Much of the joy of teaching a course I designed on “The Victorian Illustrated Book” comes from introducing students to the rare book room at Skidmore College. Even senior English majors are often surprised to discover that Special Collections exists at a small liberal arts college. In the rare book room, we study physical books, serials, and prints in the forms they appeared to the Victorians when they were first issued, though some have been rebound or put in archival boxes for safe handling. Illustrations—a vital part of the reading experience even of sophisticated Victorians—were studied, as author-illustrator George Du Maurier has put it in “The Illustrating of Books from the Serious Artist’s Point of View,” "with passionate interest before reading the story, and after, and between” (Magazine of Art [1890] I: 350). Applying Du Maurier’s viewpoint, I teach students in this class to “read” like a Victorian. Students learn to glean information from meaning-laden symbols, gestures, and wall and mantel decorations in illustrations created by caricaturists, Royal Academy-trained artists, and, in some cases, the authors themselves. We also trace the arc of the genre by following the development of illustrative storytelling from the serials of the 1830s to graphic novels of our own time; along the way, we explore the change in aesthetics from caricature to realism and the intricate relationships between authors and artists.

As the semester progresses, we engage in archival work to create an exhibition on a topic of the students’ choice centered on the Norman M. Fox Collection (Fig. 1), a significant holding of Victorian illustrated books, multivolume works, and serials. When the pandemic hit in March of 2020, the class was poised to begin brainstorming the exhibit’s “big picture,” to borrow a term from Beverly Serrell’s Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach (1996). When my college turned to online learning, I had a week to come up with a plan to adapt the second half of my course. The coronavirus pandemic led me to COVE (The Central Online Victorian Educator).

Figure 1. Books in the Fox Collection, Skidmore College

Figure 1. Books in the Fox Collection, Skidmore College

I had billed the mounting of an exhibition as a highlight of “The Victorian Illustrated Book.” In this unit, students choose topics for display cases located in the library and the English Department hallway. They are asked to contribute to the exhibit theme on an aspect of Victorian literature and culture, select 3-5 illustrations for the display case, write captions, formulate an introduction to the case, and arrange books and artifacts in an engaging, attractive way to teach viewers about the subject. I was reluctant to drop the exhibition component from the class. This course is one of very few on campus that engages students in archival studies. And designing a library exhibition as an undergraduate at Brown University sparked my own decision to become an English professor. When I read Dino Franco Felluga’s post on the Victoria listserv about using COVE to transition to online teaching, I wrote to him immediately about the possibility of creating a virtual gallery in place of a brick-and-mortar exhibit. Within a week—even before they knew what the acronym stood for—my students and I had accounts on COVE.

The platform is very easy to navigate. Moreover, there are ample tutorials on how to create maps, timelines, and exhibitions and how to annotate nineteenth-century works housed on The Central Online Victorian Educator. The support I received from the editors was prompt, helpful, and reassuring. Editor Dino Franco Felluga offered past syllabi to showcase ways to use COVE and encouraged me to try the Chronology feature as well as the Gallery builder while technical editor Dave Rettenmaier helped me navigate issues I encountered uploading images and selecting an icon for the exhibit. I spent time looking through and learning from a range of previous COVE exhibitions and encouraged my students to do the same. While I did not want to launch the exhibition gallery without my students’ input, concomitantly I realized I needed to understand how to use the platform to be able to instruct my students. I created a Group entitled “The Victorian Illustrated Book, Spring 2020” (Fig. 2) and posted some material to orient my students to the exhibition component of our course now on COVE. The next step was to get my students to join this group; for some, this took a few tries because students attempted to create their own groups rather than join the group I started.

