Figure 1. Detail from "The Race," by Laurence Housman; wood engraved by Clemence Housman, for The Were-Wolf (1896)

I teach at Ryerson University, an institution that prides itself on applied learning. Ryerson was the first Canadian university to support the initiatives of the Central Online Victorian Educator (COVE), of which I’m a founding member. Committed to empowering students to recognize and take responsibility for their role as producers—rather than simply consumers—of scholarly knowledge, I draw on digital humanities pedagogies in my classes. When the COVE toolset became available, I developed an experiential course in scholarly editing whose outcome would have real-world effect. In W2018, my graduate course in Digital Publishing transformed 13 master’s level students into a collaborative editorial team. Each 3-hour class was divided between discussions of theoretical readings on issues in the digital humanities and editorial activities, including collaborative decision-making, field trips, html workshops, and online experimentation. Students worked through a scaffolded series of assignments that enabled them to gain the skills and knowledge they needed to create a publishable scholarly edition governed by the MLA standards of accuracy, adequacy, appropriateness, explicitness, and consistency.

Learning such practical skills alongside the theory was an enriching experience. Too often in academia we learn about a skill, but very rarely do we get the opportunity to put it into practice and have something to show for it. This course was a testament to unifying forces: hands-on experience with “textbook” education, and how digital and print can be married together as opposed to a strict dichotomy. Danielle DiFruscia

The editorial workflow, itemizing collaborative tasks and individual assignments, looked like this:

| Week | Collaborative Editorial Tasks | Individual Assignments |

|

1 Jan 17 |

Selecting the Copy Text | In-class group work |

|

2 Jan 24 |

Preparing the Copy Text 1: Physical to Electronic format | Worksheet 1 on an online edition due on D2L |

|

3 Jan 31 |

Establishing Editorial Principles, Goals Preparing the Copy Text 2: Semantic Markup |

Worksheet 2: Document Analysis of assigned Were-Wolf pages due on D2L |

|

4 Feb 7 |

Establishing Editorial Team and Collaborative Methods, Work-flow for proofing | Semantic markup exchanged with partner; proofing feedback due Feb 10 |

|

5 Feb 14 |

Preparing the Copy Text 3: Editor approves final text for accuracy, makes it “annotatable” on COVE Finalizing the marked-up text and working with illustrations |

Revised, final markup of assigned pages due to Editor and Editorial Technician for final accuracy check and document completion |

|

6 Feb 28 |

Developing plan for Editorial Apparatus, Annotations, and filters, with rationale Assigning responsibilities for essays in Editorial Apparatus Establishing editorial style sheet |

|

|

7 Mar 7 |

Developing criteria and procedures for annotation of the text | Worksheet 3 on Editorial Annotations & Essay due on D2L |

|

8 Mar 14 |

Developing criteria and procedures for image annotation | Annotations of text exchanged for proofing (proofing feedback due Mar 17) |

|

9 Mar 21 |

Developing criteria and procedures for timeline; using the annotation tool and timeline tool | Image annotations exchanged for proofing (proofing feedback due Mar 24) |

|

10 Mar 28 |

Refining plans for Editorial Apparatus essays, cross-referencing, and hyperlinking

|

Finalized text and image annotations due in COVE & on D2L; timeline annotations exchanged for proofing (proofing feedback due Mar 31) |

|

11 Apr 4 |

Reviewing Annotations (image, text, timeline) against editorial goal and rationale; cross-referencing and hyperlinking. How to create essay as a document in COVE. | Timeline annotations due on COVE & D2L; Essays exchanged for proofing (proofing feedback due Apr 7) |

|

12 Apr 11 |

Preparing the COVE submission form

Editorial Team Self-Assessment |

Editorial Essays due on COVE and D2L by noon |

| April 18 | Editorial Self-Assessment Worksheet 4 due with time log in D2L | |

| April 30 | Were-Wolf edition submitted to COVE for peer review | Editor’s responsibility |

This course has challenges because of its number of assignments and amount of research that must be done within 12 weeks. However, the amount of work gives me the essence of working collaboratively and effectively. I was able to find most challenges in this course fathomable through working with my peers. Erni Suparti

