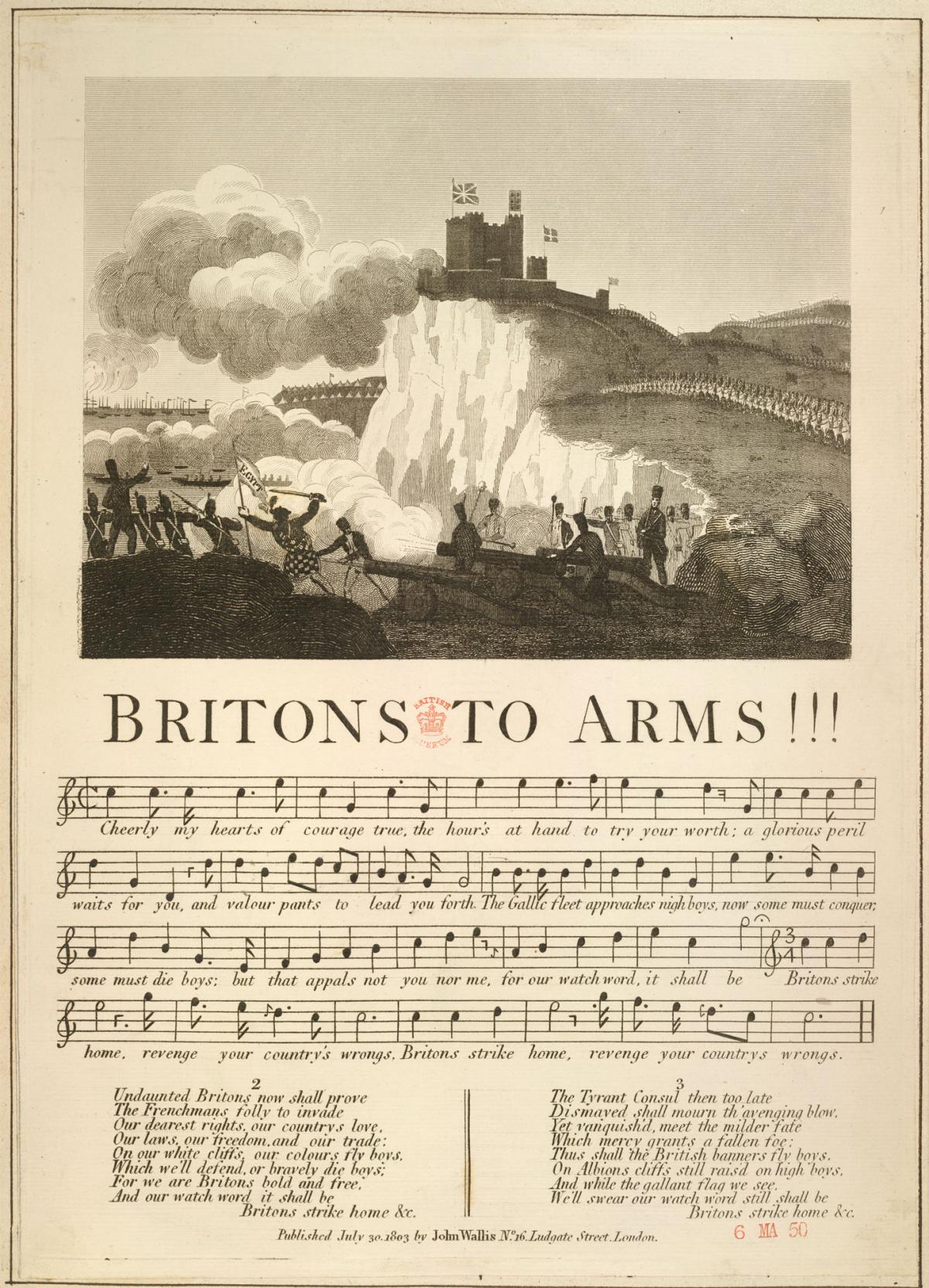

In 1803, Napoleon massed his massive “Army of England” on the shores of Calais, displaying his intentions to invade England. As the hostility between France and England increased with the war, enlistment also increased in size. The fear of invasion contributed to patriotic outbursts and led the public to rally behind the British military. This in turn created a fascination in military men, which fueled its own market in commercial goods such as illustrated books on battle histories, army toys and military-influenced fashions. Peace came shortly after the definitive victory of Waterloo in 1815, contributing to Britain's dominant status in Europe for the next hundred years.

From his autobiography, one cannot tell much about how Mill perceived the threat of war as a young child. There wasn’t any mentioning of the great victory. The war was almost never present in Mill’s text, apart from short references to the peace as a mark in time (56). Nonetheless, the glamorization of the military surely shaped the public’s perception of masculinity in the form of physical vigor. Wartime only strengthened ideas about the communal (public) and the physicality in Victorian middle-class male identities. Mill, by giving a detailed account of his upbringing, was eager to set himself apart from—but equal to—the contemporary young men. Understanding the war’s influence on social norms accentuates the reading of Mill’s claim on the solitary (private) and the mind.

Sources:

1. Mather, Ruth. “The Impact of the Napoleonic Wars in Britain.” Discovering Literature: Romantics & Victorians, The British Library, 15 May 2014, www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-impact-of-the-napoleoni….

2. “The Napoleonic Wars.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/place/United-Kingdom/The-Napoleonic-Wars.