In 1941, Pocket Books Inc. released a mass-market paperback edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, bringing Edward FitzGerald’s Victorian translation of the Persian quatrains into the hands of a broader American readership. While FitzGerald’s poetic renderings had enjoyed a long-standing popularity among the literary elite, this edition reflected a cultural shift: the democratization of literature in the early 20th century.

To understand just how significant the price of a book was in the early 1940s, consider this: in 1939, a gallon of gasoline cost 19 cents (U.S. Department of Energy); a dozen eggs averaged 16.3 cents (U.S. Department of Labor 36); and a loaf of bread in 1940 was averaged at 5.59 cents—“well above the average” of the previous decade (U.S. Department of Labor 23). By contrast, a listing for a first edition hardcover of The Grapes of Wrath shows a price of $2.75 printed inside the book (Steinbeck). In practical terms, that single book cost the equivalent of roughly 49 loaves of bread or over 14 dozen eggs—an amount that, while difficult to calculate precisely, may have matched the cost of a week’s groceries for many households. Book ownership, then, was not a casual affair. It was a luxury, and literature was often reserved for those who could afford to spend extravagantly on a single volume.

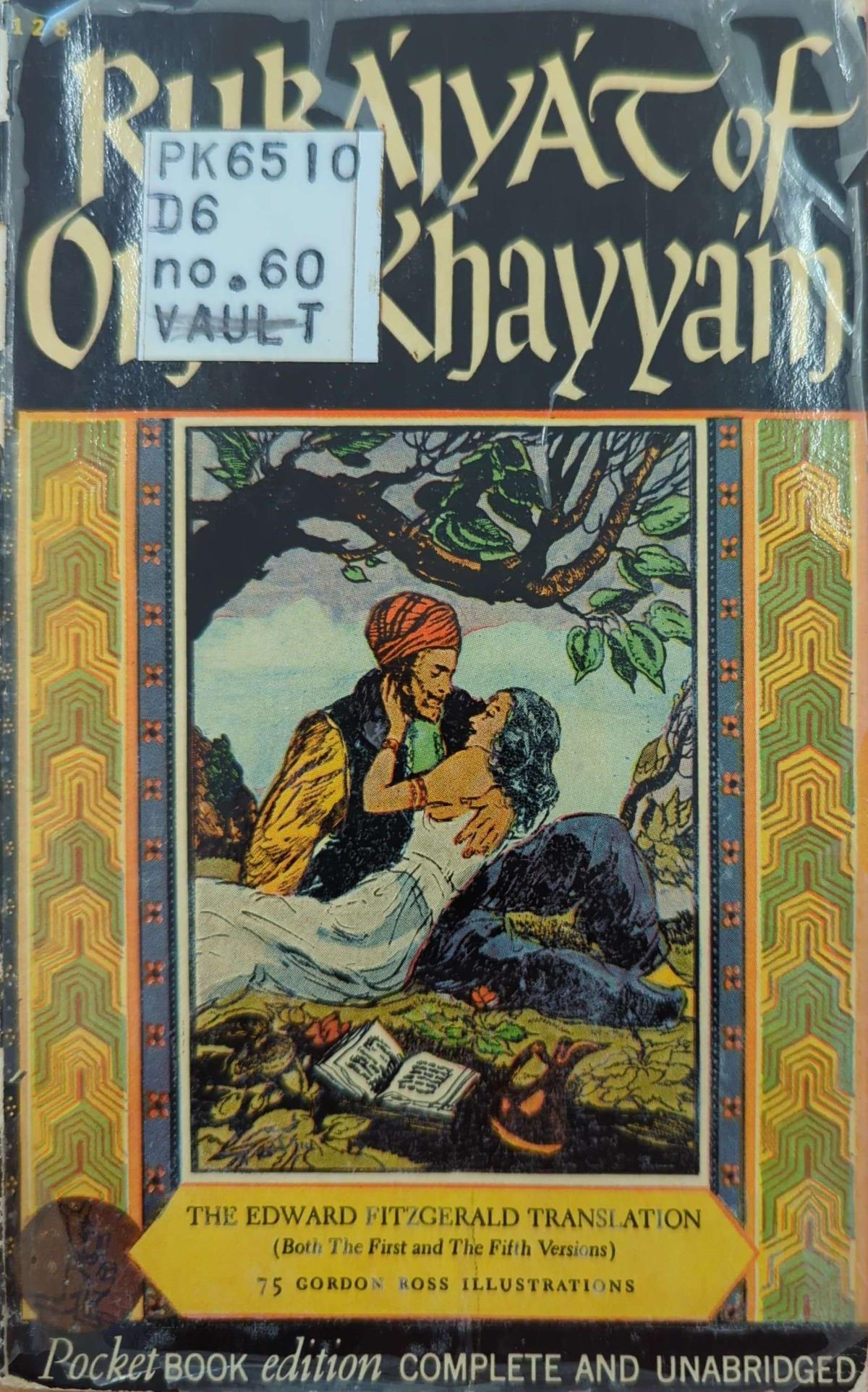

This context makes the founding of Pocket Books in 1939 especially notable. The company was launched by Robert F. de Graff, who believed that “the public would buy cheap, paperbound books if, through adequate distribution, the books were brought to them” (“Robert F. de Graff Dies”). With this vision in mind, de Graff secured financial backing from Richard L. Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster of the publishing house Simon & Schuster. Modeled in part after Penguin Books in the UK—established in 1935 by Allen Lane to offer “quality, attractive books affordable enough to be ‘bought as easily and casually as a packet of cigarettes’” ("Our Story – Timeline")—Pocket Books brought this ethos to American publishing. Their low-cost, priced at 25 cents (Figure 1), mass-market editions transformed literary accessibility during a time when entertainment options—such as movie tickets at 23 cents in 1939—were still far more affordable than books (Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta). Their editions featured glued binding, colorful covers, and a convenient size designed to fit in a coat pocket or purse, wrapped in “parma-gloss” a film meant to keep them safe and durable(figure 2 &3), and the iconic kangaroo logo; these books not only made literature portable and affordable, but also helped define a new reading culture during wartime and the Great Depression.

The Pocket Book edition of the Rubáiyát fits neatly into this legacy. Its compact format and elegant design allowed it to straddle both literary tradition and mass accessibility. While many 19th-century editions of the Rubáiyát were lavishly illustrated and bound in ornate covers to serve as gift books, this 1941 version was a more practical object, emblematic of a modern sensibility that prized portability without entirely sacrificing aesthetic appeal.