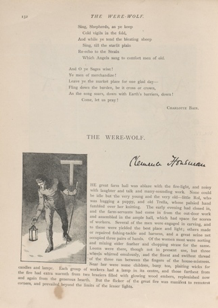

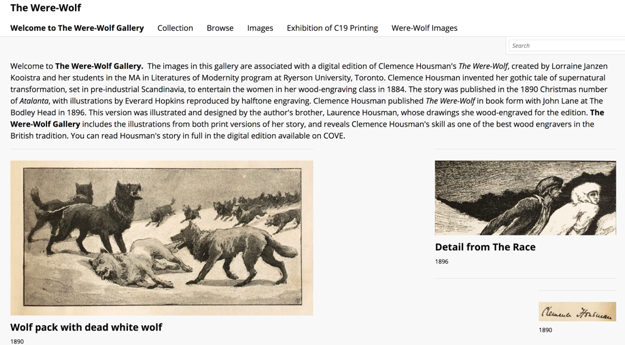

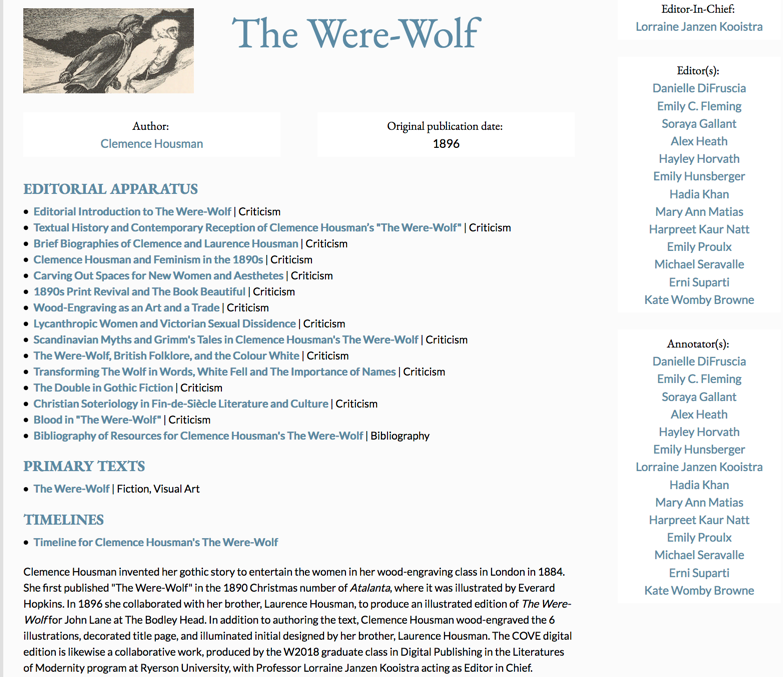

Both our methodology and our subject matter involved transformation and collaboration. Our text was The Were-Wolf, a fin-de-siècle gothic novella about an alien woman who transforms into a werewolf and preys upon a remote Scandinavian community. Clemence Housman (1860-1955) invented the story to entertain the women in her wood engraving class in 1884. She published the gripping tale twice in her lifetime. In 1890, it appeared as the Christmas number of Atalanta, a progressive magazine for women and girls, with illustrations by Everard Hopkins (1860-1928). In 1896, John Lane, the avant-garde publisher of beautiful books at The Bodley Head, brought out an edition with wood-engraved illustrations by Clemence after the pen-and-ink designs of her brother, Laurence Housman (1864-1959), with whom she lived and worked her entire life.

Figure 2. Everard Hopkins for Atalanta (1890); Figure 3. Laurence Housman for The Bodley Head edition (1896)

Just as the werewolf has long been a trope of transformation in the popular imagination, so too has mediation served as a mode of transformation in storytelling. In this class, we self-reflexively engaged the transformative powers of re-presentation and re-mediation to publish a late-Victorian illustrated book as an annotated scholarly edition for online users.

