Christian Soteriology in Fin-de-Siècle Literature and Culture

Like Laurence Housman, who was both a lifelong advocate for sexual liberation and a convert to Quakerism, Clemence Housman’s principles ranged from conservative to radical for the fin-de-siècle setting in which she lived and worked (Lovell 172). Cast by historians in the shadow of her more famous brothers, Laurence and A.E. Housman, Clemence’s body of work demonstrates the writer/engraver’s values where information surrounding her life fails us. The Were-Wolf (1890), The Unknown Sea (1898), and The Life of Sir Aglovale de Galis (1905) vary in setting and character, but are similar in their use of Christian allegory and symbolism. In The Were-Wolf, Christian’s sacrifice for his brother, Sweyn, which is analogous to Christ’s sacrifice for the world, is complemented by Laurence Housman’s illustrations, most of which communicate Christian symbolism, ranging from latent to overt. The verbal and visual clues Clemence and Laurence grant their readership are particularly focused on Christian soteriology, a branch of theology dealing with salvation. This is in accord with the turn-of-the-century culture in which Clemence wrote; eschatological anxieties surrounding atonement, redemption and salvation abounded at a time when new branches of religion were forming and doctrines were changing. This essay contextualizes these anxieties within Clemence’s first novel, The Were-Wolf, with some reference to her later works, to provide the reader with a brief look at the fin-de-siècle “crisis of faith” that seeped into the decade’s literature.

Born on the feast day of St. Clement, Clemence’s name was given to her by her mother Sarah Jane Housman, who practiced High Anglicanism, and consequently observed Saints’ Days (Oakley 2). Her father, Edward, was the son of Reverend Thomas Housman of Christ Church of Catshill, where the family attended weekly services and is buried (2). Edward’s second marriage to his cousin Lucy Housman influenced the family’s migration from High Anglicanism to Evangelical, or Low Church Anglicanism. While the family eventually stopped their observance of Saints’ Days, Elizabeth Oakley suggests that Clemence retained a veneration for sainthood that is expressed in her novels, if not her life, long after her birth mother died (2, 17).

The Housmans weren’t the only ones experiencing a transition in their faith. The turn-of-the-century “crisis in faith” was due in part to the Oxford Movement (1833-1841), also called Tractarianism, which was an effort to renew Catholic or High Church ideals in the Church of England (Guy 202). Naturally, the “crisis” was also an offshoot of the defining trait of the fin-de-siècle, decadence. The Decadent movement posed challenges to “Victorian moral conventions,” particularly those concerning identity (Murray i). Housman’s works are an embodiment of the opposition between critics of decadence and those fin-de-siècle writers who embraced it. Fittingly, Housman writes The Were-Wolf as a novel that counters Christian’s piety with White Fell’s paganism, a spiritualism which decadents also revived (Murray 43). White Fell’s character shares traits with the decadent-traditionalist contest; she is alluring and beautiful but needs to be approached with caution lest she prove dangerous; and in Rol, Trella, and Christian’s cases, deadly.

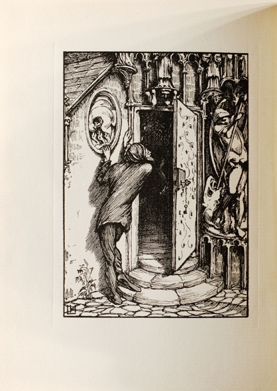

Figure 1. "Holy Water," frontispiece to The Were-Wolf (1896). Designed by Laurence Housman, Engraved by Clemence Housman

Figure 1. "Holy Water," frontispiece to The Were-Wolf (1896). Designed by Laurence Housman, Engraved by Clemence Housman

The protagonist in all three of Clemence Housman’s novels is tasked with salvation: of their loved ones, of those in need of saving, or of themselves. In The Were-Wolf in particular, as Shari Hodges notes, Housman presents “a religious parable, symbolizing the biblical tale of Christ's atonement for man's sin” (57). Christian dies trying to save his brother Sweyn from being killed by White Fell, but we can also think of his death as a Christ-like sacrifice for Rol and Trella, who die, not recognizing Satan in the form of White Fell until it is too late. The Were-Wolf’s frontispiece, entitled “Holy Water,” is one of the novel’s first indications of Christian as an archetype for Christian sacrifice. The image is meant to coincide with the scene in which Christian goes to a church to fetch holy water, which he believes will kill White Fell (Housman 54). In an alcove to the left of the church’s door is a pelican, which legend claims pierces its own breast to feed its offspring with its blood. In Christian art, the pelican is symbolic of Christ’s sacrifice for humanity (Ferguson 23). Laurence’s illustration foreshadows Christian’s self-sacrifice for his brother, Sweyn.

Figure 2. Photo by Mike Young at St Mark's Church, Gillingham, Kent. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. Photo by Mike Young at St Mark's Church, Gillingham, Kent. Wikimedia Commons.

