In her book titled On Exhibit: Victorians and their Museums Barbara J. Black brings light to the acutely Victorian attraction of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám as the links with which the Persian book of poems is now forever chained to the Oriental. Although the book of poems was initially received as unpopular when FitzGerald published his translations, the Rubáiyát gained traction when the “Fitz-Omar craze” began somewhere around 1861 (Black, 59). By the turn of the century, the act of collecting and sharing luxurious and ornate copies of the Rubáiyát became more valuable than reading the text itself. Black argues that by wrapping up the Rubáiyát in gold leaf lettering and elaborate illustrations cemented the book of poems as a prominent instrument of English Orientalism.

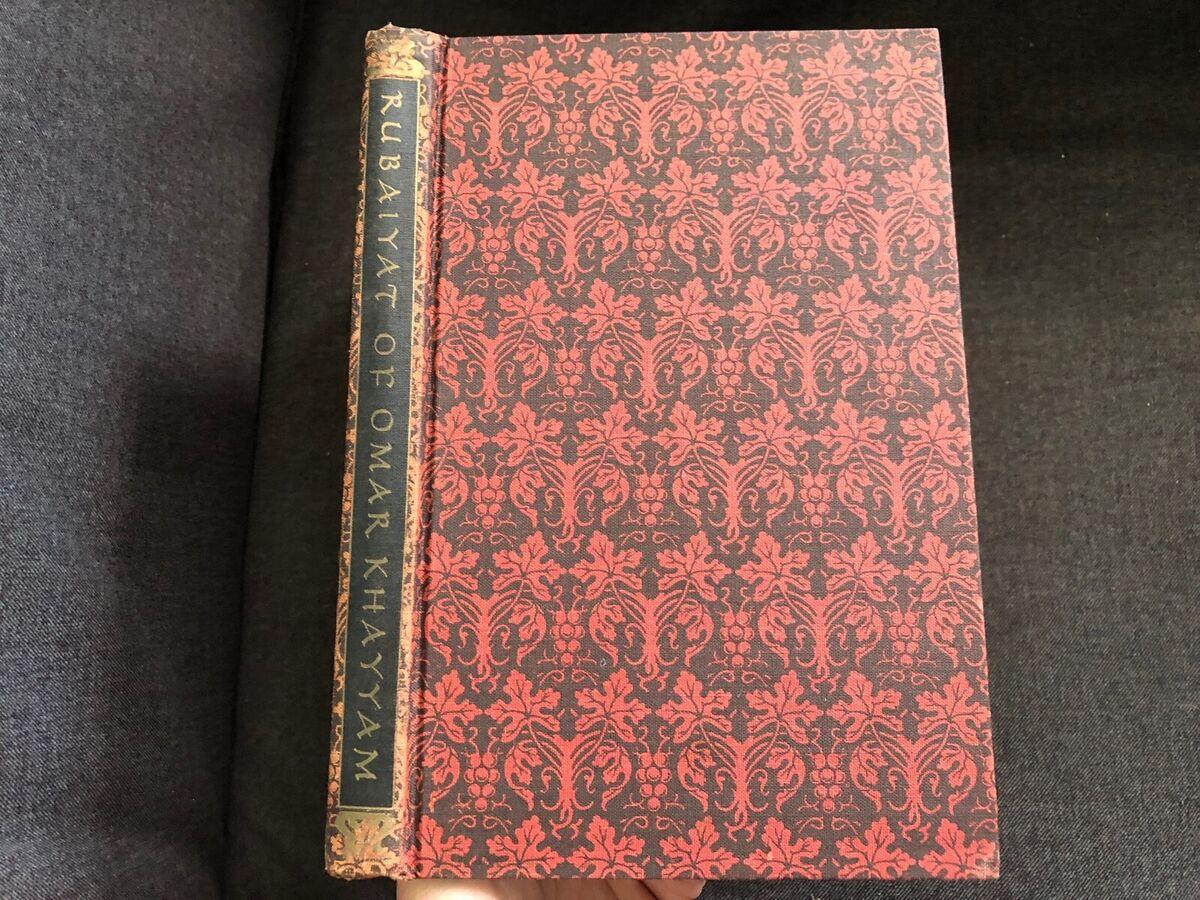

When considering the 1947 Random House publication of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám as inherently Orientalist, one must begin with the outside of the edition. Patterned with grape leaves, veins and fruit printed in red ink, the print lends itself to support Black’s argument, see figure 1. The Rubáiyát makes mention of wine numerous times and the feeling one can gain from letting go of seeking a god and submitting to the pleasures of life, whether that be wine or more wine. While the imaging of wine can easily be connected to the content of the poems, the pattern simultaneously boils down the deeper meaning of the poems into an excuse to drink. This forgoes why Khayyám invites the reader to consume in the first place. Yet, the color of the pattern is a reference to the deep red orange pigment specific to Persia and the natural stone native to the region used to create the red color. In addition, grape plants are native to the Persian landscape which then puts Black’s argument into question. If the materials used in the effort to make the book luxurious directly tie back to Persian plants and stones are they inherently Oriental? Orientalism, as Said puts it, is more or less a European dream of the Eastern world. Therefore, if exports of Persia were used, I would argue that the cover of this edition does not subscribe to Black’s argument as the materials used ground the reader in the Persia that actually existed, not an imagination of “exoticism”.

Random House’s 1947 edition contains traits specific to the Gift Book with the books vibrant and detailed illustrations that can be found on every third page. (in the first version), and every fourth page, (in the second and third versions included in the edition). These illustrations often contain men of financial means enjoying a sip of wine with one woman or many women, see figure 2 and 3. When observing these petite illustrations closely the intricacies of each figure’s garments, utensils and down to the beard hair on the men included in the illustrations. Upon first glance, the illustrations feel Oriental; they don’t necessarily depict anything uniquely