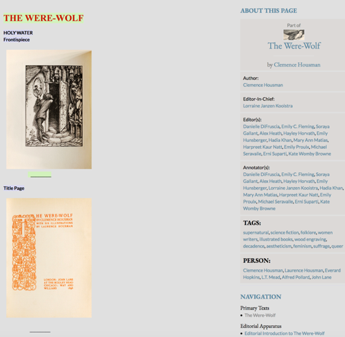

Figure 4. Screenshot of the Annotated Edition

This was an entirely alien and exciting experience because the process was not merely a transfer of The Were-Wolf into a new media format, but rather each week we were engaging with the theories and practices required for the production of a digital edition of scholarly merit. Thus, the transformative elements of this process emerged from not only a critical treatment of Housman's work as a text with its own historical and contextual significance through which we were able to elevate our own reading of the novella, but also the incorporation of elements such as interactivity that embedded that very research into the text itself. Mary Ann Matias

Figure 5. Decorated title page and cover for Bodley Head edition, designed by Laurence Housman; Cover and first page of "The Were-Wolf" in Atalanta, with initial letter by Everard Hopkins, and Clemence Housman’s reproduced signature

Our work began with the material. Ryerson University Library and Archives (RULA) acquired a good copy of the 1896 Bodley Head edition of The Were-Wolf and I contributed my own copy of the Atalanta volume (1890). The editorial team’s critical first task was to select a source text for our COVE Edition, and students were at first divided over the two publications, with vigorous defenders on each side. Eventually, we agreed on the Bodley Head edition, on the grounds that it represented the close collaboration of author/engraver and illustrator, while the magazine story represented more control by the editor, L.T. Meade, over layout and illustration.

I was sure that the “right” choice was to include the Atalanta illustrations as they were the first ever images that accompanied Housman’s The Were-Wolf in published form, however I believe more team members voted for the inclusion of the Bodley Head ones. This made sense in hindsight as I had not entirely realized that Housman’s own wood engravings were used for the illustrations in the Bodley Head publication, but when the opportunity to include both on COVE was presented, it became clear that this was the perfect solution. Although I was initially embarrassed that I had not voted for what the majority favoured, it was not a failure because in the end, both sets of illustrations were included as a result of careful collaboration, and now our readers have even more artifactual material to browse through, thus enriching their reading/learning experience. Alex Heath

We agreed to document substantive variants in the Atalanta version in our annotations, and to include Hopkins’s photomechanically reproduced wash drawings at the appropriate places in the text. Our physical copy in RULA had a Times Book Club sticker in it and the bookplate of E.K Muspratt. Editor Kate Womby Browne’s research enabled us to locate our source book in time and space, since the Times Book Club only operated between 1905 and 1907—when it generated a publishing “war” by its give-aways and low rates. This crisis in publishing history added unexpected drama to our physical copy. Another surprising discovery unearthed by Kate’s research was that its owner, Edmund Knowles Muspratt (1833-1923) was a prominent industrialist with a PhD in medicine who, in 1917, became a Bodley Head author by publishing his memoir, My Life and Work, with John Lane.

Figure 6. Times Book Club sticker and owner's label in RULA copy of The Were-Wolf (1896)

With regards to digital publication in particular, I was struck by the importance of access to resources. This applies in several ways. Obviously, having access to the primary text (and different variations of it!) made a huge difference in what we were able to do and how we approached the edition in terms of trying to convey the materiality of the text. Handling the physical books provided an emotional attachment to the text, author, artist, and publisher which made me feel responsible to them – I owed it to them to do my best work. Emily Fleming

Digitization took place at Ryerson’s Centre for Digital Humanities (CDH), which I co-direct. Students participated in a best-practices demonstration on how to digitize old and fragile books, but the actual work was done by library technician Olivia Wong and my COVE RA Iris Robin, with help from CDH Project Manager Reg Beatty. Once the scans were prepared, we divided them into sections in individual student folders within a common Google drive: each editor was responsible for marking up a specific page run. Ryerson COVE RAs Iris Robin and Alex Ross ran a workshop to introduce the team to the COVE tagset and to familiarize them with cleaning up dirty OCR and applying html markup using the Atom text editor.

