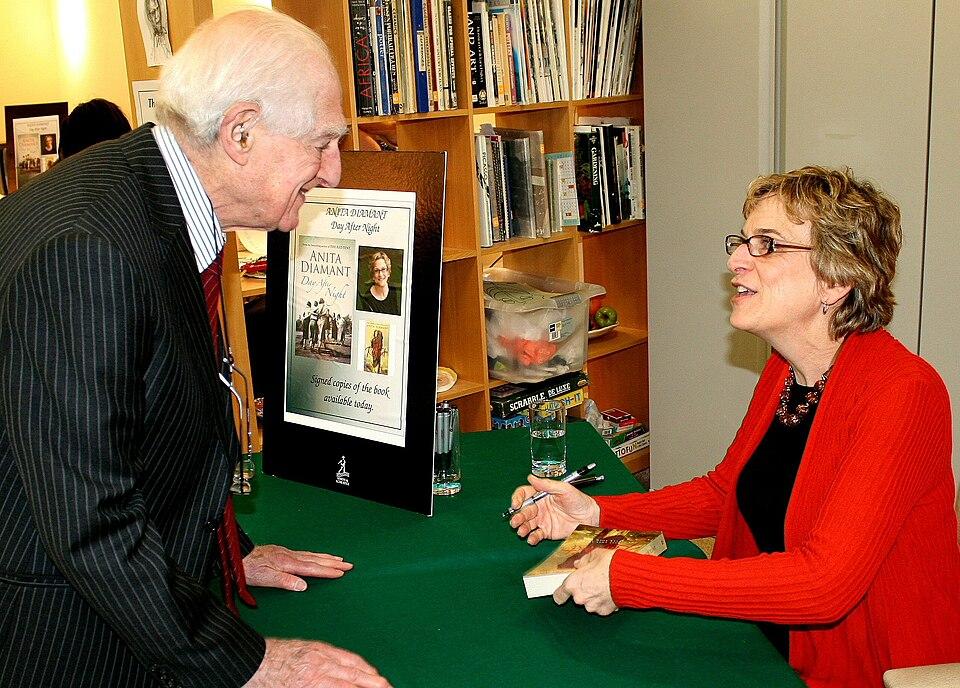

In the first plate is a photograph of Anita Diamant, the author of The Red Tent. The second plate shows an image of The Red Tent’s book cover. The third plate is a painting by James Tissot, which depicts the abduction of Dinah from the Bible’s point of view. In the final plate is an image from The Red Tent miniseries, which helps to illustrate the content of the story as Dinah is standing proud with the red tent in the background.

About the Author:

Anita Diamant is an author of fiction and nonfiction books. She has published five novels, one of which is The Red Tent, which became a bestseller. She was born on June 27, 1951, and grew up in Newark, New Jersey, before moving to Denver, Colorado, when she was 12. In 1973, Diamant received her bachelor's degree in Comparative Literature from Washington University in St. Louis. She then went on to earn a master’s in English from Binghamton University in 1975. In the same year, she began her writing career as a freelance journalist. She then went on to publish her first book in 1985 and debuted as a fiction writer in 1997 with the publication of The Red Tent.

The Author’s Relationship to the Bible:

Anita Diamant is religious and identifies as a Reform Jew. She first joined a Jewish congregation when she was 12 after her family’s move to Denver, Colorado. Now she is a member of Temple Beth El in Sudbury, Massachusetts. She also founded her own community-based ritual bath in Newton, Massachusetts, called Mayyim Hayyim: Living Waters Community Mikveh and Education Center. She has even written several non-fiction books that explore Jewish practice and life. While critiques of The Red Tent point out its historical inaccuracies, Diamant claims that the book is simply a novel based on biblical characters and is not a commentary on the text.

