The industrial revolution marked a significant shift in the means of production, leading to what Karl Marx termed the “commodity” and the concept of “commodity fetishism.” In his analysis, Marx delves into the nature of commodities, how they disconnect people from their own labor, and how they can ensnare individuals in what he labels the “fetishism of commodities.” He also explores how this system affects the working day and deteriorates essential human functions.

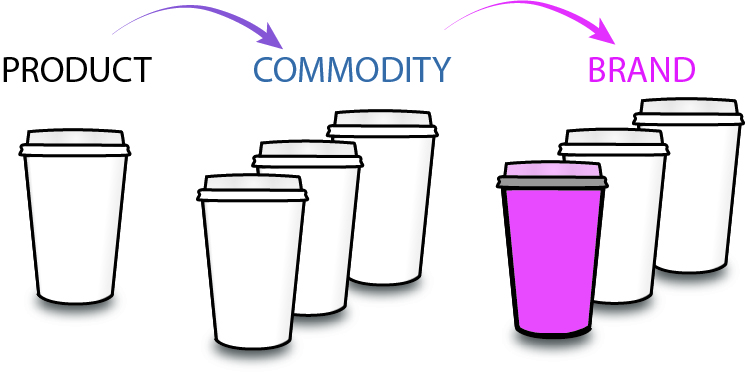

Marx doesn’t categorize all outcomes of human labor as commodities. He argues that it’s inherently human to adapt nature’s offerings for personal benefit. If someone, for instance, sews a jacket for personal use, it isn’t considered a commodity but rather a product with “use value” for the creator. It transforms into a commodity when it meets two crucial conditions set by Marx: it must satisfy a specific social need, and it must enter the complex capitalist market network to acquire an “exchange value.”

According to Marx, capitalism complicates the production process to maintain a social structure that empowers capitalists. He holds capitalism responsible for alienating laborers from their fellow workers and the products they create. In earlier times, individuals crafted their own items and saw the entire production process from start to finish, taking pride in their completed product. However, in the capitalist system, factory workers often focus on a single monotonous part of producing a commodity and may never witness the finished product or use it themselves.

To further simplify Marx’s idea, consider writing: in its simplest form on a page, one plus one equals two, and both the front-end and back-end processes are transparent and easily comprehensible. Yet, when this process becomes mechanized, the front-end results may be quicker, but the intricate back-end process involving zeroes, ones, and signals becomes invisible and requires specialists to understand. Marx argues that this complexity enables the bourgeoisie to exploit and commodify the proletariat. If consumers remain unaware of the harsh conditions and cruelty endured by children, women, animals, etc., in the production of certain goods, they may willingly purchase those products, even if they belong to the same class as the laborers who produced them.

Marx famously stated that “therefore, the relations connecting the labour of one individual with that of the rest appear . . . as what they really are, material relations between persons and social relations between things” (Parker, Critical Theory 382). This phenomenon fosters what Marx refers to as “commodity fetishism.” The shroud of secrecy surrounding the production process imparts a “mystical character” (Parker, Critical Theory 381) to commodities. For example, phones are designed for making calls, sending messages, and taking selfies, yet consumers often prioritize owning the latest version, despite its negative social and environmental impacts. Even if their current phones fulfill all the expected functions, this desire for the newest version exemplifies their “commodity fetishism.”

In essence, Marx’s analysis highlights how capitalism, with its complex production processes and alienation of laborers, can lead to a societal obsession with commodities, often at the expense of social and environmental well-being.

Further Reading Suggestions:

Parker, Robert. Critical Theory: A Reader for Literary and Cultural Studies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Parker, Robert. How to interpret literature: critical theory for literary and cultural studies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Mahmoud, Mustafa. Why I Rejected Marxism. Dār al-Ma’ārif, 1976.