The purpose of our collaborative chronology is to help orient you in the Victorian period and to offer some ideas for further research as you work on Paper 1 and Paper 2. I hope you enjoy browsing your classmates' work!

Timeline

Table of Events

| Date | Event | Created by |

|---|---|---|

| circa. 1806 to circa. 1873 | John Stuart MillIn 1806, John Stuart Mill was born in Pentonville, United Kingdom. At the age of 3, Mill began studying Greek and at age 8, he began studying Latin. By age 12, Mill had mastered algebra and had read novels from many Scottish and English historians. In his early teenage years, he studied political economy and calculus. Along with this tough course load, John was required to teach his younger siblings. These lessons were conducted by his father, James Mill. James Mill was a Scotsman who had been educated at Edinburgh University. He was a rigorous man who believed in ensuring John was as educated as he could be, that way he could become a successful man. This rigorous school schedule, eventually began to take a toll on Mill. At age 20, he suffered a mental crisis. During his rough time, Mill discovered the Romantics’ poetry and fell in love with it - especially “Wordsworth - though his new interests quickly led him to the work of Coleridge, Carlyle, and Goethe” (Stanford). Mill’s love for poetry led him to great literary success and was (one of) the reasons he met Harriet Taylor and fell in love. Sources https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/mill/ Suggested Readings

|

Jami Breon |

| 6 Mar 1806 | Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was born on 6 March 1806. Browning was the first of her family in two centuries to be born in England as her ancestors were Creole and lived in Jamaica where they owned sugar plantations that were known for using forced slave labor (Poets.Org). Browning was the oldest of twelve children which may be part of why she felt compelled to write about child labor conditions in England. She once said about her childhood, “Books and dreams were what I lived in and domestic life only seemed to buzz gently around, like bees about the grass,” (Poetry Foundation). Barrett Browning found herself living in a world of creativity and freedom. Unlike her siblings, she did not find the tediousness of “domestic life” to be satisfactory, instead, she found exploring the human condition to be a more valuable use of her time. Many of her pieces addressed social issues like: “the oppression of the Italians by the Austrians, the child labor mines and mills of England, and slavery, among other social injustices,”. (“Elizabeth”). Given her family background in owning slaves, her siblings being expected to work on the family plantation, and her residency in Italy, she was in the position to offer her first-hand experiences and opinions. Her passion for social change was admired by some, hated by others, but known by many. This included Elizabeth’s husband Robert Browning who first was an admirer of her work and world views but then became an admirer of Elizabeth herself. Elizabeth and Robert corresponded through letters for about two years before they eventually were married in 1846. As we discussed in class many people left the dreary U.K. for the warmth and culture of Italy, which was exactly what Elizabeth and Robert did once they were married. Interestingly Elizabeth’s skill and recognition outshone her husbands, and her work reached a wider audience. Specifically, Emily Dickinson had a portrait of Elizabeth in her bedroom and eventually after Wordsworth’s death she was a candidate for the title of “poet laureate”. |

Riley Dandurand |

| 1811 | Thomas Hood's Father DiesThomas Hood’s literary impact is integrated heavily with his humor which can be connected to his views on the education system, in the comics he produced, his ability to use puns in literature, and his fascination with the macabre. In 1811, when Thomas Hood was twelve years old his father passed away, this was the beginning of many deaths in his life. Death was a common occurrence in the Victorian period for Hood, however, it ignited the fires of humor that were present in his childhood and would shape his contributions to Victorian literature and art. In the active choice to use puns in his work, Hood showcased his deep concerns with class divisions, as puns were viewed as more primitive or rudimentary humor Thomas Hood championed the working class by including puns in his work as one could consider them a waste of labor as their worth is not obvious. The upper-class elite read Hood’s work; thus breaking down the linguistic class barriers and illustrating the necessity of the working class through the use of puns. Hood intertwined the dark nature of his humor, or ‘comédie noir’, with his critical views of Victorian culture and society. In doing so, Thomas Hood’s comics evoked morbid imagery that reflected both his individual experiences with death and that of the Victorian period. In one of his many poems, ‘The Song of the Shirt’ which criticized the treatment of female factory laborers, Hood takes the tone of Death and connects it to the impact of the repetitive labor in horrific conditions women faced. Grotesque and macabre imagery is apparent throughout Hood’s artwork and is a tool that he frequently used to overstate his distaste for the state of society at the hands of the British government.

Other Sources:

|

McKenna Wise |

| 8 Feb 1819 | John RuskinJohn Ruskin was born to a Scottish sherry merchant by the name of John James. Interestingly, he lived almost exactly as long as Queen Victoria, from 1819 to the year 1900. From childhood, his father supported an interest in the arts and encouraged his son to write poetry and paint, showing particular favoritism to the artist J.M.W. Turner, with whom Ruskin had a close relationship with for most of his life. His mother was very into gardening, which could have influenced his later preference for art to represent the natural world. Growing up religiously in the Catholic church also instilled in him a strong, faith-based world view. As a young man, he attended and graduated from Oxford, and shortly after published the first volume of Modern Painters. In totality, he would end up writing five separate volumes in this series over the course of seventeen years. In 1849, he married childhood friend Effie Gray. However, this marriage was infamously ended due to a failure to consummate, and Effie did in fact undergo an examination to prove her virginity before breaking the marriage off and instead to marry Ruskin’s close friend John Everett Millais. At the time, this was very scandalous. The attached image is a drawing by Millais titled “Married for Love” which is thought to be related to falling in love with Effie. After this annulment, Ruskin seems to have developed a highly questionable attraction to young girls. He met Rose La Touche when she was only ten, and proposed to her at eighteen--when he was considerably older than her. She died at 27 years old but Ruskin insisted that he was visited by her spiritual presence after her death. Nevertheless, Ruskin went on to continue writing for a large majority of his life, and eventually self-publishing. His very last work was an unfinished autobiography. Nearing the end of his life, he was onset with bouts of madness and what was probably serious mental illness. He was taken care of by his cousin Joan, who burned all of the letters between Ruskin and Rose shortly after his death, as well as any memorials he kept of her, which may have been performed by his own instruction. Image Information: CREATOR: John Everett Millais TITLE: Married for love WORK TYPE: drawing DATE: 1853 Additional Readings: Alexandra Mullen. “John Ruskin: A Brave, Unhappy Life.” The Hudson Review, vol. 53, no. 3, 2000, pp. 407–19. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3853022. Accessed 15 Sept. 2023. Dearden, James S. “The Portraits of Rose La Touche.” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 120, no. 899, 1978, pp. 92–96. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/879105. Accessed 15 Sept. 2023.

|

Sarah Troub |

| 24 Dec 1822 to 15 Apr 1888 | Matthew ArnoldMany readers have seen Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) as the most modern of the Victorians. Arnold defines "the modern" in his first lecture as a professor of poetry at Oxford, "On the Modern Element in Literature." This lecture marked Arnold's transition from poet to social and literary critic. He argued that the great need of a modern age is an "intellectual deliverance.": preoccupation with the arts of peace, the growth of a tolerant spirit, the capacity for refined pursuits, the formation of taste, and above all, the intellectual maturity to "observe facts with a critical spirit" and "to judge by the rule of reason." The views Arnold developed in his prose works on social, educational, and religious issues have been absorbed into the general consciousness, even if they are as far as ever from being realized. While he harshly satirized the hypocrisy of his era, he believed that the possibility of a better society for all depended on critique and a vision of human perfection. That vision is explicitly expressed in the late essay "A French Critic on Milton." In his article, Arnold argues that human progress consists of a continual increase in the number of those who, ceasing to live by the animal life alone and to feel the pleasures of sense only, come to participate in the intellectual life and find enjoyment in the things of the mind. Further Reading Suggestions: Arnold, Matthew. Culture & anarchy. e-artnow, 2018. |

