This is where you will add your timeline events.

Timeline

Table of Events

| Date | Event | Created by |

|---|---|---|

| 14 Jul 1789 | Fall of the BastilleThe Storming of the Bastille was the first openly violent event that was a part of the French Revolution, occurring on July 14, 1789, with its fall becoming an important symbol in the revolution. The Bastille was an armory, fortress, and political prison in Paris, and was seen by the revolutionaries to be a symbol of the monarchy’s abuse of power, as they believed the cost to maintain the fortress was far higher than the fortress’ worth. Originally, the reason for attacking the Bastille was because of the gunpowder that had been moved in there the day before the attack, but shifted into freeing the rumored multitude prisoners that were believed to have been imprisoned unjustly (Sutherland 2). The civilian insurgents vastly outnumbered the soldiers that were stationed at the Bastille, and eventually forced the soldiers to surrender. The commander in charge of the forces at the Bastille, Bernard-René Jourdan de Launay, was killed, and was subsequently beheaded and his head put on a pike. British newspapers received the news regarding the Storming of the Bastille within two weeks of the event, and were split in a way that about half were in support of the French government and the other half were in support of the Third Estate, being reflected in how they reprinted the news (Schürer 8, 26). This event also helped to found of the fear of strikes, unions, and working class mass-revolts in English factory owners in the 18th century, showing them what could happen if the working class, who clearly outnumbered them in England like they did during the Storming of the Bastille, all became of one mind. Schürer, Norbert. “The Storming of the Bastille in English Newspapers.” Eighteenth-Century Life, vol. 29, no. 1, Winter 2005, pp. 50–81. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1215/00982601-29-1-50. Sutherland, Donald (Donald M. G. .. “The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom (Review).” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 30, no. 1, May 1999, pp. 123–125. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip&db=edspmu&AN=edspmu.S1530916999101239&site=eds-live&scope=site. |

Cameron Evans |

| circa. The start of the month Sep 1793 to circa. The middle of the month Jul 1794 | The Reign of TerrorThe Reign of Terror was a tragic period of time during the French Revolution. The exact start date is a bit of a debate. Some historians say that the September Massacres, when a series of prisoners were murdered in 1792, marks the beginning while others argue it back in 1789. Either way, everyone knows that Maximilien Robespierre had a large amount of influence over the events during the Revolution. Robespierre was known as the Incorruptible because he was too moral. People of the time had mixed opinions about him. Some saw him as a great leader while others swore he was the devil. He ordered executions, mass incarcerations, and just fear in general. There are 16,594 total recorded death sentences during this time. There were even more people given jail sentences. The 22nd Law Prairial gave him the unnecessary ability to convict anyone of a crime against the Revolution. This power only led to an increase in deaths. In addition to the executions, news outlets were not even able to show how much damage he was doing because they were heavily censored to protect Robespierre. Despite all of the fear caused by this one man, a group of rebels formed to take him out of power. This plan is better known as the Thermidorian Reaction. The group overcame the Committee of Public Safety, made to prevent internal rebellion, and arrested Robespierre. With the fall of Robespierre in 1794 the Terror also officially ended, but the effects were felt for generations. Youtube video with more information: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wOuA-u6Me7o Censer, Jack R., “Historians Revisit the Terror-Again.” Journal of Social History, vol. 48 no. 2, Oxford University Press, 2014. doi:10.1093/jsh/shu077. Fairfax-Cholmeley, Alex. “Reliving the Terror: Victims and Print Culture during the Thermidorian Reaction in France, 1794–1795.” Wiley-Blackwell, 2019, file:///Users/katiehudnell/Downloads/Lit%20in%20Eng%202/Timeline%20source.pdf. Hitchcock, James. “Saved Through Fire: France’s Reign of Terror & the Witness of the Church Militant.” Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, vol. 31, no. 6, Nov. 2018, pp. 26-33. EBSCOhost, http://web.b.ebscohost.com.proxy.library.kent.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=c077dfe4-79b5-40b3-af35-640a3f7fa738%40pdc-v-sessmgr05. McLetchie, Scott. “Maximilien Robespierre, Master of the Terror.” Brace & Co., 1947, http://people.loyno.edu/~history/journal/1983-4/mcletchie.htm#22.

|

Katie Hudnell |

| Jul 1832 | The Reform Act of 1832The Reform Act of 1832, or “Great Reform Act,” was an electoral reform bill that reshaped the way Members of the House of Commons were elected to office. Although Members of Parliament were technically elected prior to 1832, limitations on who could vote (only propertied men) and haphazardly drawn electoral district lines meant that a small number of aristocratic elites either held or controlled the majority of seats in both parliamentary houses. Bribery was rampant, and the lack of a secret ballot allowed campaigners to put pressure on voters. By 1830, massive public outcry against the “rotten” electoral system (combined with ruling-class fear of revolutionary uprising like the one that had just taken place in France) put enough pressure on the government to act. The Tory-dominated House of Lords held out until 1832, when, faced with riots in the streets of Bristol and other cities around the country, King William IV threatened to create new Whig members of the nobility by royal decree and add them to the House of Lords. The House of Lords caved and passed the Reform Act, which created new electoral districts to more accurately represent population, introduced voter registration to prevent fraud, and made all male householders living in homes worth at least 10 pounds per year eligible to vote. While the actual changes created by the Reform Act were moderate—even after the Act, only about 10 percent of the population could vote—the Act revealed the limits of the power of the House of Lords and laid the groundwork for a series of incremental reforms that defined the Victorian period. Berman, Carolyn Vellenga. “On the Reform Act of 1832.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 27 September 2020. |

Jennifer MacLure |

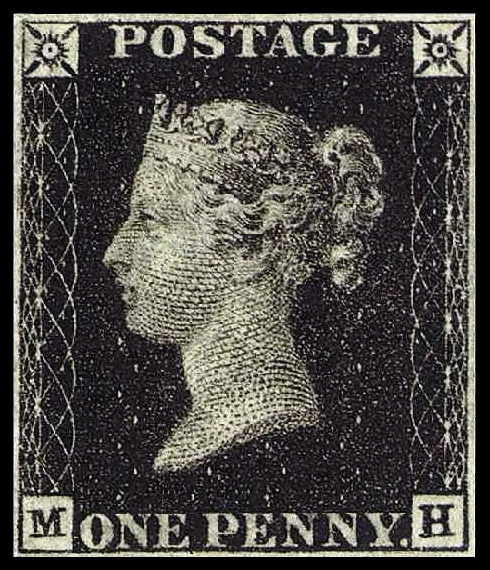

| circa. 1839 to circa. Winter 1840 | The Penny PostBefore the Penny Post, letter writing and postage was vastly more of an expensive and strenuous ordeal. According to Nestor in “New Opportunities for Self-Reflection . . .”, the cost of postage from London to Edinbburgh could total “the better part of a day’s wages for some” (5). Therefore, communication through letters was a luxury only the more privileged could afford to do on a consistent basis. To add to this, the cost of postage pre-reform was to be paid by the recipient rather than the sender. For those less privileged, especially women, they had to rely on their wealthy relatives and friends to deliver their correspondences to them, creating a barrier of sorts of communication between those of higher and lower socio-economic privileges. These high prices and the subsequent inaccessibility of communication through letters for the lower classes resulted in public outcry for postal reform, for which Queen Victoria was a proponent of (Golden). By 1840, the Penny Post was introduced nationwide in England, through Queen Victoria’s Postal Reform Act of 1839. The induction of the national Penny Post allowed for vast change in communication; first, the sender would pay the cost of the postage. This way, those without direct access to finances could still easily receive correspondence. Second, the cost that was paid could be as low as one pence (thus the name of the Penny Post). For the first time, the price of postage was so low that those previously without the resources to send and receive letters pre-reform finally had a new, more simple avenue for communication. Similar to how the advent of the internet, social media, and cell phones revolutionized communication in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the Penny Post allowed for broad communication throughout Victorian England.