The edition’s illustrations were created by Gordon Ross, a prolific but somewhat elusive figure in early 20th-century illustration. Despite his name appearing in this edition of the Rubáiyát, verifiable information about Ross’s life and career remains scarce. One privately maintained archive, part of a larger digital project on the history of the Rubáiyát, is dedicated to documenting his contributions, though it does not cite its sources (Forrest). Nevertheless, Ross’s work for Pocket Books appears visually indebted to the decorative styles of earlier illustrators such as Edmund Dulac and Willy Pogány, whose lush and evocative imagery helped define the poem’s aesthetic legacy.

This edition not only brought FitzGerald’s poetics to a broad American public, but also testified to a growing cultural belief that literature should be accessible to everyone—not just the elite. The innovations of Robert F. de Graff and Allen Lane were based on a shared premise: people wanted to read. What had stood in the way was not apathy, but affordability. De Graff insisted that Americans would eagerly buy books if they were priced reasonably and widely available—and the popularity of Pocket Books proved him right. The 1941 Rubáiyát thus reflects not just a publisher’s vision, but a national desire to engage with literature more fully. The Rubáiyát, in this moment, was no longer a luxurious gift book bound in leather, but a tool for reflection in a time of crisis.

Work Cited

Ennis, Thomas W. “Robert F. de Graff Dies at 86; Was Pocket Books Founder.” The New York Times, 3 Nov. 1981, https://www.nytimes.com/1981/11/03/obituaries/robert-f-de-graff-dies-at-....

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. “Real versus Nominal Values: Let’s Go to the Movies!,” https://www.atlantafed.org/-/media/documents/education/teach/lessons-and....

Forrest, Bob. "The Rubaiyat of Gordon Ross," https://www.bobforrestweb.co.uk/The_Rubaiyat/N_and_Q/Index.htm. Accessed 23 May 2025.

Penguin Books. “Our Story – Timeline.” Penguin Random House, https://www.penguin.com/our-story-timeline/.

Steinbeck, John. The Grapes of Wrath. Viking Press, 1939. Listing on AbeBooks, https://www.abebooks.com/first-edition/Grapes-Wrath-Steinbeck-John-Vikin.... Accessed 23 May 2025.

U.S. Department of Energy. “Fact #741: August 20, 2012 - Historical Gasoline Prices, 1929–2011.” Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, https://www.energy.gov/eere/vehicles/fact-741-august-20-2012-historical-....

U.S. Department of Labor. “Wartime Prices,” 1913 to December 1943. Bulletin No. 749, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1944. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/bls/bls_0749_1944.pdf.

University of North Carolina Libraries. “Teaching Paperbacks.” UNC Library Exhibits, https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/teachingpaperbacks/history.