In the book titled On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, author Barbara J. Black examines the Victorian museum culture, and its power in collecting and exhibiting. Black asserts that “the collection and preservation of the Rubáiyát demonstrate one culture’s hegemony over another” (58). Because of this, it is strongly articulated in her piece that FitzGerald’s Rubáiyat of Omar Khayyám was appropriated first by FitzGerald himself as well as the audiences and publishers in decades to follow. The growing popularity of the Rubáiyát as a gift giving book made the poem’s value become “inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness” (61). The book became categorically Oriental when its popular consumption was due to its status as a treasure rather than its original political and cultural workings.

Although the Rubáiyat of Omar Khayyám published by Dodge Publishing Company in 1916 is distinguished by its simplicity and lack of intricacies, this version can still attest to Black’s argument. Marked on the light tan cloth cover is the title of the book stamped with a decorative gold gilt (see Figure 1). The decorative font and the embellished grapes and leaves below the title constitutes the book as a beautifully crafted treasure. Originally, the purpose of a book cover was to function as a protective device that kept pages together with binding. The aesthetic element was to be a decorative tribute to the cultural authority that a book possessed. Cover images, from symbols to ornate fonts, draws the readers’ attention in and tells the story of the book without them turning its pages thus amplifying the message it communicates. On this edition the large stem grapes works as a central symbol that appears throughout the Rubáiyát representing wine, life, and merriment. This could have potentially garnered a lot of attention and “compelling curiosity” (60) from Western readers.

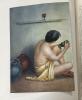

Furthermore, the Rubáiyat – while some argue is not necessarily an Orientalist poem – prompted an Orientalist response in illustrations and photography. In the 1916 Dodge publishing edition, there is photo-poetry throughout the book that is captured by artist Adelaide Hanscom Leeson. The Bloomsbury Collections defines photo-poetry as a “form of photo-text that takes, for its primary components, poetry and photography.” In other words, it is an art form that combines poems and photographs to create a symbiotic relationship between the photo and the text. Hanscom Leeson attempted to translate FitzGerald’s literary vision into a photographic one with a certain aesthetic that is gleaned from his symbolism. In this edition, the photographs are vibrant and appear as painting-like illustrations. The specific images are placed on subsequent pages adjacent to the quatrains that they are connected to. Illuminated in the art work is Orientalism which could be seen in the style of imagery and thought used to depict the Middle East. Through conscious posing, elaborate costumes, and symbolic props, Hanscom Leeson’s artwork attempts to depict the metaphors in the quatrains but also the fascinations of the Eastern World through a Western lens. Barbara Black brings this to light when she refers to the translation and transference of metaphors as Oriental drag or “dressing the Englishman in Persian costume” (63). In the illustration that appears on the first page of this edition, there is a model kneeling with a cloth covering his lower half while one hand is raised holding a cup (see Figure 2). This alludes to quatrain LXII, “I must abjure the Balm of Life to fill the Cup,” as well as other quatrains that reference filling and pouring cups. Similarly, in another photograph a woman wearing a long cloak and a beaded headband holds up a cup (See Figure 3). A common thread in this photograph among others is that the models enact physical actions and gestures. Despite these allusions and textualized metaphors, Hanscom Lee’s photographs for the Rubáiyát are stylized to be exoticized and visually enticing to the audience which does contribute to the poem’s objectification. Some can argue that the photographs reduce the poem’s historical and cultural context while attempting to represent the Orient.

Work Cited:

Black, Barbara J.. On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums. United Kingdom, University Press of Virginia, 2000.

Nott, M. (2018). Introduction: Photopoetry: Forms, Theories, Practices. In Photopoetry 1845–2015, a Critical History (pp. 1–18). New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/book/photopoetry-1845-2015-a-critical-history/introduction