By Bridget Schmid

The Ludgate Monthly, published from May 1891 to February 1901, was a London-based magazine. In the 1891 introduction, then-editor Philip May referred to the periodical as “an illustrated family magazine” with the goal of adding more—and better—artwork in each issue.1 May promised that readers of all ages would enjoy a variety of interesting and educational articles, including some with a “good cause to plead.”2 This included one of the magazine’s most important serials, Catherine L. Pirkis’s The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (1893). Pirkis’s first six stories in the series were published in The Ludgate Monthly from February to July of that year, but the seventh, titled “Missing!” wasn’t printed in the magazine until after the book edition appeared in 1894. This essay will study the complex roles of women in The Ludgate Monthly in comparison to Pirkis’s female detective. The character Loveday Brooke presents a progressive portrait of a professional woman while the magazine itself offers an uneven view of women’s roles as being both progressive and conventional.

The first edition of The Ludgate Monthly was published in May 1891 with Philip May as the editor. Some articles of that first month included “England, Home, and Beauty” by E. Gowing Scopes and short stories such as “Laura and Her Rival” by Leopold Wagner. This issue of the magazine, as with each following installment, was comprised of various features such as fiction, songs, poetry, and historical accounts. Multiple advertisements were also incorporated. In 1892, May reported that The Ludgate Monthly had the largest circulation of a threepenny magazine in the United Kingdom and thanked those who gave their used copies to the poor.3 He also revealed that many well-known British writers had contributed to the magazine and that the illustrations were well received.4 May was pleased with the magazine thus far, but many readers had a complaint: they wanted their articles weekly! So a penny magazine was founded with thirty-two pages—and a few illustrations—per week, edited by Charles Ogilvie. Unfortunately, The Ludgate Weekly was short-lived, lasting only from March 1892 until October of that same year.5

Throughout every change the magazine underwent, it highlighted gender roles, with women writers often contributing articles on housework and child-rearing. However, a more feminist perspective was introduced into the magazine with the publication of The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective. From this point forward, The Ludgate Monthly demonstrated a duality in its treatment of women’s issues: Loveday showcased a progressive professional woman, but other articles offered up images of the standard, conventionally feminine women of the time. Stories in the Loveday serial were mixed with regular series such as “Whispers from the Woman’s World” in which Florence Mary Gardiner gave advice on fads such as curtain fabrics or the latest, most fashionable hat. In the 1893 edition of the series, Gardiner says that the pages she has written “have been received with such kindly appreciation by the lady readers of The Ludgate Monthly.”6 By this time, the magazine was growing in popularity, and Gardiner’s series seemed essential to its success.

The conventional ideas of Gardiner are echoed in the magazine’s advertisements, which were seemingly geared towards housewives. The first edition of the magazine included advertisements for corn flour, a “household requisite”; liquid gold to decorate slippers; complexion cream; and a course for learning shorthand, a skill that was “rapidly becoming fashionable” and that “every lady” should know.7 Additional products marketed to ladies included sewing machines, tablecloths, perfume, and corsets (Figure 1).

Yet, as the subtle references to professional skills suggested, The Ludgate also incorporated positive and empowering stories for women interested in pursuing professional careers. One article, “Famous Women,” which appeared in the November 1892 issue, praised professional women and their inspirational work. One of these profiles was of Henrietta Eliza Vaughan Palmer, who wrote under the pseudonym “John Strange Winter.” Palmer decided to “adopt a literary career” at the age of eighteen; the prejudice against women pursuing literary careers evidently did not stop her, as her work was wildly successful, and she became the first president of The Writer’s Club.8

Pirkis’s Loveday Brooke likewise promoted women’s rights and employment opportunities. Loveday defied norms by working as both a successful career woman and a feminist. From the first of her stories onward, she embodies this mindset and implies that her readers should do so as well. In this way, Loveday Brooke modeled how to overcome prejudice and become a professional woman in her field. In the introduction to The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Michele Slung explains that women of the Victorian era often found work as governesses. If they did not follow that occupation, they could become dressmakers, laundresses, artisan workers, or other domestic laborers. The one occupation that women did not partake in was that of the detective.9 But Loveday disregarded those barriers, choosing an occupation she was good at and enjoyed. She is portrayed in her stories as having “ingenious” theories, one trait a dressmaker, for example, would most likely not need to possess.10 Women readers no doubt were thrilled keeping up with Loveday’s adventures and perhaps thought of her as a role model for whom they might become.