Nestor, Pauline. “New Opportunities for Self-Reflection and Self-Fashioning: Women, Letters and the Novel in Mid-Victorian England.” Golden, Catherine J. Posting It: The Victorian Revolution in Letter Writing. University Press of Florida, 2009. Images from: |

Alexander Rienerth |

| 1845 to 1852 | Potato Famine in IrelandAround 1845, Ireland was hit with crop failure that deeply impacted them for years to come. The Irish population heavily relied on the potato crop for their livelihoods, so when the potato blight spread to their crops, they were thrown into a devastating famine with disease and starvation (Powderly “How Infection Shaped History”). The potato was a versatile crop being able to thrive in less desirable soil and providing sufficient nutrients for sustenance (Powderly). The potato blight affected more countries than just Ireland, however, Ireland was hit the hardest due to their “disproportionate dependency” on the potato, and growing only one species of the potato was also a problem because all their crops were affected rather than just one of several (Powderly). Ireland was not the only country to suffer from crop failure and famine, however, what made their famine such a devastating one was the political response of Britain who ruled Ireland at the time. The political atmosphere surrounding the potato famine in the 1840s was very complex and muddled with prejudices against the Irish people (Scholl “Irish Migration to London During the c.1845-52 Famine”). The British people in positions of power felt the Irish people deserved what they got and any relief they gave to Ireland was “exposing Britain to danger and expense” (Scholl). Despite the blame for the devastation of the Irish potato famine being placed on Britain, as many as one million Irish people migrated to Britain (in addition to Australia and North America) according to Scholl. The impact of the potato famine on the Irish population was catastrophic with an estimated range of 800,000 to one million deaths (Scholl). Dr. Powderly effectively illustrates the lasting effects of the famine on the Irish people even today: Governmental indifference, neglect, or deliberate inaction all contributed to the death toll of the Irish Famine. It was fitting, therefore, that 150 years later, the British Prime Minister, Tony Blair, apologized for the role played by the British Government. As he appropriately said, The famine was a defining event in the history of Ireland and Britain. It has left deep scars. That 1 million people should have died in what was then part of the richest and most powerful nation in the world is something that still causes pain as we reflect on it today. Those who governed in London at the time failed their people through standing by while a crop failure turned into a massive human tragedy.

Works Cited Powderly, William G. “HOW INFECTION SHAPED HISTORY: LESSONS FROM THE IRISH FAMINE.” Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, American Clinical and Climatological Association, 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6735970/. Scholl, Lesa. “Irish Migration to London During the c.1845-52 Famine: Henry Mayhew’s Representation in London Labour and the London Poor.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH]. |

jessica Poling |

| circa. 1846 | 1846 Repeal of the Corn Laws

COVE Timeline Assignment: 1846 Repeal of Corn Laws The British Corn Laws, or laws that regulated imported grains and food, were influenced by both economic and political conditions in Britain. The purpose of the tariffs were to keep people from buying forgien corn products and, in turn, force people to buy domestic corn products. This was meant to stimulate Britain's economy by enforcing domestic industry practices; it was also enacted to heavily favor the rich landholders who were invested in farmland production. The Corn Laws would not allow foreign corn into Britain unless domestic corn reached a price of 80 shillings per quarter (Vamplew 3). These laws offered a “significant degree of protection to British cereal producers” (Vamplew 11) who made huge profits from grain production. Landowners, seizing the majority of monetary profit, also retained much of the political power at the time; the act of voting was reserved for those who owned land. Thus, the beneficiaries of the Corn Laws were not the common people who were forced to buy grain at an absurdly high price, but the few lucky enough reap the benefits.

While Britain's common people suffered from poverty, starvation and unsanitary living conditions, they were upset by the increasing price of grain products. Many had to quit their jobs because they were ill or they needed to take care of family members; those who did earn a wage used most of it to buy grain products to survive. The middle class was desperate for reform-- not wanting to suffer like those impacted by Irish in the Irish Potato Famine-- and wanted representation in their government. Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey, author of From the Corn Laws to Free Trade: Interests, Ideas, and Institutions in Historical Perspective, writes “In sum, repeal was an attempt to moderate the mounting pressures for parliamentary reform: by satisfying the middle class industrialist with repeal, the drive to gain control of parliamentary seats would cease, and, moreover, the working class Chartist movement (seeking more radical reform of Parliament) would lose momentum” (16). The repeal of the Corn Laws was a motion intended to “settle down” the middle class by lowering the cost of grain products and thus progressing to a free market economy.

In addition to political reform, the repeal of the Corn Laws may have been the aftermath of a growing population; Betty Kemp, author of “Reflections on the Repeal of the Corn Laws” writes, “The simplest argument for the repeal of the Corn Laws is that the rapid growth of population' in the nineteenth century, which made it necessary to import increasing quantities of wheat, also made it un- justifiable to tax those imports” (3). Thus, a booming need for more materials lead to the repeal of the Corn Laws. This repeal, led by Sir Robert Peel, was a victory for the middle class (Kemp 2) and “the final triumph of the Free Trade move- ment” (Thomas 2) which sought to lower prices on grain and provided the economy with various trade options. Supplemental Material

Works Cited Kemp, Betty. "Reflections on the Repeal of the Corn Laws." Victorian Studies 5.3 (1962): 189-204. Schonhardt-Bailey, Cheryl. From the corn laws to free trade: interests, ideas, and institutions in historical perspective. Mit Press, 2006. Thomas, J. A. "The Repeal of the Corn Laws, 1846." Economica 25 (1929): 53-60. Vamplew, Wray. "The protection of English cereal producers: the Corn Laws reassessed." The Economic History Review 33.3 (1980): 382-395. |

Rebecca Cybulski |

| circa. 1847 | Ten Hours ActThe history topic I chose to cover was The Factory Act, also known as the Ten Hours Act of 1847. From the United Kingdom Parliament, the act was put into place to limit the number of hours women and children (ages 13-18) could work. It established that said peoples could only work 10 hours per day in textile mills. There were two different sides to this act: the anti-regulation group, led by Ashworth and Greg, and the pro-regulation group, led by Ashley. When discussing why people and some mill owners were pro-act, it says, “A possible reason is that there is evidence supporting the view that it was in the interest of all employers’ to curtail labour beyond a certain point (Toms, 10)”. There is also claim that there were other reasons for the act, stating that it “increase the cost of production of many of the smaller textile mills, thereby causing them to curtail their output (Toms, 10)”. Those pro-act had views that supported both their businesses, as well as providing a more reasonable working day for their workers. The anti-regulation group held other views on the act. The group claimed that it was seen to be as a threat to the owners (Michie). Even with the opposers, the Factory Act was established and was said to have helped shaped society, as well as, “imagining a wider field in which individual rights would be granted and protected (Michie)”. Michie, Elsie B. “On the Sacramental Test Act, the Catholic Relief Act, the Slavery Abolition Act, and the Factory Act.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. Accessed 12 Oct. 2020. The National Archives. “1833 Factory Act.” The National Archives, The National Archives, 1 July 2020, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/1833-factory-act/. Web. Accessed 12 Oct. 2020. Toms, Steven. “‘Cold, Calculating Political Economy’: Fixed Costs, the Rate of Profit and the Length of the Working Day in the Factory Act Debates, 1832-1847.” MPRA Paper, 2014. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip&db=edsrep&AN=edsrep.p.pra.mprapa.54408&site=eds-live&scope=site. Web. Accessed 12 Oct. 2020. “The Working-Class During the Industrial Revolution: Growth & Ideologies.” Study.com, June 2014, study.com/academy/lesson/the-working-class-during-the-industrial-revolution-growth-ideologies.html. Web. Accessed 12 Oct. 2020. |

