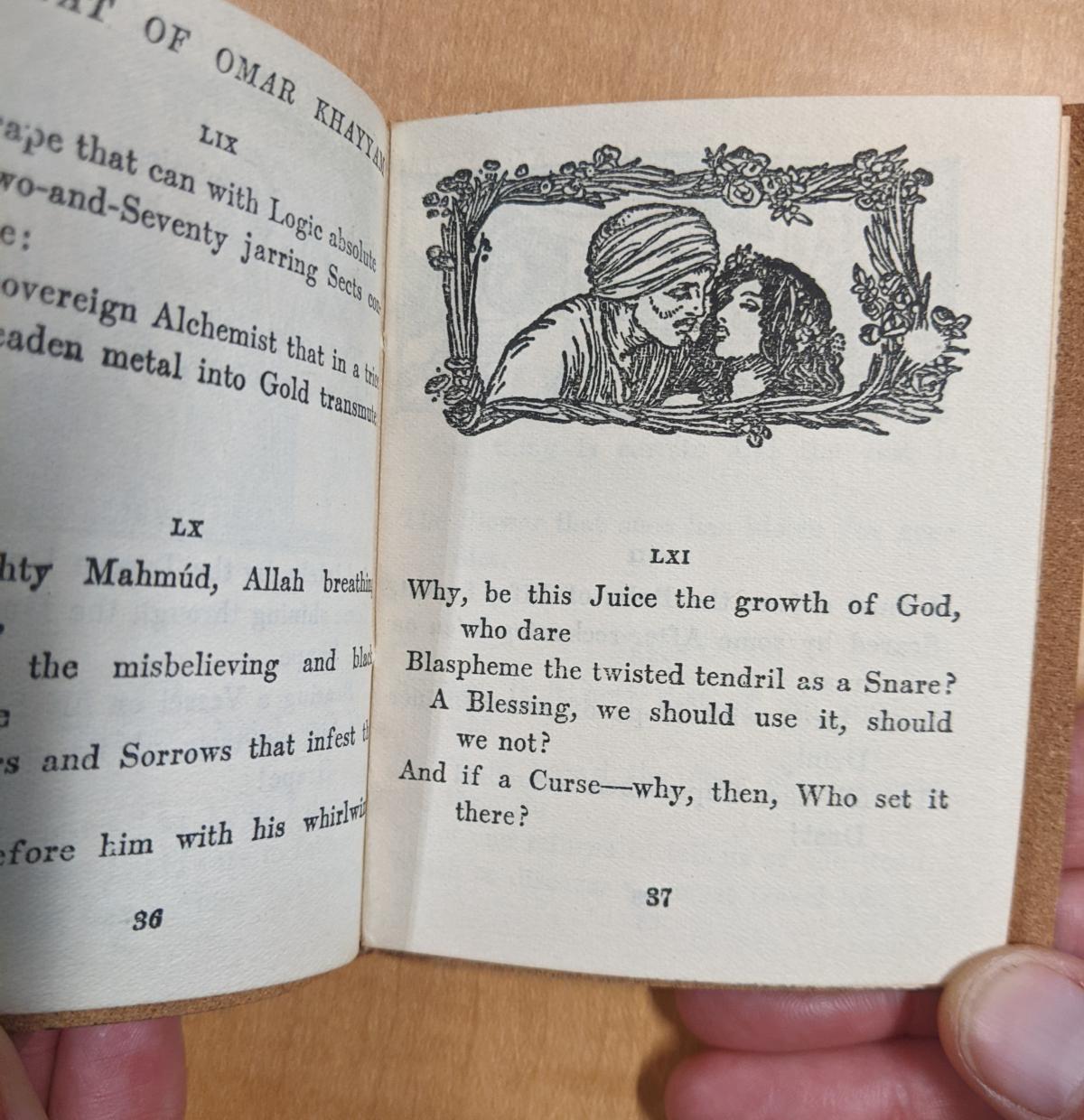

On page 37 of this book, we find one ruba'i and one illustration. Ruba'i LXI of this edition, reads as follows:

Why, be this Juice the growth of God, who dare

Blaspheme the twisted tendril as a Snare?

A Blessing, we should use it, should we not?

And if a Curse–why, then, Who set it there?

Breaking this ruba'i down, we can see it follows the standard AABA rhyme-scheme most of the Rubáiyát has. There are three questions here, with one line indented. This indentation serves to show us the narrator’s opinion on the subject, his main claim. He believes that wine is a blessing from God, or else why would it exist?

Going further, we can see that wine could be a metaphor for many things: the human experience, drunkenness, the human body, love, or sex. Sex and love are particularly plausible given the use of words like “juice, twisted tendril,” and “snare.” The later two words are metaphors of the male and female genitals.

This highly-sexual metaphor seems plausible given the illustration the publishers chose to accompany this ruba'i: a man in a turban leaning down over a woman with her hair down, they seem moments away from a kiss. The contrast is good, giving the image clear shapes despite the minimal details. The negative space and lack of background isolates the two: we see only them and they see only each other. The frame is botanical with blooms giving shape to the border, while also serving the purpose of preventing too sharp of a line; the flower in the woman’s hair is the same as those found encircling this romantic moment.

The two figures, despite the romantic setting, are portrayed in the stereotypical fashion of the Persian. To a Western/British audience, the turban and the suggestion of dark facial hair would signify his origins and ethnicity. Similarly, the way the woman is overtly sexualized (hair down, no obvious clothing, full lips) would identify her as Persian--as part of the Orient. Notably lacking from this illustration is any kind of cup, grape or “twisted tendril.” The image must be displaying the metaphorical interpretation of the ruba'i, then. This choice of illustration re-sexualizes, or at least overtly sexualizes FitzGerald’s translation. Thus, this ruba'i and this image serve as an example of how this edition of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is sexualized and feeds into the stereotyping of Western-Asain cultures and peoples.