Here you will find an INFORMATIVE timeline that will help us (and perhaps other students who may use COVE) flesh out the events that led to some British women gaining voting rights in 1918.

Timeline

Table of Events

| Date | Event | Created by |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Jan 1792 | Vindication of the Rights of Woman

ArticlesAnne K. Mellor, "On the Publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman" Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 10 Sep 1797 | Death of Wollstonecraft

ArticlesAnne K. Mellor, "On the Publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman" |

David Rettenmaier |

| Jan 1798 | Memoirs of the Author of a VindicationOn January 1798, publication of William Godwin’s Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. The publication of this first biography of Wollstonecraft causes a scandal and Godwin publishes a second “corrected” edition of the Memoirs in the summer of the same year. ArticlesRelated ArticlesAnne K. Mellor, "On the Publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman" |

David Rettenmaier |

| 16 Aug 1819 | Peterloo massacre

Related ArticlesJames Chandler, “On Peterloo, 16 August 1819″ Sean Grass, “On the Death of the Duke of Wellington, 14 September 1852″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| 12 May 1820 | Birth of Florence Nightingale

ArticlesLara Kriegel, “On the Death—and Life—of Florence Nightingale, August 1910″ Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 14 Jun 1839 | First Chartist Petition

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 17 Aug 1839 | Act on Custody of Infants

Related ArticlesRachel Ablow, “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act” Kelly Hager, “Chipping Away at Coverture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857″ Jill Rappoport, “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 2 May 1842 | Second Chartist Petition

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 11 Jun 1847 | Birth of Millicent FawcettBorn in Aldeburgh on the 11th of June, 1847, Millicent Fawcett would become one of the most influential voices in the British Suffrage movement. Fawcett was a political activist and leader, and wrote for several influential feminist publications. Fawcett was a dedicated suffragist, and was an important figure in the conflict between suffragettes and suffragists. She served on the Central Committee of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage, and led the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies for over 20 years. Over the course of her tenure she advocated for the education of young women, organized marches, participated in fundraisers, coordinated boycotts of political figures, and penned dozens of articles on women's issues. The first three articles are Fawcett's own writing. They predate Fawcett's involvement with NUWSS, but establish her opinions on women's rights quite effectively. The first advocates for the practical education of young middle class women. The second lays out the need for suffrage, and explains why parliament should pass a bill allowing the vote for women. The work does illustrate some of Fawcett’s suffragist tendencies as well, maintaining a focus on working with Parliament, and persuading ministers to support the cause of women. The third advocates for equal proportional representation of women in government. The final piece is not Fawcett's writing, but comes from an Oxford biography. It corroborates the person details I included above, and adds a few other salient facts.

Fawcett, Millicent G. "THE EDUCATION OF WOMEN OF THE MIDDLE AND UPPER CLASSES." Macmillan's Magazine, 1859-1907, vol. 17, no. 102, 1868, pp. 511-517. ProQuest, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/docview/5722914?accountid=13158. Fawcett, Millicent G. "THE ELECTORAL DISABILITIES OF WOMEN." Fortnightly Review, may 1865-June 1934, vol. 7, no. 41, 1870, pp. 622-632. ProQuest, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com…. Fawcett, Millicent G. "PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION." Macmillan's Magazine, 1859-1907, vol. 22, no. 131, 1870, pp. 376-382. ProQuest, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/docview/5724345?accountid=13158. Howarth, Janet. "Fawcett, Dame Millicent Garrett [née Millicent Garrett] (1847–1929)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. October, 2007. Oxford University Press, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/o… |

Elijah Boyd-Plamondon |

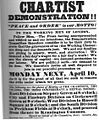

| 10 Apr 1848 | Chartist Rally, Kennington

Led by Feargus O’Connor, an estimated 25,000 Chartists meet on Kennington Common planning to march to Westminster to deliver a monster petition in favor of the six points of the People’s Charter. Police block bridges over the Thames containing the marchers south of the river, and the demonstration is broken up with some arrests and violence. However, the large scale revolt widely predicted and feared fails to materialize. ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1 Jul 1848 | Trial of Chartist leaders

The summer of 1848 witnesses violence as Chartist leaders are arrested and secret plots against the government are infiltrated. By the end of August, after the arrest of several hundred Chartists and Irish Confederates, the movement for violent uprising in England is broken. ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 14 Mar 1856 | Petition for Reform of Married Women’s Property LawOn 14 March 1856, presentation of the Petition for Reform of the Married Women’s Property Law, 1856. The petition began the joint effort by lawmakers and public women to grant married women control of their own wealth. ArticlesJill Rappoport, “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property” Related ArticlesRachel Ablow, “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act” Anne D. Wallace, “On the Deceased Wife’s Sister Controversy, 1835-1907″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| 28 Aug 1857 | Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857

