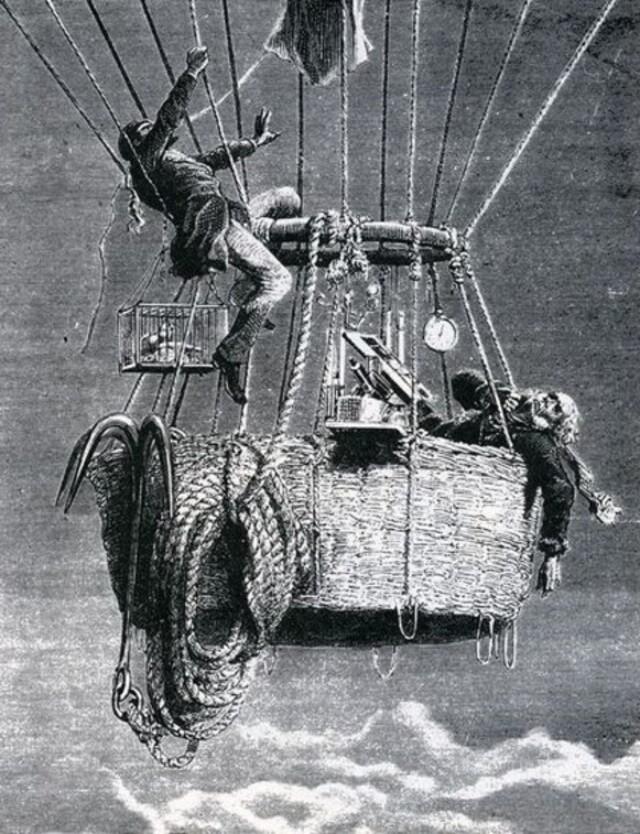

This illustration features meteorologist James Glaisher and balloonist Henry Tracey Coxwell ascending from Wolverhampton in their gas balloon in 1862. They rose an estimated 35,000 feet, by far the greatest height reached by a gas balloon at the time, and ultimately had to descend due to lack of oxygen. Glaisher and Coxwell’s flight was one of many during the Victorian era. In fact, Victorians became so obsessed with ballooning that historians referred to them as having caught “ballomania” (Wintz).

While ballooning had long been a form of aerial travel in Europe since 1783, representing “a utopian vision that promised a new social order and forecast man’s control over nature,” ballooning was mainly used for entertainment in Victorian England (Bossoh). As such, the scientific pursuit of ballooning was deemed unscientific, dangerous, and not worth pursuit for anything outside of entertainment (Bossoh). Following Glaisher and Coxwell’s 1864 flight, a mob ripped the balloon to shreds and set fire to Coxwell’s car (“Victorian Strangeness”).

Despite this, balloons for travel purposes started to grow in popularity, so much so that they made their way into literature, such as in Jules Verne’s 1863 novel Five Weeks in a Balloon. In this novel, Dr. Samuel Ferguson determines to traverse Africa from east to west entirely in a balloon (Verne). Later, in 1872, Verne published the better known novel Around the World in Eighty Days with a similar balloon adventure.

Balloons are also evident in The Little Lame Prince, although not overtly. In the Victorian era, balloons were mainly used for sight-seeing, whether that be for entertainment or for war reconnaissance (Bossoh). Dolor notably mentions floating, rather than flying, when he is looking at the sights around him or below him. For example, Dolor is “floating in the air on his magic cloak” when he sees “all sorts of wonderful things, ” (COVE, Chapter V), and he “floats” over the forest as he notices the “trunk, branches, and leaves” (COVE, Chapter VI). At the end of the story, the narrator states that Dolor’s flying is “less for his own pleasure and amusement than to see something or investigate something for the good of the country” (COVE, Chapter X) which also reflects the movement of balloons from entertainment to reconnaissance in war, scientific exploration, and communication between distant geographical points (Bossoh). Craik’s description of flying thus clearly incorporates the function and aesthetic of balloons in the Victorian era. Relating to disability in The Little Lame Prince, Dolor’s balloon-like floating allows him to become curious about the things he sees, such as the forest, and explore his surroundings. Dolor’s observational and curious travel on his cloak mirrors the kind of limited aerial exploration and overall passive entertainment balloons provided in the Victorian era. This also aligns with how Victorian scientists like Glaisher and Coxwell viewed balloons as tools to expand their scientific observation and curiosity, a curiosity much like Dolor’s. By portraying Dolor’s floating or flying like a balloon as a means for him to explore his environment and escape the confines of his tower, Craik thus reframes Victorian ideals of ability; she shows that new knowledge and experiences can come from alterative, even passive forms of movement rather than conventional, popular forms of movement or flying. Therefore, the images of Dolor floating above the world do not only embody the Victorian balloon craze, but also portray a reimagining of freedom, curiosity, and ability in non normative bodies.

Image citation: Laplante, Charles. “Glaisher and Coxwell.” The British Balloon Museum & Library, 1862, www.bbml.org.uk/timeline.