Figure 2. "The Victorian Illustrated Book, Spring 2020," COVE Dashboard

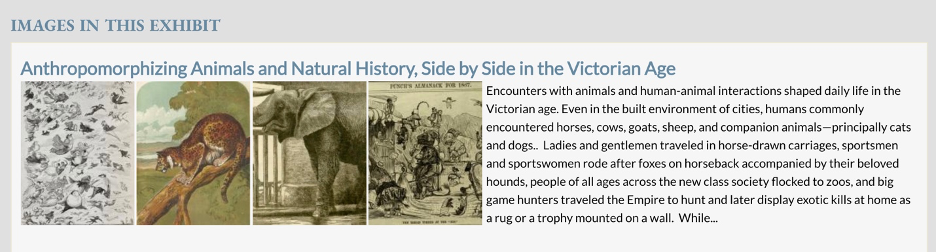

Our class met synchronously on Zoom twice a week during our regularly scheduled class times. After a Zoom session brainstorming potential topics for our class exhibit, we chose the topic of animals in Victorian literature and culture and titled our gallery “A Victorian Menagerie.” Sharing the screen on Zoom, we looked at several previous exhibitions. We were literally drawn to one COVE gallery entitled “Drawn to Books: Women Illustrators of the Birmingham School” by Dr. Rebecca Mitchell and her students in “The Pre-Raphaelite Circle,” a course she taught at the University of Birmingham. “Drawn to Books” includes multiple images in a single entry to give the illusion of a display case. We decided that each student in the class would create a virtual display case (hereafter referred to as a case) of 3-5 images on a theme that related to our chosen topic on animals in the Victorian age. I created an introduction to the gallery and the opening case, modeling to students how images might work together in a case, the purpose of captions and correct formatting as well as how an introduction orients reader-viewers to the ways images work in relation to each other in a given case to convey a particular exhibit thread. My case entitled “Anthropomorphizing Animals and Natural History, Side by Side in the Victorian Age” (Fig. 3) includes public domain images from Skidmore’s Fox Collection, which is partially digitized, and The Victorian Web, also a huge resource for my students.

Figure 3. "Anthropormorphizing Animals and Natural History, Side by Side in the Victorian Age," opening case in "A Victorian Menagerie"

In creating my own case, I encountered a few small issues that I overcame with COVE support. Images can be uploaded in a range of formats (png, gif, jpg, and jpeg), but they need to be less than 20 MB but larger than 640x480 pixels. Although a few of the images I wanted to upload did not fall within these parameters, I resized them in Photoshop and uploaded them successfully. A bit harder to resolve was how to create a case composed of 3-5 images that were not drawn from the same source. As we saw in “Drawn to Books,” COVE allows a user to upload multiple images for one entry, which is an asset. However, the platform permits the user to identify only a single artist and date for multiple images in any given entry. “Drawn to Books” includes multiple images from the same source in an entry, but we wanted to gather images from a range of sources for one virtual case.

To work around this problem, I left the “Artist” tab blank and listed “19th century” in the “Image Date” tab since all the images I and, in turn, my students used date to the long nineteenth century. The “Description” box does not limit the user to a certain number of words or characters. I took advantage of the unlimited space to create a proper citation for each of the four images in my case—noting the artist, title of the image, name of book or journal, the precise date, the source of the image, and, in some cases, the name of the person who scanned the image. Captions for each image followed the citations (Fig.4). The text I wrote also modeled how the introduction to the case explains how the four images I chose relate to one another to present my theme. In this way, I adapted the COVE platform to allow for the creation of multiple images within a case to mimic the design of brick-and-mortar exhibitions. The students, in turn, successfully modeled this format for their own cases.

Figure 4. Multiple Captions in one Description Box

In creating actual exhibitions in past years, students worked in groups of two or three, designing a case collaboratively. Our rare book room does not have enough display cases for students to work independently. With the move to online learning, each student could now create his or her own case, which proved advantageous since class members were now located in Rhode Island, Indiana, New York, New Jersey, and Singapore. During class Zoom meetings, students consulted with each other to make sure there was no repetition among their chosen topics. The students’ topics reflected their personal interests. The “Preview of Images” (Fig. 5) shows how the cases collectively illustrate the manifold ways the Victorians treated animals, anthropomorphized animals, put animals on display, making animals an indelible part of Victorian culture.

