A study of British writers who were inspired by the visual arts, artists who adopted literary subjects, and writer/artists whose creative acts formed a composite of the two arts. This timeline tracks the progress of our class.

Timeline

Table of Events

| Date | Event | Created by |

|---|---|---|

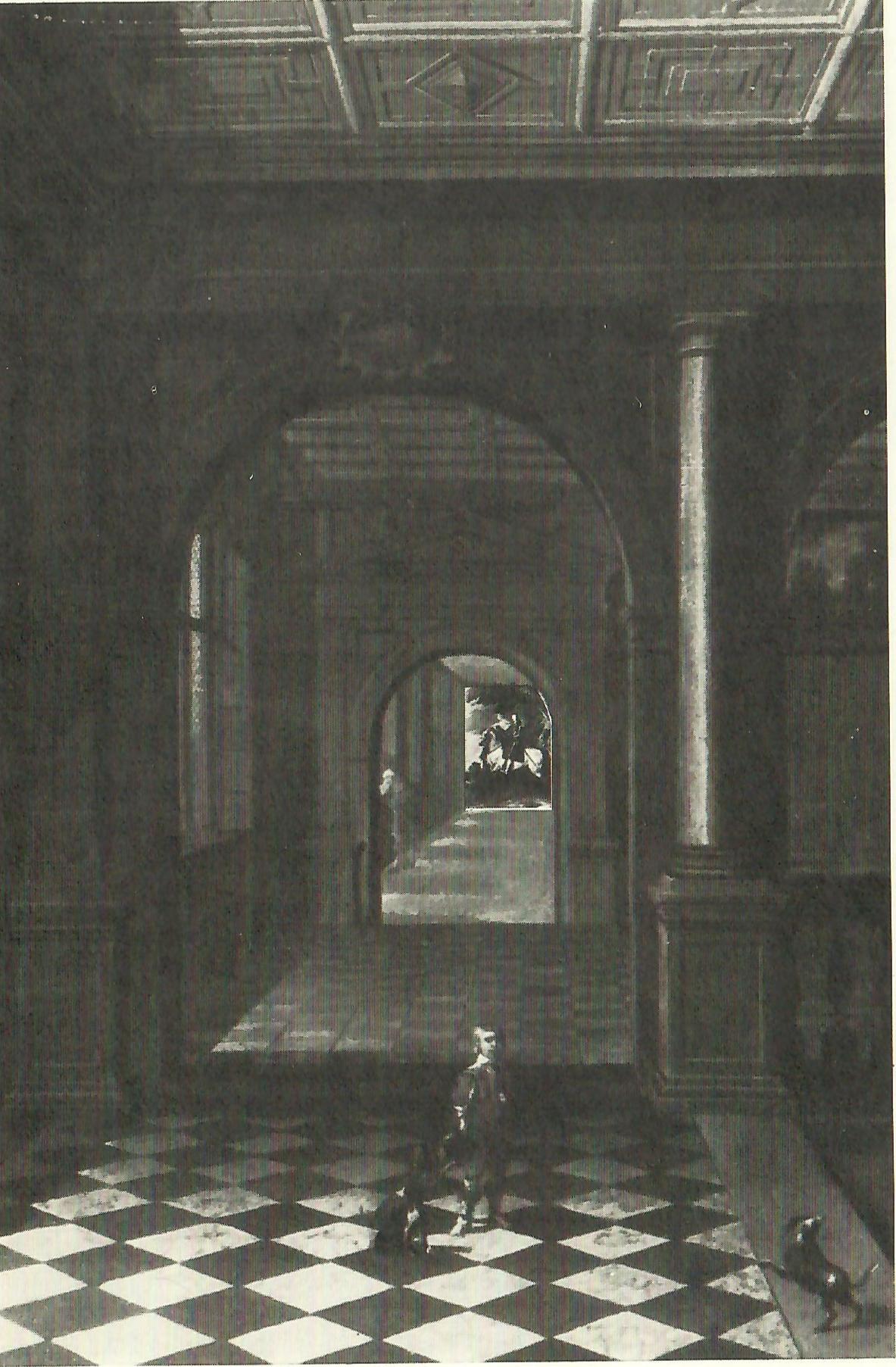

| 1633 | Van Dyck, Charles I of England, a Grand Style portraitAnthony Van Dyck, Charles I (1600-1649) with M. de St Antoine (oil on canvas, 12.1 ft x 8.8 ft, 1633; Royal Collection, Windsor Castle); Wikimedia. Van Dyck (1599-1641) was a Flemish artist, whom the Stuart monarch, Charles I, appointed painter to the English court in 1632. Along with another celebrated Flemish artist of the period, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Van Dyck typified the Continental artist on whom Charles relied rather than cultivating native English artists. Among the greatest art collectors of his age, Charles instinctively turned to France, Netherlands and Flanders, Spain, and Italy to define the taste of the court. Van Dyck was especially known for the Grand Style portrait, in this example also an equestrian portrait. The huge canvas depicts Charles in military armor, astride a noble steed and riding through a triumphal arch. The architecture alludes to the triumphal arches of the ancient Roman Empire, which were erected for powerful generals and emperors returning from a great military victory. The symbolism enforces Charles's absolute power; and since he is accompanied only by his riding master, M. de St Antoine, instead of surrounded by cheering crowds, the symbolism also enforces his "Personal Rule" — referring to his decade of ruling without Parliament, an absolutist monarch justified by Divine Right. The picture was originally hung at the end of the Long Gallery in Hampton Court Palace, creating an illusion of the king entering the palace in a blaze of power (Roy Strong, Charles I on Horseback, Viking, 1972, 14, 20-25). |

David Hanson |

