Black argues that the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is diminutive of Persian culture and Orientalist in nature because of FitzGerald's translation and the Gift Book Culture's appropriation of what Victorians’ defined as “exotic” elements of “the East.” Many editions of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám were bejeweled and adorned with locks to attain a “status” of “treasure book.” (Black 60) This aspect of the poem becoming more of a collectible for English and American fanatics alike devalues the poem’s cultural significance in Persia and the language contained within. Black also argues that because FitzGerald translated the poem and changed the meanings of various ruba’i throughout to add this exotic flare using words like “sultan” in place of phrases or words that have nothing to do with sultans. Illustrations that represent this “Persian exoticism” would fall under that framing as well. The overall argument is that the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám and its popularity as a gift book in European and American society makes it impossible to separate it from the Orientalist framework created in the 19th and 20th centuries.

My edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is not bejeweled or bedazzled in any way, unlike editions of the past. In fact, it is extremely plain, and would look just like any other hardcover book on a shelf in a bookstore or home back in the Victorian era. This edition would be less desirable for upper-class European or American collectors because of its plainness and so this version of the book would be a more economical choice for the middle and lower-middle classes. While that in and of itself is a break away from Black’s argument, these more common looking books would have still been bought with the intention of gifting to someone, in most cases. Does this make it less Orientalist? I would argue that it lessens the amount of “Persian exoticism” that Black says is inescapable for any edition of these gift books. The culture of buying the book purely as a collectible to give to someone is still apparent, even without the jewels, so it is hard to say this book is removed completely from Black’s argument. The more problematic issues with this edition lie within its pages.