The first initial surprise and challenge was learning about HTML and Atom because I had never imagined doing that in an English course of all places. Hadia Khan

To accommodate our need to represent the work as an illustrated text online, the COVE team created two new in-line CSS rules: <div class=<“codex”> to indicate the text is designed to mimic the print book, and <div class="codex_line”> to lineate semantically. This enabled us to reproduce the layout of the page and provide the page numbers necessary for classroom study and citation (see fig. 4). In order to embed the illustrations into the html, we created The Were-Wolf Gallery using OMEKA software as our image repository. To realize our understanding of the book as an expressive form resulting from a process of collaboration, we needed to represent the materiality of the work in a digital way that pushed both the editors and the COVE team to the limit.

Figure 7. Screenshot of The Were-Wolf Gallery (http://omeka-s.rula.info/s/werewolf/page/welcome)

Most students found the html markup particularly challenging. After their individual sections were complete and graded, I worked intensively with Reg at the CDH to ensure consistency throughout the entire document, and then with the COVE team to achieve an accurate and adequate edition. Once set to “annotatable” in COVE Studio, the source text cannot be altered in any way, so this was a critical stage in our editorial work. We reached it about halfway through the course.

As a computer-illiterate person, I consider the valuable takeaways to be the skills of HTML that I learned, and the interaction with COVE as a platform, both of which required troubleshooting and collaboration with my peers to navigate. Because we were learning these skills together, we had to rely on each other to find solutions to our problems, and to collectively gain practical digital literacy that we can apply in many different work experiences after graduation. Emily Hunsberger

Early on, the class took a field trip to a nineteenth-century print shop in Mackenzie House, just down the road from Ryerson University. Here we worked with moveable type, compositors' sticks, engraved woodblock images, and printing forms, in order to "reverse engineer" (Reg’s term) our digital edition by learning how the physical book would have been made in the Victorian period. This was a game-changer. Students found a lot of value in this opportunity to touch the past, and the hands-on experience gave them insight into historical print production and the labour involved in creating and printing wood-engraved illustrations. Each student set a line of type and selected an engraved woodblock to print with it, using a Victorian hand press. In a write-up for the departmental website, Editor Michael Seravalle—a part-time high school teacher who plans to use The Were-Wolf in his own teaching—observed that “the challenges of this historical printing method may not have modern day applications to our own processes, but our course’s focus on exploring and experiencing the modern day challenges of digital publishing can be mirrored in our struggles with using HTML, navigating the COVE interface, and, of course, publishing and editing our own edition.”

Figure 8. Students learn letterpress printing at Mackenzie House

Student editors were responsible for annotating the same page run they had marked up in html; the idea was that each would gain expertise on a specific section of the text, which they could contribute to our growing pool of shared knowledge. If that page run did not include a Housman illustration, I assigned a Hopkins image from Atalanta. In this way, each student had one image and roughly the same number of pages to annotate. Working in pairs, students peer-reviewed each other’s assignments at every stage along the way, so that all work published on COVE was edited and revised before I saw it in my dual role as course instructor and editor-in-chief. Overall, I found that students took the responsibility of meeting deadlines and standards very seriously and worked hard to give their peers constructive and helpful advice on both style and substance.

The unique and invaluable aspects of this class were the encouragement of trouble shooting, collaboration, and confidence in a new language and understanding the potential of a relatively new medium. Ownership and responsibility for peer-reviewed components of the text was a new feeling which drove me to be a more vigilant reader and self-editor. Hayley Horvath

The class had many discussions on how and what to annotate; I recorded and posted our editorial decisions each week to keep the team up to date. Ultimately, we decided to use the pre-set filters offered by the COVE annotation tool: textual, linguistic, historical, cultural, and interpretive. Defining what we meant by these tags took more editorial discussion and documentation. In the end, our decisions made sense. Textual annotations documented substantive variants in the Atalanta magazine version and accounted for gaps in the pagination of the Bodley Head source text created by the blank pages on either side of full-page illustrations. Linguistic filters glossed words not in common use as well as names whose etymologies seemed important to the narrative. Historical notes explicated details of the story’s setting in medieval Scandinavia. Cultural tags provided information relevant to the work’s fin-de-siècle publishing context and social conditions. Interpretive filters annotated intertextual allusions, generic conventions, and illustrations. We also tagged the latter with a customized “illustration” tag for users who might want to filter for images (the COVE annotation tool allows editors to create custom filters as needed).