ArticlesKelly Hager, “Chipping Away at Coverture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857″ Related ArticlesRachel Ablow, “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act” Jill Rappoport, “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1858 | English Woman’s Journal first published

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 9 Jul 1860 | Nightingale Home and Training School for Nurses opened

ArticlesLara Kriegel, “On the Death—and Life—of Florence Nightingale, August 1910″ Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 23 Nov 1861 | Birth of Clemence Annie HousmanClemence Annie Housman was born in Bromsgrove, England, on November 23, 1861, to Edward Housman and Sarah Jane Williams Housman. Her name was chosen because her birth day fell on Saint Clement’s Day in the liturgical calendar; notably, Clemence was fascinated by sainthood throughout her life. Clemence was the third child and oldest girl in a family of seven children, the eldest of whom was the well-known poet, A .E. Housman (1859-1936). Clemence was very close to the second youngest of her siblings, Laurence (1865-1959), with whom she lived and worked her entire life. In addition to writing novels, Clemence was a wood engraver and an activist in the feminist movement for female suffrage.(Oakely, Inseperable Siblings) |

Lorraine Kooistra |

| The middle of the month Winter 1867 | Establishment of the Manchester Society for Women's SuffrageIn the booming 1860's of Manchester, a collection of men and women saw an opportunity to mobilize local working class women by forming a society: specifically, the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage. Their environment was one where women already had a sense of independence - the burgeoning cotton fields and textile plants were employed largely by women, and it was their callused hands and weary eyes looking over some of the first suffrage petitions to be presented to Parliament. Originally founded by Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Lydia Becker, and a handful of men including Richard Pankhurst (future husband of Emmeline Pankhurst, another key member in the development of the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage and more widespread campaign groups such as the Women's Social and Political Union). While overshadowed historically by the more famous London suffrage movements, the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage survived well into the 20th century under a variety of names. Even from the beginning, their existence was crucial to the establishment of other organizations and largely encouraging working class women to join the movement, which led to the ultimate success for suffrage. Manchester was a notable hub for the textile industry, and held a large working-class population of men and women who were politically inclined. While there are few online records available, there exists a series of records from the time which briefly cover the meetings. In these, one can notice some of the names mentioned above, as well as a synopsis of the group discussions on motivation and success. A series of examinations into the MSWS' beginnings and their lesser known players by Jill Liddington, titled "Rediscovering Suffrage History", endeavours to look at the lives of contributors whose names are seldom the focus of history: Eva Gore-Booth and her partner Esther Roper, Selina Cooper, Sarah Reddish, and so on. Liddington, Jill. “Rediscovering Suffrage History.” History Workshop, no. 4, 1977, pp. 192–202 "Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage". Women's Signal, vol. 6, no. 149, 1896. |

Carly Nordaby |

| 16 Oct 1869 | Opening of Girton College at CambridgeIn 1869 the college of Girton at the University of Cambridge was founded by Emily Davies. Girton was the first women's college at Cambridge. Originally, Girton College was located at Hitchin, then shortly after opening moved to Girton where the campus remains today. Just two years later, in 1871, Henry Sidgwick opened a second college and residence for women in Cambridge which relocated to Newnham Hall and became known as Newnham College in 1875. In more recent times, the University of Cambridge opened two more women's colleges. New Hall opened in 1954 and Lucy Cavendish College opened in 1986. Although Girton paved the way for women at Cambridge, Girton began admitting men into the school in 1977, while Newnham, New Hall and Lucy Cavendish all remain strictly women's colleges. In an article titled "English and American Colleges for Women," published in 1877, the writer talks about how even though Girton was a school at the University of Cambridge the students from Girton did not receive a University degree. In another article titled "Women at the University of Cambridge," it states that women did not receive degrees or full status until 1947. Women's acceptance into college was a step forward in the suffrage movement, giving women the right to attend classes, become more independent and have more job opportunities. When women finally received full status and degree, it became and an even bigger step forward, giving women and men a more equal education. I received all of my information from articles "Women at the University of Cambridge," and "English and American Colleges for Women." All of the mapsites are women's colleges that I learned about in these articles along with Cambridge itself.

