Part One: The Absolute State of Things

Economy: The year preceeding the Morant Bay Rebellion did a number on Jamaica's economy; Britian was pourimg money into The American Civil War rather than sugar and rum, two massive portions of Jamaica's exports. The price of sugar plumeted, sometimes to so extreme a degree that the price was below the actual cost of production. This also increased the price of Jamaica's imports, things like food and clothes. Jamaica was also suffering from severe droughts which, coupled with the low price of sugar, caused many plantations to fail, either financial or in terms of crop production. The result of this was that there were very few jobs for the Jamaican working-class, and because labor was so plentiful wages were very low.

Politics: Slavery had been abolished in 1834, and free men given the right to vote. However, in a blatant disenfranchisement of the Jamaicans, the colonial government required a high poll tax to vote, which most Jamaicans could not afford. In 1864, Edward Eyre is appointed governor. With no choice left but starvation, the working class turned to stealing whatever food was available, for which Eyre enforcced strict punishments like extensive prison sentences and whippings. The number of prisoners triples from roughly 200 to roughly 600 in 1864.

Part Two: Sparks of an Uprising

St, Ann's Petition: The poor working class of St. Ann's Parish petitioned the queen for cheap rent of Crown lands in order to work the land themselves. Eyre sends the petition to the Colonial Office, adding his own comments first: that he believed the description of circumstances greatly exagerated. The head of the West India Department, Henry Taylor, responds to the petition with "The Queen's Advice," a letter which suggests that the Jamaicans should work harder.

October 7th: A Trial: Much of the land previously used for sugar farming had been long abandoned. Farmers would often live on the land and farm it themselves, claiming ownership through actual possession. On October 7th, 1865, one such farmer was brought to trial. a Jamaican Baptist deacon, Paul Bogle, and several folliowers marched peacefully on Morant Bay Courthouse. When one man loudly decried the charges against the farmer and police tried to forcefully remove him from the courthouse, a riot broke out. Two police officers were beaten with sticks and rocks by the crowd, and arrest warrants were put out on the protestors for rioting, resisting arrest, and Police Assault.

Part Three: The Rebellion:

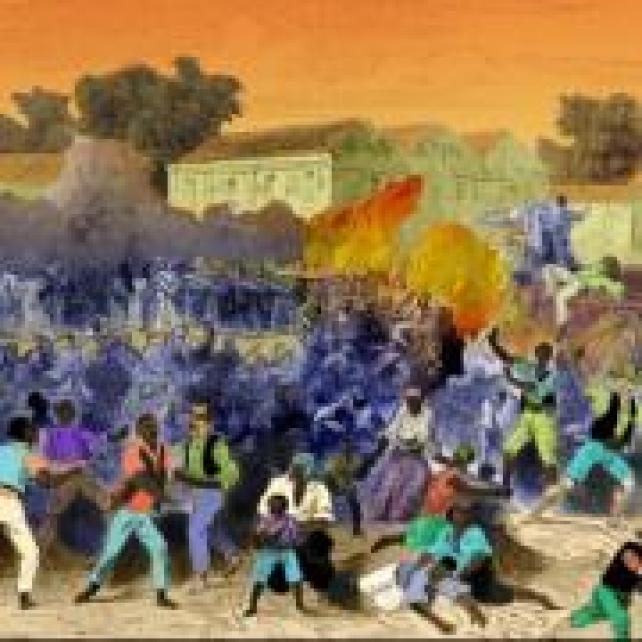

On October 11th, 1865, Bogle again marches on Morant Bay , this time with hundreds of protestors. They are met at Morant Bay by local officials and a small volunteer militia. The protestors attack the militia with sticks and rocks while the militia, in a totally proportioned response, open fire on the crowd of protestors. 25 people die. The protestors burn the courthouse down and the militia retreats. The protestors occupy The Parish of St. Thomas-in-the-East for two days. Eyre sends real troops to the parish. Although the troops are met with no organized resistance, they indescriminately murder close to 4oo innocent Jamaicans, including women and children.

Part Four: The Fourth Part:

Aftermath: Eyre, disbelieving that Jamaicans were capable of planning a rebellion, looks for their supposed leader. He accused George William Gordon, who is biracial. Gordon openly disapproved of Eyre's policies and encouraged the protestors to make their grievances known, but otherwise had little to do with the rebellion. Paul Bogle is also arrested. Both are hanged with no proper trial. Around 350 other Jamaicans are arrested and hanged, also without a fair trial. 600 other Jamaicans are arrested and punished. Soldiers also burned down many homes with no justification. The Jamaica Committe is assembled in December 1865 with the intent of trying Eyre for mass murder. He is not indicted by a jury. After the Morant Bay Rebellion, free people of color are no longer permitted to serve in the Jamaican House of Assembly. Jamaica becomes a Crown Colony.