Although every student was required to annotate one image, they were not mandated to complete a certain number of textual annotations. Rather, they needed to use their editorial judgement to research and write appropriate annotations for their section of the narrative under two categories. The first was linguistic and textual; the second was historical, cultural, and interpretive. I marked every course assignment according to the same rubric: accuracy, adequacy, appropriateness, explicitness, and consistency.

These considerations specifically represent the most valuable take-away as they forced me to approach publishing from the perspective of the editor and the reader and challenged how I think of my audience and what form my work takes when publishing. Michael Seravalle

Annotating the source text was a challenge for students, who needed to imagine their undergraduate selves as end-users, and constantly ask: what would readers of the online Were-Wolf need or want to know? How can I provide information that enables users to interpret the text, without interpreting it for them? What is the best style for online address? The kinds of research they needed to do also stretched their scholarly capacities. Students consulted encyclopedias of medieval Scandinavia, dictionaries of the Bible, werewolf folklore, sources on fin-de-siècle literature and culture, and much more. I put library resources on reserve and created a folder on Google drive with a few of my forthcoming essays and some relevant archival documents I’d collected over the course of my own research. I encouraged students to use this folder to share materials they discovered with others on the team. This kind of resource sharing is familiar to scholars working on common projects, but is less familiar to our graduate students, whose academic experience is often governed by competition rather than collaboration. In their self-assessments at the end of the term, a number of students flagged the collaborative methodology as a highlight of the course.

Having been supported, encouraged, and corrected by other students in the cohort, all of whom are working towards a single cooperative goal rather than in competition with each other, will remain the most valuable experience of my time in university. Soraya Gallant

The most valuable take-away in my experiential learning about scholarly digital publishing has definitely been how to be a part of an editorial team and a collaborative effort. Harpreet Kaur Natt

Figure 9. Screenshot of the COVE Edition Page for The Were-Wolf

As a team, we identified topics that we thought needed the longer and more interpretive genre of the editorial essay (as opposed to the briefer, informative space of textual annotation). After discussion, each student selected a topic of interest to them to research and develop for the Editorial Apparatus. This required negotiation, as we wanted to avoid overlapping subject matter. Our essays aimed to provide users with brief (circa 1000 words), focused, and accessible information on The Were-Wolf’s contexts—publishing history, wood engraving, feminist activism, the New Woman, and sexual dissidence—and its interpretive frameworks— religious references, colour symbolism, the importance of names and naming, the werewolf archetype, and gothic conventions. As Editor-in-Chief, I took responsibility for writing the Editorial Introduction and an essay on illustration, and I also created a common Bibliography of Sources.

The way we engaged with the text from so many different avenues, and in such depth, truly made it a unique and enjoyable experience. Using a relatively unknown text as our source made our individual contributions (our annotations and editorial essays) to the academic community, however small, feel much more large. Danielle DiFruscia

In addition to annotating their assigned image and pages, and writing an editorial essay, students were required to publish at least one annotation for the collaborative timeline we created using the COVE timeline tool. We decided that the chronology would chronicle events relevant to the life and work of The Were-Wolf’s producers, as well as to the development of the genre of werewolf fiction and film in the period. Most students researched and wrote timeline annotations related to their editorial essay. As I’ve written extensively on Clemence and Laurence Housman, I added notes specific to the siblings’ biographies and collaborations.