Fereshteh Majdi |

| circa. 1830 | The Imperial Gothic, a new form of fiction in the 18th centuryThe word Gothic is defined by the Britannica Dictionary as: of or relating to a style of writing that describes strange or frightening events that take place in mysterious places. Or, of or relating to a style of architecture that was popular in Europe between the 12th and 16th centuries and that uses pointed arches, thin and tall walls, and large windows. Gothic Fiction is often believed to have come to fruition when in 1764, Horace Walpole first used the word ‘Gothic” when he titled his novel, The Castle of Otranto, with the subtitle reading, A Gothic Story. Perhaps Walpole used the term gothic to describe the castle within the novel, but he pretended that the story was an antique, with providing a preface in which the original story was published in Italy in 1529. The story itself is not truly from 1529, but perhaps that was a joke in on itself. (The British Library) Gothic fiction is defined by Britannica as a European romantic pseudomedieval fiction having an atmosphere of mystery, terror, and even the supernatural. Some of the most popular authors to derive within this literature category is often known as the ones who arguably popularized it within classical horror, such as Mary Shelley, Bram Stoker. Their horror stories such as Frankenstein, (1818) and Dracula (1897). Both in which introduced the existential type of nature of humankind that makes up the mystery and terror within. (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica) The term, ‘imperial Gothic’ refers to the late 19th century fiction set within the British Empire. Within imperial Gothic fiction, it employs or adapts elements drawn from gothic novels. This could be elements such as gloomy, forbidding atmosphere or weather, brutal or tyrannical men, violence or punishment, the presence of the supernatural or occult. (The British Library) The term “imperial Gothic” is first explored by Patrick Brantlinger in his Rule of Darkness: British Literature and Imperialism, 1830–1914, published in 1988.To make it simpler to define what Imperial Gothic is, Patrick Brantlinger states it as thus, “Imperial Gothic expresses anxieties about the waning of religious orthodoxy, but even more clearly it expresses anxieties about the ease with which civilization can revert to barbarism or savagery and thus about the weakening of Britain's imperial hegemony.” Brantlinger also says there are three principal themes of imperial Gothic: an individual regression or “going native,” an invasion of civilization by the forces of barbarism or demonism, and the opportunities for adventure/heroism in the modern world. Brantlinger (Imperial Gothic, 1) Perhaps, we can see this in works such as Jackle and Hyde by Robert Stevenson, where a man can have a ‘second’ nature that can be something barbaric or deeper and darker version of himself despite being a respected Victorian man. In Dracula, by Bram Stoker, a vampire seeks to invade the shores of England from his country that surrounds the outskirts of the Victorian Empire, spreading his disease like undead vampirism. In Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley, where in a time where science and knowledge are deemed the innovation of the time within England, becomes the tragic consequence to an uncontrollable horror. Imperial Gothic is essential all gothic literature or gothic novels that contain the deeper fear and/or issues that prevailed within the 18th century British Imperial Empire. Sources/Further readings:

|

Tristan Drye |

| 15 Sep 1830 | Opening of Liverpool & Manchester Railway

Articles

|

David Rettenmaier |

| 5 Dec 1830 to 29 Dec 1894 | The Life and Times of Christina RossettiChristina Rossetti was born in London in 1830, the youngest of four children born to Gabriel Rossetti and Frances Polidori. Both of her parents were highly educated and raised Rossetti and her siblings with an appreciation for art and education. Rossetti’s mother raised her and her sister at home to be governesses, while her brothers were sent to boarding school. In her fifteenth year, Rossetti became seriously ill, although there are speculations on whether her illness was primarily mental or physical. Nevertheless, she suffered from depression and various periods of illness her entire life.

As a child, Rossetti and her two brothers, William and Dante Gabriel, would often play games that involved composing sonnets. In 1848, Rossetti first poems were published, “Death’s Chill Between” and “Heart’s Chill Between,” in The Athenaeum, a British literary magazine; although she published under a pseudonym. It wasn’t until 1862, when Rossetti published Goblin Market and Other Poems, that she would print under her own name.

In the late 1840s as well, Rossetti’s brothers would become founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of artists opposed to the Royal Academy and who focused on Romanticism, sincerity and nature within their art. While Rossetti was associated with the society (she would publish some of her early poems in the Pre-Raphaelite magazine, The Germ, as well as occasionally act as an art model), she was never an official member.

Throughout her life, Rossetti had several suitors, including Pre-Raphaelite member James Collinson and painter John Brett, who is the suspected inspiration behind Rossetti’s poem “No, Thank you, John.” Rossetti never married and by the late 1870s was very self-conscious of her looks, which had been affected her Graves’ disease. Over this period, she suffered from several different ailments which, along with her temperament, made her unlikely to leave the house. This melancholy reflected in much of her poetry, which often reflected themes of sadness and death.

Near the end of her life, Rossetti wrote much less and what she did write mainly reflected her religious faith and much of it was donated to Christian charities. Rossetti died near the end of 1894 after two years with cancer. After her death, her brother William edited and published many of the poetry she had written later in life or deemed unworthy of publication prior in a collection entitled New Poems, Hitherto Unpublished or Uncollected.

Further Reading Barringer, Tim. “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 1 Sept. 2017, https://doi-org.er.lib.k-state.edu/10.1093/ref:odnb/64454.‌ “Christina Rossetti.” Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/christina-rossetti. “Christina Rossetti.” The British Library, www.bl.uk/people/christina-rossetti. Duguid, Lindsay. “Rossetti, Christina Georgina.” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sept. 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/24139. |

Destiny Munns |

| Jun 1832 | Reform Act

ArticlesCarolyn Vellenga Berman, “On the Reform Act of 1832″ Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 29 Aug 1833 | Slavery Abolition Act

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 29 Aug 1833 | Factory Act

ArticlesRelated Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| Winter 1833 | The Factory Act of 1833Browning was inspired by the publication of the Report of the Children’s Employment Commission by Great Britain Commissioners for Inquiring into the Employment and Condition of Children in Mines and Manufactories, which highlighted the horrendous working conditions for children during this time. Many children worked in life-threatening conditions underground in the mines, or they were responsible for collecting parts that fell under machines. As a result, the amount of work-related child fatalities skyrocketed. Additionally, Industrialization moved families from agricultural work to work like coal mining and manufacturing jobs. Children were expected to help with familial income which meant 14-hour workdays accompanied by less pay than their adult coworkers who may or may not be doing the same job as the children. (“Report”). Many businesses were interested in hiring young children who would take any job and any amount of pay because they were cheaper labor than adults. Further, the study found that “children as young as five spent twelve-hour days sitting in small tunnels deep in the dark underground, waiting to open or close ventilation doors… One seventeen-year-old boy interviewed for the Report said, ‘I never see daylight now, except for Sundays,’” (Getz). The Factory Act of 1833 attempted to protect children under the age of nine from being employed, as well as, limit the amount of hours that children were able to work in a week (Nardinelli). This was a feeble attempt at protecting children from exploitation; furthermore, these laws proved to be ineffective as there were still children under the age of nine being employed and working in deplorable conditions. Browning’s piece could be considered what is called “Protest Literature” which brings light to social injustices to invoke change. Oftentimes times protest literature appeals to the readers’ emotions by giving descriptive instances of the brutal labor conditions, conditions of asylums, etc.

Further Readings: Council, Birmingham City. “Life for Children in Victorian Britain.” Life for Children in Victorian Britain | Birmingham City Council, Birmingham City Council, 12 Feb. 2018, www.birmingham.gov.uk/info/50139/explore_and_discover/1609/life_for_chi…; “Elizabeth Barrett Browning.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 2 Aug. 2023, www.britannica.com/biography/Elizabeth-Barrett-Browning. “Elizabeth Barrett Browning.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/elizabeth-barrett-browning. Accessed 1 Sept. 2023. |

Riley Dandurand |

| 2 Feb 1835 | Minute on Indian Education

On February 2nd, 1835, Thomas Macaulay, a British politician and historian, delivered a speech entitled “Minute on Indian Education.” In this speech, he described his discussions with other scholars on the topic of Indian education. The chief question was if instruction in schools should occur in the native Arabic or Sanskrit, or the foreign English. Macaulay disagrees with many arguments cast forth - including those regarding the history of India, the fact that Indian religious texts were written in Sanskrit, and the comparatively poor sales of Sanskrit books. This speech, and his later work in India, would become the foundation of Western institutional education in India.

His Minute on Indian Education contended that, “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia”. This imperialist philosophy that Macaulay held is strongly shown in both his writings and his life's work. The approach to education that he advocated for sought to create "a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect". His ideas came to fruition in the same year, when the Council of India passed the English Education Act of 1835, which enforced the teaching of Western curriculum in English. Macaulay, Thomas B. Minute on Indian Education. 1835. COVE, https://studio.covecollective.org/anthologies/english-630-victorian-lite....

Further reading:

|

Drew Bellamy |

| 20 Jun 1837 | Victoria becomes queenVictoria (1819-1901) becomes queen after the death of her uncle, William IV (1765-1837).

