Dante Aligheri (illustrated in Frame 1) was a poet and politician born in 1265 in Florence, Italy. As an Italian born during this time, he was deeply involved in political struggles surrounding the Guelph-Ghibelline conflict, as well as the following conlict between White Guelphs and Black Guelphs. He was a White Guelph and wanted more freedom from the Holy Roman Empire, and when the Black Guelphs took over Florence he was exiled for two years and given a large fine to pay before he would be able to return, as they claimed Dante was corrupt durring his time in office at Florence. He had a great devotion towards his hometown and refused to admit he was guilty of doing it harm, and so he was exiled indefinitely. It was during his exile that he wrote the Divine Comedy, as well as many of his other most famous works. He was an orthodox Catholic, but as a White Guelph he fought for Florence to be a free and independent city-state and was against the influence of the papacy. He was generally quite skeptical of the church, as was somewhat necessary with the politics of the time, but was devout in his love for God.

While Dante produced many great works that have stood the test of time, the Divine Comedy is by far his most famous. It is an epic poem written in Italian in terza rima, a rhyme scheme he invented and was the first to use. The poem is over 14,000 lines long and is spread across three books: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. While Purgatorio is the primary text I want to talk about, the other two books provide necessary context for understanding it properly. The story begins with the first book; that is, Inferno. Dante wakes up in a dark forest and doesn't know where he is, until he is approached by the spirit of the Roman poet Virgil. Virgil explains that he has been given a mission from God to take Dante on a tour of the afterlife, starting with a survey of hell, then moving up Mount Purgatory and finishing in heaven (Dante and Virgil pictured together in Frame 2). As the two explore hell, Dante learns that all who reject God and embrace a life of sin are doomed to eternal suffering under the Earth, away from the light of heaven. The first book yields some rather unusual character development as well; Dante starts off feeling sorrow and pity for the tormented, but gradually comes to understand that this is God's will and the souls fully deserve exactly what they are given. As such, he progressively becomes more cruel and less compassionate towards the spirits of Inferno.

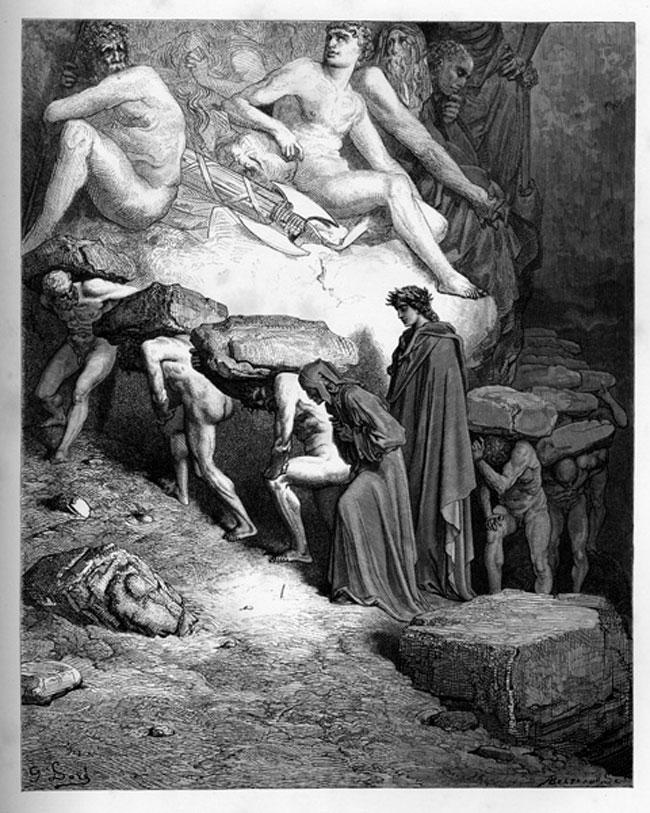

Purgatorio, the second book, takes on a much more hopeful and compassionate tone. Mount Purgatorio is reserved for sinners who were repentant in their lives, even if it was only at the very end. Similar to the circles of hell in Inferno, different terraces of the mountain host a different variety of sinner, and the souls who reside on that terrace are given a punishment befitting their crime (see Frame 3). In the case of Purgatorio, there are seven terraces, each of which punish one of the seven deadly sins and encourage the virtue that is its opposite: pride and humility, envy and gratitude, wrath and patience, sloth and diligence, avarice and charity, gluttony and temperance, lust and chastity. Dante explores them in that order, beginning with sins which promote the love of evil or hate, and finishing with sins that represent an excess of love for earthly goods over heavenly ones. Sloth is right in the middle of the two as it represents an insufficient amount of love in the first place.

Perhaps the most important detail of Mount Purgatory, and what sets it apart most from hell, is that the suffering there is not eternal. Every soul in purgatory is working to shed themselves of their sins and become worthy of ascending to heaven. This is where the uplifting feel of the story comes from, as Dante depicts purgatory as a far holier place full of dedicated, motivated, loving people. While still bound by their actions, the souls here did not reject God and are not deprived of his light.

The Divine Comedy as a whole is very interested in Christian ideas of love, death, and humanity, and biblical references are too numerous to count. However, among the most notable are the examples of sin and virtue that the story presents on each terrace. The terrace of pride, for example, boasts beautifully carved sculptures of great biblical moments of humility (see Frame 4), such as Mary accepting her role as the mother of Jesus or King David dancing before the Ark of the Covenant. Counter to this, the ground is illustrated with standout instances of pride, such as Lucifer waging war on God or Nimrod constructing the Tower of Babel. Eden also appears a few times throughout the book; the serpent who tricked Eve appears at night in Ante-Purgatory, and the Garden of Eden sits at the very peak of the mountain as a transition space between Earth and paradise.

These biblical references are the essence of The Divine Comedy, as they are what grant it its namesake. Their inclusion serves to allow Dante to explore ideas of the afterlife, morality, and what it might mean to be a good Christian. By framing sins and virtues in the context of the Bible, Dante reinforces the weight of those sins and virtues. It is almost like Dante uses the Bible as a way of grounding and strengthening whatever claims he might make, especially considering that the politics of his time are a very relevant part of the story. He draws deliberate parallels between biblical sinners and those of history, and in doing so he makes a commentary on both the historical sinner and the nature of the sin itself.

Portrait of Dante by Sandro Botticelli

Illustrations of Dante and Virgil and the terrace of pride by Gustave Dore

Illustration of Mount Pugatorio by Anthony Dekker