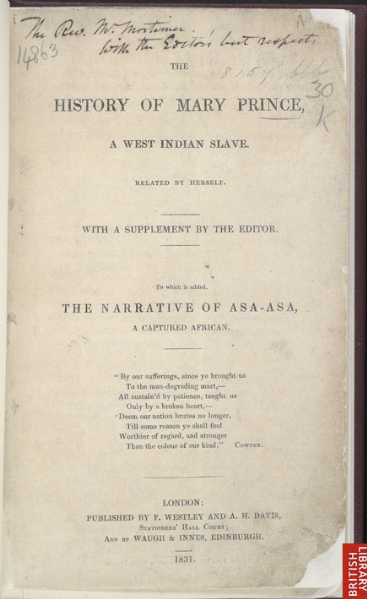

The History of Mary Prince is the narrative of an enslaved woman, Mary Prince, who shares the horrors of slavery and exposes the true capacity of enslavers' cruelty through her experiences on her journey to freedom from Bermuda to England. Her narrative was edited and published in 1831 by Thomas Pringle through F. Westley and A. H. Davis publications in London. Though considered to be autobiographical, the extent of Pringle's role in the transcription and publication of Prince's history are highly controversial; his contributions later revised in a 1997 adaptation by Moira Ferguson.

In the original publication, though Pringle writes of Prince's role, "The narrative was taken down from Mary's own lips...written out fully...pruned into its present shape; retaining, as far as was practicable, Mary's exact expressions and peculiar phraseology," (Pringle qtd. Prince) her narrative is repeatedly compressed by footnotes and "sandwiched between white and black male-authored texts, as if a black woman's story is inadequate on its own and needs the authority of a white man...to make it complete" (Baumgartner 9). Pringle's 'supplement' was nearly as long as her narrative, shorter by just eight pages. Despite working to expose the injustices faced by Prince and defending her against critics, Pringle's approach and supplemental assertions provide that Mary is simply a tool to be used for the 'greater good,' abolition; he writes, "But after all Mary's character, important though its exculpation be to her, it is not really the point of chief practical interest in this case (Pringle qtd. Prince 10). Likewise, the implications behind Pringle's inclusion of a defamatory letter from Mary's previous enslaver, Mr. Wood, one that Pringle admits 'would probably never appeared' if not for his use of it, must be interrogated. His attention to Mr. Wood, who slandered Prince heavily and was the source of much difficulty in the narrative's publishing, seems to be of as much importance to him in this publication as Prince herself, "Prince's goals appear lost, or at least eclipsed, in this struggle between Pringle and Wood" (Baumgartner 11).

In addition to the personal liberties taken by Pringle in the relaying of Prince's history, the need for excessive supports to validate her credibility in telling her story and the claims in Wood's included letter of her untrustworthy promiscuity contribute to a climate of distrust and misuse of Black women, one where "it is not surprising that the former slave's body became the battleground for the ensuing controversy" (Baumgartner 11). This feeds directly into mainstream narratives surrounding the character of Black women; where "the pro-slavery lobby is content to portray Prince as an immoral, untrustworthy sexual monster," despite no evidence of validity in the claims as well as character witness testimonies refuting it, such as that included in the novel written by an old colleague of Mr. Wood, Mr. Phillips (Baumgartner 12). Mr. Wood, like many in the pro-slavery lobby, stand to gain from discrediting Prince and others like her--they work to ensure that Black women's testimonies of the abuse suffered at their hands will be invalidated and dismissed.

In analyzation of the contemporary implications presented by the narrative's conception, publication, and reception, the liberties normalized to be taken in the right to Black women's stories and lives; the insinuated necessity of validation or approval from a White man to validate Black women's credibility; the devaluing use of Black women as a 'tool' to serve personal agendas; the normalization of placing Black women's bodies and credibility up for display and debate; and the dehumanizing perception of Black women as expendable and acceptable sacrifices to be made are important to consider. Through the lens of this historical context, the ways these ideas have evolved in the systemic racism that informs medical malpractice on African American mothers today can be identified.

Excerpts: A Closer Look at Prince

Passages of Prince's narrative present that this disbelief in Black women as a credible source, even in the telling of their own life story, extends to disbelief of their ability to feel emotional or physical pain. Prince relays, "We...worked through the heat of the day; the sun flaming upon our heads like fire, and raising salt blisters...Our feet and legs, from standing in the salt water...soon became full of dreadful boils...in some cases to the very bone" (Prince 10). Her diction leaves no room for oversight of the severity of their pain, with graphic descriptions such as 'flaming upon our head like fire...dreadful boils...in some cases to the very bone.' Calling attention to the inhumane treatment she was forced to endure, she forces the audience to recognize they are not machines for production; they are human, they feel, they suffer, and they are in danger. Notably, "the external surroundings are given more agency than her body," reflecting the loss of autonomy she was also forced to endure (Baumgartner 5). This describes the climate from which evolved the widespread medical malpractice performed on African American mothers today; they are disbelieved in their personal testimonies, disbelieved in their capacity for pain, and refused the autonomy provided much more readily to their White counterparts.

In one of the many cases where Prince provides that her brutal experience is far from singular, she describes an instance exemplifying the complete disregard in the suffering and lives of Black mothers and their babies through Hetty's story, an enslaved pregnant woman punished for a cow's escape. Prince recalls, "My master flew into a terrible passion...flogged her as hard as he could lick...till she was all over streaming with blood. He rested, and then beat her again and again...poor Hetty was brought to bed before her time, and was delivered after severe labour of a dead child...her former strength never returned to her...she died" (Prince 7). Her description of Hetty's dire condition, 'streaming with blood,' followed by her enslaver's subsequent rest and continuation emphasize the extreme damage inflicted and the relentless power exerted in these deadly blows. Hetty's story portrays not only the lack of value placed in the lives of Black mothers and babies, but the active violence readily and exhaustively enacted against them; a scene that sets the stage for the evolution of injustice presented in the medical malpractice in the treatment of African American mothers today.

Works Cited

Baumgartner, Barbara. "The Body as Evidence: Resistance, Collaboration, and Appropriation in 'The History of Mary Prince.'" Callaloo, vol. 24, no. 1, 2001, pp. 253-75. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3300499. Accessed 23 Apr. 2024.

Prince, Mary. The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave. 1831. Proquest, http://ulib.iupui.edu/cgi-bin/proxy.pl?url=http://search.proquest.com/b….