By Pacifico Lobianco

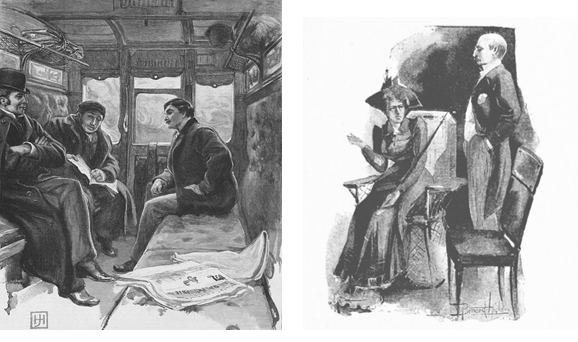

In Jacob Hood’s illustration for Grant Allen’s story “The Scallywag,” the detective, Mr. Sherrard, is depicted in an assertive, triumphant posture—shoulders back, head held high, arms and legs crossed, eyes trained on the man opposite him, lips pulled back in a subtle smirk (Figure 1). Every aspect of Sherrard’s physical appearance exudes confidence and command. Victorian readers could identify the character who was doing the detective work before reading a single word. Sherrard is respected, self-assured, and intelligent—characteristics that Hood’s illustration communicates to the viewer in bold-faced, neon lettering. Compare this to how illustrator Bernard Higham depicts Loveday Brooke in Catherine Louisa Pirkis’s “Drawn Daggers” (Figure 1). Brooke’s unassuming posture defies how we expect a detective to appear. She is slightly hunched over, her knees pointed away from Dyer, almost shrinking away from his cocky smugness. Yet her facial expression and arm gesture suggest that she takes issue with what Dyer is saying, as if she knows something he does not but is choosing to remain modest. This was, and to some extent still is, an unusual characterization for a protagonist. In Loveday Brooke, Catherine Louisa Pirkis brought a set of traditionally feminine attributes to the archetypal detective. Her stories aimed for a loftier goal than mere entertainment, speaking to broader issues of the time. In the sea of male detectives that populated the fiction sections of Victorian-era periodicals, Loveday Brooke’s stories, particularly the exemplary “Drawn Daggers,” stand out as a conduit for sharp social critique of Victorian patriarchy.

Figure 1. Left: Jacomb Hood, illustration for Grant Allen’s “The Scallywag,” Graphic 47, no. 1 (1893): 565. Right: Bernard Higham, illustration for Catherine Louisa Pirkis’s “Drawn Daggers” in The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (London: Dover, 2020), 123.

The title of Andrew Forrester’s 1864 novel, The Female Detective, demonstrates that, in the Victorian era, the very concept of a female investigator broke the conventions of detective fiction. Elizabeth Carolyn Miller points out an inherent “incongruity between late-Victorian conceptions of what women do and what detectives do.”1 But Catherine Louisa Pirkis was not content to simply redress the conventional detective—an archetype that had already become hugely popular since Arthur Conan Doyle began publishing in The Strand Magazine. Much more than simply a female Sherlock Holmes, Loveday Brooke possesses her own set of characteristics and strengths. In contrast to the bold, masculine power that is traditionally associated with heroism, Brooke is reserved and contemplative—a power of a much quieter nature. Amidst their “jangling,” Mr. Dyer allows “his temper [to] altogether [give] way” whereas Brooke always retains her composure.2 In the 1894 edition of the Pirkis’s text, Brooke is seated in fifteen of a total of nineteen illustrations, which shows she has no need to impose physical domination over others—her formidable intellect is more than enough. Pirkis furthers the theme of masculinity’s fragility through the character of Mr. Hawke. When Hawke tells Brooke and Dyer that his wife objected to his wishes to contact the police, he adds, “I hope you understand, Mr. Dyer; I do not mean to imply that I am not master in my own house.”3 Mr. Hawke’s need to assert his masculinity before another man so as not to be perceived as weak is almost humorous in comparison to Brooke’s self-assured nature. Loveday carves out her own unique, distinctly feminine territory in relation to detectives in patriarchal society.

While sexist laws severely limited Victorian women’s opportunities, Brooke succeeds time and time again regardless of the setbacks she faces. Despite the reality that “women provided over the home, while men sallied forth into the public realm,” Loveday Brooke is a professional woman by choice—unmarried and seemingly uninterested in romantic or sexual relationships.4 She is constantly underestimated and overlooked, such as when Mr. Hawke looks at her “uneasily” and Dyer has to “explain that this [is] the lady by whose aid he [hopes] to get to the bottom of the matter.”5 But instead of boisterously protesting the double standards through which she consistently gets the short end of the stick, Brooke ignores these small-time sexist transgressions. What to our modern-day perspective is a grave injustice to Brooke’s character is to her nothing but the unimportant noise of ignorance. To a woman living in Victorian-era England, these slights were commonplace.