Alexander PopeIn 1711, poet Alexander Pope (1688-1744) published his first major work and entered London literary circles, including Joseph Addison's. Starting in 1715, he achieved fame and income with his translations of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. He inherited his association with the Sister Arts from his uncle, Samuel Cooper, a painter who earned a reputation as “Van-Dyke in little.” Pope himself ventured into sketching and painting by studying in the studio of the portraitist Charles Jervas around the years 1711-1713, living in Jervas’ London studio and using the Jervas’ address up until 1726.

This friendship is memorialized in Pope's poem, "Epistle to Mr. Jervas, dated early 1719. A 1715 portrait of Pope by Jervas depicts Pope’s preoccupied and distant state of mind when starting his translation of Homer. In a (date) letter to his lifelong friend, Martha Blount (1690-1763), who is believed to be the woman in the background of his portrait, he wrote: “Fame is a thing I am much less covetous of, than your Friendship; for that I hope will last all my life, the other I cannot answer for.” Later, Pope established other kinds of relationships with portrait painters, appropriate to his growing fame and the political and cultural controversies to which he responded as a satirical poet. While Pope sat for many portraits, he commissioned Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723), who had taught Jervas, for history paintings in 1719.

Kneller may not have had epistles written about him as Jervas had, but Pope still expressed his admiration for Kneller through his writing. Pope paid his compliments to Kneller for these paintings he had made by writing in 1719: “To Sir Godfrey Kneller, On his painting for me the Statues of Apollo, Venus, and Hercules' (1719):

What God, what Genius did the Pencil move When KNELLER painted These? Twas Friendship—warm as Phoebus, kind as Love,

And strong as Hercules.”

Portraiture has a strong hold through the 1730s, even after Kneller’s passing. At this time, Pope had moved on from translations and turned towards being a satirist. Portraits of Pope in this decade come from Jonathan Richardson Sr. (1667-1745), a painter who had literary aspirations. Richardson’s paintings were one of the distinguished collections Pope would have seen, larger than Jervas’s. Pope’s own collection was seen as not in the taste of a virtuoso—it lacked distinguished paintings done by old masters (da Vinci, Rembrandt, or even Rubens) and history paintings. His only histories were the ones he had commissioned Kneller to create for his staircase in 1719.