“Ephemeral Journalism and Its Uses,” an article written by Sally Mitchell in 2009, further suggests why Loveday Brooke was so groundbreaking. Mitchell explains that women writers of the time “supported themselves (if not very well) with a little staff work and a lot of free-lance paragraphs on fashion, society, and ‘women’s topics.’”11 Mitchell quotes Florence Fenwick Miller from 1896, saying, “most of the original and capable writers of the present day are comparatively little known to the public.”12 Miller went on to explain that this is because the writers had their works published in newspapers rather than books.13 Pirkis, like her heroine, defied the odds. The fact that Loveday was eventually published in book form suggests that there was something special about Pirkis and her subject matter.

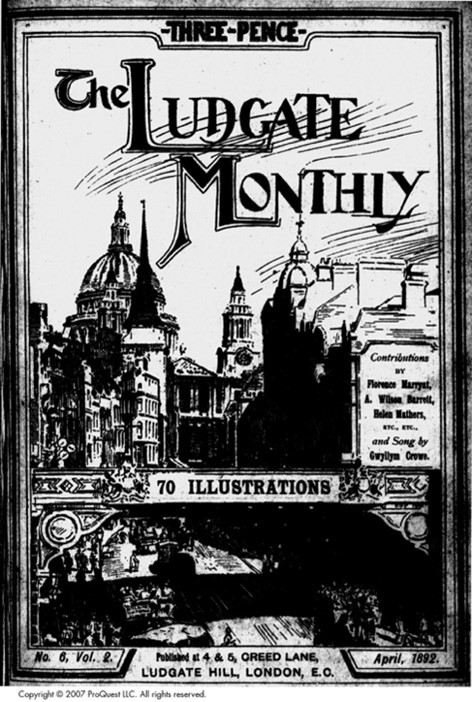

Key to the success of The Ludgate—and Pirkis’s Loveday Brooke series—was its use of illustrations. Some covers of The Ludgate Monthly even stated exactly how many illustrations were in the issue (Figure 2). “Whispers From the Woman’s World” often included an illustration on every page. The Loveday Brooke series also included drawings that depicted the heroine as a skillful professional. The illustrations convey that she is known to “outdistance her male colleagues” in the way she solves mysteries.14 One story in particular, titled “The Black Bag Left on a Doorstep,” shows Loveday with Mr. Dyer, the chief of detectives of Lynch Court. Here she is “explaining the whole thing” after solving a crime by herself (Figure 3).15 In spite of her gender, Loveday is obviously very good at what she does, but she also uses her gender to her advantage. She does not tell people her occupation, and they do not suspect her of being a detective. Loveday’s progressive thinking is at play here: she is able to solve crime without suspicion or prejudice.

The writings about Loveday Brooke eventually ended in 1894, but The Ludgate Monthly stayed in print for a few more years. Another change was made to the publication when it was renamed in November 1895 simply as The Ludgate. This edition introduced new staff and included articles that gave readers some insight into the lives of its contributors. From this time until the magazine’s closure in February 1901, The Ludgate maintained its original focus on publishing engaging illustrations, stories, and interviews, content largely aimed at women. Because Victorian society presented women with contradictions about how they should lead their lives, the magazine, too, offered both conservative and progressive models of behavior. Loveday Brooke gave special attention to professional and feminist women, while the magazine’s advertisements and other features offered models of conventional femininity. Both are important to our understanding of the time period and the history of feminist thought.

Figures

Figure 1. “Advertisement,” Ludgate Monthly, May 1891, 10.

Figure 2. “Cover,” Ludgate Monthly, April 1892.

Figure 3. “Loveday Explained the Whole Thing,” The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective, Ludgate Monthly, November 1892, 413.

Notes

- Philip May, “Introduction,” Ludgate Monthly 1 (May 1891): 22.

- Philip May, “Philip May Returns Thanks and Introduces The Ludgate Weekly Magazine,” Ludgate Monthly 2 (March 1892): 320.

- Florence Mary Gardiner, “Whispers From the Woman’s World,” Ludgate Monthly, November 1892, 157.

- “Advertisement,” Ludgate Monthly 1 (May 1891): 7, 16.

- M. G., “Famous Women Novelists,” Ludgate Monthly 4 (November 1892): 572–73.

- Michele Slung, introduction to The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective by Catherine Louisa Pirkis (New York: Dover, 2020), xiii.

- Catherine Louisa Pirkis, The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (New York: Dover, 2020), 26.

- Sally Mitchell, “Ephemeral Journalism and Its Uses: Lucie Cobbe Heaton Armstrong (1851–1907),” Victorian Periodicals Review 42, no. 1 (2009): 81.

- Slung, Introduction, xiv.

- Pirkis, The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, 25.