Coronation portrait by George Haytor (1837) |

Anne Longmuir |

| 14 Jun 1839 | First Chartist Petition

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 4 Aug 1839 to 30 Jul 1894 | Life of Walter PaterWalter Horatio Pater was born on August 4th, 1839, in London. When he was two years old, his father died. At fourteen, his mother died, leaving Pater and his three sisters with an aunt. Having grown up knowing death well, he was interested in religion and at one point considered taking up orders to join the church clergy. Much of his early poems were related to Christianity, but Pater went through a difficult period and split from the church upon entering university. He turned to classical studies and was tutored by those who rejected religion for cultural studies. At this point, the family was not doing well economically, and his sisters moved to Germany to live cheaper with an aunt’s care. (Brake) Pater tutored and lectured about classics and philosophy at Brasenose College at Oxford. He attracted controversy as he often worked with homoerotic motifs. His first book, Studies in the History of the Renaissance, is a collection of essays, many of which were articles originally written for the Fortnightly Review. Having angered the religious aspects of the education system, he was told by the university to not seek another university post. He also censored himself in order to not get himself into legal trouble. His reputation, now linked with aestheticism, which, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, means, “the pursuit of, or devotion to, what is beautiful or attractive to the senses, esp. as opposed to an ethically or rationally based outlook,” earned him followers like Oscar Wilde and George Moore among others. Pater died on July 30, 1894, in Oxford. Pater’s notable works include The Renaissance (1873), his only finished novel, Marius the Epicurean (1885), Imaginary Portraits (1887) which are shorter pieces of philosophical fiction, and Appreciations (1889), critical essays on English subjects. Greek Studies (1895), Miscellaneous Studies (1895), Essays from the Guardian (1896, 1901), and the unfinished romance Gaston de Latour (1896) were published after Pater’s death. Works Cited: “aestheticism, n.”. Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford university Press, July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/6703520666. Brake, Laurel. “Pater, Walter Horatio (1839-1894), author and aesthete.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, May 25, 2006. Oxford University Press, https://www-oxforddnb-com.er.lib-k-state.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-978019814128-e-21525. Further Reading: Barolsky, Paul. “Walter Pater and the Aesthetics of Abstraction.” Notes in the History of Art, vol. 29, no. 4, 2010, pp. 43-45. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23208978. Brake, Laurel. “Pater, Walter Horatio (1839-1894), author and aesthete.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, May 25, 2006. Oxford University Press. Accessed 15 September 2023, https://www-oxforddnb-com.er.lib-k-state.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-978019814128-e-21525. "Walter Pater." Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 18 Dec. 2017. academic-eb-com.er.lib.k-state.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Walter-Pater/58708. |

Kayla Burns |

| 17 Aug 1839 | Act on Custody of Infants

Related ArticlesRachel Ablow, “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act” Kelly Hager, “Chipping Away at Coverture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857″ Jill Rappoport, “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1842 | Tennyson: An Arthurian FanboyThe Parting of Lancelot and Guinevere (from Illustrations to Tennyson's "Idylls of the King") 1874 Lord Alfred Tennyson’s poem The Lady of Shalott about a woman who weaves day in and day out in a tower above a town called Camelot and can only look at the world through a mirror and shadows. In this fairy-tale scenario, The Lady of Shalott would be cursed if she stopped weaving and looked to the village below. Within the first five lines, Camelot is mentioned as the name for the city that the Lady resides near- whether it is the Legendary Camelot or a city by the same name it is unclear- and Lancelot appears later in the poem- a second clear Arthurian reference in the same poem suggests Tennyson was indeed referring to the original Legendary Camelot- who ends up as the demise of the Lady of Shalott, fulfilling her curse. Arthurian legend strongly influenced the Victorian Era culture. From fashion, travel, art and literature, Victorian society was enamored with Arthurian themes of grand Camelot, dashing Lancelot, brave Arthur, and the honor of the knights. So, unsurprisingly, The Lady of Shalott as well as several other works by Tennyson are based on Arthurian legend. Tennyson was said to be one of the figureheads for the Arthurian revival in the late 1800s and as a result of his fascination, some speculators say that Tennyson was a large reason that a wave of art and other forms of popular media fascinated with Arthurian themes appeared as inspiration from his work. However, other critics like Roger Simpson say that “Tennyson was not so much the father of the nineteenth-century Arthurian renaissance as he was a major figure who was a part of- and profited from- the prevailing contemporary fascination with the stories of Camelot” (Simpson). Whichever speculation is true, Tennyson’s fascination gave us some wonderful poetry that inspires and entertains readers to this day.

If the subject of the Arthurian revival in the Victorian Era is an interest to you, I suggest these readings! Camelot Regained: the Arthurian Revival and Tennyson, 1800-1849 by Roger Simpson (https://k-state.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01KSU_INST/1177os2/alma993640843402401 ) The Arthurian Revival in Victorian Art by Debra Mancoff (https://k-state.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01KSU_INST/1177os2/alma993832423402401 ) Arthuriana by Alan Lupack: https://muse-jhu-edu.er.lib.k-state.edu/article/430563 |

Kaia Hayes |

| 1842 | The Victorian Woman: The Lady of ShalottExpected to stay indoors, upkeep domestic tasks, raise the children, keep a home, and often not allowed to participate in society, The Lady of Shalott shows an example of the rigid expectations placed upon Victorian Women. The title “The Victorian Woman” came to represent this type of personage in literature and is even used today. The moment that the Lady of Shalott stops conforming to the rules placed upon her, she is met with her tragic end. The Lady of Shalott is an extreme scenario of the consequences that the Victorian woman would face if she were to step outside of the rigid box placed upon their shoulders: death. For the real Victorian Women, a type of social death may have been more likely, where if these strict expectations were not upheld, they would be looked down upon, outcasted, and personal or physical repercussions from her family. Another aspect of the Victorian Woman that is not overtly mentioned in The Lady of Shalott is the idea of a woman’s sexuality. Women were expected to remain chaste, “pure”, and loyal to their husbands, and if they were not, they were seen as “fallen” or ruined. Yet it was common for men to have many sexual partners throughout their life, even during their marriage, and unfortunately, divorce was not an option for women at this time. There was no escaping these rules: women could not own property if married for most of this time period, they could not vote, and they had no independence outside o their families. The social stereotypes were upkept in this time through literature: it was a common theme to see unchaste women such as adulteresses meet tragic ends in novels or poems. Fear, embarrassment, and shock controlled the society and rigidly upheld these standards, of which we still see lasting effects of in the twenty-first century.

If the subject of the Victorian Woman interests you, here are some readings I suggest! The Victorian Woman Question in Contemporary Feminist Fiction by J King (https://k-state.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01KSU_INST/1260r8r/cdi_askewsholts_vlebooks_9780230503571 ) From Spinster to Career Woman: Middle-Class Women and Work in Victorian England by Arlele Young (review) https://k-state.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01KSU_INST/1260r8r/cdi_crossref_primary_10_2979_victorianstudies_63_3_12 Women Writing the Neo-Victorian Novel: Erotic "Victorians" by Kathleen Renk; 2020 https://k-state.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01KSU_INST/1260r8r/cdi_askewsholts_vlebooks_9783030482879 |

Kaia Hayes |

| 2 May 1842 | Second Chartist Petition

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1844 | The Struggle to Survive WhitechapelA hard to miss facet of the Victorian era were the slums or working districts of cities brought on and formed in part by the industrial revolution. Frederich Engels in his appeal against industrialization The Condition of the Working Class in England 1844 specifically brings to the forefront one of the most notorious slums in London, Whitechapel. Maybe most notable for its local serial killer Jack the Ripper, Whitechapel was home to approximately 900,000 people. Strawberry tours, a praiseworthy walking touring company in London boasts, “Whitechapel was the worst district in London’s East End, and was considered a “no-go-zone” for those living in London’s other boroughs… And this was all before Jack the Ripper came along” (What Was Life Like in Whitechapel). The poverty and destitution of this area were so great as to attract philanthropists from around the world. Many would spend a few days in the area to immerse themselves in the poor man’s experience. Morbid and sad attractions such as Whitechapel are where the phrase “slumming it” comes from. Even with wealthy donors and missions galore this district never ceased to be in need of such charities. Not only were most of the inhabitants immigrants and a vast number also homeless, but the poor families with homes were overrun and crowded. Sometimes as many as three families would be confined to sharing one room. The streets however were not much more desirable as they were a dumping ground for sewage and a breeding ground for disease. Mortality rates reached up to 50% in children under the age of five. Because of a dire need for money prostitution was a profession run rampant as well. Slums such as this served as Engel’s battleground for waging war against industrialization through describing his gut wrenching experiences with them. Image: Gustave Dore. Wentworth St, Whitechapel. Wellcome Collection, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.24718829. Accessed 7 Sept. 2023. Additional Articles: Koven, Seth. Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics In Victorian London. E-book, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2006. Slum Tourism : Poverty, Power and Ethics, edited by Fabian Frenzel, et al., Taylor & Francis Group, 2012. Geary, Rick. Jack the Ripper : A Journal of the Whitechapel Murders 1888-1889. NBM ComicsLit, 1995. Mentor Text: ENGELS, FREDERICK. Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844. DOUBLE 9 BOOKS, 2023. |