Pope’s years as a satirist produced works such as Moral Essays (four poems published in 1731-35), An Essay on Man (1733-34), and his masterpiece, the four books of The Dunciad (last being published in 1742). The content Pope wrote on was philosophical, ethical, and critical.

Upon his passing in 1744, it is claimed that friends surrounded him in his villa in Twickenham. |

Amelia Moran | |

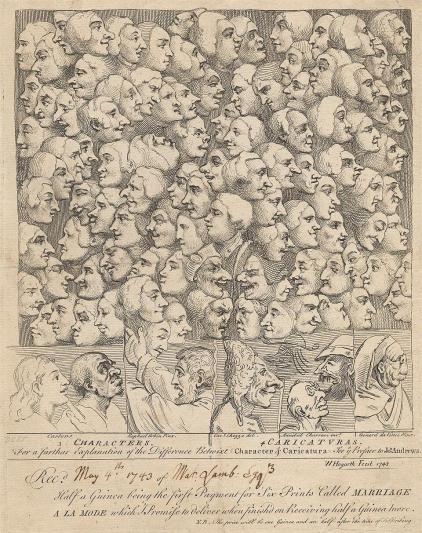

William Hogarth (1697-1764)William Hogarth (1697-1764) was an English satirist, cartoonist, and painter who was famous for his “Modern Moral Subjects,” which were series of paintings that formed a connected narrative and served as a satirical critique of English society. Hogarth reproduced the paintings as engravings for sale, and some series originated only as engravings. In the early eighteenth century, a new satirical art form became popular in England: portrait caricatures. Previously, the form had been practiced in the seventeenth century by elite circles in the Roman art world. They were first popularized by Pier Leone Ghezzi (1674-1755) and typically this type of portraiture exaggerated prominent features of a person. Ghezzi’s caricatures were done humorously rather than maliciously, and permission was granted by the sitter for the work to be done. However, caricatures were based on phrenology, the pseudo-science that asserted the physiognomic fallacy that character can be read in features, since personality traits were located in the brain and consequently the shape of the skull. Caricatures exaggerated such physical features as representations of moral attributes such as greed or voraciousness. Later on, George Townshend (1742-1807) would use caricatures to satirize English military figures. Hogarth strongly opposed Ghezzi’s work, likely because he believed it undermined the status of his own art. Rather than seeing his art as an exaggeration of history and English society, Hogarth saw his satires as works of observation. Subscription tickets for viewing his Marriage a la Mode series addresses the difference between Ghezzi’s caricatures and his paintings of “comic” history. His work, Characters and Caricatures, depicts the difference between “character” and “caricatures,” which is that “character” depends upon observation, whereas “caricatures” are created through serendipitous scribbling (essentially haphazard sketching guided by prominent features of the sitter). In the lower center of the crowd, Hogarth is believed to have inserted portraits of himself and Fielding grinning at one another. The image above of Characters and Caricatures depicts Hogarth’s view regarding the differences between the two terms. The “character” drawings present physical features (on people) that are less dramatized than the caricature counterparts. Hogarth viewed his work as an observation and reflection on English society whereas he viewed caricatures as a form of exaggeration. |