Figure 5. Gallery of Cases for "A Victorian Menagerie"

Some students focused on a particular animal—birds (Fig. 6), horses, dogs, and the British lion—and raised relevant themes, such as the establishment of the Audubon Society to protect birds and their ecosystems, the creation of the RSPCA to stop the abuse of animals, Anna Sewell’s literary protest of animal abuse in Black Beauty where a horse speaks for equine rights, and the symbolism of the lion to convey the power and authority of Britain.

Figure 6. "Birds in the Victorian Age," for "A Victorian Menagerie"

Other students concentrated on the work of one artist and examined, for instance, the connections between humans and animals in the work of animal artist Harrison Weir (Fig. 7), who was fascinated by Darwin’s theory of evolution, and the naturalism in the illustrations of Beatrix Potter, noting the influence of her artistic mentor, Sir John Everett Millais.

Figure 7. "Harrison Weir: Parallels Between Humankind and Animals," for "A Victorian Menagerie"

Still others chose a thematic approach to examine, for example, the roles of animals across the social classes in showcasing horses and hounds and the domesticated pet for the upper reaches versus livestock associated with labor and the working class; pet keeping of rabbits, frogs, and dogs from notable figures including Beatrix Potter, Emily Brontë, and Queen Victoria to demonstrate what Harriet Ritvo in The Animal Estate (1987) calls the Victorian “cult of pets” (Fig. 8); and the dressing of animals in human clothing to illustrate what George Cruikshank in George Cruikshank’s Table-Book (1845) refers to as “social zoology.”

Figure 8. "Keeper from Life" by Emily Bronte, from The Victorian Literary Cult of Pets," for "A Victorian Menagerie"

No doubt prompted by class discussions on Zoom, connections emerged across the cases, giving cohesion to the exhibit. For example, Beatrix Potter’s illustrations appear in three of the ten cases; images of dogs and cats in, respectively, three cases and two cases; Tenniel’s Alice illustrations and Punch cartoons in, respectively, three cases and two cases; horses in two cases; Cruikshank’s images in four cases; and George Du Maurier’s zoo cartoons in two cases. In speaking to each other and forming a gallery, the cases visualize an era that witnessed the rise of animal protection, pet keeping, zoos, and natural history as it beheld animal abuse, a fashion industry that posed a threat to animal populations, and widespread fascination by and fears of our animal ancestry, sparked by Darwinian evolution. Alongside wild animals and domesticated pets, we also find in “A Victorian Menagerie” animals dressed in Victorian clothes to point to social vices, human foibles, and inequalities in wealth and education across the social classes.

Sharing our cases as they progressed and watching them come together proved rewarding to the students who ranged from first years to seniors. All sensed they were part of a shared collaboration and appreciated contributing actively to their curriculum. Some students took to COVE more readily than others; three students finished their cases well before the due date and two finalized their cases minutes before the deadline. Particularly fruitful were the class Zoom workshops devoted to our gallery on COVE. I divided students into breakout rooms and moved among them to discuss their particular cases and ways to make them stronger. Students also helped each other to navigate the platform. One student, for example, figured out how to move images within a single case to make a more effective arrangement, and she, in turn, explained to the rest of the class how to manipulate the images in a case. Some students were so impressed by the introductory caption written by one student that they modeled their introductions on hers. And all the students enjoyed the ability to continuously revise and edit their captions and upload and delete images to achieve a combination of images that conveyed their chosen aspect of animals in the Victorian age. Since the platform also allows for the group manager to access the student entries, I was able to silently make final edits on content and grammar for clarity and accuracy.