Robyn Logan |

| 1845 to 1852 | The Irish Potato Famine 1845-1852The Britannica Dictionary defines the word famine by: a situation in which many people do not have enough food to eat. While Spanish Conquistadors brought the potato plant to Europe in 1536, it was Sir Walter Raleigh who introduced potatoes to Ireland in 1589. (“Potato Facts | Fun Facts about Potatoes”) The potato plant was a hardy, calorie-dense plant that would easily grow within the Irish soil. Before the Famine, nearly half of Ireland’s 1840s rurally poor population almost exclusively relied on potatoes for their diet. While the people of Ireland relied on the one or two common types of potato crops, a strain of water mold arrived from North America and destroyed potato crops at an extreme rate. Mokyr (“Great Famine | History, Causes, and Facts”) The type of blight that affected the crop destroys both the edible roots or tubers, and leaves of the potato plant. The type of water mold that was such wide spread is known as Phytophthora Infestans. The potato blight that caused the Famine was first noticed in County Cork in September of 1845, however, the full extent of the outbreak was not known until the general harvest that October. Mokyr (“Great Famine | History, Causes, and Facts”) The British Government did try to give relieve to the famine, but it was not enough or inadequate. Prime Minister Asir Robert Peel allowed the export of grain from Ireland to Great Britain, as well as import corn from the United States to avert the starvation. However, Peel’s policy regarding the export of grain from Ireland was more of a laisses-fair approach to the plight. Any financial aid to the starving Irish poorer population was to be held by the landowners. Since the peasantry was unable to pay the rent to the landlords, the landlords in turn ran out of funds to provide aid. And thus, much of the Irish tenant farmers or laborers were forced off the lands they worked on. Mokyr (“Great Famine | History, Causes, and Facts”) To b3e able to move forward with escaping the famine and to survive, those that were able to immigrated out of Ireland out of the hopes to find a better life. According to The National Archives, up to two million Irish immigrants sailed to North America during the Famine, with an estimated 5,000 ships were used to sail the two-month voyage. Through assessments on the populace that died during the Famine, of either disease or hunger still stands around one million. The mass deaths and immigration drastically reduced the population of Ireland. (UK Parliament) Many people of note were born in Ireland during this time. One of which is Bram Stoker. (“Bram Stoker - Dracula, Books & Quotes”) Sources/Further reading:

|

Tristan Drye |

| 25 Jun 1846 | Repeal of Corn Laws

ArticlesAyse Çelikkol, "On the Repeal of the Corn Laws, 1846" Related ArticlesPeter Melville Logan, “On Culture: Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy, 1869″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| The start of the month Autumn 1847 | The Birth of Abraham Stoker November 8, 1847Abraham Stoker, or known as Bram Stoker, was born on November 8, 1847 in Dublin, in Ireland to his father Abraham Stoker Sir, and Charlotte Matilda Blake Thornley Stoker. Stoker was one of seven children, born during the height of the Irish Potato Famine. Bram also suffered from a range of illnesses that left him bedridden until the age of seven. (“Bram Stoker - Dracula, Books & Quotes”) From 1864-1870, Stoker attended Trinity College and earned a degree in mathematics. Stoker would then go on to work as a civil servant at Dublin Castle. This was when Stoker would work in his free time as an unpaid writer for the Dublin Evening Mail, a local newspaper. (Academic) Much of his early work for the paper was writing reviews for theatrical productions. This was also the time Stoker wrote his short stories, and published in 1872, "The Crystal Cup." (Academic) (“Bram Stoker - Dracula, Books & Quotes”) Stoker worked his civil service job for nearly 10 years, before meeting and building a relationship with Sir Henry Irving, whom Stoker met after reviewing a production of Hamlet, featuring Irving. (Academic) Stoker would go on to become Irving's manager, accompany him on his American tours as well as writing his correspondence. (“Bram Stoker - Dracula, Books & Quotes”) Stoker would remain Irving's manager and friend for over 27 years until his death in 1878. (Academic) Stoker would publish his first novel, The Primrose Path in 1875. He published Under the Sunset, a collection of short stories 1882, and his second novel followed in 1890, The Snake's Path. (Academic) Stoker wrote several other novels: The Mystery of the Sea (1902), The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903), and The Lady of the Shroud. (1909) (Academic) Now, Stoker published his magnum opus, Dracula in 1897. The book itself did garner critical success after its release. However, it did not achieve its known popularity until long after Stoker's death. (Academic) What makes Dracula so memorable, is how it is written. Dracula is made of diary and journal entries written by the main characters. The novel influenced vampire representation in Western pop culture throughout the 19th and 20th century. Dracula has been adapted for film, television, stage, and further book adaptations. (Academic) Sadly, after the death of Irving and the publishing of Dracula, Stoker spent his remaining years dealing with ill health and financial issues. (“Bram Stoker - Dracula, Books & Quotes”) Stoker died in London, on April 20th,1912. His death has often been disputed by historians. Various reports cited his cause of death as complications from exhaustion, complications of a stroke, or even syphilis. (Academic)

Sources/Further readings:

|

Tristan Drye |

| 1848 | Marx’s The Communist Manifesto and the Social Dynamics of the Industrial RevolutionSir Isaac Newton’s third law of motion, a fundamental principle of physics, can provide us with a profound insight into the dynamics of not just physical objects but also societal and economic systems. This law posits that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. This concept can be applied metaphorically to the societal shifts witnessed during the Victorian era, particularly in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution, a momentous and transformative force in history, can be seen as the “action” in this analogy. It was characterized by a rapid and unprecedented surge in technological advancements and industrialization, leading to the mass production of goods, urbanization, and a significant shift in labor patterns. As the factories churned out goods and new industries emerged, there was an accumulation of capital and means of production in the hands of a select few, creating a significant disparity between the classes. To illustrate this, consider the emergence of textile mills in Victorian England. These mills revolutionized the production of textiles, resulting in increased efficiency and output. However, the benefits of this industrialization were not equally distributed. Factory owners and capitalists gained enormous wealth and power, while the working class, or the proletariat, often endured deplorable working conditions, long hours, and meager wages. This growing gap between the affluent bourgeoisie and the struggling proletariat exemplified Newton’s third law in a societal context. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, influential philosophers and economists of the time, observed this stark divide and they postulated that, as a reaction to the entrenched inequality and exploitation, the working class would eventually unite and rise against the bourgeoisie, leading to a revolution. This theory, known as Marxism or communism, envisioned a society where the means of production would be collectively owned, eliminating the disparities of wealth and power. In essence, Newton’s third law of motion can serve as a lens through which we can analyze the societal repercussions of historical events like the Industrial Revolution. It reminds us that profound societal actions, such as this industrial transformation, inevitably generate reactions, often in the form of social movements, political ideologies, or revolutions, as people respond to the consequences of these changes in an effort to restore balance and justice. Further Reading Suggestions: https://ilostmyprayerhanky.com/2017/09/17/communist-manifesto-part-1/ https://ilostmyprayerhanky.com/2017/09/24/cm2-capitalists-workers/ https://ilostmyprayerhanky.com/2017/10/07/objections-communism-manifesto-3/ |

