Walter Crane (1845–1915) is an English illustrator who scholars often herald as one of the generation's most influential and prolific creators of children's books and a central figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement and the Golden Age of Children's Literature. This exhibition covers the three main demographics for which Walter Crane illustrated in chronological order of his work: children, babies, and adults. Crane began his professional career with books geared towards children, then began to illustrate for even younger audiences, and finally created work for adult readers. While his art is broadly enjoyable and visually pleasing regardless of his target audience, there are stylistic choices specific to each audience that differentiate among them. Crane first attempted to break into the art world through academies and with more mature work like his painting The Lady of Shalott (1862), which was displayed in the Royal Academy of Arts, though the academies refused much of his work after that. It was not until he joined the publishing company Routledge, Warne & Routledge and began working on children's books that his career took off, along with those of his colleagues Randolph Caldecott and Kate Greenaway. Some of his most popular works are toy books—short books with little text and only a few highly detailed illustrations for a general child audience, as seen in The Alphabet of Old Friends (1874) and many of his popular fairy tale illustrations not featured in this exhibit such as The Frog Prince (1873), Beauty and the Beast (1875), and The Princess Belle-Étoile (1909). Surprisingly, Crane somewhat resented his success as merely a children's illustrator and thought little of his work in toy books despite the amount of care he consistently put into it. As his work gained notoriety, he was able to expand into longer works for both older and even younger audiences, such as with Baby's Own Aesop (1887) and arguably his most famous work for a decidedly mature audience, The Faerie Queene (1894-97). Although his style does differ stylistically from his more child-centric work, there is a clear throughline of his artistic tendencies that vary as is appropriate for those who will read the work, which the selected illustrations below exemplify.

