By Spencer Adelmann

At the young age of twenty-two, Bernard Higham demonstrated a keen eye for detail and a nuanced understanding of Victorian art in his illustrations for Catherine Louisa Pirkis’s The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective, first published in 1893. Born in Kent, England, in April of 1871, Higham left an enduring mark on visual storytelling through his artistic contributions to the detective fiction genre. While little is known about Higham himself, a close analysis of his illustrations allows us to draw connections between his work and the broader artistic and literary movements of the time, offering a fascinating glimpse into fin de siècle culture. Through an examination of his style and technique, we gain insight into the ways that images were used to complement Pirkis’s written narrative. Furthermore, exploring the relationship between Higham’s illustration and Pirkis’s text allows us to consider how this combination of written text and visual art may have enhanced the Victorian reader’s experience. Lastly, investigating Higham’s artistic portrayal of Loveday Brooke demonstrates the influence of Higham’s illustrations on the representation of female detectives in Victorian literature.

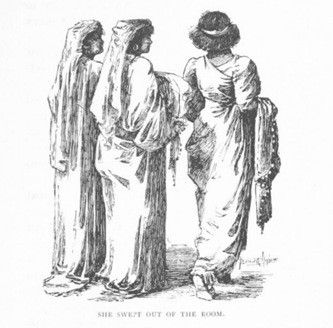

The fin de siècle is widely recognized as a golden age for book illustration.[1] Bernard Higham embodies this high level of achievement, providing readers with visual cues that bring the stories to life. His work clearly echoes the work of Pre-Raphaelite artists, who sought inspiration from the late Medieval period, emphasizing detailed patterns and symbolic imagery in their work. This influence can be seen in Higham’s intricate compositions and motifs, which often feature decorative borders and elaborate details to create a striking visual effect.[2] Higham’s work also reflects the Arts and Crafts movement, which emphasized artworks as functional objects using traditional techniques of craftsmanship.[3] His attention to detail is evident, for example, in an illustration for “A Princess’s Vengeance.” Here, Higham creates textures, such as the woven fabric of the dresses worn by Mrs. Druce with her two attendants (Figure 1). His illustrations reflect the Arts and Crafts movement’s belief that beauty and function should go hand in hand, thus making the text more engaging and accessible for readers.

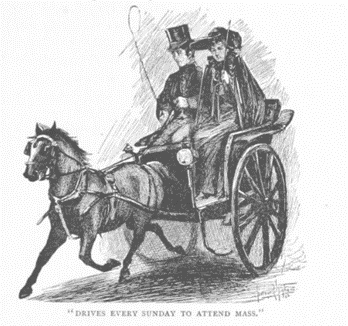

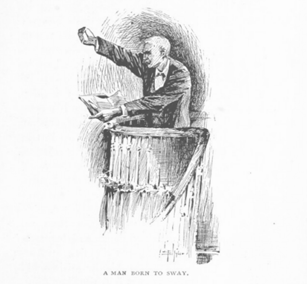

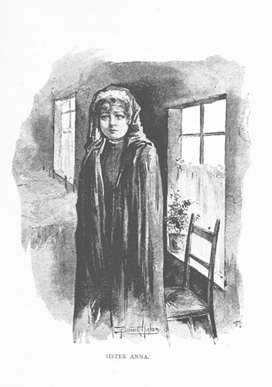

To add depth and dimensionality to his illustrations, Higham used crosshatching, a shading method that involves overlapping lines to create a textured effect, as seen in “The Ghost of Fountain Lane” (Figures 2 and 3). This technique was commonly used by book illustrators of the period, such as George Cruikshank and Hablot Knight Browne (also known as “Phiz”)[4] and was associated with other artistic mediums of the time, such as in engraving and etching.[5] In addition to crosshatching, Higham also employs the artistic technique of washing to create a water-like border around some illustrations, as seen in “The Redhill Sisterhood” (Figure 4). This technique creates a dreamlike atmosphere that draws the viewer’s attention to the central image. This attention to detail and atmosphere is reminiscent of the works of other notable Victorian illustrators, such as Arthur Rackham and Kate Greenaway, two leading figures of this golden age of British book illustration.[6] Higham’s ability to combine crosshatching and washes in his illustrations not only showcases his technical skills but also enhances the reading experience by creating a rich and immersive world to explore. In “A Princess’s Vengeance,” for example, Higham’s illustration of Loveday Brooke seated underneath a large plant in a contemplative posture captures the sense of foreboding and mystery that permeates the story, as shown in Figure 5.