An accompanying chronology places “A Victorian Menagerie” in an historical context. The chronology feature of COVE uses the technology of Timeline JS, which I had previously used to create a timeline on the evolution of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Creating a chronology on Timeline JS is labor intensive, but I was pleased by the result and used the timeline in “The Victorian Illustrated Book” to teach the evolution of Alice from an oral tale to films and merchandise in popular culture today. Truly remarkable is the ease in creating a chronology through COVE, which allows users to draw on the many resources already uploaded onto COVE and to add our own entries to particularize it. I did not require students to create entries for the timeline and had hoped for a more vigorous response. The few students who added to the timeline found the process straightforward and quite similar to the creation of our gallery and enjoyed the process and product.

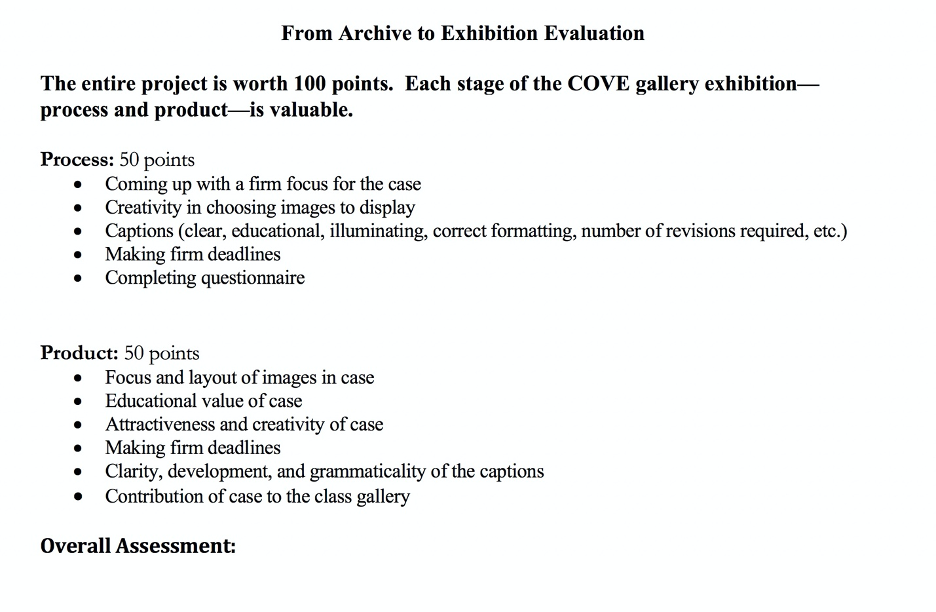

Evaluation of our work on COVE took two forms. I assessed each student’s case, giving attention to their process and their final product. I shared with the students a rubric (Fig. 9) of specific criteria gleaned from specialists in our rare book room and Serrell’s Exhibit Labels.

Figure 9. Rubric for Assessing Cases in "A Victorian Menagerie"

But I also asked students to fill out a questionnaire to evaluate their experiences on COVE.

The open-ended survey includes the following three questions: how has your experience on COVE informed your understanding of Victorian literature and culture and book illustration? What are some strengths of creating an online exhibition gallery through this open-access educational platform and what do you like about it? What are some of the limitations of COVE and changes you would like to see to make it more user-friendly? The students all signed an agreement to give permission for their responses (identified by their initials) to be incorporated into an article to be published on COVE.

All but one student found that COVE benefited their understanding of the Victorian period. The students enjoyed looking through the site and spent time outside of class viewing the annotated editions, past galleries and exhibits, and the Master Map. Praise from one student speaks to the ways that COVE opened up her understanding of the Victorian age:

Having access to COVE helped me to realize that there was an extremely wide digital network of Victorian works. COVE gave me access to many things I could only get through Skidmore’s rare book room or from a professor while I was at school. I had no idea how vast the culture of illustration was in the Victorian era, but with it all in one place it was easy to realize the truth. The network is extremely packed with rich information. (MH)

To quote another student: “COVE has shown me the depth and breadth of Victoriana that I had not known about before I accessed the site” (TL).