Mai-Ling Francis |

| May 1851 to Oct 1851 | The Great ExhibitionThe Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, or the Great Exhibition for short, was an event that opened its doors on May 1, 1851. The Great Exhibition was brought about to showcase the “industry and ingeniousness of various world cultures” and to also educate the general public about the technologies that were on display (Audrey, para. 1). The majority of the exhibits that were shown had to deal with the British, about half or so, and the rest of the exhibits were set on display by other cultures. The Great Exhibition was accessible from May to October of 1851. Queen Victoria opened this exhibition and held it in a structure that was built for this event – the Crystal Palace. The Crystal Palace was located in Hyde Park, London. The palace covered 26 acres and had over 4,000 tons of iron, over 200 miles of gutters and sash bars, and thousands and thousands of feet in wooden flooring as well as glass. The Crystal Palace resembled the “shopping arcades of Paris and London” (Audrey, para. 3). The entirety of the space was used to educate and entertain the public that wanted, and could afford, this exhibition experience. The first day the Great Exhibition was opened, over 25,000 people attended. Overall, over six million came to the exhibition from May to October of 1851 and many of these guests attended the exhibition more than once (Queen Victoria included). When the doors first opened, the entrance fee was about five shillings or above. But as it became clear that the exhibition was vastly popular, the price was lowered to one shilling so that the entirety of the general population could attend. After this change was made, many feared that the general population would scare away the wealthier class, but the Great Exhibition was so popular that the numbers never even dropped! Although this was a popular event and aimed to showcase the goods and technology of the time, no items were actually for sale in The Crystal Palace itself. The items were just there to showcase the new and upcoming things regarding goods and technology. The Great Exhibition steered the population towards window shopping and pushed the consumers towards consumption even though nothing was immediately for sale. The space that surrounded the population had them looking from object to object with nothing but admiration. The consumers were too dazzled by their environment to pay much attention to the idea that they wouldn’t immediately be able to leave with one of the lavishing items. Jaffe, Audrey. “On the Great Exhibition.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 25 October 2020.

|

Abigail Bigelow |

| Spring 1853 | The Vaccination Act of 1853The Vaccination Act of 1853 was a law that was passed in England in response to the overwhelming smallpox epidemic. Smallpox was one of the most common causes of death in Britain at the time and had a mortality rate of 30%. Those who survived were often blinded and/or scarred (Victorian Health Reform). This act was a part of a series of laws to make vaccinations mandatory for the public. The 1853 act made it compulsory for all children to be vaccinated within the first three months of their lives to protect them against smallpox (Wolfe and Sharp). If the parents of these children refused to comply with the law, they were subject to pay a fine and could even spend time in jail. Immediately after the passing of the 1853 law, resistance to vaccinations began among the public. Violent riots occurred in Mitford, Ipswich, Henley, and various other towns (Wolfe and Sharp). That same year an anti-vaccination group, the Anti-Vaccination Leauge, was founded in London and provided an outlet for those who were opposed to the new laws. There were many reasons why people were opposed to receiving mandatory vaccinations. Many people were afraid that the vaccines were unsafe and felt that they were unnecessary. Others found the fact that the vaccines were compulsory to be a major government interference (Victorian Health Reform). While not everyone was against the thought of these new vaccinations, those who were opposed were much more vocal and aggressive about their dissent. To truly understand the role of science in society at the time, it is important to be aware of the range of views that the public held on this topic. Victorian Health Reform. (n.d.). The National Archives. Retrieved November 1, 2020, from https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/victorian-health-reform/ Wolfe, R. M., & Sharp, L. K. (n.d.). Anti-Vaccinationists Past and Present. NCBI. Retrieved November 1, 2020, from |

Joanna Clair |

| The middle of the month Autumn 1853 to The end of the month Spring 1856 | The Crimean WarThe Crimean War was a battle that lasted from 1853-1856. It started when Russia threatened many European countries, such as Great Britain and France due to their desire to annex Turkey, which by then was known as the Ottoman Empire. This was especially troublesome for Britain, as Russia wanted to take over a country that was vital to their trading practices in eastern countries. This started an alliance between the Ottomans, British, French, and eventually Sardinia. This war helped the countries demonstrate the changes they put their militaries through: “developments in technology had the potential to alter radically the way in which war is fought; other changes, such as. . . the telegraph, would transform. . . how rapidly events in the East were viewed from the home front” (Markovits 1). The changes in military had helped gain wins for both sides, with Britain’s alliance ultimately winning the war. In addition to that, this was the first war to ever use such modern technology at the time, ranging from telegraphs to naval shells. Unfortunately, there were other problems in the war aside from casualties. There was much criticism regarding mismanagement during certain battles. These criticisms were made apparent during one such battle, known as the Charge of the Light Brigade. During the battle, there was a severe miscommunication error that sent the British “headlong into retreating Russian hussars, who were fleeing from their. . . encounter with the Heavy Brigade” (Danahay 3). This mistaken order had led to extreme casualties for British troops and with no real gains for both sides. As such, the Crimean War ended up being significant due to the technological military advances at the time and the mismanagement during certain battles. Bibliography Danahey, Martin. “‘Valiant Lunatics’: Heroism and Insanity in British and Russian Reactions to the Charge of the Light Brigade.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [2 November 2020]. Markovits, Stefanie. “On the Crimean War and the Charge of the Light Brigade.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH]. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Timeline-Crimean… https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Charge-Of-The-Li… |

Stephen Simone |

| Sep 1854 | John Snow's Cholera MapIn September 1854, England had to face its third cholera outbreak of the Nineteenth Century. The previous outbreak of 1848 had been absolutely devastating and reached epidemic status as it spread across England and Wales. People were wary of another outbreak, so when people started coming down with similar symptoms and dying in Soho, London, they feared the worst. John Snow was a doctor who lived relatively near Broad Street, the location of most of the new cases. Snow had been adamant in his belief that cholera was spread through water polluted with fecal matter after the 1848 epidemic, but he saw little support from his contemporaries, so he was determined to prove it once and for all. Snow worked together with locals of Broad Street like the Reverend Henry Whitehead to gain information on who became sick and died. Many locals were worried about giving up this information because of how the government had treated those who were sick in 1848, but they trusted Whitehead. Snow marked each case of cholera on a map he created to visualize the patterns of infection. By the end of the outbreak, there had been over 600 deaths. He traced every case back to a single pump on Broad Street that was polluted from the leaking cesspools of nearby houses. In some cases, different pumps in the neighborhood were geographically closer to affected people, but the Broad Street pump was a shorter and straighter walk. The locals also claimed the water from the Broad Street pump tasted better than any other pump in the area. Snow was not only looking for the people in the area who died from the polluted pump water. He was also looking for cases that did not fit the pattern. He found three such cases. First, the men who worked in the brewery on Broad Street did not get sick because they largely drank beer instead of water. Second, the workhouse that contained the poorest of the poor in Soho saw hardly any cases because they had their own water well to drink from. Third, an old woman who lived miles away in the neighborhood of Hampstead, London got sick along with her niece who lived with her. Snow discovered her family, who still lived on Broad Street, brought her water so she would not exhaust herself getting her own. Snow now had irrefutable evidence that this Broad Street outbreak was caused by the polluted pump, and he convinced many of his peers in the medical profession as well as the local authorities. Unfortunately, the locals did not believe him for years afterwards, so he had to appeal to the authorities to have the pump handle completely removed. John Snow is now considered a pioneer of epidemiology due to his data collecting and ability to visualize the patterns of infection on his famous map. His findings would also go on to support arguments for a better sewer system in London which greatly improved the health of the city and the people living in all of its neighborhoods. Gilbert, Pamela K. “On Cholera in Nineteeth-Century England.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. Accessed 14 Oct. 2020. John Snow, Cholera, the Broad Street Pump; Waterborne Diseases Then and Now. 2018. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip&db=edsgvr&AN=edsgcl.7433400015&site=eds-live&scope=site. Accessed 15 October 2020. Video for more information: Goodman, Alyssa. “John Snow and the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak.” Youtube, Uploaded by HarvardX, 19 April 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lNjrAXGRda4. Accessed 14 October 2020. |

