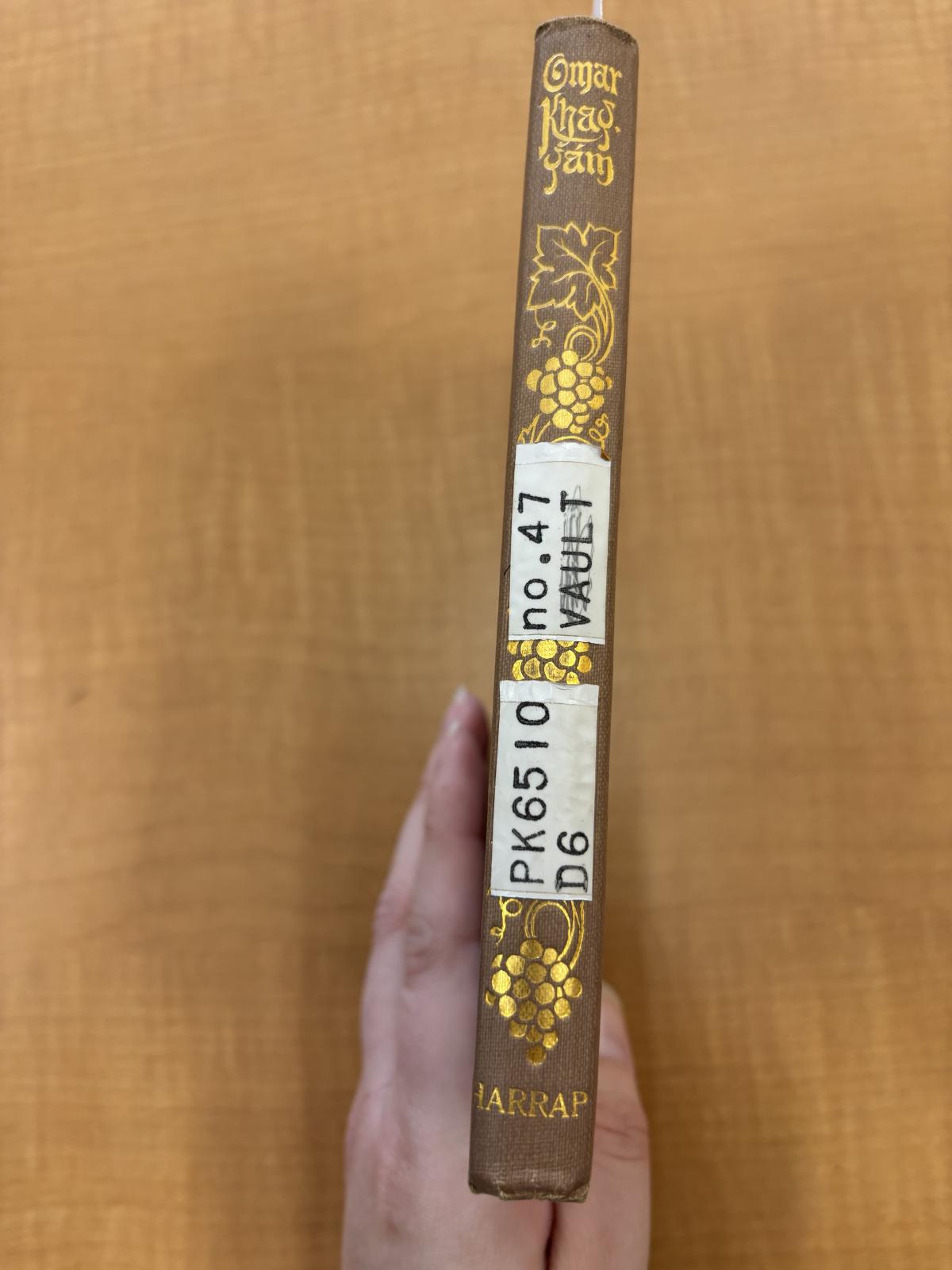

My edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám uses FitzGerald’s first edition text. It is considered a miniature book as it is 18cm (7.08in) in length; it is brown with gold colored letters on the title in a Persian design, and it has beveled edges. This edition has very little identifying information printed onto it. There is no author, translator, or publication date listed–although the OSU Library suspects this edition was likely published in 1917. There are no fewer than three publishers printed onto different pages of the book: on the spine is Harrap; on the back cover page: Printed by: Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Co. Ltd. London, Colchester and Eton England; and on the opening page: New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co.

There is also a name –Jamám Bud– which I originally suspected to be the illustrator of the images inside the book. The reason I suspected this name to be that of the illustrator is because the name is printed inside an end-chapter illustration on the page of the book as seen in image 1. The way the name seems to act as part of the illustration is why I surmised that this is the illustrator. However, according to the OSU Library’s database the images in this text are actually the work of Willy Pogany. I have found no information whatsoever related to the name Jamám Bud, however Willy Pogany was apparently a well known Hungarian artist who lived from 1882-1955. Willy immigrated to New York and worked as an illustrator and art director for various projects over the years. The images used in my edition do look like the style of paintings Willy created.

There are 92 pages in this book with 12 accompanying illustrations. The illustrations seem to be miniature paintings printed in black and white and mounted onto the page. Curiously the illustrations are not found at regular intervals throughout the book, (as in they don’t all occur once every ~7 pages). Rather the illustrator/publishers seemed to pick and choose which stanzas of the Rubáiyát to create images for. There is even a fifteen page gap in which no accompanying illustrations are used.

Another curious fact is that one illustration is not used with an accompaniment of the Rubáiyát’s prose. This image is pasted beside the title page of the book, and it depicts a lion in what appears to be a ruined Persian palace in the snow. I find this to be an odd choice as the illustrator used so few illustrations compared to the amount of stanzas available, why would he choose to paste an image at the front of the book? This can be seen in image 2.

On every page with stanzas of the poem (which are formatted in quatrains) there are ornaments and vignettes illustrated in a color that may once have been gold. The ornaments form somewhat Perisian shaped pots and jugs at both the bottom and the top of the page. There is also a flowerlike detail at the top of the page. The first letter on every page is enlarged to become as tall as nearly every line in the stanza. This first letter is also stylized in an “oriental” way. These details can be seen in images 1 and 4.

One other interesting thing about this edition is an introduction written ahead of the actual text of the Rubáiyát. This introduction seems to create a story that may or may not be true about Omar Khayyám and how the Rubáiyát eventually passed into the hands of FitzGerald. Some of this story does appear to be true as we know some of FitzGerald’s history, though the details about Khayyám are yet unclear to me. As we’ve discussed in class Khayyám may not even be the true author of the Rubáiyát, and yet this introduction writes as if this story is a well known fact. This introduction is shown in images 3 and 4.

I’ve also included pictures of the front cover of the book and its spine in images 5 and 6.