In Quatrain 10 of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, the stanza stages a fantasy of escape from hierarchy in a verdant haven beyond the desert. However, the accompanying image by Gordon Ross operates within a racist and Orientalist framework, depicting the Middle East as backward, barbaric, and brutal. In doing so, the image undermines the stanza’s utopian vision it seeks to produce, ultimately reinforcing systems of hierarchy and segregation rather than imagining their dissolution.

The language of Quatrain X imagines a thin, fragile paradise where the rigid hierarchies of society momentarily dissolve, offering a fantasy outside the divisions of slave and sultan. The first line evokes a narrow, delicate band of growth, described as a “Strip of Herbage strown, ”between two immense forces: the barren desert and the cultivated, controlled land. This small strip "just divides the Desert from the Sown," resisting both the lifeless chaos of the wilderness and the domination of human civilization. It is a liminal space—neither fully barren nor fully controlled—where life persists without submission to either extreme. It is within this small strip of land, upon which the speaker has invited us to, “walk with [him],” where oppressive titles that structure human existence fall away. As the speaker notes, it's a place where the “name[s] of Slave and Sultan scarce [are] known," suggesting that either slave or sultan exists here equally. By inviting us to walk with him, the speaker asks us to imagine this fragile paradise—a vision of egalitarian life where hierarchies dissolve and domination gives way to a vital, precarious, freedom. The stanza closes with a gesture of sympathy: "And pity Sultan Mahmud on his Throne," footnoted in this edition referring to the historical conqueror whose empire encompassed present-day Afghanistan. From the vantage of this fragile, in-between paradise, even an emperor who once ruled vast territories is seen not as enviable, but as pitiable—trapped by the very structures of conquest and domination he once embodied.