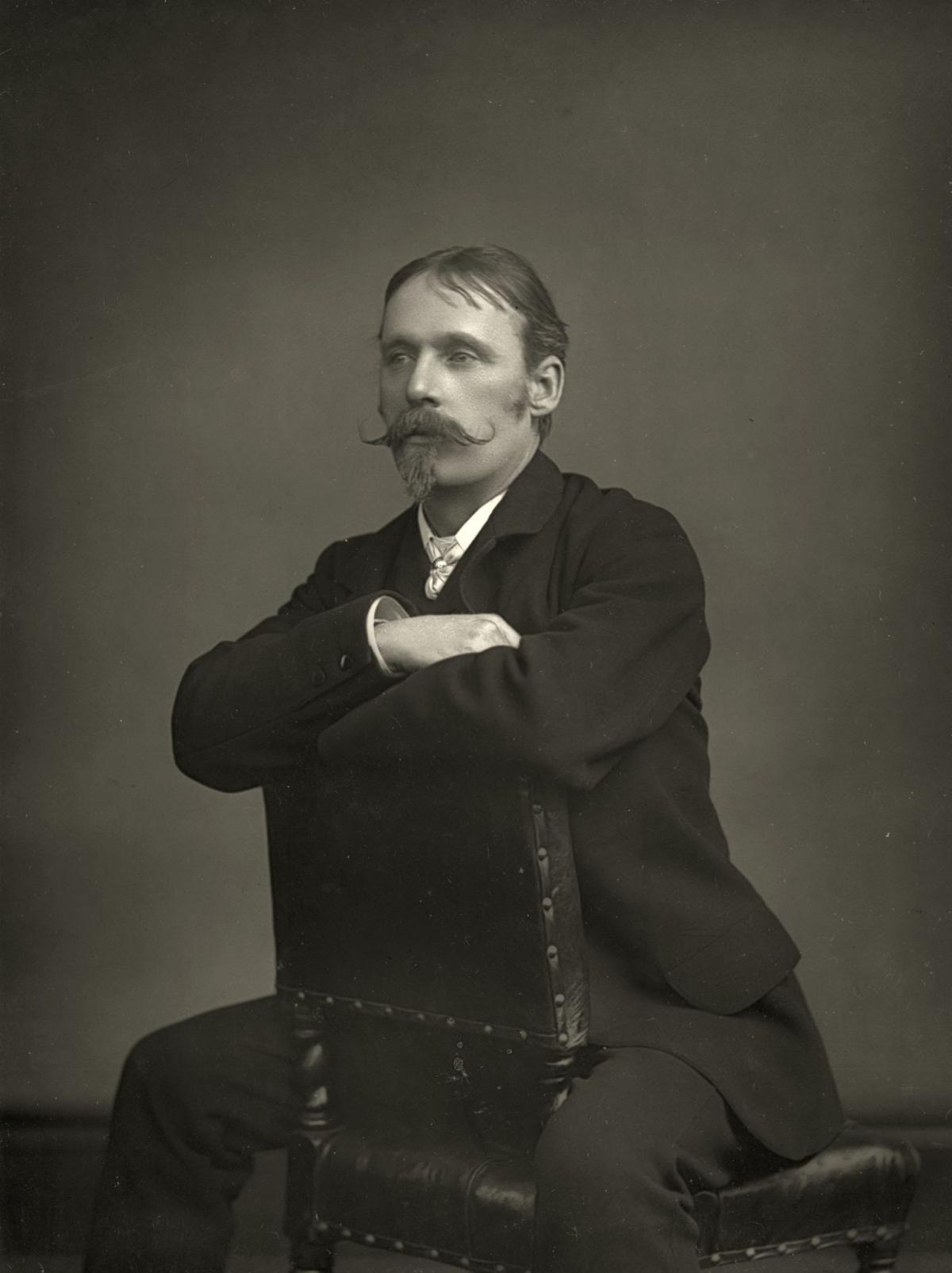

Herbert Rose Barraud, Portrait of Walter Crane, 1891, National Portrait Gallery. Noted portrait photographer Herbert Rose Barraud took this photo of Walter Crane at his London studio in 1891 when Crane was 46 years old. Crane was born in 1845 in Liverpool as the second son of portrait painter Thomas Crane. Both his older brother and younger sister went into creative pursuits, with his sister Lucy becoming a writer and his brother Thomas a children's illustrator in his own right, though Walter is undeniably the most famous of his family. His father's painting style influenced much of the beginnings of his artistic career before he eventually apprenticed under the wood engraver and printer William James Linton at the age of 13. As he learned the craft for the next three years, he also studied notable artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and Japanese print-making, all of which heavily influenced his work. In his personal life, Crane was a staunch socialist, though he often used his art to convey political messages and advance a cause. In 1871, he married embroiderer Mary Frances Andrews and together they had three children. Crane died in 1915 in West Sussex at the age of 69, just three months after his wife's tragic suicide.

Walter Crane, Plate 3 from The Alphabet of Old Friends, by Walter Crane, 1874, courtesy of The University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. This plate is from one of Crane's most well-known mediums: the toy book. Toy books were paperbound children's books that typically contained only six illustrated pages and strongly emphasized illustration rather than text. Many of Crane's popular fairy tale illustrations also took the form of toy books. Edmund Evans, premier engraver and printer of Routledge, Warne & Routledge, revolutionized the toy book market by creating a greater focus on artistic value and high-quality design; he invited Crane to work under him in 1863, first to design book covers and then for toy books and longer children's books. This particular toy book contains the standard six double-spread illustrations, each featuring the letters of the alphabet, a corresponding nursery rhyme that incorporates each letter (like Jack Sprat for J), and a drawing to go alongside it. Crane's illustration style, particularly for toy books, includes bright colors and bold outlines meant to grab children's attention, though the level of detail in the compositions puts it above standard children's book illustrations. By nature of the smaller book and the limited number of illustrations, Crane's drawings are necessarily simplified and even slightly caricatured while maintaining a level of maturity and artistry that makes the book more universally appealing. One could argue that this genre of book and subject material is more suitable for a younger audience than the didactic fables of Baby's Own Aesop (see below). But while Crane created that book specifically for babies, this one is enjoyable to a wider range of ages, including older children who might not want to read a book specifically targeted towards very young kids.

Walter Crane, Frontispiece from Baby's Own Aesop, by Walter Crane, 1887, courtesy of The Public Domain Review. This image accompanies the title page of Crane's illustrated version of Aesop's Fables, a collection of fables, each condensed to a single page (by Crane himself) to suit an especially young audience better. Like many in the book, this picture is chock full of bright colors, animals, plants, and plenty of things to keep a baby's eyes on the page. It also features an elaborate border surrounding the main image and contains matching motifs; although the rest of the book's illustrations do not include a border, this practice emerges in some of Crane's more elaborate works for older audiences. Crane indicates from the very first page who the intended reader of the book is by including a young child in the frontispiece drawing, surrounded by the animals that populate the stories within. While some of the wording of the fables contained in the book is likely too sophisticated for a baby to understand (their strong morals reflect Crane's ties to socialism), Crane makes sure to tailor his drawing style to make the book as appealing to the adults who can read the words as the babies who can admire the pretty, colorful pictures. Though Crane first gained popularity through his short toy books, his connection to the publishing company Routledge, Warne & Routledge and the success of his shorter books meant he eventually could illustrate books with as many as 54 illustrations, such as this one, which even featured his name front and center on the cover.

Walter Crane, "The Guilefull Great Enchanter," from The Faerie Queene, by Edmund Spenser, 1894, courtesy of Jonkers Rare Books. Many regard Crane's illustrations of Edmund Spenser's epic poem The Faerie Queene from 1590 as his most famous and adult work. The book is an allegorical tale told over six books about six knights and their quests for virtue in service of the titular Faerie Queene Gloriana; Crane's illustrated edition from 1894 features 88 individual plates of exquisitely detailed illustrations. This plate from the first book shows the Redcrosse Knight and his companion Fidessa (who is actually the evil witch Duessa in disguise) while at rest from their journey. It displays a significantly higher level of intricacy and maturity than his work geared toward children. Crane packs every square inch of the illustration with detail, from the field's flowers and blades of grass to the individual loops of Redcrosse's armor, in a way that would go unappreciated by his usual young audience. Each plate also features an elaborate border that matches the depicted scene, with this one containing ornate leaves and tree patterns, a royal-looking ornamentation on the top, and even a naked woman's body seamlessly woven into the flow of the branches. Crane drew from the English Gothic style and the Arts and Crafts Movement (of which he was a part) as inspiration for the illustrations that also incorporate the medieval nature of the source material to create the gorgeous, stylistically consistent compositions that make up the book.

Works Cited

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Walter Crane". Encyclopedia Britannica, 10 Mar. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Walter-Crane.

Kosik, Corryn. "Walter Crane – Illustration History." Norman Rockwell Museum, 1 Mar. 2018, https://www.illustrationhistory.org/artists/walter-crane.

"Walter Crane." Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, 17 Dec. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Crane.

"Walter Crane Biography." WalterCrane.Com, 21 Oct. 2015, https://www.waltercrane.com/biography/.