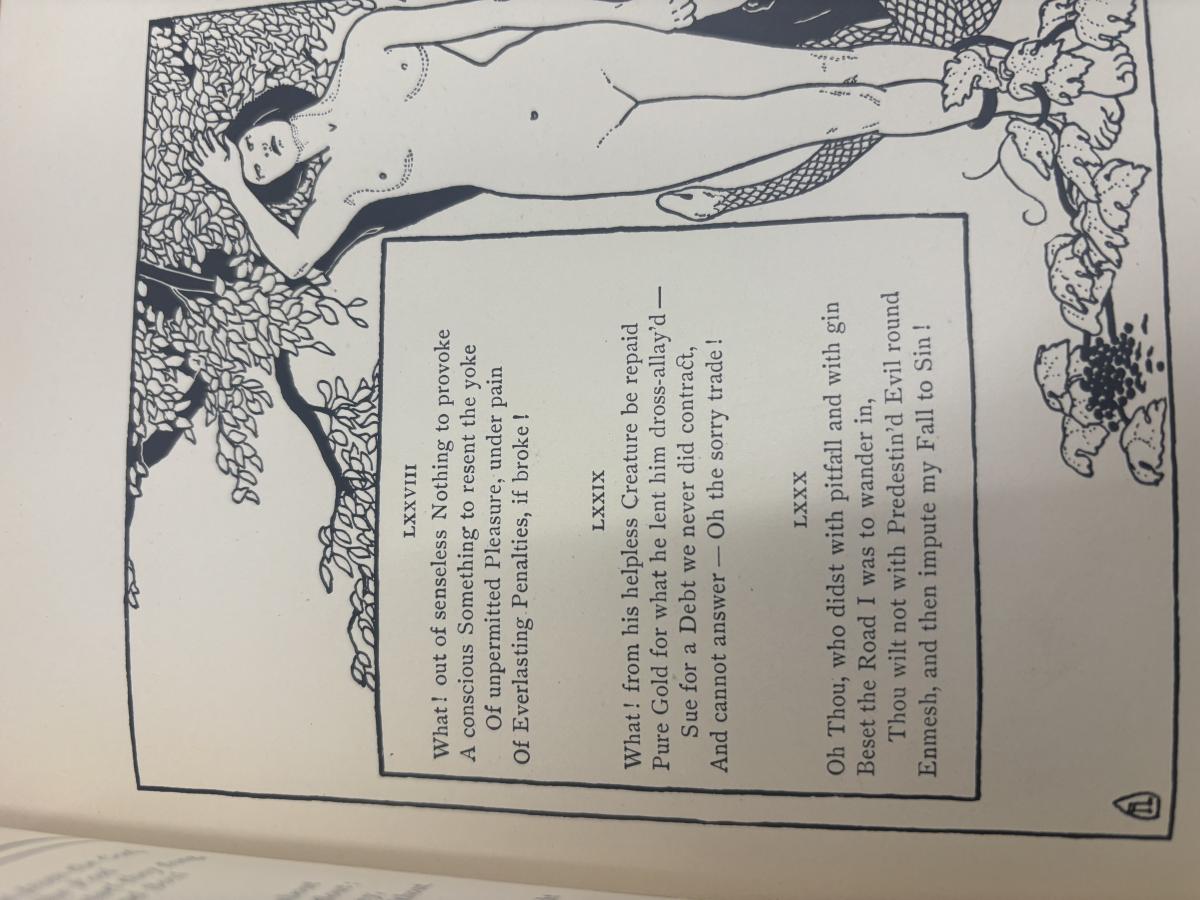

Each page within this edition is coupled with both the verse and black and white illustrations that depict people, landscapes, animals, vegetation, etc. While an illustration does not immediately indicate this text is Orientalist in nature, I think the issue with these ones specifically is their lack of attachment to the language of the poetry itself. For example, Figure A, the photo of a naked woman caught in a net, pleading to the heavens. One of the stanzas references Heaven, but the rest of them are about finding oneself within and enjoying your life on Earth through drink before you die. Lundborg did not capture that feeling here in this illustration and instead added a nude woman (one of the several) in a scene that doesn’t call for her being trapped in a net and pleading for her life. Another is Figure B, Lundborg’s depiction of soldiers marching into battle amidst a pile of skulls and bones. Nothing within any of the stanzas on this page produce a feeling that there is a battle ensuing in the narrative of the poem. The only imagery that fits is the pile of bones and skulls as the poem is talking about death and how time moves forward after we’re gone. What these images do for this book is not an enhancement of the philosophical ponderings of Omar, but rather they sexualize, grandize, and paint the Persian culture in a barbarous way, as Black points out in a quote from John Hay, “Omar sang to a half barbarous province; FitzGerald to the world.” (61) These parts of this edition support Black’s claim that these gift books are inherently Orientalist in nature because of the way the illustrations depict Persian culture as warmongering and erotic.

Within Figure C, the language of the poem with the woman against a tree and a snake wrapped around her legs, we see an interesting conversation between religious depiction and the meaning of the poem. This illustration is very obviously of Eve and the Garden of Eden scene from the bible. The language of the stanzas on this page are littered with religious dissent, attacking the idea that humans are born inately evil and sinful, and refuses to accept this ideology. Figure C is complicated because it includes another nude depiction of a woman, which I believe in this book feels eroticising of Persian women rather than adding to the narrative thoughtfully. But, the inclusion of Christian imagery into the poem's narrative, one which is critical of Islamic teachings in it's Persian text, gives it another layer of convolution. While this could be seen as a positive of the book as it is making connections between the narrative and philosophies, which is rare of this text, I don't think it can be framed that way 100%. "...dressing the Englishman in Persian costume or, in minstrel-show fashion, first dressing the Persian in English guise and then demanding a Persian 'impersonation.'" (63-64) I argue that this is what Figure C is doing here. The illustration is eroticising in nature because there is no logical reason within the text to be including nude images of people, let alone women. The inclusion of Christian imagery within an English translation of a Persian poem combined with that eroticism is doing as the quote above says. Figure C is an Englishman dressed in Persian costume, which "'Having left Persian poetry out, FitzGerald was putting English poetry in... he is exotic without being foreign.'" (64)

While this edition is not fancily bejeweled with rubies, emeralds, or any other precious gemstone, it is still connected to this history of Orientalism that Black argues is prevalent throughout the realm of gift books. While there may be an edition(s) out there that refutes Black’s claim, this edition does not.

Citations:

Black, Barbara J. “Fugitive Articulation.” On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 59–63.