Clemence Housman and Feminism in the 1890s

Clemence Housman's Works

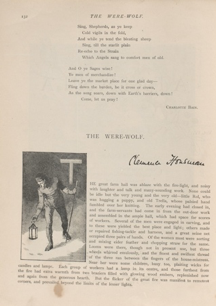

In 1896, Clemence Housman published her first book, The Were-Wolf, which had earlier appeared in the girls' monthly magazine Atalanta in 1890. The 1890s were a time when individuals, such as those called the New Women, began launching attacks on the patriarchy. Clemence and her brother Laurence took an active part in this resistance. Clemence not only advocated for women’s rights, she also marked her career with feminist elements, as can be seen in her fiction, her choice of publisher, and her decision to pursue a career in wood engraving. Clemence’s novels, such as The Were-Wolf and The Unknown Sea (1898) include intricate symbolism and allegories that Elizabeth Oakley states are “as meticulously crafted as her engravings” (50). This symbolism includes the strong feminist portrayal of seemingly monstrous women in her fiction. As Melissa Purdue suggests, Housman’s hybrid heroines act as “cautionary tales” for the progressive New Women of her day (43).

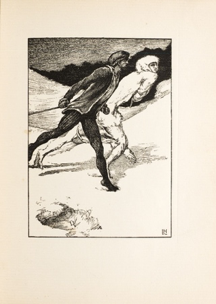

Figure 1. Laurence Housman, "The Race," engraved by Clemence Housman, showing the androgyny of White Fell and Christian (1896)

Figure 1. Laurence Housman, "The Race," engraved by Clemence Housman, showing the androgyny of White Fell and Christian (1896)

Her brother Laurence Housman’s illustrations for The Were-Wolf highlight the androgynous figure of White Fell, the work's antagonist and titled female lead, and the feminized build of Christian, the story's Christ-like protagonist. While maintaining a religious allegory of Christian’s sacrifice to save his brother Sweyn, a strong political message also lies beneath this reading. Clemence masked the modern struggles of the New Woman in works such as Strange Women, which Laurence referred to as “modern problems in an old dress” (qtd. in Oakley 52). The fact that publishers were hesitant to publicize her scandalous representations of the New Woman suggests Clemence’s radical agenda (Oakley 53). As Elizabeth Oakley states, “White Fell seems to embody the neurotic fear of the New Woman and her depraved sexual appetite” (53).

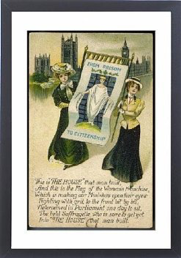

Clemence Housman’s second novel, The Unknown Sea, once again features a female lead, but Diadyomene is more complex than White Fell. Diadyomene is both the evil seductress and the victim of magic, with even her hybrid name encompassing the identity of Venus, representing beauty and sexual desire (Oakley 54). Diadyomene’s duality may allude to Housman’s own complexities—while being politically active in the feminist movement, her Christian beliefs muted her outlook on sexuality. On the other hand, one of Laurence Housman’s main inspirations in the 1890s was Edward Carpenter, who made many advancements in the homosexual community with essays such as “Love’s Coming of Age: A Series of Papers on the Relations between the Sexes.” Carpenter advocated for latitude in masculine and feminine sexuality, contributing to the women’s suffrage movement and pushing for a break in gender binary stereotypes (Oakley 43). Carpenter argued that men and women who do not identify as gender-binary often end up relying on one another, and Oakley suggests that Carpenter’s theory connected Laurence strongly to his sister Clemence (43). Laurence publicly declared himself a feminist and followed in Clemence’s footsteps by publishing his own fairy tales, for which she engraved his illustrations: The Field of Clover (1898) and The Blue Moon (1904) (Kooistra 21). After 1904, their collaborations were dedicated to women’s suffrage (Kooistra 21).

Figure 2. Postcard featuring the "From Prisonhood to Citizenship" banner made by Clemence Housman after Laurence Housman's design at their Suffrage Atelier. Public Domain

Figure 2. Postcard featuring the "From Prisonhood to Citizenship" banner made by Clemence Housman after Laurence Housman's design at their Suffrage Atelier. Public Domain

Wood Engraving: A Career for Women

Facsimile wood engraving was a popular form of printing illustrations for magazines and newspapers from the 1840s to the1890s (Kooistra 3). Although men dominated the industry, women were seen as ideal engravers due to their slight hands and the fact that their work could be done in private. The industry helped shape the interests, activities, and even the identities of women, and refashioned the ideas of gender in other discourses (Kooistra 6). Wood engraving gave women the chance to pursue alternative careers and play an integral part in the publishing industry. In an essay written in 1887 for a pamphlet entitled Occupations for Women Other than Teaching, Clemence advocated for women’s careers in wood engraving. She also noted that it was a life-long career due to the intensive training and was not for those who were looking for a couple of years of work (Kooistra 14).