Maryam ElZayat |

| 1848 | Pre-Raphaelite BrotherhoodThe Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was an artistic society founded in 1848 that John Ruskin famously defended, made up of authors, poets and painters alike. He was highly-involved with the organization and his writing of Modern Painters, especially in the later volumes, both mention and influence their ideals. Their aim as a brotherhood was to impact the artistic scene of their time by returning to Renaissance Era (and Medieval) artistic tradition and visual representation. Hence why they were called “Pre-Raphael”. Subjects that they were drawn to in particular were Christian religious scenes and true-to-life landscapes, of which Ruskin was a particular fan. His stance on the brotherhood swung both in positive and negative directions over the course of the movement’s lifespan, and he did not always agree with the organization’s aims, but he was close with some of the founders. Portraiture of Ruskin created by founder of the brotherhood John Everett Millias is well-preserved and often used alongside photographs to portray Ruskin as he was in life. Visually, the group was concerned with representing the real world and biblical scenes with minute detail and realism. They were also advocates for making art because it was art, rather than for use as a political tool. Many of their works expressed concern about Victorian society and morality. Later, as the group lost traction and eventually dissolved, many of the members leaned into the Arts & Crafts movement that celebrated “decorative” arts, such as textiles and jewelry. You will note that in Modern Painters, Ruskin denounces decorative art and language, comparing it to the varnish or frame of a painting, rather than the content itself, but also states that “it is not by the mode of representing and saying, but by what is represented and said, that the respective greatness either of the painter or the writer is to be finally determined” which hints he was open to their ideas, despite the initial unpopularity of the old art styles that they revived, because of the intellectuality behind it. Some relevant members of this brotherhood included painter John Everett Millais, who painted the same Mariana that stars in Tennyson’s poem (and later married Ruskin’s ex-wife), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose sister wrote Goblin Market. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had members well-versed in writing, sculpture, poetry and other media in order to create and influence a large span of artistic forms with their ideologies. Image Information: CREATOR: Millais, John Everett, Sir, 1829-1896 TITLE: John Ruskin DATE: 1854 MEDIUM: oil MEASUREMENTS: 79x68cm Further Readings: Meagher, Jennifer. “The Pre-Raphaelites.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, 1 Jan. 1AD, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/praf/hd_praf.htm. Payne, Christiana. “John Constable, John Ruskin, and the Pre-Raphaelites.” The British Art Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, 2015, pp. 78–87. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24914016. Accessed 15 Sept. 2023. Roe, Dinah. “The Pre-Raphaelites.” British Library, 15 May 2014, www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-pre-raphaelites. |

Sarah Troub |

| 10 Apr 1848 | Chartist Rally, Kennington

Led by Feargus O’Connor, an estimated 25,000 Chartists meet on Kennington Common planning to march to Westminster to deliver a monster petition in favor of the six points of the People’s Charter. Police block bridges over the Thames containing the marchers south of the river, and the demonstration is broken up with some arrests and violence. However, the large scale revolt widely predicted and feared fails to materialize. ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1851 | The "Dover Beach""Dover Beach" is the most celebrated poem by Matthew Arnold (1822 – 1888), a writer and educator of the Victorian era. It was first published in 1867, though it is generally believed to have been written around Matthew Arnold's honeymoon in 1851. Among the prominent Victorian writers, Matthew Arnold is distinctive in that his reputation rests equally upon his poetry and criticism. While only a quarter of his productive life was given to writing poetry, many of the same values, attitudes, and feelings expressed in his poems achieve a more balanced formulation in his prose. This unity was obscured for most earlier readers by the usual evaluations of his poetry as ambiguous and often satirically witty in its self-imposed task of illuminating the social consciousness of England. "Dover Beach" is a stand-out poem in the Victorian canon and is often claimed to be the greatest poem of the era. The main reason is that it differs from the poetry of its day. Other Victorian poets like Alfred Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning wrote with strict formality. While Arnold's other poetry is similar to theirs, this poem stands out in its refusal to settle down into a reliable pattern, which is why it is a forerunner to literary movements of the 20th century. Further Reading Suggestions: Epstein, Joseph. "Matthew Arnold and the Resistance." Commentary 73.4 (1982): 53. Gottfried, Leon. Matthew Arnold and the Romantics. Routledge, 2016. Larracey, Caitlin. "Carlyle, Arnold, and Wilde: Art and the Departure from Humanism to Aestheticism in the Victorian Era." Undergraduate Review 8.1 (2012): 102-107 |

Fereshteh Majdi |

| 1 May 1851 to 15 Oct 1851 | Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was an event in the history of: exhibitions; world’s fairs; consumerism; imperialism; architecture; collections; things; glass and material culture in general; visual culture; attention and inattention; distraction. Its ostensible purposes, as stated by the organizing commission and various promoters, most notably Prince Albert, were chiefly to celebrate the industry and ingeniousness of various world cultures, primarily the British, and to inform and educate the public about the achievement, workmanship, science and industry that produced the numerous and multifarious objects and technologies on display. Designed by Joseph Paxton, the Crystal Palace (pictured above) was a structure of iron and glass conceptually derived from greenhouses and railway stations, but also resembling the shopping arcades of Paris and London. The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations became a model for World’s Fairs, by which invited nations showcased the best in manufacturing, design, and art, well into the twentieth century. ArticlesAudrey Jaffe, "On the Great Exhibition" Related ArticlesAviva Briefel, "On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition" Anne Helmreich, “On the Opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854″ Anne Clendinning, “On The British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25″ Barbara Leckie, “Prince Albert’s Exhibition Model Dwellings” Carol Senf, “‘The Fiddler of the Reels’: Hardy’s Reflection on the Past” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1852 | Florence NightingaleFlorence Nightingale was born in 1820 to a wealthy British family. Throughout her youth, her father oversaw her extensive education; she was taught language, philosophy, mathematics, history, and literature. Her interest in nursing manifested itself at a very young age as she would often help relatives and nearby villagers who had fallen ill. At sixteen years old, the religiously devout Florence felt herself divinely called toward the nursing profession. This vocation was strongly opposed by her family, for nursing in the mid-nineteenth century was a low-paying profession for middle-class laborers with little to no training. Her frustrated hopes and feelings of grief inspired her to write the semi-autobiographical essay “Cassandra” in 1852—though it was not published until 1928. This work was written as a criticism of the limitations placed on women of the English upper-class as Nightingale felt that the bounds of her own social position kept her from pursuing her dreams of nursing. She also explored the unequal opportunities available to Victorian men and women. During her period of professional frustration, Nightingale spent much of her time Europe and Asia. While in Germany, she was allowed to study in Kaiserswerth where she was taught nursing and hospital administration. After a short stint as the superintendent of a small hospital for gentlewomen, Nightingale left England to work as a military nurse in the Crimean War. Upon her arrival, she was distressed by the unsanitary hospital conditions. Nightingale insisted upon basic hygiene such as clean bandages, regular cleanings, and sufficient nutrition for the wounded soldiers. Following the war, the now respected nurse returned to England to open the Nightingale School of Nursing at St. Thomas’ Hospital which became a respected school for female study. Before her death in 1910, she was honored as the first female recipient of the British national award the Order of Merit. Additional Readings: McDonald, Lynn, and Florence Nightingale. Collected Works of Florence Nightingale : An Introduction to Her Life and Family, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2002.

"Florence Nightingale." Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 13 Jan. 2021.

“‘Cassandra’ by Florence Nightingale .” Florence Nightingale Museum, www.florence nightingale.co.uk/cassandra-by-florence-nightingale/. Accessed 18 Sept. 2023. |

Jacqueline Waugh |

| 1852 | Female Footbinding in ChinaFootbinding is the process of wrapping bandages around a young girl’s feet to prohibit its natural growth. The achieved formation would break the arch and bend the toes underneath the sole of the foot. Long bandages would then be wrapped around to keep the toes in place. Binding typically began at ages four or six, but it would sometimes occur as late as age twelve. Sides effects of this unnatural process included gangrene and paralysis; it also limited mobility. Based off the ideal of the dainty feet of dancers, this morbid beauty standard originated in China during the 10th century until being banned in 1949. While binding’s primary purpose was strictly aesthetic, it evolved into a mark of prestige and class status. Throughout the Ming (1368- 1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, bound feet were believed to be essential for a good marriage as they signified fertility and obedience. As the custom became a societal norm, the motivation behind binding shifted yet again. Women without bound feet were seen as ill-bred and difficult. Despite the painful and self-detrimental process, women continued to bind their feet to avoid societal scorn. Around the turn the end of the 19th century, China fell under the influence of Western cultures. Foot binding was seen as cruel and oppressive from this outside perspective—especially in the view of Western women. Thus began a movement against the tradition which quickly fell out of fashion. The end of the Qing dynasty accompanied the end of foot binding. Florence Nightingale mentions this process in her essay “Cassandra” as an example of socially constructed restrictions placed on women.