Jacob White | |

| 1711 | Joseph Addison, "The Spectator," and Coffee House CultureThomas Rowlandson (1757-1827), The Coffee House (pencil, pen, and watercolor on paper, 1790; Aberdeen Art Gallery); Art UK. In 1711, Joseph Addison (1672-1719) and Richard Steele (1671-1729) founded the daily periodical, The Spectator, to bring "Philosophy out of Closets and Libraries, Schools and Colleges, to dwell in Clubs and Assemblies, at Tea-Tables and in Coffee Houses" (Spectator, no. 10). The two writers came together from opposing political perspectives to craft a prose of disinterested, civil observation by its fictional characters "Mr. Spectator" and fellow members of the Spectator Club. Literary historians have treated the periodical's daily installments as a progenitor of the serialized, epistolary novel (Benedict 6-7). The social context of The Spectator and other periodicals was the coffee house, which served coffee, chocolate drink, wine, brandy, and punch, and which became hubs for conversation, news, and deal-making among middle-glass gentlemen. The houses tended to host specific professions -- artists at Old Slaughter's, literati at Will's, dancers and opera singers at the Orange, and so on. During the Restoration, Charles II attempted to close them, suspecting "treasonable" conversations since people of all ranks were admitted, but his opposition was stymied by his own cronies who habituated the scene. After the Glorious Revolution, Addison idealized the coffee houses as upholding civility and learning more constantly than was likely. Nonetheless, when James Boswell -- the biographer of the essayist Samuel Johnson -- came to London from his native Scotland, he loved to frequent the coffee houses and imagine himself as "Mr. Spectator" himself (Brewer 35-40). Benedict, Barbara M. "Joseph Addison." The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature, edited by David Scott Kastan, Oxford UP, 2006, vol. 1, 6-10. Brewer, John. The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century, Farrar Straus Giroux, 1997. |

David Hanson |

| 1720s-1780s | Conversation PaintingThe “Conversation” Portrait entered mainstream English circles in the 1720s, originated as an offshoot of French rococo art, wherein artists began communicating through their work the complexities of human relationship, specifically those found within a social setting. It was brought on by a softening of artistic conventions in the French court following the death of Louis XIV (1638-1715). Early English artists in this form, such as William Hogarth (1697-1764) and Philip Mercier (1689-1760), used the Conversation piece as a vehicle for examining and satirizing the seedier side of British society. Hogarth’s A Modern Midnight Conversation, which he split between a Before and an After, portrayed a salacious woodland rendezvous between a young man and a young woman. In the first illustration, the young man is seen pleading with the young woman, who is herself portrayed as behaving modestly, casually denying his advances. In the second illustration the roles are reversed, as now it is the woman who clings to the man, and the man who appears disinterested. The content of the Conversation portrait evolved a great deal in subsequent years. Young and ambitious artists began using the form as a way to introduce themselves to the broader artisan scene. The genre began hyper-focusing on sociability—illustrating the means through which social gatherings might facilitate personal association. By the latter half of the 1730s, the Conversation portrait began to fall out of favor. Artists started reshaping the form, moving away from its earlier iterations to depict moments of quiet intimacy between their subjects. A chief example of this is Joseph Highmore’s (1692-1780) Mr Oldham and his Guests, which was believed to have been an affable response to Hogarth’s Modern Midnight Conversations. The portrait is a subdued one, its red-faced subjects only slightly tipsy and behaving in a mellow manner as they wait for their companion, the titular Mr. Oldham, to return home. Unlike the earlier Conversation pieces, where the subjects were often presented far from the viewer, and framed in a remote way, the subjects here are framed closer, as if to make the setting and scene feel more intimate and personal. Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), in his piece The Painter’s Daughters Chasing a Butterfly, similarly favored intimacy over scale, framing the tandem subjects in much the same way as Highmore. By the 1760s, with the ascension of Charles III, a new variation of the Conversation portrait began taking shape. Actor-manager David Garrick (1716-1779) commissioned the German-born artist Johann Zoffany (1733-1810) to illustrate a piece for Garrick’s forthcoming play, The Farmer’s Return. This piece, and others like it, acted as a way to promote theatrical productions and puff up the social stature of the performer who had them commission. Beyond that, through its construction, it blurred the boundary between theatrical performance and painted genre scene, creating a new form of the Conversation piece altogether. |

