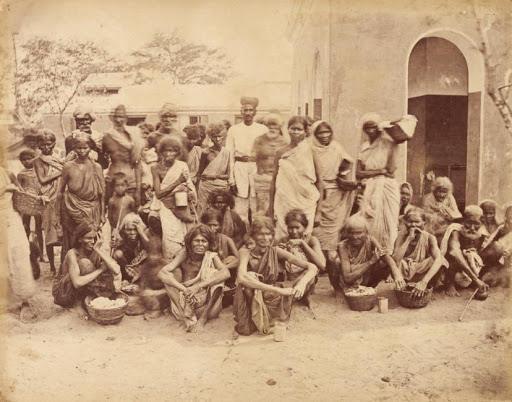

In southern and western India, there was a large-scale crisis in which there was a scarcity of food and around six to eleven million people died. The cause of this, besides starvation, is due to increased population, increased grain prices, lack of railroads, and unfair distribution of wealth and power. In 1876, a monsoon occurred in the Deccan plateau where there was a persistent struggle for food; this did not help the peasant cultivators who were already in debt. Additionally, these cultivators dug themselves a deeper hole by selling cattle, farm tools, and land. Then, a significant drought occurred in 1877 in which cultivators lost all of their resources and eventually lost their incomes. Only the wealthy were able to purchase the increased grain prices and continue bringing in capitol. Since crops became cash crops, farmers lost additional money due to the decline in demand for cotton in India and increase in demand for cotton in America. That being said, India was losing a lot of business while the Americans were progressively gaining it. Furthermore, the government was not allowed to intervene and lower the prices of food because it would create more debt for them. However, the government was not the only group that had no empathy for the lower and middle class, “grain merchants, in fact, preferred to export a record 6.4 million cwt. of wheat to Europe in 1877-78 rather than relieve starvation in India” (Davis, pg. 32). Lord Robert Bulwer-Lytton, a former Viceroy of India and diplomat, supported the Indian government’s refusal to intervene in the grain markets. This is because he believed that “he was in any case balancing budgets against lives that were already doomed or devalued of any civilized human quality” and stated that the Indian population ‘“has a tendency to increase more rapidly than the food it raises from the soil”’ (Davis, 32). He believes that engaging in a famine relief program would increase the poorer population and would bankrupt India. Moreover, he supported a laissez-faire approach and believed that free and abundant private trade provided by the government was not obtainable (Frederickson). Another reason for increased deaths in India was due to malaria and cholera. According to Lord George Hamilton, Under-Secretary of State for India, stated “‘the population of the district now affected by famine was probably the densest in the world… nearly double the density of the population of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland”’ (Fredrickson). Lastly, India’s inability to assist the famished added to the millions of deaths within the country, and in turn created a global problem. Millions of more people were dying because the drought extended to different countries, but India was hit the hardest.

Works Cited

Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World. United Kingdom, Verso, 2001.

EDGERTON-TARPLEY, KATHRYN. “Tough Choices: Grappling with Famine in Qing China, the British Empire, and Beyond.” Journal of World History, vol. 24, no. 1, 2013, pp. 135–176. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43286248. Accessed 2 Nov. 2020.

Frederickson, Kathleen. “British Writers on Population, Infrastructure, and the Great Indian Famine of 1876-8.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].