Plot Summary:

The Red Tent is sorted into three parts. The first part is entitled “My Mothers’ Stories,” which goes into the backstories of Dinah’s four mothers: Leah, Rachel, Zilpah, and Bilhah. This section especially focuses on the tense and complex relationships between Leah, Rachel, and Jacob, and also provides a basis for the significance of the red tent. When Jacob first sees Rachel, he falls in love with her because of her beauty. Then, nine months later, when Rachel finally gets her period, their wedding date is set. However, Zilpah sees how the lust between Jacob and Leah has been growing, and so she feeds into Rachel’s fears about her wedding night. Overcome with fear, Rachel gives up her spot as the bride to her sister, Leah. From there, a very tense and complicated dynamic is formed between the two sisters and Jacob, with Jacob engaging in sexual acts with both of them. The red tent also plays a big role in this section, as this is where all of these sexual acts occur. At the end of the section, Rachel gives birth to Joseph, Dinah’s older brother, which provides a nice entryway into the next section, which focuses on Dinah’s life.

The next part is entitled “My Story,” which focuses on Dinah’s journey into adolescence, her encounter with Shalem, as well as her family’s changing dynamics. Dinah learns how to spin, cook, and weave from her mothers, and although girls are not allowed in the red tent until they are women, Dinah is brought in with them. Dinah and her family then move to Canaan as Jacob wishes to be reunited with his twin brother, Esau. Soon after they reach their new home, Dinah gets her period. She is then celebrated by her mothers in the red tent, and they smother her with hugs and kisses. Then, as Dinah travels with Rachel, she meets Shalem, the prince of Shechem. They take a liking to each other instantly and end up making love in the palace where Shalem lives. Shalem is happy and declares that this seals their marriage. King Hamor offers a generous bride-price to Jacob, but Jacob will only consent to the marriage if all the men in Shechem agree to be circumcised. However, Simon and Levi, Dinah’s brothers, reject the union and murder all the men in Shechem, including Shalem. Dinah is covered in Shalem’s blood and is pulled back to their camp, screaming. Dinah then leaves her home forever as she walks to Shechem.

The final part of the book is called “Egypt,” which focuses on Dinah’s healing after the traumatic experiences that took place in Shechem. In this section, Dinah finds out she is pregnant and goes to live in Egypt with Re-nefer, the mother of Shalem. Her son, Re-mose, is born, and at nine years old is old enough to start school to learn the trade of a scribe. He then goes to the academy in Memphis, leaving Dinah alone. During this time, Dinah becomes closer to her midwife, Meryt, and eventually marries a man named Benia. Then Dinah is called by Re-mose to attend to the labor of his master's wife as a midwife. Later, Dinah finds out that the master is her brother, Joseph, and that he rose to power despite being sold into slavery. Re-mose also finds out that his master, Joseph, is the brother of Dinah. With this realization, he accuses Joseph of murdering his father and raises his arm to harm him before being pulled away by guards. However, shortly after, Re-mose is set free with the help of Dinah. Then, years later, Joseph appears at her door and tells her that their father, Jacob, is dying. Dinah travels with Joseph and Benia to Jacob’s camp, but Jacob doesn’t remember her. Dinah can hardly recognize her brothers as they’ve grown so much older. At the camp, a girl tells the legend of Dinah, and Dinah is pleased to hear that her story hasn’t been forgotten. Before leaving the camp after Jacob dies, Judah hands Dinah a ring that Leah wanted her to have while on her deathbed. At the end of the book, as Dinah is dying, she sees the faces of all her mothers.

Biblical Materials Relevant to The Red Tent:

The main inspiration for The Red Tent comes from chapter 34 in Genesis, where Dinah is first introduced in the Bible. Her story in the Bible is very short-lived and is defined entirely by how Shechem “defiles” her. For instance, at the start of the chapter, the story tells how “now Dinah the daughter of Leah, whom she had borne to Jacob, went out to visit the women of the region. When Shechem son of Hamor the Hivite, prince of the region, saw her, he seized her and lay with her by force” (Genesis 34:1-2). Throughout the rest of the chapter, Dinah doesn’t speak even once and is only discussed as being a sister or a daughter to the powerful men in her family. In fact, the men in her family make all the decisions for her that will greatly impact her life without even considering getting her point of view on the matter. They are outraged not at the fact that Dinah might be traumatized by being laid with by force, but by the fact that they cannot “give [their] sister to one who is uncircumcised, for that would be a disgrace to [them]” (Genesis 34:14). They also make it known at the end of Genesis 34, that they don’t want their sister to be “treated like a whore” (Genesis 34:31). Once again, this likely has nothing to do with the wellbeing of their sister, but instead with upholding their reputation and power in society.

