Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book is a layered work that tells the story of Mowgli, a "man-cub" raised by wolves in the Seeonee jungle, guided by a set of rules he refers to as the "Law of the Jungle." Published in 1894, Kipling's tales capture the allure of the jungle while subtly reflecting the colonial dynamics of British-occupied India. The main characters -- Shere Khan, Baloo, and Bagheera--are anthropomorphized, often hinting at the cultural and racial tensions between the British and the Indian populace in the late 1800s. Kipling's life— born in India but sent to England for schooling—echoes the themes of isolation and belonging that Mowgli experiences, sparking intrigue among readers for generations.

Illustrators have continued to reimagine and interpret these stories, creating a timeless tale. The original edition features images drawn by W.H. Drake and Kipling’s father, John Lockwood Kipling, whose artistic style underscores the story’s mystique and serious nature. However, in contrast, Walt Disney's 1967 adaptation transformed the narrative, simplifying characters to fit more playful, silly, and child-friendly archetypes. Yet, Disney's choices sparked criticism, as King Louie and his monkey tribe were considered caricatures echoing racial stereotypes prevalent in American media at the time. This shift in portrayal softened Kipling’s complex jungle laws into a colorful adventure tale, losing some of the story’s cultural commentary and political subtext. Kipling’s work and reputation has since been re-evaluated; though celebrated for his literary expertise, he is also critiqued as a proponent of colonial ideologies. Even today, The Jungle Book prompts discussion on the power dynamics, racial tensions, and moral questions embedded within stories we so often think of as simply for children. As an intricate and influential work, spurring ongoing dialogue about cultural representation and moral storytelling in children's literature, The Jungle Book remains questionable due to its stance as a political allegory.

