Helen Allingham (née Paterson) was born on September 26th, 1848 to Alexander Paterson, M.D., and Mary Herford in Derbyshire, England as the oldest of seven children. After the passing of her father in 1862 to a diphtheria epidemic when Allingham was thirteen years old, the family moved to Birmingham (Clayton 1). She had expressed an interest in art from an early age after exposure to it from her maternal grandmother and aunt, both of whom were accomplished artists in both oils and watercolors (Clayton 2). In fact, her aunt, Laura Herford, was the first woman ever admitted to the Royal Academy School for arts education and helped break the narrative that women required less formal art education compared to men (Zimmerman 109). And so, Allingham pursued art and took courses of study at the Birmingham School of Design where she worked three days a week (Clayton 2). After her success at this school, she was enrolled at the Royal Academy School in 1867 where she took the usual courses of study and learned how to paint with oils but found herself gravitating towards watercolors (Clayton 4).

As she continued her studies there, she returned to London and found work as an illustrator for Once a Week magazine and creating artwork for children’s books. A later job she picked up alongside her studies was illustrating for the serial stories in Aunt Judy’s Magazine. After she finished her studies at the Royal Academy, she became a full-time staffer for the magazine Graphic. During her time working there, her talents began to get noticed because of the excellent composition of her illustrations (Clayton 5). But throughout all this, when she was not producing artworks for books or magazines, she was beginning to create watercolor pieces on the side. It was after her marriage to William Allingham in 1874 that she switched her focus from illustrations to exclusively watercolor paintings, and thus jumpstarted her path to artistic renown (Clayton 5).

