By Katherine Bruns

Even before real-life female detectives walked the streets of London, fictional representations of women as detectives offered a challenge to traditional Victorian gender boundaries. Officially, women were not employed as detectives by the Metropolitan London Police Force until 1915, but they were engaged in police work as early as 1883 to supervise female prisoners.[1] Around the same time, private detective agencies began to advertise the skills of their lady detectives. However, these women remained mysterious and anonymous. Despite the limited knowledge of Victorian female detective work in real life, fictional female detectives first appeared in the middle of the nineteenth century and continued to grow in popularity.[2] One of these fictional female detectives was created by Catherine Louisa Pirkis in 1893, when she serially published The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective in The Ludgate Monthly. As she took on a new disguise in each story, Brooke identified the particular qualities that granted women success in the detective role. By using disguise as an investigative tactic, Loveday Brooke performs the social expectation of femininity to successfully solve cases and infiltrate private life.

In the Victorian era, many believed that it was absurd for a woman to pursue a professional career. After all, as Mary Lyndon Shanley describes, Victorian society dictated that “women presided over the home, while men sallied forth into the public realm.”[3] Even in fiction, women often had to give an excuse for entering into the detective profession. As Adrienne Gavin notes, they might be “seeking to clear male relatives’ names” or attempting to “provide financially for incapacitated husbands.”[4] In contrast, Catherine Pirkis does not give Loveday Brooke an excuse for seeking employment as a detective. Rather, she simply provides an explanation, saying, “some five or six years previously, by a jerk of Fortune’s Wheel, Loveday had been thrown upon the world penniless and all but friendless.”[5] Even though Loveday needed to find a way to support herself financially, her distinctive skills were enough to justify her decision to become a detective. In fact, her employer, Mr. Ebenezer Dyer, “quickly enough found out the stuff she was made of, and threw her in the way of better-class work.”[6] Pirkis makes it clear that women bring unique qualifications to the detective role beyond the need for employment.

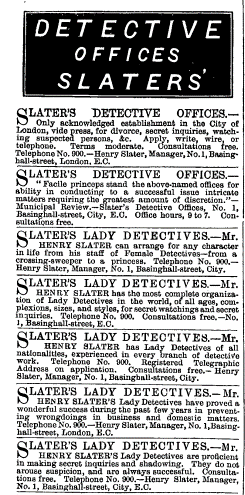

In addition to fictional examples like Loveday, advertisements in Victorian newspapers, periodicals, and legal journals made it clear that women could be successful in careers as private detectives. In particular, Slater’s Detective Agency was eager to advertise the performative skills of their female employees. Ads for this agency often appeared in a well-known legal periodical entitled The Solicitor’s Journal. Slater’s was advertised as early as 1889, noting that “secret enquiries” would be dealt with by “Female and Male detectives.”[7] The italicization of Female and Male shows that the agency already knew it was valuable to employ female detectives. By 1895, advertisements for this same agency focused almost entirely on female qualifications, even using the heading “Slater’s Lady Detectives.”[8] This advertisement gives a glimpse into the types of cases that these “Lady Detectives” typically investigate, noting that they have “proved a wonderful success during the past few years in preventing wrongdoings in business and domestic matters” (Figure 1).[9] It’s possible that the growing popularity of the female detective story, including Loveday Brooke, increased the demand for real-life women detectives.

Slater’s was clearly eager to highlight the female detective’s ability to disguise herself for each case. The same 1895 column of advertisements for “Slater’s Detective Offices” stated boldly that “Henry Slater can arrange for any character in life from his staff of Female Detectives—from a crossing-sweeper to a princess.”[10] Clearly, the ability for a detective to assume a disguise was an important, perhaps even expected, part of the job. The same advertisement column also highlighted the physical characteristics of women detectives, saying the agency could provide “all ages, complexions, sizes, and styles” and “all nationalities.”[11] By calling attention to the variety of women detectives that were available, Slater’s Detective Offices demonstrated to their audience that they understood the importance of secrecy and disguise as one of the unique benefits of female detective work.

Loveday Brooke shows how a female detective can use disguises to her advantage in her investigative work. Loveday’s roles include a housekeeper’s niece, an amanuensis, a nursery governess, and a lady house decorator—roles that could not be played by a man. In fact, she is often called to help with an investigation after the male police detectives have failed. For example, in “The Murder at Troyte’s Hill” the police detective Mr. Griffiths informs Brooke that she does not need to focus on details outside of the house because “every iota of fact on that matter has been gone through over and over again by [Griffiths] and [his] chief.”[12] Instead, Brooke is asked to “go straight into the house and concentrate attention on Master Harry’s sick-room, and find out what’s going on there.”[13] As a female detective, Loveday Brooke can investigate spaces that are inaccessible to male police detectives. Brooke’s roles and disguises also allow her to place herself in private home life without drawing suspicion, making her almost invisible.

