The text of Quatrain 88 of Edward FitzGerald’s second-edition translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, and Edmund Dulac’s accompanying illustration work together to enforce the Orientalist undertones of the 1909 Hodder and Stoughton edition of the Rubáiyát. Quatrain 88 [Figure 1] reads:

Oh, Thou, who Man of baser Earth didst make,

And ev'n with Paradise devise the Snake:

For all the Sin the Face of wretched Man

Is black with—Man's Forgiveness give—and take!

This quatrain follows the typical AABA rhyme scheme of FitzGerald’s translations of the Persian rubá’i. It is also typical of a Rubáiyát stanza in FitzGerald’s capitalization of significant words such as, “Thou,” “Man,” “Earth,” “Paradise,” “Sin,” and “Forgiveness.” Capitalization of words that were not proper nouns or the first word of a sentence was considered an antiquated convention by the mid-nineteenth century. Therefore, FitzGerald’s heavy-handed capitalization strategy does more than draw the reader’s attention to words that contain key themes of the quatrain—it compels the reader to feel as if they are uncovering the ancient wisdom of Omar the Sage.

Quatrain 88 echoes the themes of religious skepticism and heretical doubt that run throughout the Rubáiyát. The poet-speaker asks “Thou,” presumably God, why he would create “Man,” just to mold them from “baser Earth.” Why would God create Paradise and then “devise the Snake,” damning "wretched Man” to blacken their faces with “Sin”? The poet-speaker seems to question if sin is the fault of the individual sinner or simply the result of the way in which they were made. They voice their anger and frustration towards God, stating that “Man’s Forgiveness give—and take,” indicating that man has the power to forgive (or refuse to forgive) God for bearing them into a world of sin. The poet-speakers seems to view sin as the fault of God, a radical, near blasphemous stance.