It’s also important to point out how the third plate in my gallery relates to the Bible’s depiction of Dinah’s story. The third plate, a painting by James Tissot from 1896, shows Dinah being forcefully abducted by Shechem before he defiles her. This is exactly how the story of Dinah is depicted in the Bible, as when the prince saw her, “he seized her and lay with her by force” (Genesis 34:2). However, The Red Tent’s version of Dinah’s story isn’t merely defined by her “defiling” as it is in the Bible.

Intertextual Analysis between the Bible and The Red Tent:

The difference in how Dinah is depicted in The Red Tent, with her being able to have her own voice, thoughts, and opinions, makes for a nearly entirely different book. For instance, when Dinah’s story is introduced in the second part of the book after she finishes recounting her mothers’ stories, she is not solely described or defined as being a sister or a daughter to powerful men. Instead, her story begins with the words, “I am not certain whether my earliest memories are truly mine, because when I bring them to mind, I feel my mothers’ breath on every word” (Diamant 75). This is a stark difference from how she is introduced in the Bible. Rather than being defined by how a man defiled her, she is defined by her thoughts on a page, by exactly how she wishes to recount her own story.

Now right there is exactly what the intertextuality between the Bible and The Red Tent is all about. It’s about taking real stories and characters from the Bible and offering a different perspective that enables the experiences of the women to come through. In getting to see a different viewpoint or perspective, our knowledge of how other people might have lived during that time is expanded. We are also better equipped to explore themes such as the role of women or female empowerment, which would’ve been harder to analyze with the Bible all on its own.

To further compare the Bible with The Red Tent, it’s important to analyze how the defiling of Dinah is portrayed. While in the Bible, this pretty much sums up Dinah’s existence and is the only thing that is talked about in relation to her character, in The Red Tent, it is merely another event occurring in her life. However, it is important to point out that while in the Bible, Dinah is laid with by force, in The Red Tent, her lying with Shalem is depicted as a wonderful experience. While reading, it was shocking to see how what was originally depicted as a forceful experience in the Bible was depicted in this book. To give more context, when Dinah and Shalem first meet in The Red Tent, Dinah thinks, “His name was Shalem. He was a firstborn son, the handsomest and quickest of the king’s children, well-liked by the people of Shechem. He was golden and beautiful as a sunset” (Diamant 183). This in and of itself was shocking for me to read, because I had thought of Shalem as being evil and immoral, as in the Bible, he was described as lying with a woman by force. However, even in this one line, there is a gentleness and a warmth to the description of him. Then, as things progress between the two of them, we see what was once depicted as a forceful experience in the Bible as being a gentle and patient experience. For instance, Dinah explains that “[she], who had never been touched or kissed by any man, was unafraid. He did not hurry or push, and [she] put [her] hands on his back and pressed into his chest and melted into his hands and mouth” (Diamant 190). Also, another significant passage shows Shalem checking in with Dinah. The passage reads, “He looked into my face to discover my meaning, and seeing only yes, he took my hand...” (Diamant 190).

Similar to The Red Tent, the final plate of my gallery depicts Dinah as standing strong and as someone who is not defined by a single moment in her life. This image from The Red Tent miniseries is a perfect encapsulation of how The Red Tent portrayed Dinah in contrast to how she was portrayed in the Bible. Like in the picture, Dinah and her voice are the main focus throughout The Red Tent. Finally, through Diamant’s focus on letting Dinah’s voice be heard, we are allowed a glimpse into the lives of those that history often forgets.

Works Cited:

Coogan, Michael David, et al., editors. The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha: An Ecumenical Study Bible. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Diamant, Anita. The Red Tent - 20th Anniversary Edition (Anniversary). Picador USA, 2007.

Image Citations (in order):

“Anita Diamant.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 11 Apr. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anita_Diamant.

“Dinah.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 1 May 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dinah.

“The Red Tent (Diamant Novel).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 29 Mar. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Red_Tent_(Diamant_novel).

“The Red Tent (Miniseries).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 24 Apr. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Red_Tent_(miniseries).