In her article On Exhibits: Victorians and their Museums, Barbara J. Black argues about the inherent devaluation of gift books, simply through their ability to achieve the status of gift book. She centers her text around the idea that the available number of editions grants the poem status of treasure, which robs the poetry of its intrinsic value. In other words, spreading the perception of the gift book as a “gem connotes the poem’s talismanic value,” as opposed to its value as a poem, and instead becomes just another thing that the West has appropriated for its own gain, becoming horribly objectified in the process (61). Black argues that FitzGerald’s refinement of the language was done with the intention of appealing to the Western view of the "Orient" as an idealized concept, and a more Western, Christian audience who would view the poem as a piece of "exotica." She further claims that FitzGerald succeeds in “dressing the Englishman in Persian costume or, in minstrel-show fashion, first dressing the Persian in English guise and then demanding a Persian ‘impersonation,’” and that the appeal of the poem lies in its intimacy, its idealization, and its indulgence (64).

My edition supports Black’s argument that Western ideals have a tendency to appropriate and incorrectly interpret—in a mocking manner, either intentionally or otherwise—aspects of other cultures as a form of oppression. The language of the edition itself, as addressed in Black’s writing, lends itself to perpetuating the idealized vision of the Orient that is present in certain lines and stanzas, such as the references to the Sultan and the Sultan’s turret, which are not accurate translations of the original poem, but rather Victorian ideals superimposed over a foreign text. The oppression of the cultural context within which the poem existed also becomes evident through the illustrative style. While this gift book does not display overtly appropriating images, the burial of Persian influence in favor of other “foreign” images, most of which draw inspiration from white Eastern cultures and Greco-Roman imagery (see image 1), presents an image of palatable foreign-ness that maintains an exotic look of otherness without blatantly sexualising Middle Eastern bodies, yet in doing so leeches the cultural significance and influence from the text.

Given that the illustration featured in this gift book draws heavily from Greco-Roman imagery and Western conceptions regarding the personification of Death, the images, interestingly, do not fully fit in with FitzGerald’s idealistic translation. The garb in which the figures are featured does not seem to match Persian clothing, and instead looks almost Russian (see image 2). This becomes its own form of oppression, as the illustrator sought inspiration from an entirely different culture, and created images that suited his tastes of ‘foreign enough’ to appeal to the audience, but "white enough" to remain palatable. In a sense, the illustrative style values the beauty of the imagery it presents, and even presents the nude form as indicative of beauty (see image 3), rather than a subject of inherent sexualisation, but the fact remains that these values feel misplaced in their whiteness. The Orientalist impulses that would have informed both the translation and illustration present a sort of catch-22: in drawing inspiration from cultures other that Persia, the illustrator buries the significance of the original culture to which the poem belonged, yet, as the translation itself suggests, idealizing the culture in the name of audience appeal is disrespectful in its inaccurate depictions of the culture to which the poem belongs.

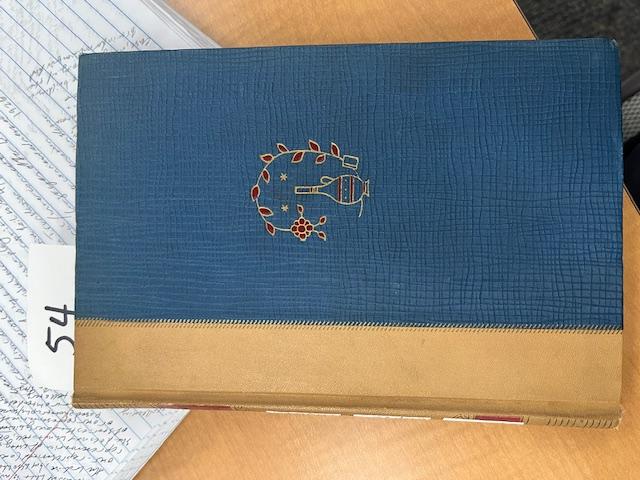

The cover lends itself to this critique for similar reasons. The plain blue cover holds a simple, small illustration at its center; a vessel sits beneath a flowering vine, pressed in gilt and minimally colored (see image 4). It does not boast mock script in the style of Middle Eastern writing systems that would draw undue attention to itself; within the pages, the font is rendered in a simple serif style. The smallness of both the cover and the image run parallel to Black’s argument that “its small dimensions delineate what Susan Stewart calls ‘collapsed significance’…the poem’s value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness” (61). The size of the cover is almost coy, begging to be opened, its minimalistic style inviting attention. And still it begs the question regarding the effect of effectively scrubbing the influence from all but the translation, creating a jumble of almost-cultures to which the poem could be ascribed, yet offering few definitive answers or delineations.

In considering Black’s argument, this edition upholds a tendency toward Orientalism, though in a much quieter way than she suggests. The cover is not flashy, nor is the appearance of the text; the illustration feels familiar in its simplicity and careful linework, the images keeping in line with the stanzas they interpret. Yet the fact remains that scrubbing the influence and cultural touchstone from a work denies it origin; it is appropriated for use by another culture, to be treasured and kept, but with all meaning and importance stripped from its lines. Mentions of a sultan offer a Persian pastiche, while Greco-Roman illustrations decentralize the work itself. While this edition does not lend itself to the flashy, brazen Orientalism that Black suggests, it nonetheless exemplifies the appropriating tendencies of Western culture and the ease with which it steals and reorients cultural artefacts for its own gain.