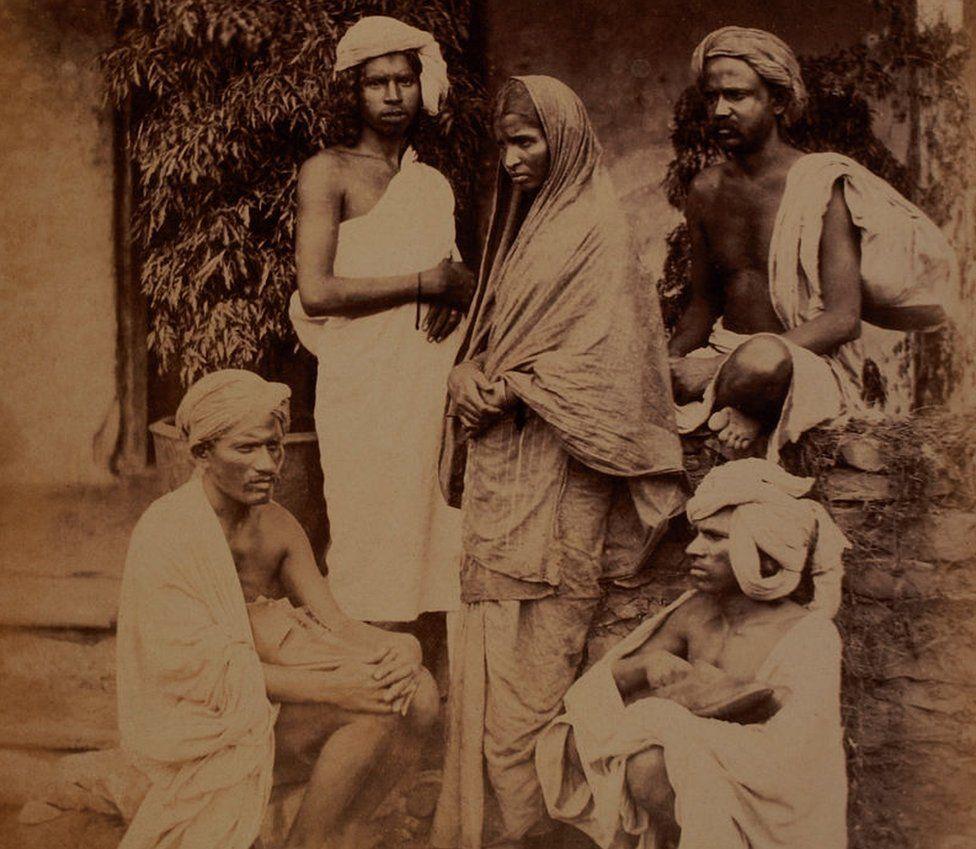

This image is of members of the Scheduled Caste, which included the Hari.

Early in her text, Sen writes about how her mother largely rejected her because she was not a boy and instead Sen “was given over to an untouchable woman of the Hari caste who I called Punti-ma. She used to feed her daughter (older than me by one month) at one breast, and me at the other” (Sen 9-10). The history and complexity of the caste system in India has been consistently reduced due to the British Indian government’s classification of the castes in terms of a four-tiered hierarchy with “untouchables,” including the Hari subset, at the bottom. British imperialism led to an entrenchment of categories which were more flexible in the pre-colonial period. Sen’s description of her upbringing indicates both the presence of caste in daily life but also the interaction among castes as she was part of the Brahman caste yet nursed at the breast of a Hari woman.

Caste was not only defined by occupation, with “untouchables” often serving in manual labor roles, but also contained regional nuances. For example, the Hari caste was specific to the Bengal region.

While Ghandi used the term Harijan, meaning “Children of God,” to advocate for the members of the lowest caste, this term is now considered demeaning and offensive and has been replaced with the official name “Scheduled Class,” though the words “Dalit” and “untouchable” continue to be used colloquially. The official name originated from the Government of India Act of 1935, which listed the lowest caste in a separate schedule from the rest. Recognizing both the importance of and the fluidity within the caste system is crucial to understanding the constant evolution of Sen’s social status throughout her life.

Sources: