Jekyll/Hyde in Ink

Introduction:

Illustration provides a means of depicting things that cannot be depicted in real life, and even in films without the use of special effects and intensive editing. The monstrous has been a particular well of inspiration for visual artists because there is so much potential for the imagination to envision the unreal. Before special effects editing techniques in films, ink illustrations could depict the transformations between Jekyll and Hyde, or the combination of the two sides together, without jarring spliced edits or jump cuts. They can also go beyond what can be done with makeup and props to depict the fully uncanny. As one source notes, “[Victorian novel] illustrations offer clear precursors of film editing” (Elliott 97). Due to the fact that Stevenson’s original text does not include precise descriptions of Hyde (other than his size relative to Jekyll), it is also a relevant point of study to analyze how illustrators use their skills to visualize a monster. Inherently, adaptations into new visual media result in varied and contradictory depictions, because of the vagueness within the source text. One scholarly text makes the argument that Gothic novels have “multiple interpretations [that] are embedded in the text and part of the experience of horror comes from the realization that meaning itself runs riot. Gothic novels produce a symbol for this interpretive mayhem in the body of the monster. The monster always becomes a primary focus of interpretation and its monstrosity seems available for any number of meanings” (Halberstam 128). With this looseness of meaning comes a freedom in artistic creation. Hyde can be shaped into whatever the illustrator determines is most threatening. In some cases, this involves Jekyll as a target for Hyde, or the two may be equally monstrous as inseparable counterparts of each other. In these images, Hyde is represented as monstrous and/or threatening in various ways. The purpose of this gallery is to answer with four examples the question “How have illustrators interpreted the relationship between Jekyll and Hyde visually and artistically?”

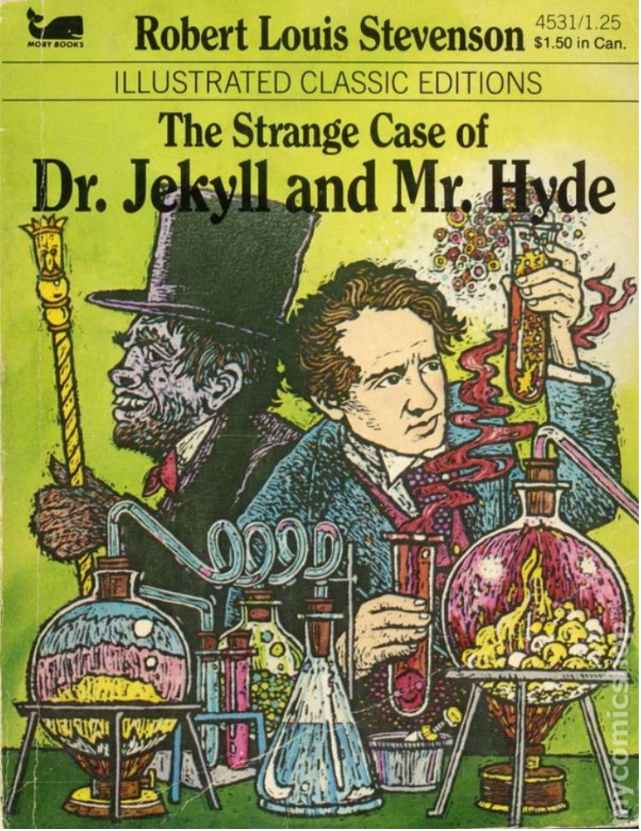

Yamamoto, Mitsu. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Yamamoto and Robert Louis Stevenson, Moby Books, Illustrated Classic Editions, 1977.

This book cover depicts Jekyll and Hyde as distinct people in distinct bodies. The bright colors of Jekyll and his lab materials are contrasted to the relatively monochrome Hyde behind him, making Hyde appear almost as Jekyll’s shadow. In addition, while Jekyll looks at the vial in his hand, away from Hyde, Hyde stares at Jekyll out of the corner of his eye. This image makes a contrast between Jekyll and Hyde as a way to depict Hyde as threatening and predatory. It plays a little into the ape-man trope, because Hyde has more body hair, jagged teeth in a devilish grimace, and an upturned nose with larger nostrils. This makes him resemble an animal or monster more than a human. As Jekyll admits, speaking of his two selves, “Even as good shone upon the countenance of the one, evil was written broadly and plainly on the face of the other” (Stevenson). The baser, more evil, and less human Hyde is a stark contrast to the scientifically curious, normal-looking Jekyll. Jekyll further explains the theory he has for why Hyde appears less “developed”: “The evil side of my nature…was less robust and less developed…it had been much less exercised and much less exhausted” (Stevenson). This illustrator has chosen to depict this lack of development as atavistic and threatening to Jekyll. At the same time, Jekyll is shown doing the experiment that will manifest Hyde. While they are in distinct bodies, the bodies overlap in the image, which draws an inextricable connection between them. Hyde will come out of Jekyll, like a shadow, and like a shadow he will follow Jekyll wherever he goes. This illustrator has made Hyde and Jekyll distinct and connected through contrast, placement, and visual cues to the monstrous/atavistic. They appear to be inseparably linked even as they are so visually different.

Cameron, Lou. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Cameron and Robert Louis Stevenson, Classics Illustrated Comics, no. 33, 2015.

The second book cover shows a Hyde completely detached from Jekyll. Again, Hyde stares at Jekyll as Jekyll gazes into the vial that will turn him into Hyde. Colors are similarly used to contrast the two men; this decapitated Hyde is green and comes out of the fumes of the mixture in Jekyll’s hand, which visually links Hyde to the substance that creates him, and the man responsible for this substance. At the same time, it makes Hyde look less human, even though this depiction is not especially monstrous. Stevenson’s text more explicitly corroborates this kind of depiction of Hyde. Jekyll explains, “I have observed that when I wore the semblance of Edward Hyde, none could come near to me at first without a visible misgiving of the flesh. This, as I take it, was because…Edward Hyde, alone in the ranks of mankind, was pure evil” (Stevenson). The people who encounter Hyde cannot point to a specific thing about him that is wrong with him–he just appears to be bad in an essential way. This Hyde appears human, but his greenness makes it clear that there is something a little bit off about him, something that sets him apart from everyone else. His expression is ominous and disapproving. He frowns down at his counterpart, who is on the whole respectable-looking and visually unremarkable. This illustrator has depicted the relationship between Jekyll and Hyde to be less equal in several ways. First, Jekyll takes up more space, and the harsh lighting on his face makes it the focal point of the image. As we see that Jekyll is looking at the vial, our eyes follow his. But although Hyde is visually smaller–a smoky head without a body–his fluorescent color, his expression, and his placement slightly above Jekyll grant him presence and power. Jekyll’s face is vaguely grim; Hyde’s is focused and foreboding. Between the two of them, it appears Hyde is the one in control, even as Jekyll alone holds the vial.

Sullivan, Edmund Joseph. Jekyll and Hyde story illustration. 1928. Science Photo Library, British Library, https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/530155/view.

This early artwork clearly testifies to the unique capabilities of illustration as a medium. As one transforms into the other, Jekyll and Hyde are fused down the middle mid-transformation, and each side has distinct posture, shading, body shape, facial features, and expression. Even the inked lighting falls on the halves differently. Jekyll, on the left, wears a clear forward gaze and neutral expression, with respectable appearance and a more open stance. On the right, Hyde stands hunched and drawn into himself; even his face is closely drawn toward its center, with a smaller, higher nose, an arched brow, and a snarl. While hunching, Hyde is still a giant compared to Jekyll, and his slouch is the only thing keeping his head level with its other half. The tight stretches across his half of the clothing that both wear also attests to his gigantism. Although Hyde’s size here is exactly counter to how it’s described in Stevenson’s text, it adds to his image of baseness. His slouch and drawn-in face signify his darker, twisted personality and lower status. But despite all the differences between them, Hyde and Jekyll remain bonded visually and literally within the frame. The shading across both sides of the jacket is the same, and both hands perform the same gesture. Jekyll’s hand reaches into Hyde’s half of the frame, where the darker shading on the fingers makes it indiscernible whether they are Jekyll’s or Hyde’s. This implies a smooth transition between the two men–an inherent connection rather than a distinction. Jekyll says of himself and Hyde: “I saw that, of the two natures that contended in the field of my consciousness, even if I could rightly be said to be either, it was only because I was radically both” (Stevenson). This illustrator has interpreted this idea into a perfect split between Jekyll and Hyde. The relationship here is one of inseparable similarities and differences. The drawing shows that while both sides appear to contain a separate man, each shares something with the other that fuses them together, that draws them closer to being a single person.

Beaman, Sydney George Hulme. Jekyll and Hyde story illustration. 1930. Science Photo Library, British Library, https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/530157/view.

Here is another illustration of Jekyll/Hyde mid-transformation. It is not clear which direction the transformation is going, because both men are simultaneously dropping the glass that only one of them has just drunk. Hyde is distinguishable from Jekyll only because of his smaller figure and his more ragged hair and face. Otherwise the two appear quite similar, standing in the same shape with the same expression. Here more than in any of the other images is the relationship between Jekyll and Hyde depicted as one with more similarities than differences. Hyde is not only connected to his counterpart; the two are close to indistinguishable, at least in the early stage of transformation. This interpretation is compounded by the placement of the two men within the frame. Jekyll stands behind and offset from Hyde, so that their figures overlap and reveal their parallel stances. Both of them are semi-translucent, and the pair blends together in parts. Their positioning makes sense for two reasons: first, it shows that there is some physical distance and distinction between them. Second, it simultaneously bonds them, allowing them to interact with themselves at the same time that they interact with each other. Jekyll clutches his own chest, which Hyde copies, but at the same time it appears that Jekyll is clutching too at Hyde’s shoulder. They are simultaneously one person and two. Describing his philosophy of human nature, Jekyll claims: “ I thus drew steadily nearer to that truth, by whose partial discovery I have been doomed to such a dreadful shipwreck: that man is not truly one, but truly two” (Stevenson). His belief is that within himself and other people, there are (at least) two personalities that coexist. Hie entire reasoning for his experiment is to break the two apart, as they do here. In this drawing, the transformed Jekyll/Hyde are still obviously part of each other, and their translucence suggests that neither can be whole when they are separated. This illustration depicts a more equal relationship between Jekyll and Hyde, because they appear to depend on and coincide with each other.

Works Cited

Beaman, Sydney George Hulme. Jekyll and Hyde story illustration. 1930. Science Photo Library, British Library, https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/530157/view.

Cameron, Lou. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Cameron and Robert Louis Stevenson, Classics Illustrated Comics, no. 33, 2015.

Elliott, Kamilla. “Book Illustration as Film.” Rethinking the Novel/Film Debate, Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 96-97.

Halberstam, Judith. “An Introduction to Gothic Monstrosity.” Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Robert Louis Stevenson, edited by Katherine Linehan, W.W. Norton & Co., 2003, pp. 128-131.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. COVE Studio edition, Longman, Green, & Co., 1886. https://studio.covecollective.org/anthologies/fa22-lit-and-film-anthology/documents/stange-case-of-dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde#chapter10

Sullivan, Edmund Joseph. Jekyll and Hyde story illustration. 1928. Science Photo Library, British Library, https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/530155/view.

Yamamoto, Mitsu. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Yamamoto and Robert Louis Stevenson, Moby Books, Illustrated Classic Editions, 1977.