schauerroman.” Oxford Reference, 2018. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.201108031004451...

Smith, Andrew. Gothic Literature, Edinburgh University Press, 2013, https://ebookcentral-proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/lib/ryerson/rea....