Elaine D. Trehub. "Women at the University of Cambridge." The Victorian Web, November 27, 2016, www.thevictorianweb.org/history/education/trehub/3.html "English and American Colleges for Women." New York Times (1857- 1922), Feburary 18, 1877 pp. 6. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/docview/93591529…

|

Devin Poplin |

| 9 Aug 1870 | 1870 Married Women's Property Act

This Act established limited protections for some separate property for married women, including the right to retain up to £200 of any earning or inheritance. Before this all of a woman's property owned before her marriage, as well as all acquired after the marriage, automatically became her husband's alone. Only women whose families negotiated different terms in a marriage contract were able to retain control of some portion of their property. ArticlesRachel Ablow, "On the Married Woman's Property Act, 1870" Related ArticlesKelly Hager, “Chipping Away at Coverture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857″ Jill Rappoport, “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property” Anne Wallace, “On the Deceased Wife’s Sister Controversy, 1835-1907″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| Jun 1878 | Association for the Education of Women at OxfordIn June of 1878, the Association for the Education of Women at Oxford (the A.E.W.), was formed. This association resolved issues that had been taking place since 1866, when the first few Oxford women attended lectures. These women had to have special permission to attend lectures and the lectures they attended were given by friends or relatives. A few years later, in 1873, classes were offered for women, but they were still looked at as an experiment rather than an actual Oxford education. By 1879, with the help of the A.E.W., women could have an Oxford Education. Women had the option of attending Oxford while residing in a private home or attending one of the two residental colleges. The women who attended while residing in private were attending what became known as St. Anne's college in 1942, but it was not recognized as a college until 1952. Lady Margaret Hall and Somerville were both founded in 1879 as residential colleges at Oxford. St. Hugh's women's college was founded at Oxford in 1884 and St. Hilda's women's college was founded at Oxford in 1893. Today, only Somerville and St. Hilda's remain women's colleges. Allowing women to attend classes was a step toward the right direction in the suffrage movement. Education was still very limited to women, but with time the limitations became lighter, letting women continue to move forward in the suffrage movement. I received all of my information from the articles "Women at the University of Oxford," and "Report of the Degrees for Women Syndicate." Elaine D. Trehub. "Women at the University of Oxford." The Victorian Web, November 27, 2016, www.victorianweb.org/history/education/trehub/4.html "ART.X.-1. Report of the Degrees for Women Syndicate." The Quarterly Review, vol 186, no. 372, 1897, pp. 529-551. ProQuest, https://search- proquest-com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/docview/2482551?accountid=13158 All mapsite locations placed from information given in the articles |

Devin Poplin |

| 1 Jan 1883 | 1882 Married Women's Property Act

ArticlesJill Rappoport, “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property” Anne Wallace, “On the Deceased Wife’s Sister Controversy, 1835-1907″ Related ArticlesRachel Ablow, “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 28 May 1883 to 30 May 1883 | Exhibition of the Rational Dress SocietyThe exhibition put on by the Rational Dress Society in 1883 captures the innovative spirit of the Society itself. Established in 1881, the society would put together their exhibition two years later in Prince's Hall, a public event space located on Piccadilly Street in London. This event would be the culmination of the Society's main goal: to promote and encourage dress reform among men and women, who would meet in separate groups to organize lectures, publications, and other public projects. The Society defined rational dress according to the following five qualifications: freedom of movement, absence of pressure over any part of the body, not more weight than is necessary for warmth, and both weight and warmth equally distributed, grace and beauty combined with comfort and convenience, and not departing too conspicuously from the ordinary dress of the time. A further goal of the 1883 Exhibition was to create both a supply and demand for rational dress by introducing the public and clothing trades to qualifying articles, and informing the public where such garments could be obtained. Ultimately the ideas of the Rational Dress Society did have an impact on the way clothing for both men and women was viewed. Despite this impact, it would be the natural change in fashion trends from 1900-1920 that would allow for clothing that more closely mirrored the requirements of rational dress, ending with the boyish and loosely flowing silhouettes of shorter 1920's dresses. This time period mirrored that of Woman's Suffrage campaign that ended with women obtaining the vote in 1918. Though it is rare to find publications from the Society that are within easy access, Google Books offers a free digitized version of the pamphlet from the event entitled The Exhibition of the Rational Dress Association Catalogue of Exhibits and List of Exhibitors. This primary source offers fashion plates depicting rational dress costumes shown at the exhibit, and detailed explanations of how the judges determined the winners of each category. In 2000 Ohio State University put together an exhibit of dress reform during the Victorian period that covers rational dress and beyond. This exhibit was created from Ohio State's Historic Costume and Textiles Collection, and is entitled Reforming Fashion, 1850-1900: Politics, Health, and Art. One of the best places to find opinions of and reactions to the ideas of the society were the newspapers and editorials published, such as this early article from the year the Rational Dress Society formed from Mcmillion's Magazine called Rational Dress Reform and another editorial from The Times of India just a year later entitled The Rational Dress Society |

