In Barbara Black’s work, On Exhibit: Victorians and Their Museums, she argues that the beautification of the Rubáiyát is directly related to its status as a piece of culturally appropriated literature. She argues that, through his translations, FitzGerald softened the appearance of the poem, commodified it, and made it seem less daunting, less other, through the use of his editing and changes. Through his translations and the commodification of the book, Black argues that Victorian and, in this context, 1930s-era publishers and readers have removed it from its original cultural context and turned it into something “recyclable, reproducible exoticism” (Black 64). Through the stylistic choices of FitzGerald’s translation, he has made this appeal something that readers of the time could view as “other” without it having a different enough face for them to feel as though it cannot be owned by them. It simultaneously treats the piece as something from a far off, mystical land through its artwork stylistic choices, and makes it accessible and inauthentic enough to be a commodity to consumers of the time. Thus, FitzGerald’s translations and the culture of gift books turn a piece of Persian culture into a souvenir for western audiences.

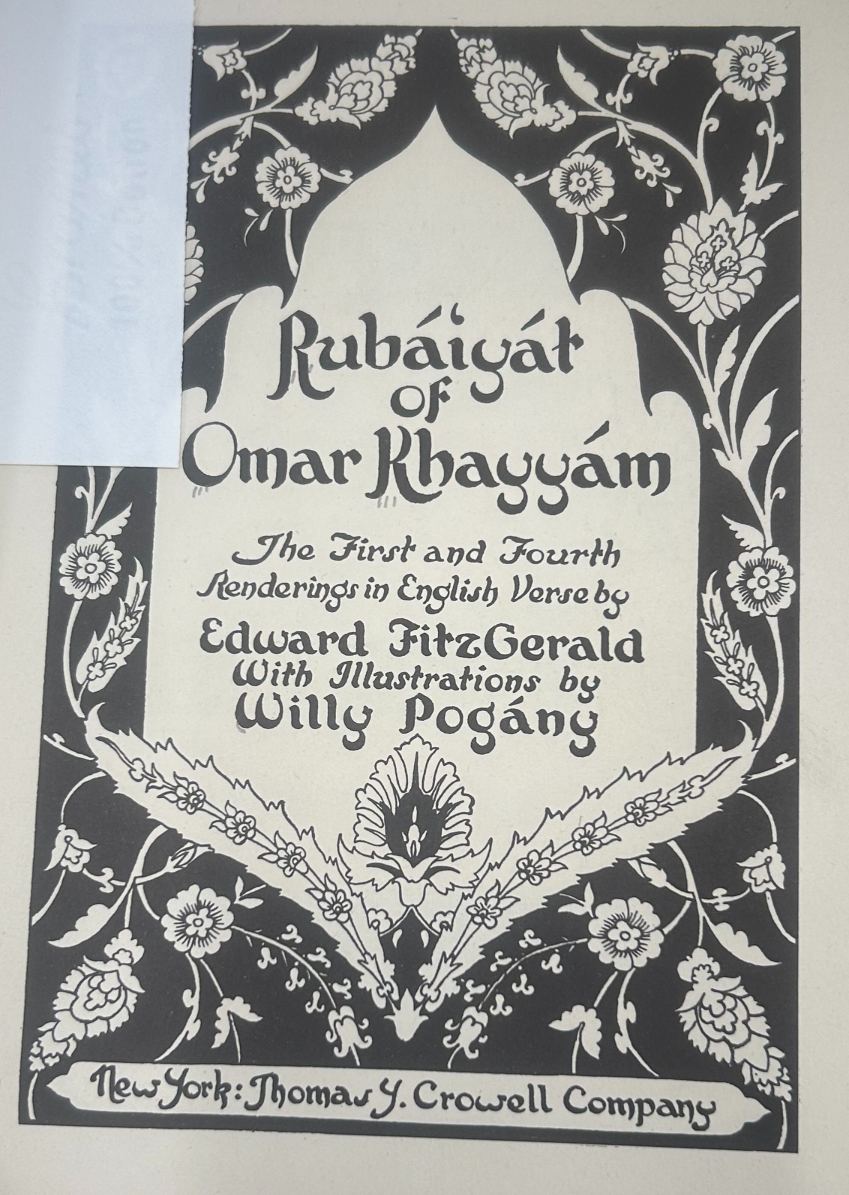

We can see evidence of the appropriation of Persian culture in much of the artwork and design of this particular gift book. The front cover’s script (see fig. 1) is reminiscent of Persian writing, presumably with the intent of exotifying the piece and creating an appeal to readers. Were this text in the original Persian script and language with a translation beneath, it would read more as an act of cultural appreciation, in my opinion. However, instead of aiming to involve the reader in Persian culture by explaining it to a non-Persian audience, this book commodifies it, uses its language as a stylistic choice, and presents its words and story as a novelty. These visual and text assessments of the Rubáiyát tie closely to Black’s description that “The most frequent image critics use to discuss the Rubáiyát, the gem…encapsulates the poem’s problematic status” (6). These attempts to make the book pretty and make it appeal to readers emphasize the way that Persian culture is appropriated for the benefit of their interest and desire for ownership. As Black later puts it, “this poem’s value becomes inseparable from its pretty, crafted, possessable diminutiveness” (61). This idea of making the book “palatable” to western audiences diminishes its value as a piece of artwork, both in a visual sense and in a sense of the text’s content.

We can see more appropriation in the artwork of this book. Much of the colored illustrations feature white women who have light-colored hair and fit very obviously European beauty standards (see fig. 2 and fig. 3), yet these women are featured in decidedly non-European clothing, and alongside men who do appear to be from the region of the poem’s origins. This obvious intent to appeal to European preferences and ideologies around women, paired with the Renaissance-esque stylistic choices of the artwork makes it very clear that this gift book, despite coming from a non-European culture, is very much for European and American audiences. The featuring of white women in a person of color’s cultural attire, particularly when inaccurately portrayed, cannot possibly be written off as not being cultural appropriation. A look at actual Persian women’s clothing from the time when the Rubáiyát was written shows that