Annabeth Suchy |

| The end of the month Autumn 1857 to The end of the month Winter 1857 | 1857 Financial CrisisIn 1857, Britain and the United States shared a financial crisis that began in the US and spread overseas, and which is “generally regarded as the first world-wide Financial Crisis” (Shakinovsky). During the first 7 years of the 1850s, Britain was experiencing a period of extreme profitability and affluence. Their export market had expanded by 66% as innovations in the form of trains, steamships, and telegraphs alongside colonial expansion drove the economy to new heights. In the United States, the crisis began on 24 August, 1857, with the fall of the Ohio State Life and Trust Company, and at its peak the panic resulted in the failure of 1,415 banks in the United States. England’s economy was heavily intermixed with the United States’, and while the spread of the panic was delayed, it did eventually prove contagious. Glasgow and Liverpool, the two cities most involved in American trade, were the first to feel the effects, with the first domino being the fall of the Liverpool Borough Bank on 27 October. Basically, the banks had more loans, debts, and deposits than they had currency and bullion reserves, so when people lost trust in the banks and withdrew their money, the banks found their currency reserves depleting and had to close their doors. To combat this panic, the British government suspended the Bank Charter Act of 1844, which had required banks to have bullion (gold and silver reserves) to back up all the currency in circulation. The idea of the act was that it would prevent risky speculation on the part of the banks and investors, but the booming markets and economy of the 1850s had encouraged risky ventures, which proved vulnerable as soon as the market contracted due to the panic. Suspending the act allowed for more paper currency to be issued, allowing the banks to have sufficient currency on hand. This suspension took some time to be effective, but it did eventually succeed in calming the panic and the crisis was declared officially over on December 24, 1857. The crisis threw into stark relief the perils of the capitalist system and the growing pains of currency systems, and the issues with tying currency to physical bullion reserves amidst the growing British and world economies. Source: Shakinovsy, Lynn. “The 1857 Financial Crisis and the Suspension of the 1844 Bank Act.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation, and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. http://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=lynn-shakinovsky-the-1857-financial-crisis-and-the-suspension-of-the-1844-bank-act. Accessed 2 November 2020. |

Joseph Rush |

| Jul 1866 | Transatlantic Cable EstablishedThe first telegraph systems were established within the United States and Great Britain in the 1840’s and soon after there was a desire to spread this communication (Israel & Slotten). Cyrus W. Field was a young millionaire in New York who “organized the New York, Newfoundland, and London Electric Telegraph Company” in collaboration with Fred N. Gisborne who received “an exclusive 30-year right to construct telegraph lines in Newfoundland” (Babe). Field was able to establish the American Telegraph Company which controlled the “telegraph lines along the eastern seaboard”, but he “was unable to convince American investors to back the Atlantic cable” (Israel & Slotten). As a result of the lack of funds, Field went to London with Samuel F. B. Morse, who invented the first American telegraph. The pair formed the Atlantic Telegraph Company in 1856 and were able to gain funds and support from the British government for the Atlantic cable and began construction in 1857 (Israel & Slotten). After a few failed attempts where the cable broke while being laid, Field succeeded in creating and laying a cable in August 1858 and “arranged for Queen Victoria to send the first transatlantic message” to President James Buchanan (Babe). However, after this celebratory exchange the cable snapped after only being in use for three weeks (Babe). Field was unable to gain financial support to reconstruct in America because of the Civil War, so he again returned to British investors (Israel & Slotten). 2700 miles of cable were needed to cross the Atlantic, and this cable was laid out by the large cargo ship, The Great Eastern and the British “war steamer Terrible [was] to accompany the expedition” (By Telegraph). The Transatlantic connection was finally restored in late July 1866, and the cable “remained in service for nearly a century” (Babe). The Transatlantic cable was revolutionary for the time and “opened up a new era in global communications” because “the Atlantic cable allowed for near-instantaneous communication” (Israel & Slotten). Not only did this cable change the way that news and communication travelled, but it also was “significant as a technology crucial in the development of the modern process of globalization” (Israel & Slotten). Works Cited Babe, Robert E. "transatlantic cable." The Oxford Companion to Canadian History.: Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference. Date Accessed 1 Nov. 2020 https://www-oxfordreference-com.proxy.library.kent.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195415599.001.0001/acref-9780195415599-e-1559 "By Telegraph." Boston Daily Advertiser, 7 June 1866. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.proxy.library.kent.edu/apps/doc/GT3006420565/NCNP…. Accessed 1 Nov. 2020. Israel, Paul, and Hugh Richard, Slotten. "Atlantic Cable." The Oxford Encyclopedia of the History of American Science, Medicine, and Technology: Oxford University Press, 2015. Oxford Reference. Date Accessed 1 Nov. 2020 <https://www-oxfordreference-com.proxy.library.kent.edu/view/10.1093/acr…;. |

Emily Vahs |

| 1870 | The Married Women's Property Act of 1870Summary of the Act: The Married Women’s Property Act was put forth in 1870 and later repealed in 1882 by a different property act. This act gave women married after 1870 the right to own and control various forms of property. While the act seemed to be about protecting the rights of women in a male governed society, recent historians have come to the conclusion that this act more so protected newly married couples from fraud. The act protected young women’s assets before entering into a marriage. The women who most benefited from this act were single and widowed women. Despite this not creating equal rights for women, it did make a step in the right direction for women. Before this, once women were married all their property and any sort of wealth belonged to their husband. In addition to becoming the husband’s property, that property isn’t returned to the wife upon her husband’s death but can be instead willed away to someone else. Another part of before the act, stated that a husband could sell or give away the wife’s property at any point in their marriage. Then, however, it couldn’t be willed away. Moral of it, married women had no control over their property once they were married. This act was important in protecting women from losing their livelihood and personal goods. A married woman could keep her earnings separate from her husband’s affairs. She could also have control over her own personal property like bank accounts, public stock and funds, and shares. Finally, this also meant she could have a more active role in society and her own life. Sources for summary: Combs, Mary Beth. “‘A Measure of Legal Independence’: The 1870 Married Women's Property Act and the Portfolio Allocations of British Wives.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 65, no. 4, 2005, pp. 1028–1057. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3874913. Accessed 2 Nov. 2020. Griffin, Ben. “Class, Gender, and Liberalism in Parliament, 1868-1882: The Case of the Married Women's Property Acts.” The Historical Journal, vol. 46, no. 1, 2003, pp. 59–87. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3133595. Accessed 2 Nov. 2020. Supplemental Material: This is a clip from the newest Little Women that features Amy talking to Laurie about how marriage restricts her ability to own property. She states that her money would become his and if they had children, the children would also be his. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0D8nRpJsQlk |