Persian, (aside from their dress perhaps). Rather, they seem to elevate the rudimentary understanding of the poem mentioned in the previous paragraph by highlighting excess and grandeur that English audiences might think of when they imagine Khayyám’s home country. The edition includes a blurb on the last page crediting Mahmoud Sayah with the illustrations. The blurb details his Persian background and his inspiration for the illustrations. When completing the illustrations, Sayah followed the art style of Persian Miniatures that can be defined as miniature paintings found in literature that entail a layering of paint in order to achieve the brilliant color tone of the illustrations. Sayah being Persian himself, (although, the edition claims that he is Iranian and of the same country as Khayyám), and the distinctly Persian mechanism of painting refutes Black’s claims of this edition subscribing to the colonial Gift Book culture. These are not images shaped by the Westerner’s imagining of Persia, they are not shaped by Orientalism, they are shaped by Persian art and craftsmanship. The illustrations are rooted in Persian practices in addition to being crafted by a Persian person allowing for an admiring of Khayyám’s Persia as opposed to a festishization of Persia as an exotic “other” land.

This specific edition’s lush decorations bleed onto every page with interesting borders on every one of the book’s one hundred and fifty pages. The text of the book as well as the illustrations don’t take up the entire page but are centered on the page by a rotating background of prints. Each one of the four prints used for the bordering contain images of the exotic with peacocks printed on one and butterflies printed on the other. Both the peacock and the butterfly lend themselves to Said’s claim of the Orient as a European invention. The borders imagine a version of Persia colored with beautifully feathered birds and colorful butterflies perpetually flapping their wings as the Persians depicted in figures 2 and 3 drink wine. A Persia that is defined by the marking of the European imaginations. Yet, these prints that hypothetically perpetuate Orientalism, also work against Black’s argument. The animals and insects depicted in the border patterns are creatures native to the Persian environment as well as the peacock being a frequent visual tradition of Persia, (Berlin, High Museum of Art). The native ecology found within this edition coupled with the attention to important Persian symbols disputes Black’s claim. Similar to the illustrations in figures 2 and 3, the exuberant art and prints included can be traced back to Persia’s environment and artistic culture. Due to the very real ecological and cultural presence of the materials and illustrations present in this edition, I would argue that Random House’s 1947 edition does not subscribe to Colonial Gift Book culture. Instead, the edition actively refutes Black’s claim by entrenching all the trappings of the Gift Book in Persian tradition.