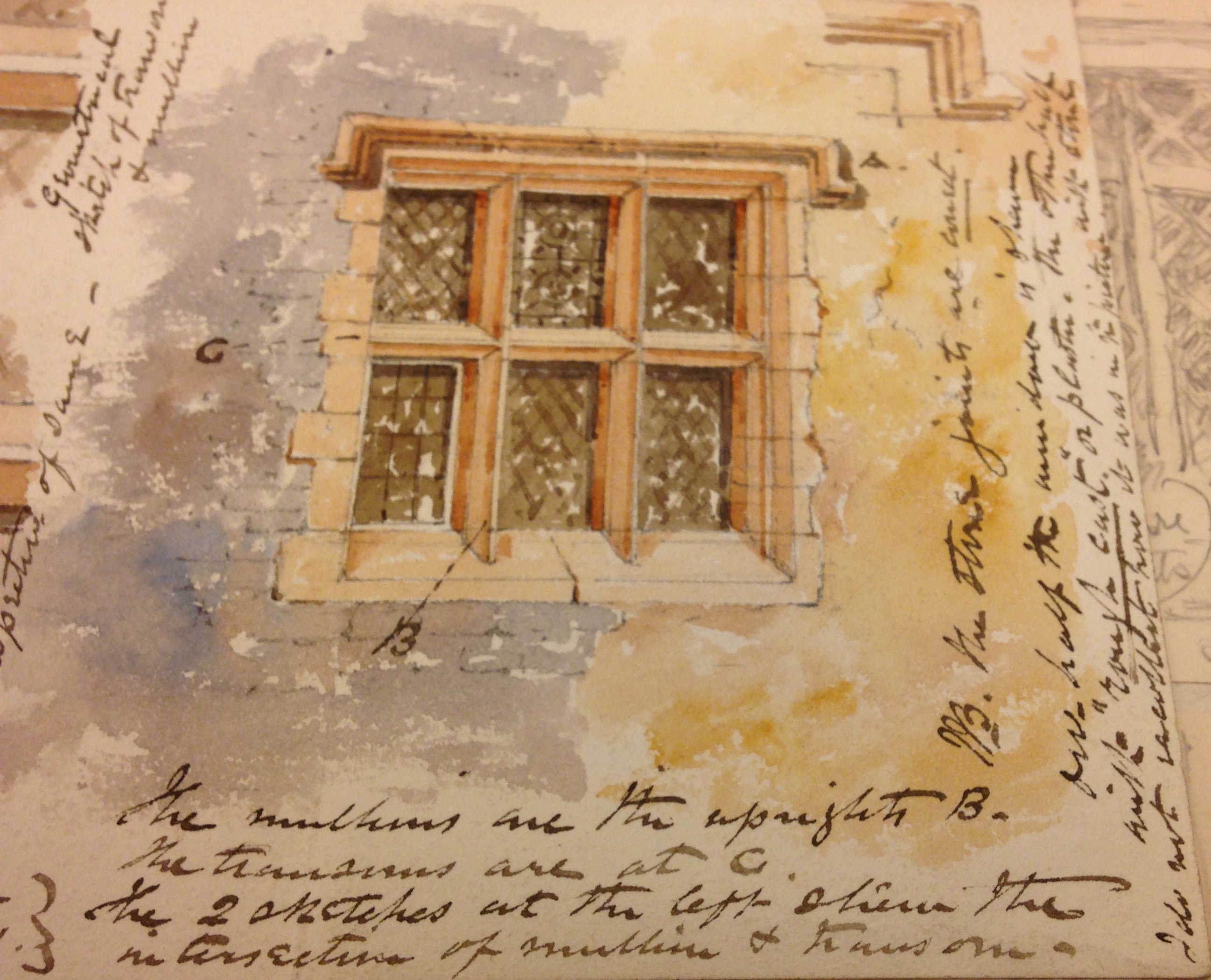

Sketch of a cottage window by Helen Allingham (year unknown), via Duke University Library

Helen Allingham’s rise to notoriety as an artist came at a time when there was an increase in professional artists and art education following the creation of many art schools (Devereux 1). She would become best known for the watercolor paintings of cottages that she produced during the 1880s through the turn of the century, though she made many in the 1870s as well. These landscape watercolor paintings exemplify an idealized representation of the southern English countryside and almost exclusively featured women and children. At their core, these watercolor paintings were meant to invoke a sense of nostalgia for a lost, golden age of England through the use of vibrant colors to create domesticity in the landscape (Devereux 109).

Watercolors as a medium for painting became more common alongside the increase in professional artists since watercolor paints were the last of the traditional media to emerge at the end of the 18th century (Parks 30). They became more popular because watercolors were useful for fast, on-the-spot sketching. Unlike other paints and means for art creation, watercolors allowed for new kinds of expression as the art world underwent several art movements and styles transformed rapidly (Parks 31). These paints also allowed for free-flowing techniques, washes, transparencies, and sensitivity of touch—all of which were hard to achieve with other paints (Parks 32). However, it was because of this view of watercolors being an “easier medium” that they were deemed “feminine” and regarded as daintier and delicate compared to other paints, such as oils. This view is also due in part to how watercolor artworks were created. To use watercolors, an artist could be seated anywhere there was ample light, so special art studios for the artist to stand and work in were not needed (Devereux 111). This also meant the method of painting en plein air (or painting outdoors) was no longer needed, though Allingham chose to do so anyway unlike other watercolorists during her time (Devereux 112).

Another way she was unique from other watercolorists and artists of her time was in the subject of her paintings; Helen Allingham focused less on ambitious, non-historical subjects. Her watercolor paintings were often confined to picturesque sceneries such as cottages, small fields, meadows, and rural roadways (Devereux 113). These works, centric around domestic peace and contentment, became some of her most popular and influential works, especially with her attention to detail and intense color schemes. Even today, her watercolor paintings featuring cottages are used to understand the old architecture of English cottages because of their detailing (Devereux 114). This was in great contrast to the expectation of the time for women to create art that was beautiful but not essential because of their less formal art education (Zimmerman 110).

"The Young Customers" by Helen Allingham (1875), via The Helen Allingham Society

In 1875, Allingham was elected to be an Associate of the Society of Painters in Water Colors because of her talent with watercolors, and in that same year, she produced one of her most notable watercolor pieces titled “The Young Customers" (pictured above), which leading critic of the Victorian era, John Ruskin, described as “old-fashioned as red-tipped daisies and more precious than rubies” (Clayton 5). She would go on to be a member of other art societies, including the Royal Watercolor Society in 1890 where she became the first woman to be elected to it as a full member. She also would have her works exhibited in the 1893 World’s Colombian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois at the Palace of Fine Arts (Clayton 5).

Works Cited

Clayton, Ellen C. English Female Artists, Volume II. London, Tinsley Brothers, 1876.

Devereux, Jo. The Making of Women Artists in Victorian England: The Education and Careers of Six Professionals. McFarland, Publishers, 2016.

Parks, John A. “The Masterful Use of Watercolor Throughout History.” American Artist: Watercolor, vol. 17, no. 68, 2011, pp. 30-37. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aft&AN=65267899&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Zimmerman, Enid. “Art Education for Women in England from 1890-1910 as Reflected in the Victorian Periodical Press and Current Feminist Histories of Art Education.” Studies in Art Education, vol. 32, no. 2, 1991, pp. 105–116. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1320282.

Image Attributions

Photograph of Helen Allingham (1903), via The Helen Allingham Society

Sketch of a cottage window by Helen Allingham (year unknown), via Duke University Library

"The Young Customers" by Helen Allingham (1875), via The Helen Allingham Society