Simply because she is a woman, Loveday fits naturally into typical female roles without adjusting her behavior. Though disguise is a crucial part of her job, Loveday does not seem to require very much instruction or detail about each role she is asked to perform. As Mr. Dyer, Loveday Brooke’s supervisor, describes each new case, he does not discuss her disguise until the end of their conversation, and even then, he only provides basic details. For example, in “The Black Bag Left on a Doorstep,” shortly before he sends her off, Mr. Dyer says, “I have arranged with the housekeeper there . . . that you shall pass in the house for a niece of hers.”[14] He notes that “naturally you have injured your eyes as well as your health with overwork; and so you can wear your blue spectacles.”[15] These simple details are all Loveday Brooke needs to carry out her investigation without arousing suspicion from the occupants of the house. She does not need to be a particularly skilled actress in order to accomplish her goal.

As a female working professional, Loveday’s class status makes her well-equipped to play a wide variety of roles, both in the domestic sphere and in other professional capacities. In “Drawn Daggers,” Brooke is allowed to select her own role to play, and she designs the ideal position for herself as a “lady house decorator.”[16] By emphasizing the “lady” title of this role, Loveday shows that she is uniquely qualified to investigate cases such as this. This disguise also allows her to retain her status as a professional. In Loveday Brooke’s words, this position is ideal because “I should interfere with no one, your family life would go on as usual, and I could make my work as short or as long as necessity might dictate.”[17] She recognizes her ability to investigate the case while staying invisible as normal life continues in the home. By mentioning how this role would allow her to not “interfere,” it is clear that this female disguise grants her a degree of invisibility, allowing her to do her job without causing major inconvenience to her clients.

Equipped with disguise tactics and knowledge of feminine roles, women were uniquely positioned to investigate cases that involved private life in the Victorian era. With minimal direction, Brooke was able to infiltrate domestic spaces, find answers to her questions, and solve each case quickly and efficiently. Performing roles that were gendered female enabled Loveday Brooke to be successful in her chosen career. As women were granted an increasing number of social and legal rights throughout the Victorian era and beyond, fictional success stories such as Loveday Brooke’s inspired women with a sense of agency and belief in their own independence.

Figure 1. “Detective Offices Slaters’,” Solicitors’ Journal and Reporter 39, no. 30 (May 1895): 516.

Notes

[1] Elizabeth Carolyn Miller, “Trouble with She-Dicks: Private Eyes and Public Women in The Adventures of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective,” Victorian Literature and Culture 33, no. 1 (2005): 52.

[2] The first few lady detectives appeared in the 1860s, with W. S. Hayward’s Revelations of a Lady Detective (1864) and Andrew Forrester’s The Female Detective (1864). In the late Victorian period, female detective figures gained popularity and began to appear in several periodical publications. In addition to Pirkis’s Loveday Brooke, works featuring female detectives included Clarence Rook’s “The Stir Outside the Café Royal” (1898), Beatrice Heron-Maxwell’s The Adventures of a Lady Pearlbroker (1899), and Grant Allen’s Miss Cayley’s Adventures (1899) and Hilda Wade (1899).

[3] Mary Lyndon Shanley, Feminism, Marriage, and the Law in Victorian England, 1850–1895. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 3.

[4] Adrienne Gavin, “‘C. L. Pirkis (Not ‘Miss’)’: Public Women, Private Lives, and The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Female Detective,” in Writing Women of the Fin de Siècle: Authors of Change, ed. Adrienne Gavin and Carolyn Oulton (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 140.

[5] Catherine Louisa Pirkis, The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective, ed. Michelle Slung (New York: Dover, 2020), 4.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Detective Offices (Slater’s),” Solicitor’s Journal and Reporter 33, no. 51 (October 1889): 787.

[8] “Detective Offices Slaters’,” Solicitors’ Journal and Reporter 39, no. 30 (May 1895): 516.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Pirkis, The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, 40–41.

[13] Ibid., 41.

[14] Ibid., 8.

[15] Ibid., 8–9.

[16] Ibid., 132.

[17] Ibid.