The responses to the question on COVE’s strengths were positive. Students noted the ease of using COVE; “The platform was straightforward and user-friendly,” one student responds. Others note how they could work on their cases at all hours: “we constantly have access to it and are able to change/adapt it more freely than if we were to create an in-person exhibit” (TR). Many liked how they could edit their captions and rearrange their images to find the best arrangement; as one student writes, “There is the ability to add, delete, and change images, descriptions, and captions until one is satisfied with the final project; it lets you ensure in real time what the end result will look like” (TL).

Another strength that emerged from the survey is appreciation of being able to collaborate across distances and work as a team, even during this unprecedented pandemic. Addressing this point directly, one student shares: “COVE has been a great tool for our class given the circumstances of our quarantine lives. . . . Our full online exhibit was able to look cohesive without actually having to meet in person” (MH). Another student highlights the team-building that COVE facilitates; to this student, COVE helped our class to overcome the obstacle of physical separation: “I have been able to view the work of my classmates throughout this process, which made creating our exhibition feel much more like a team effort, even if we were physically distant” (SY). And many students note how COVE is a widely accessible medium. They could share their exhibit with a broad audience and preserve their digital exhibit for use beyond the college classroom. To quote one student: “The exhibition is a great resource to have in an online writing portfolio for a potential job and internship opportunities” (SS).

The main limitations students perceived with COVE cluster around three areas: uploading images by multiple artists per case, restrictions in design features, and the nature of a virtual as opposed to a physical exhibition. Perhaps echoing my main frustration with the platform, some students wrote in their surveys that they wished they could identify the illustrations by different artists in one case rather than “having one huge text box for all our writing. I would have enjoyed caption boxes for each illustration I uploaded for my case” (SS). The single most widespread complaint was the wish for more variety in font size, color, and typeface “to play around with” (SY). To quote one student, “we were not able to add personal touches to our cases that we would have been able to do by decorating a physical case. . . Simple things like being able to change the background of our online case or to add borders related to Victorian life might have helped to make a lively exhibition” (MR). Another student who had mounted an exhibit in a previous class notes: “In creating a physical exhibit, we would normally have the option to vary font, font color, background color, and other small details that can add to the versatility of a case” (RO). Because of the “fewer opportunities for formal design” (RO), another student laments, “everybody’s exhibit looks really similar” (TR).

Student criticisms about caption boxes and design features might easily be addressed by expanding the software options for creating a gallery. The third concern centers on the nature of technology itself, however. Some students expressed that they were “disappointed that our peers at Skidmore will not see the exhibit on campus” (MH). Reaching a wide audience beyond Skidmore is arguably the trade-off here. Others wished for a means to evaluate our exhibit. In past library exhibitions, students placed a large poster board on an easel with post-it notes for students to write down what they learned from the exhibit. Since the platform does not include a mechanism for gallery evaluation, we sent the link to interested individuals and received feedback that was valuable to the class.