Madeline Aladich |

| 9 Aug 1870 | Elementary Education Act of 1870The Elementary Education of 1870, also known as The Forster Act after the liberal Parliament member William Forster, was a reformation act that required national compulsory education for children ages five to 13 in England and Wales. The Act was one of the first passed by Parliament that promoted compulsory education and its goals were to provide free, compulsory, nonreligious education for children where schools were not available and to reduce the amount of child labor in England and Wales. Many more acts dealing with compulsory education were passed between the years 1870 and 1893 (Dalgleish). The Elementary Education Act covered reforms for many aspects of a child’s education, including public funding for schools, regular inspections by the school board to ensure proper educational spaces as well as a high quality of schooling, and educational financial support from parents who are able. The Act also institutionalized a religious separation from public education, stating that religious teachings be non-denominational and the Act also allowed parents to decide whether or not to withdraw their children from any religious schooling. The Act also allowed women to be elected on school boards as reforms for women’s rights were also being promoted through the Married Women’s Property Act of the same year (Tucker). The main backlash against the Elementary Education Act dealt with religious pressures and uncertainty of funding. With the general advancement away from education intersecting with religion, the Church of England was afraid of a loss of control over the education of Great Britain while some specific schools also wanted to continue to have denominational teachings. The Educational Act resolved these issues by still allowing schools to choose to teach religion but also allowing parents to withdraw students from these teachings as well as not favoring one denomination of Christianity over another. Another fear that arose from the Act was the uncertainty of mass education and state subsidies (Dalgleish). The Act then required parents who could afford to pay for their child’s schooling to do so while those who could not would be supported through state subsidies. Dalgleish, Walter. A Plain Reading of the Elementary Education Act. London, John Marshall & Co., 1870. Tucker, Herbert F. “In the Event of a Second Reform.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net, June 2012, Web. Accessed 2 November 2020. |

Chloe Holm |

| 1876 to 1878 | The Great Famine in IndiaIn southern and western India, there was a large-scale crisis in which there was a scarcity of food and around six to eleven million people died. The cause of this, besides starvation, is due to increased population, increased grain prices, lack of railroads, and unfair distribution of wealth and power. In 1876, a monsoon occurred in the Deccan plateau where there was a persistent struggle for food; this did not help the peasant cultivators who were already in debt. Additionally, these cultivators dug themselves a deeper hole by selling cattle, farm tools, and land. Then, a significant drought occurred in 1877 in which cultivators lost all of their resources and eventually lost their incomes. Only the wealthy were able to purchase the increased grain prices and continue bringing in capitol. Since crops became cash crops, farmers lost additional money due to the decline in demand for cotton in India and increase in demand for cotton in America. That being said, India was losing a lot of business while the Americans were progressively gaining it. Furthermore, the government was not allowed to intervene and lower the prices of food because it would create more debt for them. However, the government was not the only group that had no empathy for the lower and middle class, “grain merchants, in fact, preferred to export a record 6.4 million cwt. of wheat to Europe in 1877-78 rather than relieve starvation in India” (Davis, pg. 32). Lord Robert Bulwer-Lytton, a former Viceroy of India and diplomat, supported the Indian government’s refusal to intervene in the grain markets. This is because he believed that “he was in any case balancing budgets against lives that were already doomed or devalued of any civilized human quality” and stated that the Indian population ‘“has a tendency to increase more rapidly than the food it raises from the soil”’ (Davis, 32). He believes that engaging in a famine relief program would increase the poorer population and would bankrupt India. Moreover, he supported a laissez-faire approach and believed that free and abundant private trade provided by the government was not obtainable (Frederickson). Another reason for increased deaths in India was due to malaria and cholera. According to Lord George Hamilton, Under-Secretary of State for India, stated “‘the population of the district now affected by famine was probably the densest in the world… nearly double the density of the population of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland”’ (Fredrickson). Lastly, India’s inability to assist the famished added to the millions of deaths within the country, and in turn created a global problem. Millions of more people were dying because the drought extended to different countries, but India was hit the hardest. Works Cited Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World. United Kingdom, Verso, 2001. EDGERTON-TARPLEY, KATHRYN. “Tough Choices: Grappling with Famine in Qing China, the British Empire, and Beyond.” Journal of World History, vol. 24, no. 1, 2013, pp. 135–176. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43286248. Accessed 2 Nov. 2020. Frederickson, Kathleen. “British Writers on Population, Infrastructure, and the Great Indian Famine of 1876-8.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH]. |

Renee Regalbuto |

| 25 Aug 1883 to 27 Aug 1883 | Krakatoa Eruption of 1883Krakatoa, also called Krakatau, is an Indonesian island best-known for being the site of one of the deadliest volcanic eruptions in recorded history. In late August of 1883, after a few months of minor eruptions and substantial volcanic activity, Krakatoa blew its top in a spectacular and frightening display that destroyed two-thirds of the island. The ash began to fall on August 25, and two days later, four consecutive explosions sent tsunamis careening into the shores of Sumatra and Java, killing over 36,000 people. In addition, the third and most powerful explosion generated a sonic pressure wave that was heard 3,000 miles away, making it “the furthest-travelling audible sound in recorded history” (Thornton 1); the resulting air wave registered on barographs worldwide and was determined to have crossed the globe seven times (Symons 63). Effects The eruption of Krakatoa was one of the earliest examples of breaking international news, and it highlighted the capabilities of telegraphic communication as word of the event spread like wildfire. Carefully-documented local observations, both from Indonesia and around the world, provided invaluable data in examining the power, ash spread, and aftereffects of the eruption, and that marriage of informal with academic renewed public interest in scientific research. Krakatoa itself quickly became a centerpoint for much of that research; no life on the island survived the eruption, which provided scientists with a unique opportunity to witness ecological rebirth in the wake of such a catastrophic disaster. Furthermore, fumes released by the eruption into the atmosphere dropped global temperatures and led to record-high rainfall along the West Coast of North America. Ash blown skyward spread across the world via air currents, causing breathtaking – and occasionally alarming – sunsets across the world, some of which were captured by various artists, including William Ascroft. In fact, some researchers believe Edvard Munch’s famous painting The Scream features a sunset derived from Munch’s memory of a Krakatoa sunset (Olson 3). Morgan, Monique R. “The Eruption of Krakatoa (also known as Krakatau) in 1883.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 6 November 2020. Thornton, Ian. Krakatau: The Destruction and Reassembly of an Island Ecosystem. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1996. Print. Symons, G. J., ed. The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena: Report of the Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society. London: Trübner, 1888. Google Books. Web. 6 November 2020. Olson, Donald W.; Russell L. Doescher; Marilynn S. Olson (May 2005). "The Blood-Red Sky of the Scream". APS News. American Physical Society. Retrieved 6 November 2020. |