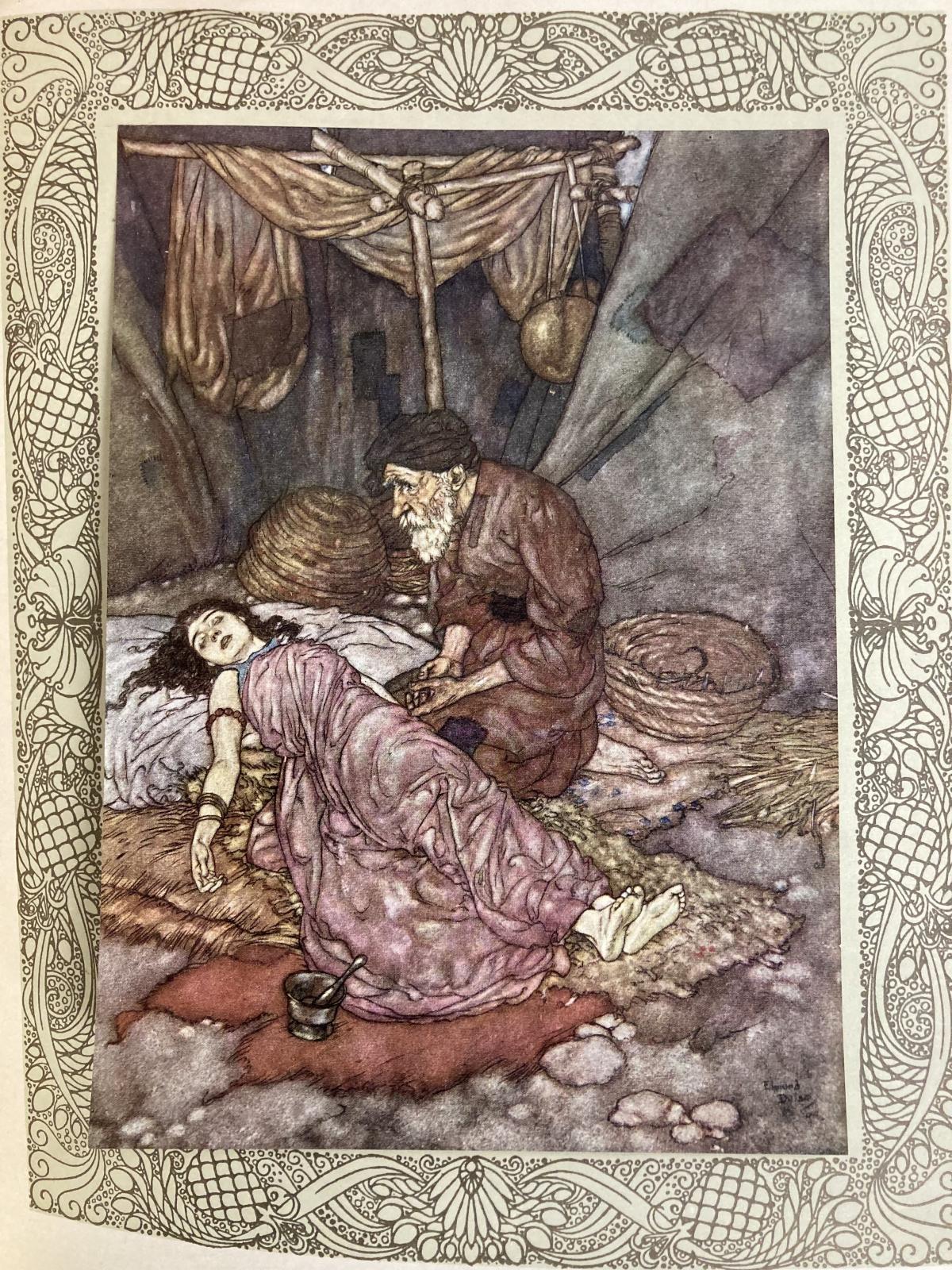

Dulac’s interpretation of Quatrain 88 [Figure 2] is soft and somber, instead of fiery and angry. His chosen color palette is muted and dark, composed of earthy brown, gray, and purple shades. The subjects of the illustration live in obvious poverty; they are surrounded by patchwork tents, woven baskets, and rags, a stark contrast to the luxurious palaces depicted in many of Dulac’s other illustrations. A wan young woman clad in a purple robe lies on the straw; she is sick, dying, or dead. A mortar and pestle lies to the girl’s side, indicating that whatever efforts made to heal her have failed. An old man, presumably her father, hunches over her, his hands clasped in his lap. Rather than look down at his daughter, he gazes off into space. His empty and defeated countenance implies a crisis of faith. In this sentimental illustration, Dulac seems to ignore the quatrain’s controversial discussion of sin, focusing instead on grief, a subject absent from the original quatrain. Religious doubt, the central theme of quatrain, seems to take a backseat to the tragic scene of the death of a beautiful exotic woman. This disconnect mirrors the physical disconnection of the illustration from the text of the quatrain, as the plate appears on its own leaf several pages after the text of the quatrain and is covered by a superfluous guard sheet.

The fin-de-siècle enthusiasm for the Rubáiyát may partially be explained by the centrality of Christianity to nineteenth-century life, and cultural norms that emphasized qualities such as purity, piety, and temperance. Naturally, the Rubáiyát’s hedonistic messaging resonated with a repressed populace whose minds were being opened by scientific discoveries, rapid industrialization, and social reform movements. However, the fact that the Rubáiyát was considered acceptable material for the widely transmitted form of the bourgeois, family-friendly gift book is somewhat surprising. Pairing some of the Rubáiyát’s more contentious stanzas, such as Quatrain 88, alongside the work of a popular illustrator like Dulac may have distracted the reader from the contentious nature of the text itself, shifting the reader’s focus to the beauty of Dulac’s illustrations and wrapping them up in a gilded gift book package. Perhaps associating religious doubt with the foreign and Oriental made this message more palatable to a mass-market audience.

Works Cited

FitzGerald, Edward, translator. Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Illustrated by Edmund Dulac, Hodder and Stoughton, 1909.