Figure 10. Screenshot of the Timeline for Clemence Housman's The Were-Wolf

The COVE timeline tool is user-friendly and students really enjoyed adding historical events and images to it—so much so, that many added more than the single annotation required. Stretching from 1839 to 1959, the timeline opens with the publication of an early Victorian werewolf story—Frederick Marryat’s The Phantom Ship—and ends with the death of Laurence Housman, self-described as “the last Victorian.” The chronology documents numerous biographical events in the lives of Clemence and Laurence Housman, with one reference to the publication, in the same year as The Were-Wolf, of A Shropshire Lad by their famous older brother, A.E. Housman (1859-1936). The students were keen to recuperate Clemence Housman’s life and career from under the shadows of her brothers. We documented her publications—a pamphlet on wood engraving as an occupation for women (1887) and two novels, The Unknown Sea (1898) and the Life of Sir Aglovale de Galis (1905)—and her political activism as a feminist and suffragist who made banners for the cause and was jailed for refusing to pay taxes until she had full citizenship and the right to vote.

While it shouldn’t shock me, what I found most surprising in learning about scholarly digital publishing was the lack of female representation, and the literal lack of the female author’s body of text in the digital sphere. It came as a surprise because being a millennial, I am accus-tomed to having access to information, but what I don’t always realize is that this obviously does not encompass all information. There are still those female authors, poets and writers whose work has never been given a body, and if I’ve learned anything, the embodiment of a text and how you make it available to your audience is crucial. Emily Proulx

The students uncovered a rich mine of werewolf material between 1839 and 1959 and exposed an explosion of lycanthropic literature in the 1890s, a decade known for its sexual dissidence, gender hybridities, and social transformations. The timeline documents werewolf fiction in England, Scotland, United States, and Canada. Editor Soraya Gallant, a French Canadian, was particularly excited to locate Québécois writer Honoré Beaugrand’s “The Werewolves,” first published in The Century in 1898, and later collected into La Chasse Galerie and Other Canadian Stories (1900), on the timeline. As Soraya notes: “Beaugrand wasn’t the only one that saw the potential of werewolves in the Canadian cold: Clemence Housman believed that a film version of her werewolf story could easily take place in either Scandinavia or Québec” (Housman “Script,” Bryn Mawr Special Collections”). In addition to providing a timeline notation on the silent movie script for The Were-Wolf that Laurence and Clemence Housman worked on in the 1920s, Soraya provided numerous entries documenting the development of the werewolf film.

I loved spending so much time and learning new things just as the rest of our team was discovering them. We weren’t dusting off piles of academic writing on it, rather we had the honour of formulating our own. The Were-Wolf’s unusual voice, subject matter, and painstaking illustrations all imbued it with meaning and new avenues of exploration. After all, Clemence spent so long refining/revisiting/transforming it that it stands to reason it would continue offering us new threads to trace. Hayley Horvath

Over the 12 weeks of the term, we followed an editorial workflow that began with selecting and preparing a copy text and ended with submitting an annotated edition of Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf to COVE for peer review. After receiving two positive reports from the anonymous reviewers, we made our revisions in July. Our goal was to create an open-access edition of this gothic novella that could be used in classrooms around the world. Captivated themselves by the illustrated narrative, the editorial team envisioned an eager audience in undergraduate courses in Victorian literature and culture, Gothic literature, decadence, women’s writing, trans and gender studies, illustration studies, and folklore studies. Because information on both the author, Clemence Housman, and her story, The Were-Wolf, is scant, we believed the annotated edition would also be of interest to Victorian scholars and the general public.

While there were many challenges in being the first graduate class to create a digital edition for peer-review and publication on COVE—in many ways, our editorial team were also beta testers of the COVE toolset and interface—there were also many rewards. The students learned scholarly digital editing by doing scholarly digital editing. They helped trouble-shoot the COVE toolset. And they recovered and made accessible a little-known Victorian text and its remarkable author, Clemence Housman.

The opportunity to apply our learnings through hands-on work in COVE made explicit some of the challenges we read about and discussed, such as the fact that technical limitations must be considered. Although there were some frustrating aspects of working in COVE…, I think the takeaway from that is that digital scholarly publishing is still in its early stages, and has many growing pains to work through as it develops. Kate Womby Browne

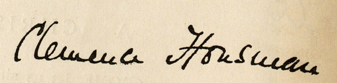

Figure 11. Clemence Housman's autograph signature, remediated via photomechanical reproduction for Atalanta (1890)