Figure 3. Occupations for Women Other than Teaching. Pamphlet in Mark Samuels Lasner's Collection at University of Delaware Library containing Clemence Housman's essay on Wood Engraving as an Occupation for Women (1887)

Figure 3. Occupations for Women Other than Teaching. Pamphlet in Mark Samuels Lasner's Collection at University of Delaware Library containing Clemence Housman's essay on Wood Engraving as an Occupation for Women (1887)

Clemence became one of the most skilled engravers of her time; she was hired with only two years of training, as opposed to male apprentices who had five to seven years of training (Kooistra 13). The process of engraving was undergoing a major transition period during the 1890s with the emergence of photomechanically reproduced pictures. As Lorraine Janzen Kooistra mentions, such pictures led to the swift disappearance of the formerly large wood-engraving trade (16). Clemence, however, was able to hold on to her career because of the connections she had to her brother’s networks, as well as her own natural talent (Kooistra 11). Wood engraving gave women the chance to pursue not only new careers, but also completely new lifestyles that broke gender stereotypes in the Victorian era. It was a career that provided purpose for women whose ambitions lay beyond the domestic sphere. Clemence laid that path very clearly, and was a keen exemplar of one of the many forms of independence a woman’s life could take.

Atalanta: More than a Magazine for Girls

Clemence Housman’s feminism is evident in her selection of a magazine in which to publish The Were-Wolf (Purdue 44). Atalanta, the magazine in which The Were-Wolf was initially published in 1890, was established in 1887 as a progressive periodical focused on women, with the well-known L.T. Meade as its female editor. Meade’s fame as an author aided the magazine’s popularity and high quality literary content (Dawson 477). As the editor, Meade was able to gather famous male and female authors to contribute to the magazine. Atalanta was competing against other popular periodicals—such as the Cornhill, whose audience was university-educated men—with essays on politics, religion, economics, and culture (Dawson 477).

Figure 4. Cover for Atalanta showing inset illustration of the mythic figure stooping to pick up an apple.

Figure 4. Cover for Atalanta showing inset illustration of the mythic figure stooping to pick up an apple.

Under Meade’s editorial lead, writers for the Cornhill were also starting to write pieces for Atalanta. Atalanta continued to showcase the participation of women in intellectual, cultural, and social conversations (Dawson 481). In this light, Atalanta stood out from many other magazines for girls. Even the titular namesake, Atalanta, the Greek warrior woman displayed on the magazine's cover, was a stark contrast to the dainty maidens that appeared on the covers of other girls’ magazines (Dawson 481). Housman makes a strategic allusion to the magazine’s eponymous heroine when she describes the race across the snowy wastes by White Fell and Christian: “Never before was such a race as this; no, not when in old Greece man and maid raced together with two fates at stake” (89-90). Atalanta, under Meade’s editorial guidance, not only created writing opportunities for female writers, but also promoted the achievements of female professionals in inspirational essays. According to Janis Dawson, “Atalanta offered rigorous literary competitions, scholarships, and fiction-writing tutorials as well as articles providing current information on educational opportunities, professional development, and employment” (481).

Figure 5. First page of The Were-Wolf in Atalanta, showing Clemence Housman's authorial signature

Figure 5. First page of The Were-Wolf in Atalanta, showing Clemence Housman's authorial signature

Atalanta provided a plethora of opportunities for women and encouraged them in their professional pursuits. It seems only fitting that The Were-Wolf would make its debut in such a magazine. Clemence’s own political views seem to be embodied in Atalanta and highlight the feminist advances of the 1890s, foreshadowing the upcoming progression of the women’s suffrage movement in the United Kingdom.

Danielle DiFruscia, Ryerson University, 2018

Citation: DiFruscia, Danielle. "Clemence Housman and Feminism in the 1890s," Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Danielle DiFruscia, et al, COVE Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/clemence-housman-and-feminism-1890s.

Works Cited

Dawson, Janis. “‘Not for girls alone, but for anyone who can relish really good literature’: L.T. Meade, Atalanta, and the Family Literary Magazine.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 46, no. 4, 2013, pp. 475-98.

Housman, Clemence. The Unknown Sea. Duckworth, 1898.

---. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Everard Hopkins. Atalanta, vol 4, no. 39, Dec. 1890, pp. 132-156.

---. The Were-Wolf. With 6 illustrations by Laurence Housman engraved by Clemence Housman. John Lane Bodley Head, 1896.

[Housman, Clemence]. “Wood Engraving.” Occupations for Women Other Than Teaching. London: Association for Assistant-Mistresses, 1887, pp. 3-5. Pamphlet in Mark Samuels Lasner’s Laurence Housman collection, 62.1, University of Delaware Library.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Victorian Women Wood Engravers: The Case of Clemence Housman.” PDF. Forthcoming in Women, Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1830s-1900s: The Victorian Period, edited by Alexis Easley, Clare Gill, and Beth Rodgers, Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Oakley, Elizabeth. Inseparable Siblings: A Portrait of Clemence & Laurence Housman. Brewing Books, 2009.

Purdue, Melissa. "Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf: A Cautionary Tale for the Progressive New Woman." Revenant, no. 2, 2016, pp. 42-55. http://www.revenantjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Article-3.pdf