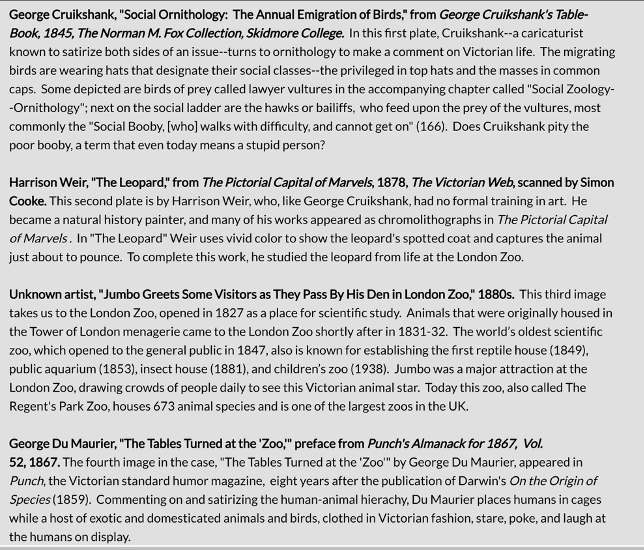

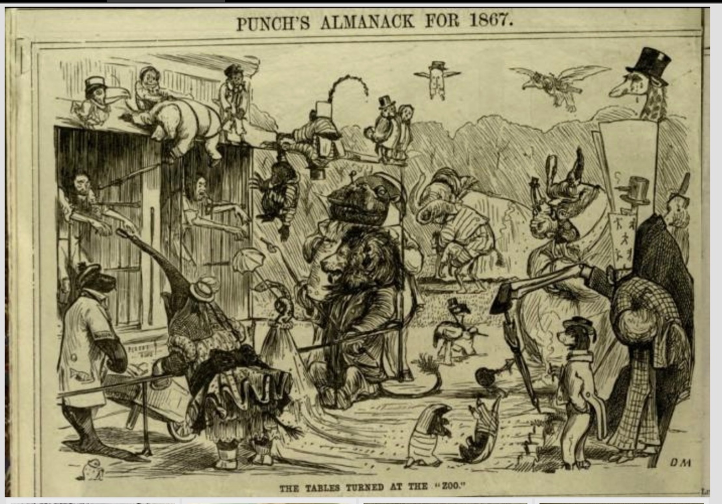

Nothing can replace the pleasure of arranging rare books, prints, and material objects in a display case, choosing fonts for the captions, mounting the captions on colored cardstock, and decorating with lace and ribbons—this process is what hooked me into devoting my life to studying Victorian illustrated books. But a former student of mine who had taken this course (and is currently teaching English at Boston University) aptly points out a distinctive advantage to the online format: “COVE clearly allows your students to do much of the work they would have done with a traditional, physical exhibit. The images come out so clearly on the website - I actually appreciate the ability to see each image up close, even more clearly than if it were in a glass case!” (EN). COVE allows reader-viewers to get up close and personal with Victorian illustrations, packed with meaningful details as in “The Tables Turned at the ‘Zoo’ (Fig. 10). Captions are also easier to read online than when placed into a display case.

Figure 10. George Du Maurier's "The Tables Turned at the 'Zoo,'" Preface from Punch's Almanack for 1867

For Spring Term 2020, the semester when the coronavirus turned the tables on higher education, COVE helped me to transform a crisis into an opportunity. Separated by physical distance and time zones, my students formed a close-knit virtual community and taught each other about the Victorian age. Together we found a refuge for Victorian art, literature, and culture in the COVE.

- Catherine J. Golden, Professor of English and the Tisch Chair in Arts and Letters, Skidmore College

Works Cited

Cruikshank, George. George Cruikshank’s Table-Book. Edited by Gilbert Abbott A’Beckett. Punch, 1845.

Du Maurier, George. “The Illustrating of Books from the Serious Artist’s Point of View.” The Magazine of Art, 1890, no. 1, pp. 349-53; no. 2, pp. 371-75.

Ritvo, Harriet. The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in Victorian England. Harvard UP, 1987.

Serrell, Beverly. Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach. AltaMira Press, 1996.

Appendix

Primary sources for “The Victorian Illustrated Book,” EN 222W at Skidmore College:

Carroll, Lewis. Alice's Adventures Under Ground. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1965.

‑‑‑‑‑‑‑. The Annotated Alice (which includes Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass). Norton, 2000.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Oxford World’s Classics, OUP, 2008.

Golden, Catherine. Serials to Graphic Novels. UPF, 2018.

Potter, Beatrix. The Tale of Benjamin Bunny. Penguin, 2002.

‑‑‑‑‑‑‑. The Tale of Peter Rabbit. Penguin, 2002.

Ruskin, The King of the Golden River. Dover, 1974.

Secondary Sources for “The Victorian Illustrated Book”:

Hacker, Diana. A Pocket Style Manual. New York: St. Martin’s, 2004.

Serrell, Beverly. Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach. Rowman and Littlefield, 2015.

The full syllabus for EN 222W, “The Victorian Illustrated Book,” can be accessed on the COVE Teaching Resources page.