Introduction

“The White Man’s Burden” written by Rudyard Kipling, is an example of latter colonial, pro-imperialist poetry, that supports imperialism on an ethnic or racial basis, rather then a nationalistic one. It also is based on the premise that the true cost of empire is burdened by the conquerors in the case of European imperialism, and that the conquered benefit from the transaction. By 1899, when Rudyard Kipling published the poem, many could have argued that the British Empire was coming to a close, although the serious downfall of the empire would take another 50 years. However, the American era of conquest was only beginning, especially in areas other than the continental United States. This poem was preceded by the U.S. invasion of the Philippines, and this poem was written in response to this event, as an encouragement to the U.S. to take a larger role in world wide empire, with Kipling viewing the United States as the Anglo Saxon children of Britain, and therefore a rightful heir to the gap that the declining British empire would provide on the world stage.

This poem saw a mixed response across the U.S. with some publications mocking the fundamental concept of empire or imperialism being a positive influence of the subjects, while other publications published artwork showing the United States and Great Britain has allies, bringing peace to the Earth through shared territorial acquisition and non-violent competition. One of the most common artistic responses to the poem, sometimes published as a companion to the piece, was to personify the various nations of Europe and their overseas

Work Cited

Hamer, M. (2009, October 18). “The White Man’s Burden” (1899) Notes. The white man’s burden. Retrieved September 16, 2021, from http://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/rg_burden1.htm

Images

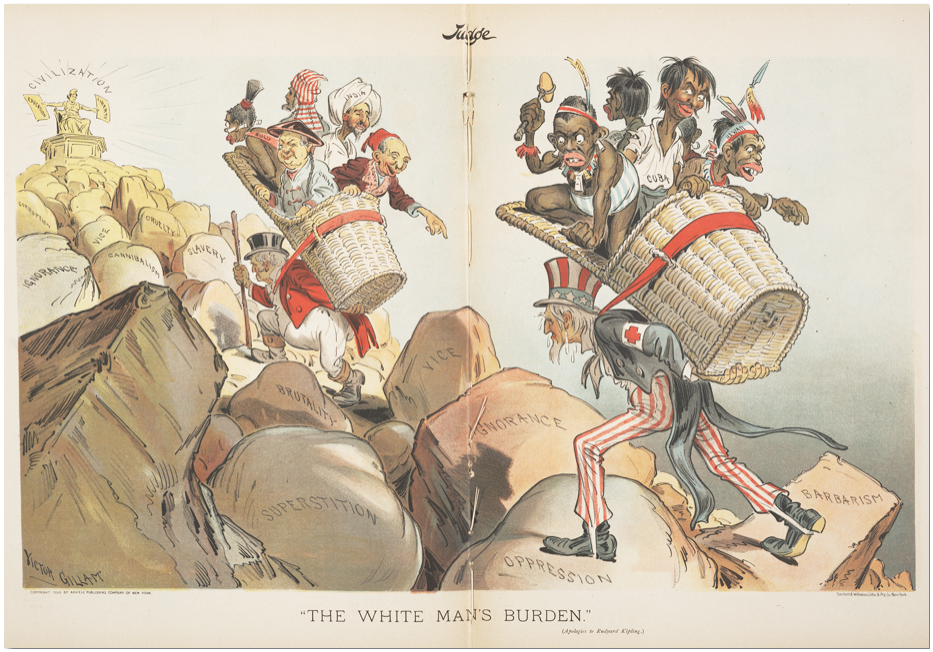

Fig 1: “The White Man’s Burden” Victor Gillam, Judge Magazine, 1899

This cartoon, published in 1899 as a companion to the poem, shows John Bull (a personification of Great Britain) and Uncle Sam (a personification of the United States) carrying their colonial acquisitions to civilization. Judge Magazine was a weekly satirical magazine at the time of the poem, aimed at young men and published in the U.S. Judge Magazine was started by a group of Puck cartoonists who left their employer and originally struggled due to their competing market, but Judge came to overcome Puck in circulation. Uncle Sam is shown to be carrying Cuba, Puerto Rico, Filipino (Philippines) and Hawaii by name, with a Samoa headband on the personification of Hawaii, while John Bull carries Zulu, China, India, Soodan (Sudan), and Egypt. Some of the colonies of the U.K. (India and Egypt) are shown as looking judgmentally back at the more barbaric U.S. colonies while others are looking forward to the light of civilization, but all U.S. colonies except Puerto Rico look back to Barbarism and Oppression, shown here as the boulders the U.S. and U.K. must climb over to deliver their colonies to civilization. The boulders of Slavery, Cruelty, Canibalism and Curruption are shown as yet to be overcome, while civilization holds the flags of Education and Liberty. The U.S. colonies are also drawn as much more animalistic, half-devil as Rudyard Kipling would put it.

Fig 2: The White Man’s Burden” Detroit Journal, 1898, author unknown

The Detroit Journal was a daily newspaper provided at a low cost twice a day to Detroit residents. This cartoon plays with the same analogy as the one published in Judge above, but removes the U.K. personification from the image, and limits the carried civilisations from specific colonies to an African man. Civilization here is shown as the schoolhouse, and the man carrying the African is labeled U.S. on his gun powder canister. The U.S. flag is shown in the background, next to a trading station and ship. The labeled boulders are not present in this representation, but it is still seen as an up-hill battle. The African man is dressed in ferns and wearing primitive jewelry, and is barefoot, while the personification of the U.S. wears stereotypical frontier clothing and boots. This plays upon a theme of the African being unwilling or undesirous of education, but it also being beneficial to them as a race.

Fig 3: The White (?) Man’s Burden” William Henry Walker, Life Magazine, 1899

This cartoon, published in Life Magazine, parodies both the poem and the other two cartoons, inverting the relationship to show the colonies of the U.S. and the U.K. as carrying them. My understanding of the order is U.S., France, Germany, and the U.K. from left to right. This is part of a long history of Life holding an anti-imperialist standpoint. Life was a humor and general interest magazine at the time, competing directly with Puck and Judge. Life was for a more elite magazine than the competition, owned by two Harvard graduates at the time. The U.S. is carried by the Philippines, the U.K. by India, and Germany, represented here by Kaiser Wilhelm, is carried by Africa. The boulders are still present, but go unlabeled here, and notably there is no destination pictured. Their colonies are shown as stooped over, much like how the Judge magazine cartoon showed John Bull and Uncle Sam.

Fig 4: -And Peace Shall Rule”, Udo Keppler, Puck magazine, 1899

This demonstrates the Anglosphere alliance of the U.S. and the U.K. as bringing peace to the world, colonies first, which is why Asia is highest on the globe. Puck began as a German language magazine, but was published in America, as a humor magazine, the magazine began to be published in English as well due to financial reasons. It was seen as a non-partisan satirical magazine celebrating good government and the success of American constitutional values (Thomas 2018). Peace is shown here within an explicitly Christian context, with Asia being lifted up to heaven, with an angel in flight. The name Puck is a reference to the character of the same name from A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Shakspere, due to his mischievous and whimsical character. Typical targets of Puck’s satire included corruption on both sides of the aisle, as well as women's suffrage, the Catholic church, and unions. The main audience was American men of the middle to upper class, and the English version grew to have a circulation of 80,000. John Bull and Uncle Sam here represent the U.K. and U.S. respectively.