Emily Schinker |

| Apr 1895 to May 1895 | April 3, 1895- May 25, 1895: Trials of Oscar WildeOne of Literature's best authors Oscar Wilde went on trial for having an affair with a man and in this time being gay was a crime punishable by death. Before this trial Oscar Wilde was gaining popularity due to his playwrights, novels, and poems. Oscar Wilde was known for his amazing work and his flamboyant dress along with his cutting wit and eccentric lifestyle often put him at odds with the social norms of Victorian England. Oscar Wilde did, however, marry a woman named Constance Llyod and together had two sons named Cyril and Vyvyan. Oscar Wilde was hiding his sexualitty from the world and his family until he met a man named Lord Alfred Douglas who was a young (sixteen years younger) poet and aristocrat from Britian. The news about their relationship spread all over Britian like wild fire. Soon The British Government wanted to arrest Wilde right away for his homosexual acts however instead of running away he decided to sue the Marquess of Queensberry for defamation. This is when our trials offically begin! Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly known as Old Bailey was the location of the trials. During this trial Oscar Wilde got destroyed The trial went poorly for Oscar Wilde. His main problem was that the allegations about his homosexuality were true, and therefore he couldn't win the trial. However there were some things that they accussed Wilde of that didn't make sense such as: seducing 12 other young men to commit sodomy and the idea of homoerotic themes within his works. After three days of the court proceedings, Wilde’s lawyer withdrew the lawsuit. The British authorities saw this withdrawal as a sign of implied guilt and issued a warrant for Wilde’s arrest on indecency charges. The Britain’s Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 had criminalized all sex acts between men as “gross indecency.” (Sex acts between women were never made illegal in England.) His friends begged Oscar to flee Britian and head to France so he wouldnt face the trial for a second time. However, Oscar stayed and decided to attend the trial with no attempts of escape or denial. Oscar Wilde was tried for homosexuality on April 26, 1895. He pleaded not guilty on 25 counts of gross indecency. The trial ended with the jury unable to reach a verdict. Three weeks later, Wilde was retried. This time, Wilde was convicted of gross indecency and received two years of hard labor, the maximum sentence allowed for the crime. On May 25, 1895, Oscar Wilde was taken to prison. He spent the first several months at London’s Pentonville Prison, where he was put to work picking oakum. Oakum was a substance used to seal gaps in shipbuilding. Prisoners spent hours untwisting and teasing apart recycled ropes to obtain the fibers used in making oakum. |

Abby Feasel |

| Autumn 1899 to 1902 | 1899-1902 Anglo-Boer WarIn October of 1899 a war broke out in South Africa. The war would become known as the Anglo-Boer war. Oddly enough the war would frequently be called “The White Man’s War,” because the natives in the region had nothing to do with the conflict. The parties involved were Great Britain and its colonized regions (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) and two former British republics; the Free Orange State and Transvaal. The people in this region were called the Boer people and primarily consisted of Danish farmers who settled in the area in the 17th century. The Boers were very independent and essentially cut themselves off from mainland Europe. By 1850 the Boers subdivided into the Free Orange State and Transvaal. Relations between the Boer states and other British colonies were not good before the war began but the primary conflict that led to war in 1899 was over the control of the Transvaal gold fields in the Boer region. As more gold was found, an increasing number of ‘Uitlanders’ (foreigners) moved to the region. British representatives wished that the foreigners, primarily Europeans, would have the immediate right to vote in Transvaal elections. The British Empire saw this as a way to win back the separating territory and a good amount of gold. The Transvaal representative disagreed and war broke out in the area as British soldiers would not leave the area as requested by the Transvaals. The Anglo-Boer war is commonly known as Britain's Vietnam due to the Empire’s underestimation of the Boer peoples fighting ability. The British thought that the war would only last for a week, yet in fact the war lasted for over two years and thousands of people lost their lives, just like in the Vietnam war. Unfortunately the African natives, who had little to no involvement in the war, suffered thousands of casualties as they were forced into concentration camps by the British. The Anglo-Boer war was a tragic war, not only did the Boers lose their independence from the British, they also lost thousands of women and children from the camps. The war destroyed Boer towns and farms, but most catastrophic was the destruction of the Boer way of life. Works Cited: Canadian War Museum, Jerome Foldes-Busque. “Canada and the South African War, 1899-1902.” WarMuseum.ca - South African War - Boer War Maps, Canadian War Museum, www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/boer/boerwarmaps_e.html. “Case Name: Anglo-Boer: Britain's Vietnam .” Class\Work\Boerwar, American University of Washington D.C Trade Environment Projects, 27 Oct. 2016, web.archive.org/web/20161027014601/www1.american.edu/ted/ice/boerwar.htm. |

William Smith |

| The start of the month Winter 1901 | 1901 - First wireless communication across Atlantic oceanIt was once believed to be impossible to send a transmission about as far as 200 miles due to the curvature of the Earth. This assumption didn’t stop Guglielmo Marconi from trying, though. Guglielmo Marconi was an Italian inventor and engineer, born in Bologna, Italy. Growing up, Guglielmo had a very good education due to his family’s wealth. He had multiple tutors growing up and then went on to further his education at the Livorno Technical Institute and the University of Bologna. Guglielmo had a strong interest in electromagnetic waves. He began to build his own wave generating equipment, but no one of importance was interested in what he had to offer, so Guglielmo moved to London. At first, he was only able to send transmission up to one mile away, but after a year's worth of work after moving to London, he had built it up to 12 miles away. There were many people in London who were interested in supporting Guglielmo’s work, including the British Post Office and eventually, Queen Victoria. A year later, Guglielmo had been able to send transmissions across the English Channel. After this, he had quickly begun to gain popularity around the globe. Guglielmo wanted to continue improving his work. At the time, “many physicists argued that radio waves traveled in straight lines, making it impossible for signals to be broadcast beyond the horizon, but Marconi believed they would follow the planet’s curvature” (History.com, Editors). After failing to go at too far of a distance right off the bat, Guglielmo tried a shorter distance, from Cornwall to Marconi. Just barely, they were able to successfully send the transmission; they received the message a faint three-dot message, the letter “s”. This transmission was approximately 2,100 miles away and sent sparks flying in the process. This moment was a monumental step in history, but there was still a long way to go to completely understand electromagnetic waves, so Guglielmo continued to improve his work for the next 30 years. In 1909, he was awarded a Nobel prize in physics for his work alongside Ferdinand Braun. Not only did his work help the evolution of the radio, but it save multiple lives. “His company’s Marconi radios ended the isolation of ocean travel and saved hundreds of lives, including all of the surviving passengers from the sinking Titanic” (History.com, Editors). Works Cited History.com Editors. (2009, December 02). Guglielmo Marconi. Retrieved December 08, 2020, from https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/guglielmo-marconi Editors. (2010, February 09). First radio transmission sent across the Atlantic Ocean. Retrieved December 08, 2020, from https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/marconi-sends-first-atlanti… |

Paige Perkowski |

| The end of the month Spring 1916 | The Easter Rising in DublinThe Easter Rising in Dublin occurred on Easter Monday: April 24, 1916. The Easter Rising was an insurrection against the British government that wished for independence from Britain, and causally, to cut ties from obligations to serve Britain. By the end of the day important civic and private property, including the city’s post office, was seized by the rebel army of the Irish Republic. The Irish Republic consisted of three main factions: “the revolutionary fraternity of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Irish volunteers who opposed Ireland’s participation in Britain's imperial war, and the Irish Citizens Army (992). One of the leaders of the insurrection, Patrick Pearse, came down the post office steps after it had been seized in the early afternoon and proclaimed Ireland to be an independent republic. The Irish Citizens army was a worker’s militia formed in retaliation to the police brutality that had occured against striking unions three years prior on the infamous Bloody Sunday. Within the week the insurrection was suppressed and resulted in the death and injury of thousands. The leaders of the revolt were then executed—swaying public opinion towards the side of the rebellion as the leaders and their causes became martyred. Although the rebellion was initially unsuccessful in securing independence for Ireland, it’s resulting shift in public opinion against Britain marshal law and their rushed executions of suspected allies to the rebellion led to parliament members being elected who wished to establish a free republic. Eventually, a treaty was signed amongst Britain and Ireland that created the Irish Free State. Works Cited Arrington, Lauren. “Socialist Republican Discourse and the 1916 Easter Rising: The Occupation of Jacob's Biscuit Factory and the South Dublin Union Explained.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 53, no. 4, 2014, pp. 992–1010. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24701520. Accessed 6 Dec. 2020. History.com Editors. “Easter Rising.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 9 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/topics/british-history/easter-rising.

|

Madison Rheinheimer |

| 18 Jan 1919 to 28 Jun 1919 | Treaty of Versailles 1919The Treaty of Versailles was responsible for officiating the end of World War I which lasted from 1914 to 1918. The negotiations for this treaty started at the Peace Conference of Paris in January 1919. The end of the war saw the collapse of empires such as the Ottoman Empire, the Russian Empire, Austrian Empire and German Empire. This called for a new international order that was unlike anything in modern history. The Treaty of Versailles was the first treaty to be certified at the Peace Conference as it “tried to regulate the new international order that had emerged in Europe as a result of the outcome of World War I” (Keleher et al.). The four core delegates that put together this treaty were from France, Britain, United States and Italy. Their main and unanimous goal was figuring out the best way to stop Germany from causing any more harm. On June 28, 1919 the Treaty of Versailles was officially signed and the only great power not to sign it was the United States. What might be best known about this treaty is the harsh financial implications that it had for Germany. “The treaty’s provisions placed an extreme financial burden on Germany, thereby laying the foundation for another world conflict within a generation” (Keleher et al.). But there were also more implications for Germany such as a substantial loss of territory and disarmament.