Additional Readings: Schiavenza, Matt. “The Peculiar History of Foot Binding in China.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 17, Sept. 2013. Shepherd, John. Footbinding As Fashion: Ethnicity, Labor, and Status in Traditional China. University of Washington Press, 2018. Tiffany Marie Smith. “Footbinding.” Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, 2020. |

Jacqueline Waugh |

| Oct 1853 to Feb 1856 | Crimean WarThe Crimean War was fought from October 1853 – February 1856 on the Crimean Peninsula, a peninsula lying between the Black Sea and Sea of Azov in Eastern Europe. The conflict happened between the Russians, British, French, and Ottoman Turkish. Arising from a conflict over Russian demands to exercise protection over the Orthodox subjects of the Ottoman Sultan living in Crimea. The Ottoman Turks were supported by Britain who launched a fleet to Constantinople, and successive victories and defeats ended in a sort of stalemate. Threatened by Austrian involvement on the side of the British and Ottomans, Russia entered peace negotiations and settled on March 30, 1856 with the Treaty of Paris. The Black Sea was neutralized and the Danube River was opened to all international shipping. Later historians and contemporary writers found the Crimean War to be managed and commanded poorly from both sides of the conflict. Disease ran rampant and accounted for 250,000 casualties out of the estimated 600-650,000. Mary Seacole was one of the many British citizens appalled by the conditions when news reached the public and without support of Britain’s War Office, financed the trip to the war herself and opened a field hospital and officer’s club for the soldiers at field. Crimea and the Crimean Peninsula has a long history as a boundary between the classical world and the steppe, a meeting point of what we inherit as western culture and eastern culture. Great powers have historically been active here, from the Greeks to Romans, the Ottoman Empire, as well as the Golden Horde through it’s time as a khanate. Russia and Ukraine are currently keeping war alive in this area as well – a testament to the lasting importance of this tiny island as a meeting ground for great powers, and the Crimean War is argued by some scholars to be the first outbreak of ‘total war’. Works Consulted and Further Readings Crimean Peninsula | Map, Facts, & Location | Britannica. 13 Sept. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Crimean-Peninsula. Crimean Peninsula -- Britannica Academic. https://academic-eb-com.er.lib.k-state.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Crimean-Peninsula/27904. Accessed 15 Sept. 2023. Crimean War | Map, Summary, Combatants, Causes, & Facts | Britannica. 16 Aug. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/Crimean-War. “THE CRIMEAN WAR: A History.” Kirkus Reviews, vol. LXXIX, no. 3, Feb. 2011. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/central/docview/915738269/abstract/D674F09E85A1413APQ/3. “The New Crimean War: Peninsula Is Both a Playground and a Battleground, Coveted by Ukraine and Russia.” Toronto Star, 6 Aug. 2023, p. IN.1. |

Ty Ratzlaff |

| 2 Oct 1853 to 30 Mar 1856 | Crimean War

ArticlesStefanie Markovits, "On the Crimean War and the Charge of the Light Brigade" |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1854 | The Big Stink: A Look at the Thames RiverConstantly at war within itself, Victorian London embodied a stark contrast of housing extreme wealth as well as extreme poverty. Outward signs of this dichotomy can be seen from looking at something as simple as the Thames River, both a flourishing facet of London in terms of transportation and commerce. Frederick Engels in his cry against the rise of industrialization and capitalism The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 describes the view of the Thames River as “…so impressive, that a man cannot collect himself, but is lost in the marvel of England’s greatness before he sets foot upon English soil” (Engels). While large factories, warehouses, ships, and wharves inhabited a part of the Thames River, simultaneously there existed huts, homeless populations, and extreme poverty. It was a place of great wealth, but the workers on the Thames were subject to floods, poor wages, and long hours. Richard Jones, esteemed London tour guide notes just the appearance of the Thames serves as a “stark reminder of the deep inequalities that plagued Victorian society” (Jones). A destitute population of workers carrying the burden of a few wealthy is the picture the river painted. Not only did this marked river carry a wide range of goods and people, but it in and of itself was disjunct. Once described by Charles Dickens as having “tawny lights” and “shimmering stars” the river was severely polluted by sewage and factory waste. It caused a scandal dubbed “The Great Stink” in which members of parliament had to be evacuated due to the rising stench and lack of cleanliness in the river. This later led to the first sewage system established in London. A hotbed of commerce and a symbol of wealth, the Thames River served as a reminder of the economic gains of the industrial revolution as well as the cost of sanitation, the pains of the working class, and overall great divide in Victorian London. Article: Jones, Richard. “The 19th Century River Thames.” Image: Caricature: Faraday Giving His Card to Father Thames. “And We Hope the Dirty Fellow Will Consult the Learned Professor.” Wellcome Collection, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.24801758. Accessed 8 Sept. 2023. Additional Articles/ Books: Allen, Michelle Elizabeth. Cleansing the City : Sanitary Geographies in Victorian London. Ohio University Press, 2008. Doran, Susan, et al. Royal River : Power, Pageantry and the Thames. Scala Books with the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, 2012. Russell, Malcolm, and Matthew Williams-Ellis. Mudlark'd. : Hidden Histories from the River Thames. Princeton University Press, 2022 Mentor Text: ENGELS, FREDERICK. Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844. DOUBLE 9 BOOKS, 2023.