In “Drawn Daggers,” the sexism comes not only from men but also from fellow women such as Mrs. Hawke, who says “girls . . . were always careless with their jewellery.”6 By no means does Brooke fit into any of these perceptions of women—carelessness, servitude, docility. She is resolute (“The less delay the better . . . I should like to attack the mystery at once”) confident (“Set your mind at rest”) and perceptive (“These last two daggers have not been drawn by the hand that drew the first’).7 Thus, she ignores ignorant perceptions of women—they are simply not worth her valuable time and keen attention.

In some instances, however, Brooke plays into the stereotypical expectations associated with Victorian women in order to infiltrate a place of interest without arousing suspicion. In his book David and Goliath, Malcolm Gladwell challenges the notion that underdogs are underdogs because they are at a disadvantage and questions the very nature of disadvantages to begin with. As he points out, “there are times and places where . . . the apparent disadvantage . . . turns out not to be a disadvantage at all.”8 Loveday Brooke often uses her low social standing to her own benefit, weaponizing society’s underappreciation of her capabilities to secure a favorable position for herself: in “Drawn Daggers,” for example, the role of a “lady house decorator.”9 This ability to turn a perceived disadvantage into an advantage is not only an entertaining subversion of expectations but also another means through which Pirkis weaves social commentary into her stories. In the face of blatant discrimination, Brooke uses these perceived setbacks as weapons to aid her in her work. She is all the more successful as a detective because no one suspects her of being one. Brooke possesses an uncanny ability to hide in plain sight; in a fantastically self-referential line, she says, “Sometimes . . . the explanation that is obvious is the one to be rejected, not accepted.”10

Another method Pirkis uses to reinforce the theme of Brooke’s quiet power is to retrospectively reveal that she had been figuring out more clues than she had previously let on. When Brooke first visits Mr. Hawke’s house, Pirkis tells the reader that she is suspicious of Mary’s laughter: “The girl's laugh seemed . . . utterly destitute of that echo of heart-ache that in the circumstances might have been expected.”11 But it is not until later that Pirkis reveals that Brooke was not only suspicious of Mary’s demeanor but also of her nationality—and was thus already well on her way to discovering the true facts of the case. An author’s control over what information a reader is and is not privy to is crucial to crafting mysteries that truly surprise readers. Pirkis exercises her ability to keep readers in the dark until just the right moment with fantastic effects. Her decision not to divulge what Brooke notices about how Mary pronounces the word “hush” until later in the story opens a blind spot for the reader—Loveday knows something that we do not, and we don’t know it yet.12 Pirkis is a master at toying with her readers’ expectations of omniscience that come with a third-person narrator, continuously creating gaps of knowledge between readers and the protagonist. In effect, it is not just those that Brooke interacts with in the story world who underestimate her but us as well—a whole other level of hiding in plain sight.

In the end, the mystery of “Drawn Daggers” boils down to a father trying to exercise control of his daughter and failing due to his underestimation of her resourcefulness. Here is yet another example of men overlooking the intelligence of the women around them, which beautifully mirrors what makes Brooke so effective in her profession. One has to wonder, if Brooke could have thwarted Miss Monroe’s plans, would she have done so? Or did she see a kindred spirit in Monroe—a woman who was tired of living in the shadow of men? Ultimately and paradoxically, Monroe finds her way out of that shadow by slipping further into it and taking advantage of the world’s blindness to female capability, much like Brooke. Mr. Hawke’s assumption that the mailed drawings were threats against his life, when in fact they were signals not even intended for him, speaks even further to the suggestion that a culture dominated by masculinity is so blinded by its preoccupation with violence that it remains ignorant to the acumen and value of women.

“Drawn Daggers” has a great deal to say about the quiet power that women hold in a world that values conventionally masculine traits. But on top of all its social critique and subversion of genre conventions, the story is simply a fantastically enjoyable read. Its cleverness is exemplified in the double-entendre of its title, “Drawn Daggers,” and the story breezes by at a formidable pace. And this I ask you, reader: is it simply a coincidence that the story’s title bears a striking similarity to a much more modern but no less excellent and socially conscious mystery, Knives Out? Or is this the universe aligning itself in some great repetition of literary history? The answers to these questions are perhaps mysteries fit only for a detective as capable as Loveday Brooke herself.

Notes

- Elizabeth Carolyn Miller, “Trouble with She-Dicks: Private Eyes and Public Women in ‘The Adventures of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective,’” Victorian Literature and Culture 33, no. 1 (2005): 49.

- Catherine Louisa Pirkis, The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective (New York: Dover, 2020), 123–24.

- Ibid., 128.

- Mary Lyndon Shanley, Feminism, Marriage, and the Law in Victorian England, 1850–1895, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 3.

- Pirkis, The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, 125.

- Ibid., 128.

- Ibid., 132, 138, 125.

- Malcolm Gladwell, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants (Harlow: Penguin, 2013), 44.

- Pirkis, The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, 132.

- Ibid., 123.

- Ibid., 133.

- Ibid.