According to Britannica, cultural appropriation is when “members of a majority group adopt cultural elements of a minority group in an exploitative, disrespectful, or stereotypical way.” This definition is neat, simple, and generally meets modern-day examples of cultural appropriation. But this definition doesn’t fit very well for the gift books of Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam. This poem was translated from Persian to English but then dolled up with ornate Persian-inspired art, not intending to erase the Persian influence but to increase it. Every new copy of the Rubáiyát with gold inlay and colorful illustrations of caricatures of Persians makes the poem more ‘exotic’ and thus more desirable.

It’s this desire to make the Rubáiyát more exotic, more Persian, that Barbara Black argues is a special type of cultural appropriation because the decadent artwork that inherently ties the Rubáiyát to Persia is for no greater purpose than aesthetic. Black writes in On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums that “This poem’s value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness. Khayyám’s verse remains entrenched in the categorically Oriental, in the land of seers and Eastern serenity” (61). This results in the objectification of the Rubáiyát, which erases its cultural significance and meaning (61). By latching onto the aesthetic and presentation of the book, the humble message that Khayyam wrote is suffocated by jewels and embellishments.

However, the Rubáiyát of a Scotch Terrier seemingly strays from Black’s definition of cultural appropriation. The edition doesn’t have decorative drawings of caricatures of Persian people and fancy jeweled drawings. There isn’t any trace of Persia, which would theoretically absolve it from cultural appropriation. However, this isn’t the case. Sewell used a Persian poem as a foundation and made a parody of it, then erased its Persian roots and the humble message of the original poem, and thus committed cultural appropriation.

The drawings in Rubáiyát of a Scotch Terrier have no attachment to Persia, as the drawings of the Scottish terrier are somewhat realistic. Figure 1 shows an image of the Scottish terrier getting in trouble with the maid. The dog doesn’t have dramatized and stereotypical features like the Siamese cats did in Disney’s Lady and the Tramp. In addition, the drawings are black-and-white, not decadent and flashy. This edition of the Rubáiyát was clearly meant for children who are immune to bejeweled covers and beautiful illustrations when dogs are involved. This breaks the trend Black critiques because it doesn’t try to manually inject Persian culture for aesthetic purposes. This edition was written by an American dramatist and remains true to American and English Roaring Twenties culture. It could be argued that this edition isn’t cultural appropriation as no pictures depict Persians stereotypically. However, nothing connects this piece to Persian culture. Children who would have read this book wouldn’t have known the poem's origin. They would have believed that the Rubáiyát was a Western creation. Persia is erased, creating a unique case of cultural appropriation by cultural erasure.

Although the children reading the book might not have known the origins, the adults who would have bought the book would have. Therefore, Black’s argument can’t be entirely ignored because the cultural significance of the Rubáiyát is still being marketed. This is especially true when reading the poems. Figure 2 is a picture of one of the stanza III. It is very similar to FitzGerald's translation, especially towards the end. In FitzGerald’s addition, the last line reads “And, once departed, may return no more,” and in this edition it reads “And once that happens I can sleep no more.” The book may be meant for children, but parents are buying it. Any adult scanning this edition before buying would recognize the verse, its humor, and the culture it is capitalizing on. This edition is still using the Rubáiyát’s reputation, cultural weight, and glamor to profit off of which supports Black’s argument of cultural appropriation.