Germans taking apart German war machines as part of the disarmament terms. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images) President Woodrow Wilson was hoping that the inclusion of the League of Nations in the treaty would be enough to keep the peace. However, the Treaty of Versailles created a lot of bitterness and desire for something more in the German people. It left the door open for someone like Adolf Hitler to gain control. Almost inevitably, the next world war started in 1939 just twenty years after the signing. Video of the Peace Conference of Paris Works Cited Keleher, Edward P., and Lewis L. Gould. “Treaty of Versailles.” Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2019. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip&db=ers&AN=89316411&site=eds-live&scope=site. |

Anna Hughes |

| The start of the month Dec 1921 to 1922 | 1921-22 - The Formation of the Irish Free StateDespite having a history of violence and distrust between the Irish Republic and England for years prior, from approximately 1916-1921, the Anglo-Irish war, or the Irish War of Independence, resulted in the formation of the Irish Free State. To conclude the war, the Anglo-Irish treaty was signed which declared the Irish Free State as an independent dominion similar to the then Dominion of Canada and the Commonwealth of Australia within the British Empire. Because of this treaty, the Irish Free State essentially had political independence, but the treaty included the Irish Free State as part of the British Commonwealth and included a heavily debated oath of allegiance that declared, “I….do solemnly swear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of the Irish Free State as by law established and that I will be faithful to H.M. King George V., his heirs and successors by law, in virtue of the common citizenship of Ireland with Great Britain and her adherence to and membership of the group of nations forming the British Commonwealth of Nations” (Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland). There was a three-step process for the transfer of power from British rule that included a provisional government, an assembly of constituents to approve a constitution, and the election of the first parliament (Corcoran). Exactly one year after the treaty was signed, December 6th, 1922, the Irish Free State government officially gained political control under the leadership of Prime Minister William T. Cosgrave. The next day, Northern Ireland decided to remain separate from the Irish Free State. As a newly independent state, the first few months and years of the Irish Free State suffered from many internal issues (Corcoran). Conflict broke out into what is considered to be the Irish Civil War between those who approved the Anglo-Irish treaty and those who refused to recognize the state as a free state. Because of this internal fighting, the government of the Irish Free State had a primary focus on Law and Order and therefore passed acts such as the Public Safety Act 1923, the Punishment of Offenders Act 1924, the Firearms Act 1924, and the Treasonable and Seditious Offences Act 1925 (Corcoran). Ultimately, those in favor of the Anglo-Irish treaty won the civil war, and the fighting wasted many resources in a newly independent dominion (Corcoran). Despite the internal political fighting; however, a government was established relatively quickly which is significant as the Irish Free State is still separated from Great Britain and the United Kingdom in the 21st century and remains a heavy political discussion among cultures, citizens, and religion. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nF3P7cdgU_I Works Cited Cocoran, Donal. "Public Policy in an emerging state: The Irish Free State 1922-25." Irish Journal of Public Policy, vol. 1, no. 1, Dec. 2009.

Great Britain and Irish Free State. treaties.un.org, https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/LON/Volume%2026/v26.pdf#pa…. Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland signed in London on December 6. 1921.

|

Meghan Williamson |

| The start of the month Summer 1928 | 1928 - Women Over the Age of 21 Gain Voting RightsIn 1928 women twenty-one or older finally received the right to vote in the UK. This did not come easy to women and took a lot to accomplish. The Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. “It was not until the Equal Franchise Act of 1928 that women over twenty-one were able to vote and women finally achieved the same voting rights as men. This act increased the number of women eligible to vote to fifteen million.” (Thevote). Some would later complain that the age should be lowered to eighteen, but this would not happen until 1967. The Representation of the People Act of 1918 helped pave the road to the Equal Franchise Act, it allowed women over the age of thirty who met a property qualifications to vote. Yet this left out a significant amount of women allowing only two-thirds of the total population of women in the UK to vote. It would unfortunately take another decade to reach the Equal Franchise Act allowing all women the right to vote with no restrictions except age. Many of the women who had fought for this right were now dead including Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Constance Lytton and Emmeline Pankhurst. However, the leader of the NUWSS during the campaign Millicent Fawcett, was still alive and attended Parliament to see the vote take place. Winston Churchill, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was opposed to women’s right to vote and argued that the country should not be put into the hands of a female majority. He was just one struggle women faced along with other hardships like being imprisoned, hunger strikes, and assault. Overall women are lucky to have the rights they do today and must never stop fighting to be just as equal as men. Video about 2 minutes: https://it-it.facebook.com/JeremyCorbynMP/videos/jeremy-corbyn-votes-for-women/10156562425118872/ Video about 3 minutes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1WxDvkO7Pw8 Citations: (john@spartacus-educational.com), J. (n.d.). Retrieved December 08, 2020, from https://spartacus-educational.com/W1928.htm Millicent Fawcett on the passing of the Equal Franchise Act - archive, 6 July 1928. (2018, July 06). Retrieved December 08, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/jul/06/millicent-fawcett-equal-franchise-women-vote-1928 Thevote. (n.d.). Retrieved December 08, 2020, from https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/overview/thevote/ Women's suffrage timeline. (2017, August 16). Retrieved December 08, 2020, from https://www.bl.uk/votes-for-women/articles/womens-suffrage-timeline |

Miranda Courtemanche |

| 1929 to 1933 | 1929 The Great Depression BeginsThe Great Depression was exactly how it sounds, a prolonged period of severe unemployment and struggles for people across the globe. It first began with a huge stock market crash of which Mary Klien describes in her article “The Stock Market Crash of 1929: A Review Article''; “Unlike most market disasters, the Great Crash was not the event of one day but a series of events stretched initially across the week from Wednesday, October 23, through Thursday, October 31. During these eight frantic sessions, a total of nearly 70.8 million shares were traded-more than had changed hands in any month prior to March 1928” (Klein). These events were sparked by the financial burden of the World War, but also the mass rumors that the U.S stock market was going to fail. After those rumors circulated people quickly started to lose faith in the institutions ability to keep their money safe. This one week changed the course of human history because of the drastic changes it enacted on the economy, but also how it affected the general morale. Sadness and misery were so widespread during this time that families were lucky if all of their children survived the century. Most families starved and were lucky if they even had a home. People lived in tents and couldn’t find jobs no matter where they travelled. Justice Brandeis once said, "The people of the United States are now confronted with an emergency more serious than war. Misery is widespread, in a time, not of scarcity, but of overabundance. The long-continued depression has brought unprecedented unemployment, a catastrophic fall in commodity prices and a volume of economic losses which threatens our financial institution”(Gay). This event was more serious than war because even in times of war people have hope that it will end. After the Depression, everyone lost hope and they lost what it meant to help others. This is one time period where people did not help other people as they should have. No one believed the dark time would end, until World War II began and suddenly people had something to fight for again. |