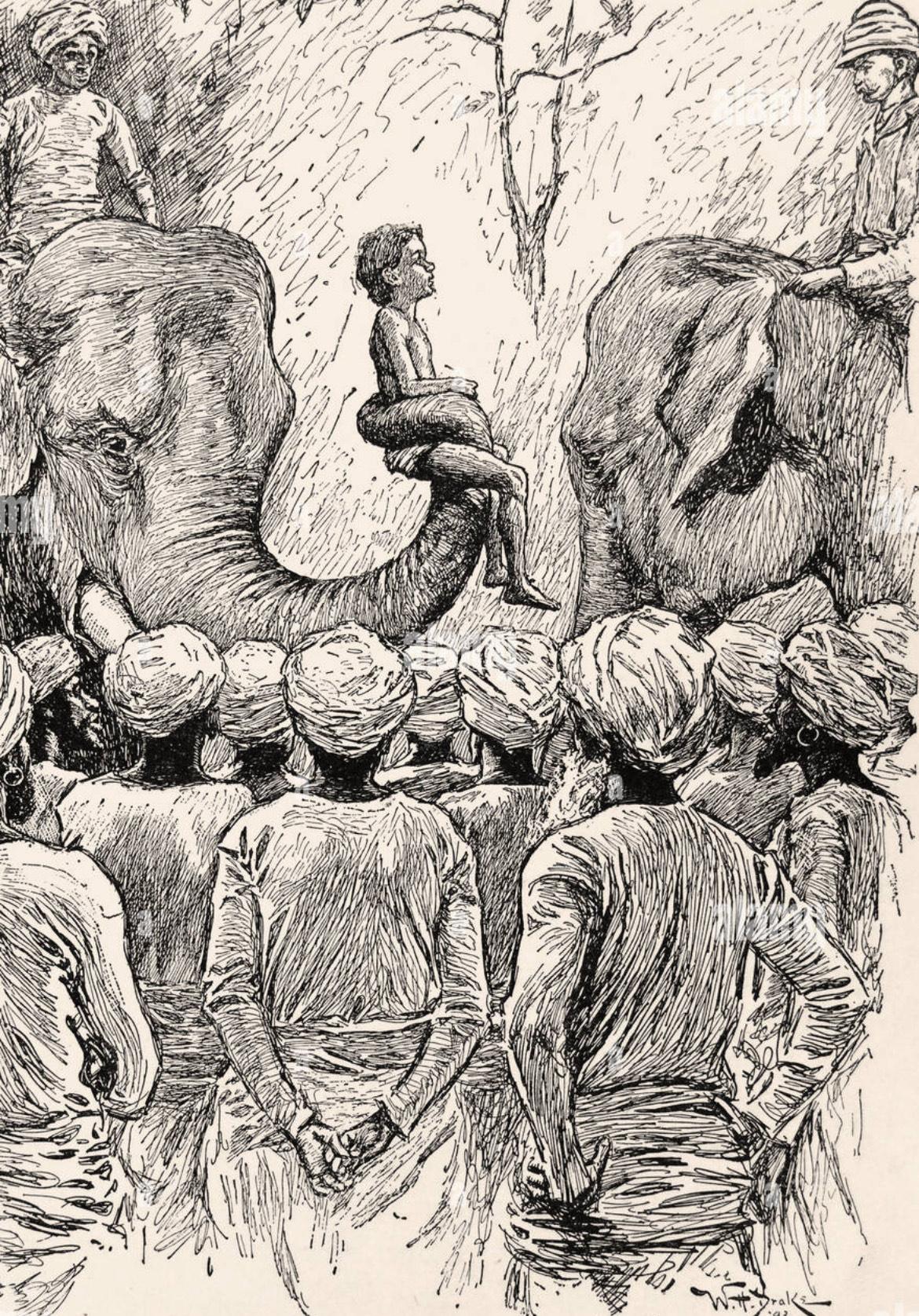

H. Drake, "Not Green Corn, Protector of the Poor, --Melons," said Little Toomai, from The Jungle Book, by Rudyard Kipling, 1894, MacMillan & Co first edition. Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book is a collection of stories published in 1894 that personify a variety of jungle animals– Shere Khan the tiger, Baloo the bear, and a boy or “man-cub” named Mowgli, who is raised by wolves in Seeonee, India. For much of the nineteenth century, the British controlled a large portion of India through the East India Company, which eventually turned into a direct ruling called the British Raj in the mid-to-late 19th century. Great tensions arose between the native people of India and the British colonizers, bringing about stereotypes of savagery and disobedience. It is thought that Kipling’s children's book reflects these intricacies, masking the impositions of British imperialism on the native people within a fictitious story. The reader also follows the theme of abandonment thought to echo Kipling’s own childhood. Kipling was born in India and raised there for his early years. He was later sent to live with a foster family in England in the 1870s prior to attending boarding school. While the novel is less about the Darwinian struggle to survive that is typically found in person-creature relationship stories, it instead highlights serious and silly human mannerisms through animals. Nodding to the didactic tradition, Kipling uses his animal leaders to teach Mowgli and, in turn, the reader to respect and obey authority and know his place in the jungle as Mowgli searches for belonging and forges his identity. The story has been published in various early editions with others illustrated by Rudyard Kipling's father: John Lockwood Kipling.

Portrait of Rudyard Kipling, 1965-1936, Poetry Foundation. Rudyard Kipling used to be a household literary name. Born in 1865 in Bombay, India, a traumatized Kipling was sent to England for boarding school; he wanted to return to India as a teen and quickly established himself within the Anglo-Indian community. He was Britain’s first Nobel laureate and one of the most widely read writers. People knew his poems by heart and read his stories to their children, teaching them morals and proper etiquette. However, in recent years Kipling’s reputation has taken a beating.

David Levine, "Rudyard Kipling," from A Gentle-Violent Man, By V.S. Pritchett, in The New York Review, March 9, 1978, issue. Having previously been accused of being a colonialist, jingoist, racist, Antisemite, misogynist, right-wing imperialist, etc. has caused his stories to be analyzed in a much different light than just a piece of children's literature. Never denying allegations of The Jungle Book being a political allegory, Kipling has held this reputation of being a political writer. Supplementing this, David Levine--a caricaturist for many publications such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, Sports Illustrated, The New York Review, Time, Newsweek, The New Yorker, The Nation, and Playboy, and others--illustrated him in The New York Review in 1978. Levine has distinguished his place as a political cartoonist, creating dramatic drawings and commentary about various figure heads and political leaders across the globe. Here, he portrays Kipling with sharp features and messy facial hair in a drawing done in pen with sharp lines, calling upon his intimidating appearance, which is eerily like his portrait. Like most caricaturists, Levine is mocking some of Kipling's features, making him look far more serious and frankly scarier than his actual portrait where his features are bold, however still softer. There is much tension within The Jungle Book that comes from the literary conflict of Kipling's idea of the “Law of the Jungle.” Throughout the story, he draws on the parallels of hierarchy and individual responsibility and those who seek to undermine it. This can especially be seen within Shere Khan, who acts as a solitary and ruthless predator against the native people. In some interpretations, "Law of the Jungle" depicts the British Raj, which was the rule of the British Crown throughout India beginning in the 1850s. Presumably “Monkey People” are the Indigenous peoples whom the British and their monopolist companies came to imperialize and civilize throughout their rule. This closer reading has led to the assumptions of Kipling's political standings on such events. This caricaturesque drawing appears again many years following in Disney’s 1967 film adaptation of the work (as in Illustrations from Disney, W. (2005)] in this case). What's interesting here is that this depiction arguably draws on racial stereotypes associated with African Americans. They speak in slang, sing scat, and dance to jazz with exaggerated features such as prominent lips, portrayals that resemble early cartoon stereotypes of African Americans.

