XLI

For “Is” and “Is-Not” though with Rule and Line,

And “Up-and-Down” without, I could define,

I yet in all I cared only to know,

Was never deep in anything but–Wine.

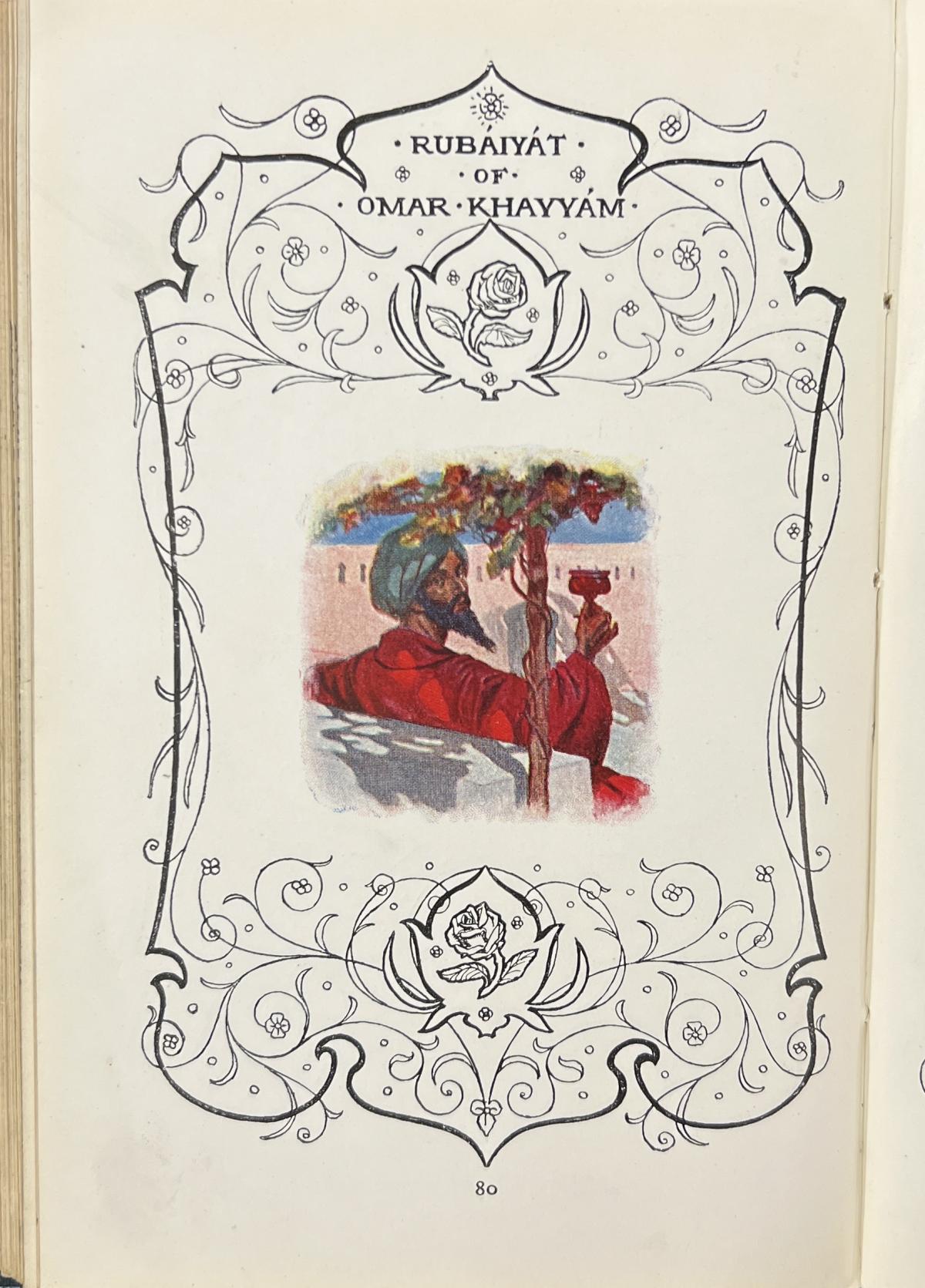

In Edward FitzGerald’s translation of Omar Khayyám’s Rubáiyát, the image of wine is used very frequently to represent a “carpe diem” philosophy. Many of the verses discuss wine as a simple pleasure of the human experience, a symbol for life’s fleeting nature and a reminder to take advantage of the joys available to us. The stanza above (XLI) is a fitting example of this theme, and paired with the image it faces in the “Heath Robinson” edition of 1907 (fig. 1), this passage may reveal more about the nature of FitzGerald’s translation than about the verses themselves. In the first two lines, the speaker — originally Khayyám, though the voice feels more detached and abstract in translation — meditates on the difference between “‘Is’ and ‘Is-Not’” and “‘Up-and-Down,’” crediting the distinction to the presence of “Rule and Line.” These lines, though somewhat difficult to decipher from a modern linguistic understanding, are essentially contemplating the objective nature of what is and what is not in contrast to the relativity of concepts like up and down. Through the scope of “Rule and Line,” the literal existence of a thing is unquestionable, whereas concepts such as up and down are entirely relative to one’s position, and therefore can not be determined through such prescriptive standards. The turn of this stanza takes place in the third line, wherein the speaker dismisses this philosophical conversation in favor of “...all I cared only to know,” which is wine. To compliment this message, this stanza faces an image of a stereotypical-looking Middle Eastern man — wearing a robe and turban, his long beard styled to a point — sipping a glass of wine under the shade of a tree, looking back over his shoulder to appear unposed and nonchalant.

In a discussion of how Orientalism affected the gift book industry — and Khayyám’s Rubáiyát, specifically — special attention must be placed on how FitzGerald’s translation encouraged the West’s appropriation of Persian culture. In the act of translating a poem written in a language he did not speak, FitzGerald had the power to reframe the verses, and he did so with the noted intention of making the themes and allusions within the verses feel more familiar to his anglophone audience. In her book On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, author Barbara J. Black describes FitzGerald’s translation technique as “[prettifying] the lines,” and asserts that “…the poem commands to be taken along on picnics and read under boughs […] The poem overly endorses ‘infinite resignation’ yet covertly recommends taking the book, reading it in polite company, and surviving long enough to pass it on to others. In effect, the brevity of life jars with the longevity of the text: the poem’s nihilistic message clashes with its empowering use” (62, italics added). By portraying the subject of this image (fig. 1) as relaxed, unposed, and simply enjoying a glass of wine in the shade, Robinson’s illustration serves as a direct reflection of this misinterpretation of the poem. It’s unclear exactly how much FitzGerald altered the message of stanza XLI specifically, but it nonetheless serves as an example of how and why English audiences misinterpreted “the poem’s nihilistic message” and appropriated Khyyám’s verses to best fit within their limited perspective of the world.

Works Cited

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. University Press of Virginia, 2000

Khayyám, Omar. Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Astronomer-Poet of Persia. Translated by Edward FitzGerald, London: Ernest Nister ; New York: E.P. Dutton and Co., 1907.