these clothing items are far from accurate depictions, and are far more sexualized than the actual culturally accurate clothing was. Thus, these women depicted partake in the commodification and sexualization of a culture they make little effort to understand or genuinely partake in. For example, in figure 2, we see a pale woman depicted in fitted, revealing clothing, wildly inaccurate to the cultural clothing of women in 12th century Persia. Additionally, her pale complexion, particularly placed next to a man of a darker skin tone who appears to be practically worshipping her, sends a message of valuing and worshipping whiteness as a beauty standard. These two elements together show a sexualization of the concept of a white woman in clothing that pretends to be Persian, of a costume that devalues the real culture it pretends to be from. This ties into the “exotically and erotically charged” (62) nature of Walter Benjamin’s collector, the desire to own this culture and make it something that appeals to an audience who does not care about actual Persian culture. Thus, once more, we see the exotification of Persian culture and the diminishing of it to a novelty which audiences could own.

It is notable that, despite the stylistic choices of the piece, there is still an appreciation for the core material and its messages. Though there is most certainly an element of Orientalism and appropriation, there is still, at the core of this gift book fascination, an appreciation for the art and words of a Persian man. This is telegraphed by the interest of this particular edition in showing multiple translations and interpretations of the poem (see the text of fig. 4), and the overall fascination with this particular piece of literature and its existentialism. However, this does not minimize the evident desire to “own” a piece of Persian culture and art that undercurrents this interest in gift books. Additionally, it is a given that these translations cannot possibly be fully accurate to the original texts. The multiple versions of these translations make this much very clear, and Black cites multiple times where FitzGerald made changes to the original poem, such as when he “prettified the lines, omitting the reference to the flesh (the thigh of lamb) and offering in its stead a book of verses” (62). Thus, here we see the softening of the text, the decision to change the very being of the poem to accommodate western tastes, creating a piece of art where it is impossible for any aspect to be wholly untouched by colonialism or cultural appropriation.

Overall, as one can see, there is a significant amount of cultural appropriation and Orientalism present in the culture of Rubáiyát gift books. It can be seen through the design elements of the books themselves, the depiction of white women in a narrative that pertains to Persian culture, and the inaccurate portrayal of historical Persian clothing that these women are dressed in, harkening much more strongly to Greek and Renaissance artworks than to Persian artistry. Although there is an element of interest in the original text and works of a Persian writer present, it is important to be aware of the problematic, Orientalist nature of many of these publications, and to acknowledge this fact when assessing copies and the history of the text.

Sources Cited

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit : Victorians and Their Museums. Charlottesville, University Press Of Virginia, 2000.

Khayyam, Omar, et al. Rubaiyat. New York, Thomas Y Crowell Company, 1935.