Wilkins Dowdy |

| 1758 | Gavin HamiltonGavin Hamilton (1723-1798) was a Scottish painter, dealer, and archaeologist who took a systemic study of classical antiques during the 1750s and 1760s. In 1748, he arrived in Rome to study portrait painting. While in Rome two architects James Scott and Nicolas Revette encouraged him to visit Herculaneum and view the recently discovered site of Pompeii. These freshly discovered ruins in Athens, Naples, Palmyra, and Dalmatian coast were disseminated throughout Europe in treatises with detailed descriptions, picturesque landscape views, reproduction of frescoes, and attributes the great, beautiful, strange imagination in the middle of sense. In 1751 Scotland, he painted a full length portrait of Elizabeth Gunning Duchess of Hamilton in a conventional style from Van Dyck. Whilst then choosing to return to Rome and stay there for life in 1752. During his stay, he encouraged and got to know all British artists in Rome during the second half of the 18th century. In 1755, Hamilton met Raphael Mengs and Johann Winckelmann who were the leading theorists on Neoclassicism. Neoclassicism was the effort to revive the glories of lost civilizations. Winckelmann's book on Neoclassicism in the 1740's was about moving the model of classicism from Rome to Greek. The neoclassical movement was intensified for Hamilton after his discoveries of Greek Civilization artifacts during his time as a dealer and belief that 'the ancients have surpassed the moderns, both in painting and sculpture.' With Winckelmann's influence, his push for a newer thought of classical nobility made trouble for political parties as it sent a message to the oligarchs and challenged their rulings. |

Lacy Coleman |

| 1752-1818 | Humphry Repton, and The Red BookHumphry Repton (1752-1818) was among the foremost—and last—great designers of the classical tradition in English landscape gardening. Repton was educated at a grammar school in Bury St Edmunds and Norwich, and, anticipating a career in mercantilism, was sent abroad to the Netherlands to continue his schooling. It was the connections he made while abroad that taught him the finer points of mixing with high society. Repton famously tried his hand at various careers before turning to landscape gardening—including trade, farming, and even journalism, all of which were said to have contributed a great deal to his later successes. Working during a transitional moment in taste, he balanced the naturalistic style of the earlier Georgian landscape with emerging picturesque and more formal revival elements. Despite early success and a wide clientele among Britain’s landed elite, financial difficulties and declining health marked his later years. Nonetheless he remains one of the most influential figures in the history of English landscape design.

Unlike some of his well-regarded predecessors, Repton didn’t involve himself with executing the plans he mapped out, but rather worked exclusively as a designer. He would carefully document his proposals in illustrated presentation books known as Red Books—so-called for having been expertly bound in distinctive red morocco leather—which combined practical plans with watercolor overlays to show before-and-after views of estates. While Repton claims to have made roughly four hundred Red Books, only about one hundred still extant.

Two of these Red Books are housed at The Morgan Library, in New York City. They are the Red Book of Ferney Hall and of Hatchlands in Surrey. Repton's process consisted mostly of him visiting a specific client, touring the grounds of the estate, interacting with the client and discussing expectations the client might have, and then compiling all his cumulated notes and drawings together into a single proposal. The proposals were often pretty elaborate, and would include expectations Repton had, different views of the property and the surrounding country, and a conclusion, in which Repton would praise the client's excellent taste and, at the same time, urge them to spend a large amount of capital in improving the appearance of their estate.

Regarding the Ferney Hall estate, Repton was commissioned by Samuel Phipps, a prosperous attorney, who in 1787 sought to improve the state of his newly acquired home. This was an early endeavor of Repton’s, and as such he was still perfecting the format of the Red Book. Repton focused primarily on establishing his practical expertise, picturesque sensibilities, and cultivated taste, traits which would no doubt impress an individual as elite as Phipps.

Repton died at the age of 65, and his body currently resides in the graveyard of the Church of St Michael, Aylsham, Norfolk.

Below is an example of an overlay picture as seen in the Red Book of Ferney Hall. The left image is with the overlay up, and the right is with the overlay down. The following link will connect you with a video on the Morgan Library site where they discuss, in detail, the history of the Red Book. https://www.themorgan.org/videos/humphrey-reptons-red-books

|

Wilkins Dowdy |