Stuart Tresilian, “Mowgli & Kaa, Baloo and the Monkeys,” for The Complete Jungle Book (1894), by Rudyard Kipling, 2018 edition. Stuart Tresilian was a British artist and illustrator, best known for his illustrations of many children's novels and short stories. He was born in Bristol in 1891, but moved to London with his family where he went on to study at the Royal College of Art and later became an art teacher. He served in World War I where he was wounded and captured by the Germans and held at Rastatt, Baden. During his imprisonment he continued to draw; these drawings are now displayed at the Imperial War Museum. It comes as no surprise that Tresilian may have found interest in Kipling’s The Jungle Book, as it’s argued political allegory is connected to the British Raj and their colonization of India well into the 1850s, and having served for Britain we can possibly assume Tresilian’s bias towards a British rule. Tresilian’s depiction of the monkeys as muscular, large, overwhelming figures feeds into Kipling’s detail of personification and ruthlessness , giving them human-like features while portraying them as feral and savage beings. Kipling includes the monkeys for presumably the purpose of convincing Mowgli that he shouldn't stay in the jungle because of their selfish nature and unwillingness to care for one another, as seen by Mowgli's kidnapping done by the monkeys. With the knowledge of Kipling’s stance on colonialism, it’s rather interesting to connect the prejudice raised now about his work and compare to what he may have been insinuating while writing. Only when we look at these images with a more critical lens and delve into the writer and illustrator as people do we see internalized racism and inherent bias in this literature.

Illustrations from Disney, W. (2005). The Jungle Book. Disney Publishing Worldwide, courtesy of Dr. Catherine Golden’s personal library. The times of The Jungle Book challenge what Walt Disney and the company perceived to be the “right way of living” (Metcalf, 1991). While Disney rarely stated his political views, he was a Midwesterner and a middle-class conservative. In 1967, Disney released The Jungle Book. A softened version of Rudyard Kipling's original shows Disney’s shift in the portrayal of politically charged narratives. In Disney’s simplified version, characters lose much of their original complexity, which can be seen in both a negative and positive light. Kaa, for example, becomes a purely antagonistic snake, in contrast to Kipling’s depiction of him as self-serving yet helpful to Mowgli. These adaptations to the original create a more enjoyable story for the reader; however, Kipling’s purpose of presenting the reader with a set of moral lessons and life principles calls upon the book's inherent didactic undertone. King Louie represents the leader of a group of mischievous monkeys who wreak havoc on Mowgli, calling for his capture, lying to Mowgli to convince him to stay in the jungle. In traditional didactic literature, authors present misbehavior as a sin, depicting characters who are “good” as followers and those who repent for their wrong doings. Kipling masterfully blends didactic storytelling with vibrant entertainment, offering lessons on loyalty, identity, and the balance between individuality, and his depiction of social order: “the Law of the Jungle”. The value of discipline embodied in this law is woven in throughout the story. However, the work is also deeply entwined with the prejudices of Kipling’s colonial context. Animal hierarchy reflects imperialist ideals of order and control, while depictions of characters like the monkeys carry politically charged, racial and cultural stereotypes. As a result, while The Jungle Book remains a beloved narrative of growth and belonging, its colonial undertones invite critical reflection on the biases embedded within its charm. While there are still underlying motifs throughout, it is relatively easy to succumb to the colorful, playful, childish intrigue that Disney so reputably spins on traditional stories like The Jungle Book.