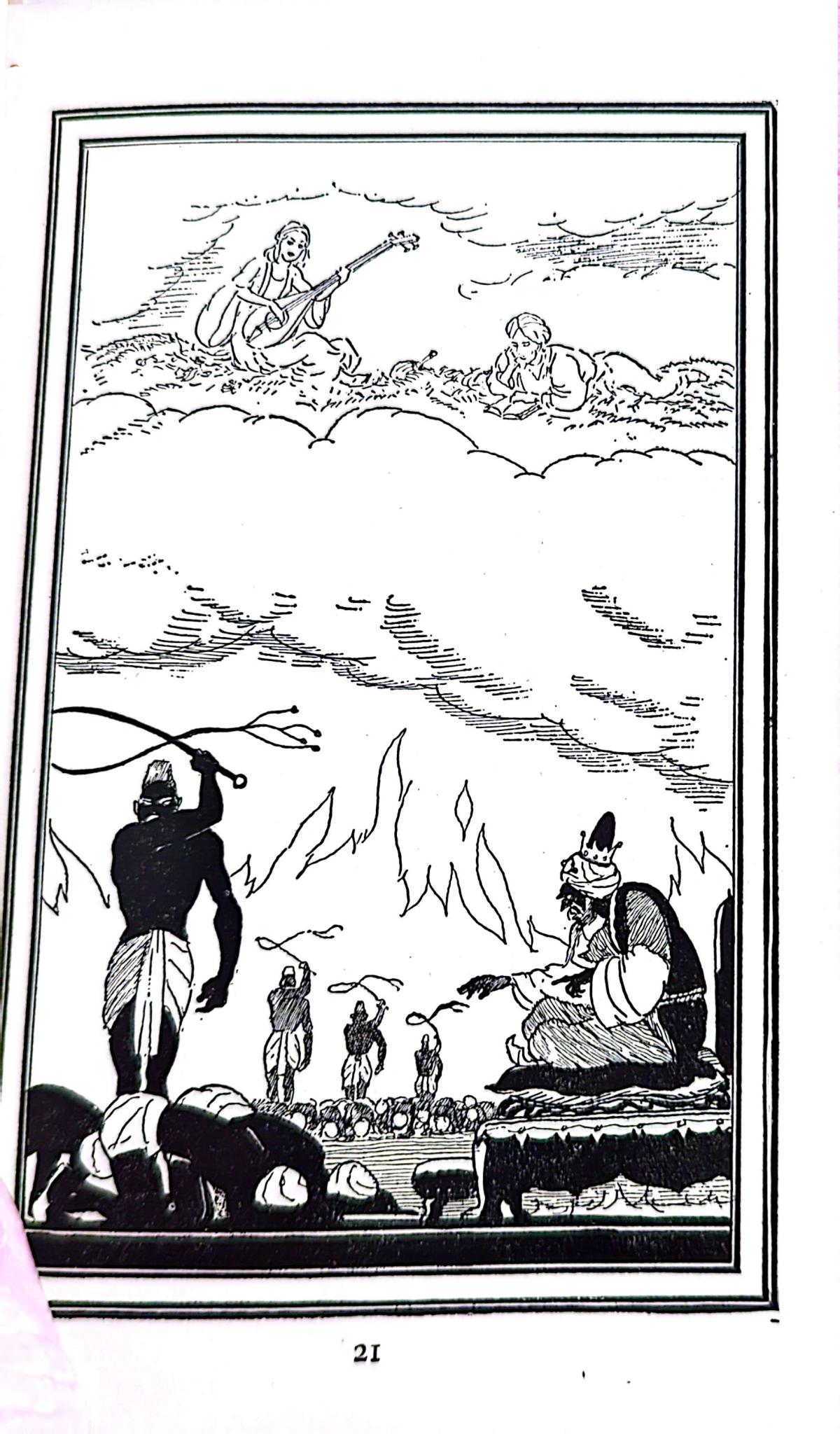

The accompanying image undermines the stanza’s utopian vision by depicting the Middle East not as a space of fragile freedom, but as one of racialized violence and domination. In the lower half of the accompanying image (figure 2), a Black-skinned sultan sits on a throne while three Black-skinned slaves bow before him, their bodies fully prostrate. Above them, a taskmaster, mid-whip, towers over their backs, the lash about to fall upon their bare skin. Behind them, the scene repeats; rows of slaves lay prostrate, waiting for the lash of the taskmasters--an endless chain of submission and punishment. The background blazed with jagged shapes, evoking fire, evoking that this space is a hell--one defined by barbarity, domination, and violence.

The upper half of the illustration makes explicit the racial and Orientalist dichotomy embedded in the image. Floating above the fire and domination below is a soft, fluffy cloudscape, its texture forming into long grass. Resting atop this idyllic space are two white-skinned figures: a man lying on his stomach, reading a book, and a woman seated upright, playing what appears to be a laouto. Between them sits a bottle of wine, visually alluding to the well-known Quatrain 11: “A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse—and Thou.” Their posture is casual, peaceful, and joyful, this is in stark contrast to the violent submission below. As such, this upper space presents whiteness as the domain of culture, leisure, literacy, and refined pleasure. Paradise, the image suggests, does not lie in the fragile, liminal space between domination and barrenness that the stanza imagines—but rather in a rigid racial hierarchy that positions whiteness as elevated, cultured, and detached, hovering above the brutal world of the racialized East.

The image collapses the desert and the dominated land into a singular hellscape of Orientalized suffering, while reserving peace and paradise for those above. In this dichotomy, there is no-inbetween; no herbage strip. The egalitarian paradise depicted in stanza dissolves into a stark visual reinforcement of racist and orientalist divisions. In this constructed juxtaposition, paradise is not a liminal refuge from hierarchy but a racialized ideal: paradise is whiteness—cultured, detached, and elevated above the suffering of others. The image does not visualize the stanza’s dream of freedom; it reinstates and naturalizes a rigid civilizational divide, reinscribing the very hierarchies the poem seeks to transcend.