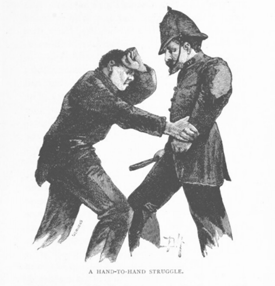

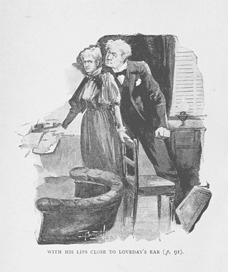

Higham's illustrations for Loveday Brooke not only follow the artistic and literary conventions of the Victorian fin de siècle and showcase Higham’s technical skill but also work in unison with Pirkis’s text to elevate the reader’s engagement. The illustrations provide visual clues to assist readers in imagining the scenes and characters, which influences the tone and ambiance of the stories. In “The Redhill Sisterhood,” for example, Higham’s illustration of a thief and policeman struggling, captioned “a hand-to-hand struggle,” intensifies the story’s sense of danger and intrigue (Figure 6). Similarly, in “The Murder at Troyte's Hill,” Higham’s illustration of the dramatic scene involving Mr. Craven and Loveday Brooke, captioned “his lips close to Loveday’s ear,” heightens the story’s tension by adding another representation of menace (Figure 7). In essence, Higham’s illustrations complement and expand Pirkis's text, resulting in a unified and engrossing experience for readers.

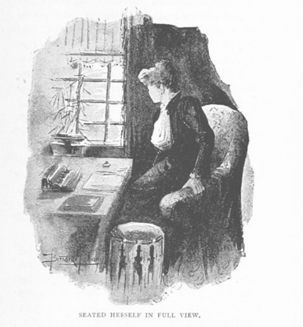

Higham also enhances Pirkis’s text by highlighting the character of Loveday Brooke herself. Brooke is portrayed as a confident and capable detective who actively investigates clues and confronts suspects. In “The Redhill Sisterhood,” for instance, Higham portrays Brooke sitting upright at her desk in her office, thus accentuating her intelligence and skill in a male-dominated field (Figure 8). In this way, Higham’s illustrations offer insight into the changing attitudes towards women in Victorian society. The Loveday Brooke series was published during a time when the feminist movement was gaining momentum in Britain, and the emergence of professional women challenged traditional gender roles. Higham’s illustrations depict Brooke as a strong, confident woman who is the equal or better of any male detective. It is also worth noting, however, that Higham's illustrations do not always challenge traditional gender roles, as they often depict Brooke in stereotypically feminine attire. These depictions suggest that while women were gaining more opportunities and visibility in society, gender norms and expectations still exerted a significant influence on women’s lives.

Bernard Higham’s illustrations for Catherine Louisa Pirkis’s The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective are a testament to his mastery of Victorian artistic techniques and his ability to enhance the narrative through visual storytelling.

Notes

[1] Gwen Vredevoogd, “Book Illustration in the Victorian Age,” Virginia Libraries 59, no. 1 (2013): 15.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 15–16.

[4] “Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (February 13–November 27, 1841).” The Victorian Web, last modified December 16, 2020, https://victorianweb.org/.

[5] Simon Cooke, The Moxon Tennyson: A Landmark in Victorian Illustration (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2021), 203.

[6] Paula S. Fass, Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood in History and Society. Volume 3, Children and Childhood (New York: Macmillan, 2004), 43.

Figure 1. Higham, Bernard. “She Swept Out of the Room,” The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (London: Dover, 2020), 111.

Figure 2. “Drives Every Sunday to Attend Mass,” The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (London: Dover, 2020), 159.

Figure 3. “A Man Born to Sway,” The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (London: Dover, 2020), 172.

Figure 4. “Sisters Anna,” The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (London: Dover, 2020), 73.

Figure 5. “Beside the Big Palm,” The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (London: Dover, 2020), 109.

Figure 6. “A Hand-To-Hand Struggle,” The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (London: Dover, 2020), 93.

Figure 7. “With His Lips Close to Loveday’s Ear,” The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (London: Dover, 2020), 62.

Figure 8. “Seated Herself in Full View,” The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (London: Dover, 2020), 86.