It is important to note that holy water is a significant motif in Anglican theology. Believers are baptized with it to renounce original sin and accept the Holy Spirit (Avis 39). Baptism is one of the two sacraments recognized in the Anglican church, the other being the Eucharist. While both are necessary for salvation, the Eucharist is the sacrament that memorializes and actualizes Christ’s own salvation, his sacrifice for humanity. When Christian dies at the hands of White Fell’s axe, his spilled blood completes the sacraments necessary for salvation in the context of Anglican belief. Just as Christ dies on the cross so that humankind might live, Christian’s death grants Sweyn life and the salvation of Rol and Trella’s souls (106). Moments before he dies, Christian realizes “… that no holy water could be more holy, more potent to destroy an evil thing than the blood of a pure heart poured out for another in free willing devotion” (106). When Sweyn comes across his brother’s body, he clings to it because his soul is in “piteous need for grace from the soul that had passed away” (116). The narrator’s finishing statement, “And he knew surely that to him Christian had been as Christ, and had suffered and died to save him from his sins” is an explicit confirmation of Christian as a likeness of Christ (123).

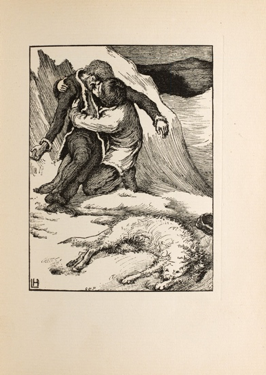

Figure 3. "Sweyn's Finding." Illustration by Laurence Housman, wood engraved by Clemence Housman, for The Were-Wolf (1896)

Figure 3. "Sweyn's Finding." Illustration by Laurence Housman, wood engraved by Clemence Housman, for The Were-Wolf (1896)

Clemence’s skills in subtlety raise the question of why the writer plainly ends her novel this way, especially when considered in tandem with The Unknown Sea’s epilogue, where the monstrous Diadoymeme and the hero Christian also lie dead as “God […] wipe[s] away all tears from their eyes” (314). Clemence’s transparency at the end of her works suggests a response to the crisis of faith. This staunch display of spirituality is in direct contradiction to what Ellis Hanson terms the “decadence in English writers . . . the fin-de-siècle fascination with cultural degeneration, the […] myth that religion, sexuality, art, even language itself, had fallen at last into an inevitable decay” (Hanson 2). Lastly, Clemence’s work also offers insight into her character. The Times obituary for Laurence describes Clemence's brother as “a born radical in a conservative’s skin” (Holton 232) but also adds, in brackets, “(a family inheritance)” (232). Clemence Housman, like her antagonist in The Were-Wolf, eclipsed binaries, sexually, spiritually, and politically, and her novels lie as testament to her dissidence.

Emily Proulx, Ryerson University, 2018

Citation: Proulx, Emily. "Christian Soteriology in Fin-de-Siècle Literature and Culture." Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Emily Proulx, et al, COVE Editions, 2018, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/were-wolf/christian-soteriology-fin-de-si%C3%A8cle-literature-and-culture.

Works Cited

Avis, Paul D. L. The Anglican Understanding of the Church: An Introduction. SPCK, 2013.

“Christ Church Catshill.” Housman and Christ Church, www.christchurchcatshill.org.uk/aboutus.html.

Ferguson, George. Signs & Symbols in Christian Art. Oxford UP, 1959.

Guy, Josephine M. The Victorian Age: An Anthology of Sources and Documents. Routledge, 2005.

Hanson, Ellis. Decadence and Catholicism. Harvard UP, 1997.

Hodges, Shari. “The Motif of the Double in Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf.” Housman Society Journal, vol. 17, 1991, pp. 57-66.

Holton, Stanley. Suffrage Days: Stories from the Women's Suffrage Movement. Routledge, 2002.

Housman, Clemence. The Life of Sir Aglovale De Galis. Internet Archive, 7 Jan. 2010, archive.org/details/Aglovale.

Housman, Clemence. The Unknown Sea. Duckworth, 1898.

Housman, Clemence. The Were-Wolf. Illustrated by Laurence Housman. John Lane at The Bodley Head, 1896.

Knight, Frances. Victorian Christianity at the Fin De Siècle: The Culture of English. Religion in a Decadent Age. I.B. Tauris, 2015.

Lovell, Percy. Quaker Inheritance, 1871-1961; A Portrait of Roger Clark of Street. Based On His Own Writings and Correspondence. Bannisdale Press, 1970.

Maltby, Edward. The Anglican Baptismal Service Considered: In a Letter to the Lord. Bishop of Durham, &c., &c. John Johnstone, 1843.

Murray, Alex. Landscapes of Decadence: Literature and Place at the Fin-De-Siècle. Cambridge UP, 2017.

Oakley, Elizabeth. Inseparable Siblings: A Portrait of Clemence & Laurence Housman. Brewin Books, 2009.

Osborne, Kenan B. Sacramental Theology: A General Introduction. Paulist Press, 1988.

Spinks, Bryan D. Two Faces of Elizabethan Anglican Theology: Sacraments and. Salvation in the Thought of William Perkins and Richard Hooker. Scarecrow Press, 1999.