|

Robyn Logan |

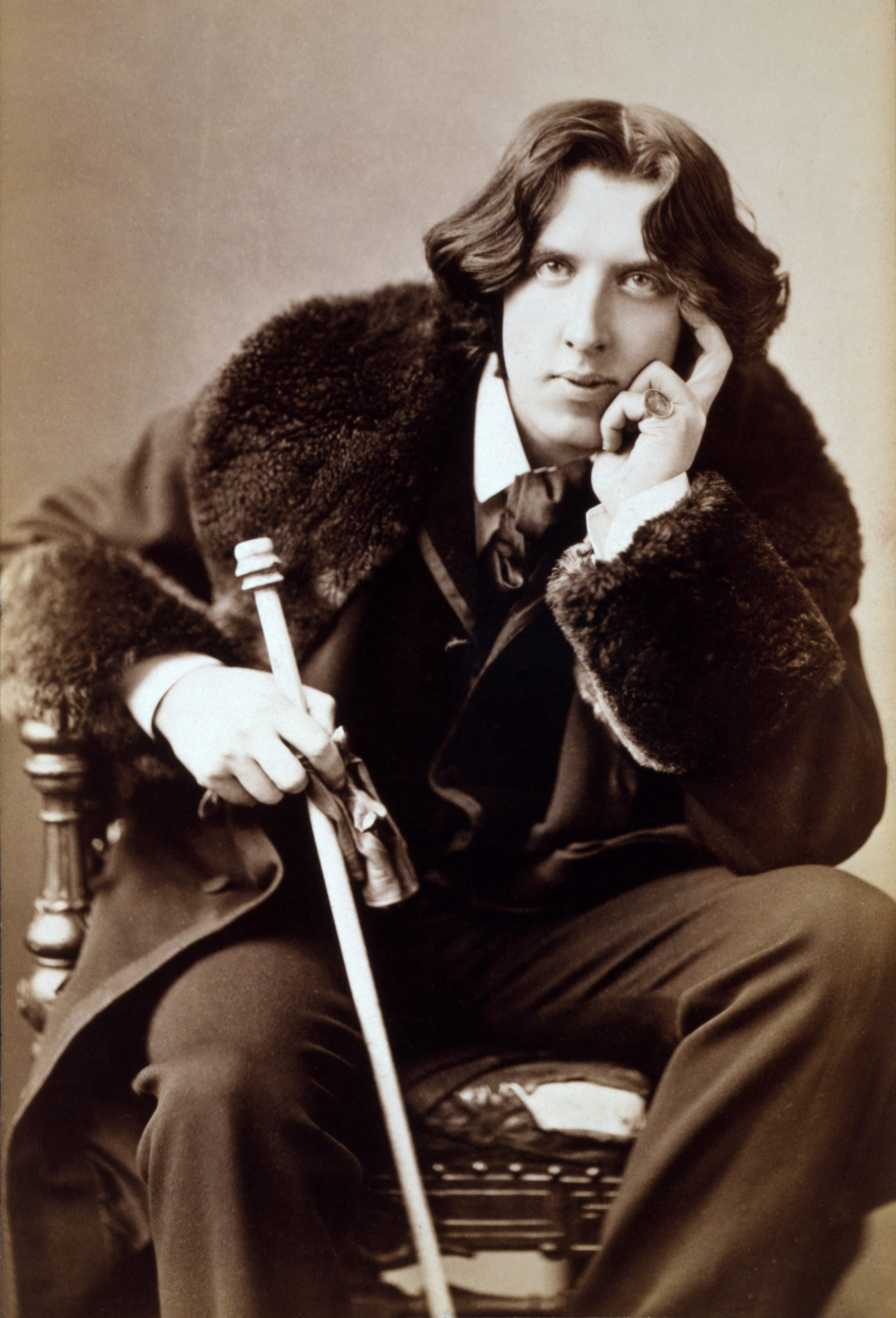

| The middle of the month Autumn 1854 | Oscar Wilde and the Failure to be EarnestUnlike many authors who are honored for their writing well after they have died, Oscar Wilde enjoyed a life of praise and social acceptance as a witty and talented man whose many works and Aesthetic lifestyle set him apart. Though his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, was a hit despite its controversial nature, Wilde’s true successes came from his role as a playwright of social comedies. In his 1895 play, The Importance of Being Earnest, Wilde’s two protagonists lead secret double lives that allow them freedom from responsibility and family and help them to pursue the relationships that they ultimately end up having by the end of the play. In Wilde’s comedy, the act of living a double life is described as being a “Bunburyist”, which refers to one of the leading character’s fake friend who is constantly sick and on the brink of death. Like his protagonists in the comedy, Wilde lived a secret double life and took part in his own form of Bunburyism. Though he was married to Constance Lloyd and went on to have two sons, Wilde lived out his homosexuality behind closed doors with several lovers, most notably, Lord Alfred Douglas. When Douglas’ father, who was the Marquess of Queensberry, found out about Wilde and his son’s secret affair, he became enraged and sued Wilde for criminal libel (Beckson). After he was found guilty, Wilde went on to serve two years of hard labor. When he was finally released from prison, the once famous and popular author was publicly shamed, bankrupt, and suffered from health problems as a result of his imprisonment. The contributions he had made to literature weren’t enough to return him to his status as a witty and beloved artist in society. Instead, Wilde died--with only a few close friends around him--from acute meningitis, disgraced and living away from home in France (Beckson). Image: Napoleon Sarony. Oscar Wilde. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oscar_Wilde. Additional Readings: Kaplan, Morris B. “Literature in the Dock: The Trials of Oscar Wilde.” Journal of Law and Society, vol. 31, no. 1, 2004, pp. 113–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1410445.

Reinert, Otto. “Satiric Strategy in the Importance of Being Earnest.” College English, vol. 18, no. 1, 1956, pp. 14–18. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/372763. Sale, Roger. “Being Earnest.” The Hudson Review, vol. 56, no. 3, 2003, pp. 475–84. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3852689.

|

Alyssa VanWey |

| 1855 | Lola Montes“When you met Lola Montes, her reputation made you immediately think of bedrooms” wrote Aldous Huxley in regards to Lola, a famous dancer, courtesan, and many other things. The history of Lola Montes seems steeped in mystery – her own autobiography is considered by some scholars as utter bologna, and the specifics of her life are difficult to pin down due to press coverage from her heyday leaving truth behind for tantalizing stories. A sex symbol to some and an inspiring dancer to others, while the details aren’t all clear Lola Montes left a mark on the entertainment industry. Montes was originally born Elizabeth Rosanna Gilbert on February 17th, 1821 in Ireland. She spent the majority of her childhood in India as her father was in the military, before receiving most of her schooling in Scotland and England. She married an army lieutenant herself before separating after five years, then commencing her career as a dancer in 1843. She seems to have been a hit very quickly, and romances with musicians seems to have worked her career along as well. She toured England, France, and Germany where she met Louis I of Bavaria and commenced a lengthy mistress-ship resulting in a castle and titles of Baroness and Countess. Montes was influential enough for Louis to make liberal and anti-Jesuit policies – but also supposedly his infatuation with her resulted in the collapse of his regime and revolution in 1848. She had a short marriage following, and then settled in the United States and performed major cities. The mention here of Lola visiting the hotel in Crimea would have likely been a performance for the morale of soldiers. Although Montes’ life is shrouded in mystery and exaggeration, her legacy is clear in the various film, theatre, and literary productions about her in up to the (relatively) present day. Works Consulted and Further Readings Burns, Mickey. “Lola Montes.” Cineaction, no. 40, 1996, pp. 38-0_3. Lola Montès. Directed by Max Ophüls, Gamma Film, Gamma Film, Florida Films, 1955. Lola Montez | Irish Dancer, Courtesan & Actress | Britannica. 20 July 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lola-Montez. The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Magnificent Montez, by Horace Wyndham. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/21421/21421-h/21421-h.htm#pic_05. Accessed 15 Sept. 2023. |

Ty Ratzlaff |

| 10 May 1857 to 20 Jun 1858 | Indian Uprising

ArticlesPriti Joshi, “1857; or, Can the Indian ‘Mutiny’ Be Fixed?” Related ArticlesJulie Codell, “On the Delhi Coronation Durbars, 1877, 1903, 1911″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| 28 Aug 1857 | Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857

ArticlesKelly Hager, “Chipping Away at Coverture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857″ Related ArticlesRachel Ablow, “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act” Jill Rappoport, “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property” |

David Rettenmaier |

| The end of the month Summer 1857 | Marriage and the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857While the issue of marriage and relationships play a large part in Oscar Wilde’s 1895 play, The Importance of Being Earnest, the topic of divorce and unhappy marriages also appears as a supporting theme in the comedy. As mentioned by one of the leading characters, Algernon Moncrieff, “The very essence of romance is uncertainty…Divorces are made in Heaven.” Although Wilde often makes comments on relationships and social issues, the topic of divorce was especially relevant to the audience of his time as more and more people made the decision to divorce their spouse. According to the Report of Royal Commission on Divorce and Matrimonial Causes 1912-1913, the years before and after the publication of Wilde’s play saw a 17.9% increase in divorces between the years of 1894-1898 (Savage). Prior to the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, those who wanted to separate from their spouse would have to get permission from the ecclesiastical courts that would require the couple to jump through several hoops to finally obtain their legalized divorce (Poovey). As a result of the Matrimonial Causes Act, divorces could be granted in a secular court, but remained an expensive matter for the separating couple. Even though the act helped to make divorces easier and more convenient, divorces were still a challenging experience for the women who were involved in the separation. Since women were not seen as their own legal person for much of this era, they needed to provide additional information as to why they wanted a divorce. Unlike men who could divorce their wife over a reason like infidelity, women needed to also prove that their husband had been abusive, had deserted them, or had committed crimes of incest or rape in addition to them being unfaithful (Layton, et. al). Not only did this, but due to the Custody of Infants Act of 1839, husbands were awarded custody of their children no matter the circumstances. If a man decided to divorce his wife, she would not only lose her status and security, but most likely her children as well. Image: Vasili Pukirev. The Unequal Marriage. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasili_Pukirev. Additional Readings: Holmes, Ann Sumner. “The Double Standard in the English Divorce Laws, 1857-1923.” Law & Social Inquiry, vol. 20, no. 2, 1995, pp. 601–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/828954. Shanley, Mary Lyndon. “‘One Must Ride behind’: Married Women’s Rights and the Divorce Act of 1857.” Victorian Studies, vol. 25, no. 3, 1982, pp. 355–76. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3827203. Wolfram, Sybil. “Divorce in England 1700-1857.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, vol. 5, no. 2,1985, pp. 155–86. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/764190.

|

Alyssa VanWey |

| 28 Jun 1858 | Control of India passes from the East India Company to the Crown

On June 28th, 1858, The British Empire annexed the Indian subcontinent. Prior to this, the East India Company had controlled India as an enterprise. The Great Uprising of 1857 derailed this business, and the Crown insisted upon direct control of the country. The British continued their policy of non-intervention in social matters, but would not officially grant India independence until 1947. The 1857 Indian Rebellion was spurred by a number of factors, including British social reforms like Macaulay's education reform. Many Indians resented these policies, and felt that the British were attempting to dismantle their social and cultural systems and norms. Company rule was particularly insensitive toward native religions, and many Indians considered this style of governance to be a total failure.

Dash, Mike. “Pass it on: The Secret that Preceded the Indian Rebellion of 1857.” Smithsonian Magazine, 24 May 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pass-it-on-the-secret-that-preced.... Accessed 17 September 2023.