Sidney Wolford |

| Autumn 1929 | The Great Depression Begins - 1929The Great Depression is regarded as the most traumatic financial crisis the United States of America (USA) has ever faced. While it is commonly thought to have only affected the USA, it actually had drastic effects on European nations, too. The Great Depression is formally regarded to have started in the fall of 1929, but the financial situations that caused the depression to occur started before that. The Great Depression was caused by “dislocated and dysfunctional financial markets, low interest rates, instability of the crisis epicenter, investors’ panic, and high bankruptcy rates,” which took years to develop (Nenovski and Pamukova 31). The situation became particularly dire in August of 1929 when the USA entered a recession; however, the recession was seen as a typical, natural recession that properly reflected the ebb and flow of the economy. Ultimately, the cause of the recession—which was experienced globally and eventually developed into the Great Depression—was the manufacturing revolution; the Industrial Revolution prior to 1929 created what economists refer to as “a classic debt-deflation cycle” (Bruner and Miller 51). Unfortunately, the federal government in the USA did not react to this recession correctly. Instead, they “increased the discount rate from 5% to 6%, a level not seen since the contraction in 1921,” to lessen the ongoing speculation about USA stock exchanges (Bruner and Miller 50). This was then mimicked by other countries striving to stabilize their economies, which caused the global Great Depression. Arguably, however, what turned the recession into a full-blown depression was not even economics; fear may have been the underlying reason that the recession turned into a depression. More specifically, an unstable currency regime, poor federal response, banks panicking, and labor hoarding turned the recession into the Great Depression (Bruner and Miller 52). Citizens, the government, and banks were all terrified of the prospects and stopped trusting the stock market. This lack of trust caused the economy to crumble until it was stabilized in the spring of 1933. Works Cited Bruner, Robert F., and Scott C. Miller. “The Great Crash of 1929: A Look Back After 90 Years.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, vol. 31, no. 4, Fall 2019, pp. 43–58. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1111/jacf.12374. Nenovski, Tome, and Nela Pamukova. “Roots, Causes, Effects, and Lessons Learned from the Global Financial Crisis.” Journal of Sustainable Development, vol. 9, no. 22, June 2019, pp. 18–33. EBSCOhost https://proxy.library.kent.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=tr ue&db=bth&AN=138553815&site=ehost-live Further Information: Photo to Capture the Time and Short Video to Explain Why It Started Bourke-White, Margaret. “World’s Highest Standard of Living.” The Guardian, 18 Sep. 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/sep/18/great-depression-photography- art-exhibition-chicago. “The Great Depression Explained in One Minute.” YouTube, uploaded by One Minute Economics, 18 April 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sv7IP2qL0gg. |

Maria Ferrato |

| 30 Jan 1933 to 31 Dec 1933 | Hitler's Rise to Power (1933)“There is still no single acceptable or convincing explanation of the rise of Nazism to preponderant power in Germany and Europe” (Conway 399). During late January of 1933, a man of great hatred and ambition came to power after appointing himself chancellor of Germany, thus delivering a swift blow to democracy and the Weimar Republic. It was with the power of many he was able to achieve this feat, as he not only worked hard to maintain a proper and professional appearance, even using his own personal photographer and his biographer to make him look like a strong social and political figure (Hett 41). Hitler wasted no time when it came to achieving his goals of human “purification”, as within the first year of being chancellor, political rights were stripped from the Jewish people and gave them minimal power to fight against their ultimate oppressor. The only thing they were able to do was to fight domestically against discrimination (Weiss 216). Many Jews of Poland would boycott German products in order to make an impact, which dropped immeasurable value to German products overall (Weiss 219). Another big part of Hitler’s rise to power was his use of cinema propaganda (something he actually has in common with Stalin) in order to try and relay his message on an international scale. Hitler himself wrote that using the cinema industry in order to spread his power was even more impactful than any written propaganda could ever do (Ross). Hitler used both the cinema and written propaganda in order to spread the word about his ideas, which increased even more so as the year went on and World War II began. Conway, John S. "‘Machtergreifung’or ‘Due Process of History’: The Historiography of Hitler's Rise to Power." The Historical Journal 8.3 (1965): 399-413. Hett, Benjamin Carter. The Death of Democracy: Hitler's Rise to Power and the Downfall of the Weimar Republic. Henry Holt and Company, 2018. Weiss, Yfaat. "Polish and German Jews Between Hitler's Rise to Power and the Outbreak of the Second World War." The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 44.1 (1999): 205-223. |

Megan Geyer |

| 1 Sep 1939 to 2 Sep 1945 | World War II (1939-45)During my research on World War 2 for this project, I learned many facts I didn’t know about the war and even furthered my knowledge on some subjects I already knew. World War 2 was mostly a result of unresolved conflicts from World War 1 or the Great War and took place from September 1, 1939, to September 2, 1945. In World War 2 “the principal belligerents were the Axis powers- Germany, Italy, and Japan- and the Allies- France, Great Britain, the United States, the Soviet Union, and, to a lesser extent China,” however, many other countries were involved including Australia, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, and Guatemala (Royde-Smith 2020). Because of the many deaths said to have occurred during the war, many historians claim it is “the bloodiest conflict, as well as the largest war, in history” (Royde-Smith 2020). The war started on September 1, 1939, when “Hitler invaded Poland from the west: two days later, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany, beginning World War II” (History.com Editors 2020). The war of the Allied forces against Germany ended in February of 1945 with Germany’s surrender but the war would not fully end until September 1945. At the Potsdam Conference, which took place from July- August 1945, “U.S. president Harry S. Truman (who had taken office after Roosevelt’s death in April), Churchill and Stalin discussed the ongoing war with Japan as well as the peace settlement with Germany” (History.com Editors 2020). The war officially came to an end on “September 2, [when] U.S. General Douglas MacArthur accepted Japan’s formal surrender aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay (History.com Editors 2020). Sources: Britannica: World War 2: https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-II History.com – World War 2 https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/world-war-ii-history Here is a video I found to quickly summarize World War 2. World War II: Crash Course World History #38-https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q78COTwT7nE |

Kassandra Guzman |

| 18 Jul 1947 to 15 Aug 1947 | The 1947 Indian Independence ActThe 1947 India Independence Act was an act that the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed to free British India into becoming India and Pakistan. Both India and Pakistan (now modern-day Pakistan and Bangladesh) came into being on August 15th, a little less than a month after the act was passed on July 18th. The line between the two countries was based in religion, with a majority of Muslim people in Pakistan and a Hindu majority in India. Over 18 million people migrated to join the people within their religion and at least one million died from violence on the journey. This was the biggest mass migration in history. There are many historians that debate the reasoning for so much violence and bloodshed after gaining independence. Many argue that it had to do with the slow movement leading up to the act and the fact that tensions between Britain and India only worsened as World War II raged. Many say that the cause was the campaign of civil disobedience and protests, along with the differences between Gandhi, who spoke for much of India, and Jinnah, who spoke for much of Pakistan. It was the promise of the British to leave India in July of 1948, which was then moved forward to August of 1947, which is said to have led to the chaos in the newly formed countries. There was no sufficient plans for the British to partition India when they left the country, and this led to unrest and religious confrontation as the only form of rule they had known had left them. Many issues still plague India and Pakistan to this day, such as the region of Kashmir and who it belongs to. The National Archives. “The Road to Partition 1939-1947.” The National Archives, 3 Sept. 2019, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/the-road-to-partition/. |

Rebecca Drotar |