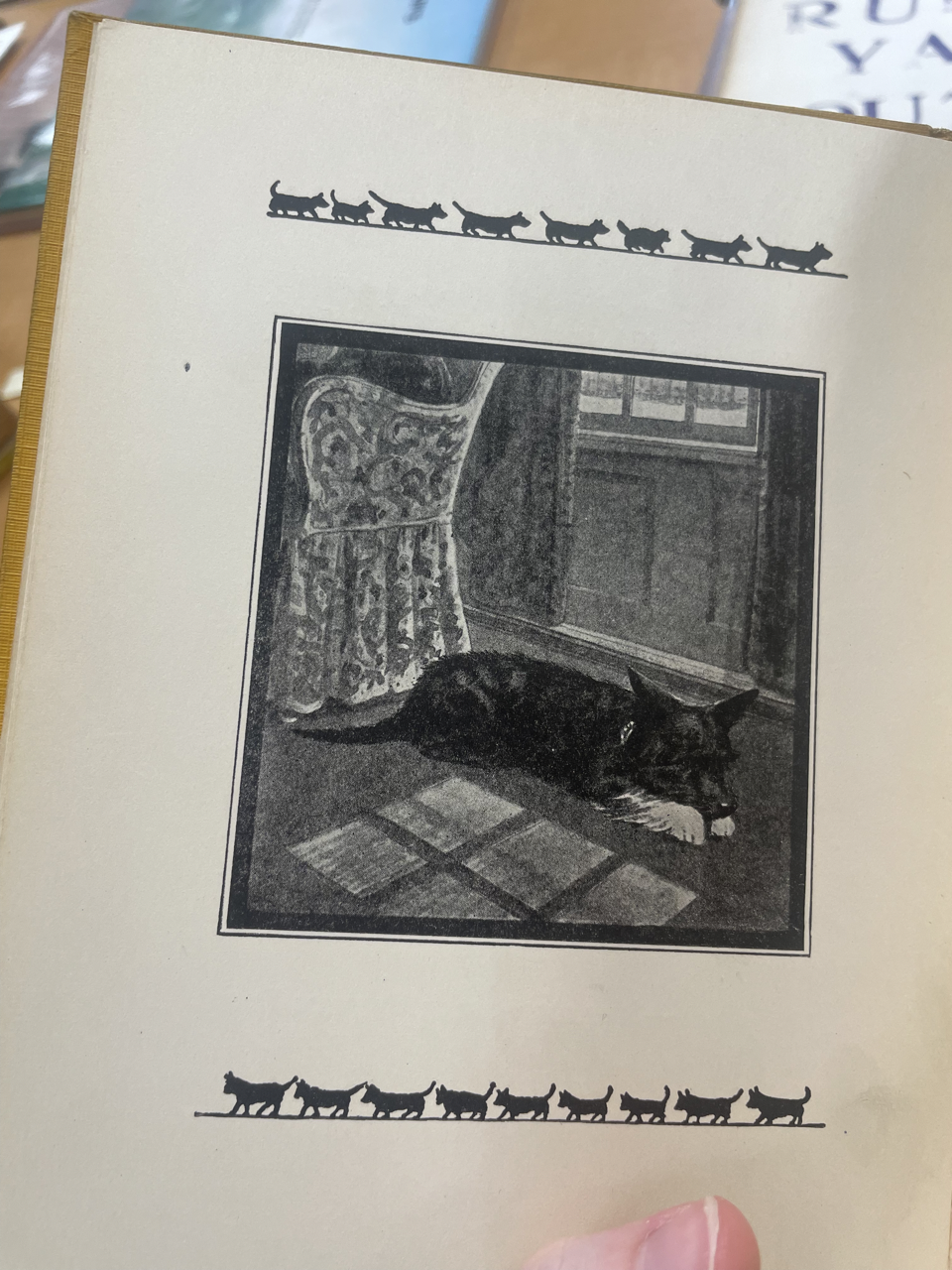

The setting of the Scottish terrier also shows how this edition is an example of cultural appropriation. It is made clear in Figure 3 that the poem’s setting is in an upper-middle-class 1920s home. In Figure 3, there is a plush cushion chair typical of the Roaring Twenties in the upper class, hinting at the owner’s wealth, which is further supported by the maid’s appearance in Figure 1. This is important because it diminishes Rubáiyát’s anti-materialistic message. The original poem argued against material wealth and encouraged readers to find joy in the simpler things in life. This edition decimated this message through the drawings and casual mentions of wealth. The Scottish Terrier is in a nice home with maids and cooks. The dog also wears a flashy, expensive collar as shown in Figure 3. This dog isn’t living a modest, humble life, as originally encouraged in the Rubáiyát. This edition doesn’t honor and appreciate the Rubáiyát and its message and cultural significance.

This edition simultaneously capitalizes on the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam’s culture by mimicking its language and erasing the Persian influence by creating a uniquely Western-centric setting. In writing this edition, Sewell does engage in cultural appropriation because he uses a Persian poem as a foundation and then covers his tracks by erasing all Persian influence and the authentic meaning to the target audience, children, by drawing a Scottish terrier living in an upper-middle-class, white, Roaring Twenties home.

Sources cited:

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. University Press of Virginia, 2000.

FitzGerald, Edward. Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Oxford University Press, 2010.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. "What Is Cultural Appropriation?". Encyclopedia Britannica, 7 Dec. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/story/what-is-cultural-appropriation. Accessed 1 May 2025.