“East India Company and Raj 1785-1858.” UK Parliament, https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/le.... Accessed 17 September 2023.

https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199791279/... |

Drew Bellamy |

| 1 Dec 1860 to 3 Aug 1861 | The Publishing of Charles Dickens’ Periodical All the Year RoundAll the Year Round was a periodical publication previously titled Household Words which ran from 1850 to 1859, then taken over by Charles Dickens and W.H Wills starting in 1859 (with Dickens owning seventy-five percent and Wills only twenty-five percent.) Though Dickens had contributed many journalistic pieces and had serialized his novel Hard Times in the previous journal, his priorities shifted in taking over All the Year Round. Many new periodicals were coming onto the scene, with 114 magazines coming out in 1859 and many more in the years following. Safe to say, Dickens had a lot of competition when creating this new periodical, trying to tap into the aesthetic of Household Words while changing its format to attract a broader audience. While the first journal emphasized more social commentary in the front pieces of the periodical, Dickens instead focused on placing authors’ serial fiction in the front, of course including his own compositions. Dickens started with publishing a re-installment of A Tale of Two Cities to boost initial sales. He then first published his famous novel Great Expectations starting December 1, 1860 and running through August 3, 1861 in thirty-six weekly installments. It was then published as a three-volume novel in October 1861. Along with his own publications, Dickens’ good friend Willkie Collins’ published many works in the periodical, including serializing his novel The Woman in White. Many other authors (such as Elizabeth Gaskell) published in the periodical, with most authors being unequally paid based on gender and Dickens’ preference rather than the success of the novel. Still, in total twenty-seven novels appeared during the years Dickens edited it. Along with changing the format, after Dickens and Wills became part owners of the periodical they also covered all expenses to get maximum profit and maximum coverage. The pair circulated up to 300,000 periodicals around Christmas for their special editions and were regularly around 100,000 copies—more than double that of Household Words. Dickens composed and edited All the Year Round until his death in 1870. After Dickens’ death his son Charles Dickens Jr. took over and took full ownership, buying out Wills’ twenty-five percent share. Dickens Jr. remained the chief editor until 1888, and the periodical officially ceased publication in 1893. Works Cited: Allinham, Phillip V. "All the Year Round: An Introduction." The Victorian Web, 2015, https://victorianweb.org/periodicals/ayr/intro.html. For further reading: - All the Year Round: an Introduction - Archival Editions of All the Year Round - Installments and Chapter Numbering of Great Expectations in the First Book Publication |

Lindsey Bergner |

| 3 Aug 1861 | ***SPOILER ALERT*** “I saw the shadow of no parting from her:” The Alternate Endings of Great ExpectationsWhen Dickens’ conceived the original ending for Great Expectations, it had a much different outcome than the revised ending readers of the novel are familiar with. The original ending written in June of 1861 saw Pip and Estella meet again, but Pip has knowledge that she has remarried after her first husband’s death. Instead of being set at the Satis house as in the revised ending, Estella is in a coach and just briefly speaks to Pip. They have nothing but cordial feelings in the brief encounter, they part, and the story ends. Dickens shared the draft with his friend Edward Bulwer-Lytton who in turn encouraged a happier conclusion for his loyal readers. Since Dickens was the chief editor and owner of his periodical, he relied on fan reactions and was known to change a story mid-way through to appease fans while still upholding his original idea. In the revised ending, the story is set at the ruins of the Satis house with the mist mirroring the marshy scene at the start of the novel. In this ending, Estella had still lost her first husband but had not remarried. As pictured, the revised original manuscript’s ending phrase also reads differently than the published one: “I saw the shadow of no parting from her but one.” The “but one” addition changes the meaning of the revised ending, seeming to mean that Pip will part from Estella this once and see her no more. While it could instead mean parting in death, it leaves much less ambiguity than the revised, published ending. The final chapter was officially published August 3, 1861, and the last sentence read “I saw the shadow of no parting from her.” The elimination of “but one” leaves more ambiguity in the meaning of the ending. While most assume that this leaves Pip and Estella the opportunity of a romantic relationship, the truth of Dickens’ original ending may damper any hopes of a marriage between the two. If Dickens originally planned for Pip and Estella to remain unmarried, then it’s likely the revised ending does not mean Pip and Estella have a romantic relationship. The interpretation of the alternate endings is still up for debate. For further reading: - See page 508, Appendix A (in Penguin edition) for original ending - Charles Dickens’s Alternate Ending to Great Expectations - Museum with Original Manuscript - “The Altered Endings of “Great Expectations”: A note on Bibliography and First-Person Narration “Last Words on Great Expectations: A Textual Brief on the Six Endings” |

Lindsey Bergner |

| 1862 | Publication of Rossetti's "Goblin Market"Published in 1862 in a collection entitled Goblin Market and Other Poems, Christina Rossetti’s poem “Goblin Market” was widely well-received by its readers despite having little commercial success initially. Rossetti originally composed this poem in April 1859, which she named “A Peep at the Goblins – To MFR.” The dedication likely refers to Rossetti’s sister, Maria Francesca Rossetti, who, along with Rossetti, volunteered at the St. Mary Magdalene house in Highgate (more formally known as the London Diocesan Penitentiary). The sisterly bond within the poem can likely be seen as a reflection of Rossetti’s own relationship with her sister, considering her original dedication.

While many scholars accept the poem to be response to the ‘fallen woman’ concept both in literature and society, Rossetti’s brother, Michael William Rossetti claimed that “[he] more than once heard Christina aver that the poem has not any profound or ulterior meaning--it is just a fairy story” (Bell). Many Victorian readers agreed with this assessment, although more modern scholars see her work as reaction to her work with the St. Mary Magdalene house. Rossetti volunteered at the penitentiary from 1859 to 1870, which housed and gave work to many women who were former sex workers. Many critics suspect that her work with these women inspired some of the themes within “Goblin Market,” such as female sexual desire and the redemption of the ‘fallen woman.’

Goblin Market and Other Poems was Rossetti’s first published volume of poetry and was printed under her own name. Before this, Rossetti had published a few other poems in magazines, including The Germ and Macmillan's Magazine, under the pseudonym Ellen Alleyn. The Goblin Market and Other Poems collection also featured illustrations of scenes from the poems drawn by her brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Further Reading “Advertisement for a House for “Fallen Women” from the Morning Post.” The British Library, www.bl.uk/collection-items/advertisement-for-a-house-for-fallen-women-f…. Bell, Mackenzie. Christina Rossetti; a Biographical and Critical Study. Boston, Roberts Brothers, 1898, www.babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015002749755&seq=7. Roe, Dinah. “An Introduction to “Goblin Market.”” The British Library, 15 May 2014, www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/an-introduction-to-goblin-m…. |

Destiny Munns |

| 1867 | Marx’s Critique of Capitalism: Unmasking the Fetishism of Commodities and its ImpactThe industrial revolution marked a significant shift in the means of production, leading to what Karl Marx termed the “commodity” and the concept of “commodity fetishism.” In his analysis, Marx delves into the nature of commodities, how they disconnect people from their own labor, and how they can ensnare individuals in what he labels the “fetishism of commodities.” He also explores how this system affects the working day and deteriorates essential human functions. Marx doesn’t categorize all outcomes of human labor as commodities. He argues that it’s inherently human to adapt nature’s offerings for personal benefit. If someone, for instance, sews a jacket for personal use, it isn’t considered a commodity but rather a product with “use value” for the creator. It transforms into a commodity when it meets two crucial conditions set by Marx: it must satisfy a specific social need, and it must enter the complex capitalist market network to acquire an “exchange value.” According to Marx, capitalism complicates the production process to maintain a social structure that empowers capitalists. He holds capitalism responsible for alienating laborers from their fellow workers and the products they create. In earlier times, individuals crafted their own items and saw the entire production process from start to finish, taking pride in their completed product. However, in the capitalist system, factory workers often focus on a single monotonous part of producing a commodity and may never witness the finished product or use it themselves. To further simplify Marx’s idea, consider writing: in its simplest form on a page, one plus one equals two, and both the front-end and back-end processes are transparent and easily comprehensible. Yet, when this process becomes mechanized, the front-end results may be quicker, but the intricate back-end process involving zeroes, ones, and signals becomes invisible and requires specialists to understand. Marx argues that this complexity enables the bourgeoisie to exploit and commodify the proletariat. If consumers remain unaware of the harsh conditions and cruelty endured by children, women, animals, etc., in the production of certain goods, they may willingly purchase those products, even if they belong to the same class as the laborers who produced them. Marx famously stated that “therefore, the relations connecting the labour of one individual with that of the rest appear . . . as what they really are, material relations between persons and social relations between things” (Parker, Critical Theory 382). This phenomenon fosters what Marx refers to as “commodity fetishism.” The shroud of secrecy surrounding the production process imparts a “mystical character” (Parker, Critical Theory 381) to commodities. For example, phones are designed for making calls, sending messages, and taking selfies, yet consumers often prioritize owning the latest version, despite its negative social and environmental impacts. Even if their current phones fulfill all the expected functions, this desire for the newest version exemplifies their “commodity fetishism.” In essence, Marx’s analysis highlights how capitalism, with its complex production processes and alienation of laborers, can lead to a societal obsession with commodities, often at the expense of social and environmental well-being.

Further Reading Suggestions: Parker, Robert. Critical Theory: A Reader for Literary and Cultural Studies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. Parker, Robert. How to interpret literature: critical theory for literary and cultural studies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. Mahmoud, Mustafa. Why I Rejected Marxism. Dār al-Ma’ārif, 1976. |

Maryam ElZayat |

| 15 Aug 1867 | Second Reform Act