This 1951 edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, published by Shakespeare House in New York, features Edward FitzGerald’s first-edition translation, originally published in 1859. A key identifying feature of this version is that it contains only 75 quatrains, making it easily distinguishable from FitzGerald’s later editions, which expanded the number to 101. This early translation is often noted for its poetic voice but very criticized for shaping the text into a reflection of Victorian sensibilities, while changing and overshadowing the philosophical and existential depth of the original Persian verse.

The edition presents a great example of mid-20th-century Western book design, subtly ornamental and built to last. The book is modestly sized with a distinctive two-tone combination: a buckram-style spine covered in a deep textured material mimicking leather, paired with rust-colored cloth boards. The latter is textured with a woven-like pattern that evokes traditional binding cloth. In the lower right corner, there is a gold-stamped medallion depicting Shakespeare (a nod to the publisher, Shakespeare House) set against a maroon-reddish background, which is surprisingly actual leather, and framed with tiny golden stars. The spine is bordered with a faint golden chevron strip separating the black faux-leather from the cover cloth, adding a tailored touch. The gold-stamped star motifs are also present on the spine, which, though restrained, is a poetic nod to the philosophical and celestial themes.

Its rectangular format and left-to-right layout mark it clearly as a Western production, designed to sit on a shelf with its spine art displayed outward. The typography inside follows suit too: roman numerals for each quatrain, ample spacing, and a clean, formal layout that gives more presence to the text. Or it could be argued that the simplicity of the pages is not to highlight the text but to bring attention to the illustrations. The pages themselves are a creamy ivory, somewhat thick and lightly textured, now slightly yellowed with age. They also carry a gentle aroma of old paper, unmistakably archival (in my opinion). There is also a “cozy library” aesthetic to this edition. It lacks the extravagant ornamentation seen in other versions of the text: no gilded borders except for the top, no lush floral arabesques, no vibrant colors. This makes it less of a "gift book" meant to dazzle at first sight and more of a collector’s object, a volume intended to be revisited quietly and thoughtfully over time, or to look good in between other books with a similar spine.

Besides the physical appearance, the illustrations are the most interesting aspects of this version of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Edmund J. Sullivan’s black-and-white pen-and-ink drawings transform Edward FitzGerald’s translation into a fully immersive experience. Sullivan (1869–1933), a British artist known for his highly detailed work, blends late Victorian and British traditional illustration with Art Nouveau styles. His illustrations for the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám are elaborate and densely detailed, even resembling fine etchings or woodcuts. They are filled with allegorical figures, celestial imagery, and esoteric symbolism. They are also not merely decorative but interpretive, adding visual depth to the poetry’s philosophical themes.

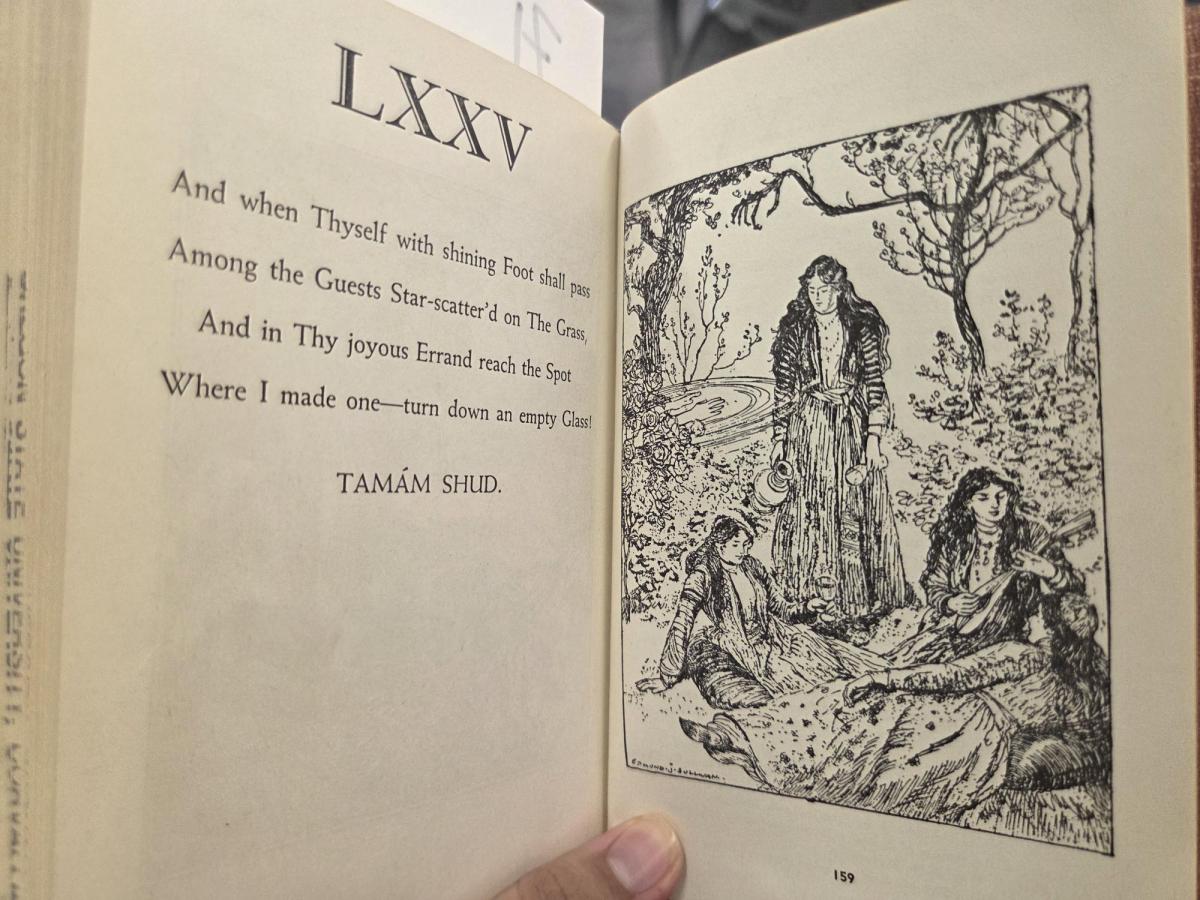

Here is one of my favorites (see figure 4) :

Edmund Sullivan closes the visual journey with an illustration featuring a scene that is tender, quiet, and very symbolic. At the center of the composition, there is a group of young women gathered in a peaceful, outdoor setting (likely a garden). One woman enjoys wine from her goblet as she listens to the music another is playing with their lute. A third reclines on the grass in a posture of relaxed thoughtfulness, also listening. The women are also arranged in a gentle arc, a crescent moon, which conveys new beginnings. But at the edge of the group stands a single woman, upright and somewhat defeated. She refrains from joining the others in drinking and music; instead, she holds a goblet upside down, an unmistakable representation of the final line of the quatrain: “Turn down an empty Glass!” Her gaze is directed almost outward, possibly toward the viewer, giving a subtle sense of awareness, like a knowing nod to those who remain behind. The overall atmosphere is gentle and dreamlike, almost pastoral, all while death looms in the background (one of the trees has a skeletal appearance, hovering over the woman standing).