Jennie Graham |

| 14 Aug 1885 | Criminal Law Amendment Act

Related ArticlesMary Jean Corbett, “On Crawford v. Crawford and Dilke, 1886″ Andrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 12 Feb 1886 | Crawford v. Crawford and Dilke

ArticlesMary Jean Corbett, "On Crawford v. Crawford and Dilke, 1886" |

David Rettenmaier |

| 16 Jul 1886 to 2 Jul 1886 | Crawford v. Crawford and Dilke (Queen’s Proctor intervening)

ArticlesMary Jean Corbett, "On Crawford v. Crawford and Dilke, 1886" |

David Rettenmaier |

| Oct 1887 | Launch of AtalantaUnder the editorship of L.T. Meade and Alicia A. Leith, Atalanta was a monthly girls' periodical magazine containing fiction, literary essays, and articles related to girls' issues. Atalanta's first publishing company was Hatchards (1887-1890). Other publishing companies Trischler and Co. (1890-1892), Marshall Bros (1892-1896), and Marshall Russel and Co. Ltd. (1896-1898) published later editions. L.T. Meade was among the writers in early issues, along with Frances Hodgson Burnett, H. Rider Haggard, Grant Allen, Amy Levy, John Strange Winter, and Walter Besant. In the fiction section, Atalanta offered both serialized and short stories, focusing on domestic dramas such as Mrs. Molesworth's "Neighbours" (October 1887-March 1888), and adventures such as H.E. Hamilton King's A Tale of Three Lions (October-December 1887). In the literary articles section, early publications featured Anne Thackeray on Jane Austen, Mary Ward on E.B. Browning, Charlotte Yonge on John Keble, Andrew Lang on Walter Scott. Poems were also featured in this magazine, across various themes such as sentimental, seasonal, religious, and historical subjects. |

Erni Suparti |

| Jul 1888 | London Matchgirls' StrikeIn July 1888, the London Matchgirls' Strike occurred. Related ArticlesHeidi Kaufman, “1800-1900: Inside and Outside the Nineteenth-Century East End” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1894 | "New Aspect of the Woman Question"In March 1894, Sarah Grand's “The New Aspect of the Woman Question” was published. The essay in North American Review, vol.158, no.448, March 1894, pp.270–6 has been credited with identifying the "New Woman." ArticlesMeaghan Clarke, “1894: The Year of the New Woman Art Critic” |

David Rettenmaier |

| May 1894 | Story of a Modern WomanIn May 1894, Ella Hepworth Dixon's The Story of a Modern Woman was published. It is the best-known New Woman novel and draws on Dixon's own experiences supporting herself as a journalist.

ArticlesMeaghan Clarke, “1894: The Year of the New Woman Art Critic” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 27 Jun 1894 to 12 Sep 1895 | Annie Londonderry's Bicycle Trip Around the WorldAnnie Kopchovsky (AKA Londonderry) was not the likeliest candidate to bring fame to the bicycling feats of the New Woman and make the adoption of athletic clothing acceptable for women, however, after her fifteen-month bicycle trip around the world she was cemented as a celebrity. At the time of her trip, she weighed 100lbs., stood a mere 5-foot-3, and had never ridden a bicycle before. What the public did not know was that she was a Jewish mother of three children under six, and she chose the name Londonderry to hide her recognizably Jewish name- this was large to protect her from anti-semitism and reproach for leaving her husband and children. The challenge that Annie had undertaken began when two men made a bet that a woman could not match the around the world bicycle trip of Thomas Stevens completed in 32 months. Ultimately Annie's journey was a success launching her into international fame. She would later go on a series of public speaking tours and would emphasize that giving up a skirt in favor of a bicycling costume in the first days of her trip was a large part of her success. Due to her fame, Annie became a symbol of the new woman internationally and d a model of the bicycling costume that included no cumbersome skirts. In addition to public speaking, Annie was often featured in advertisements in her bicycling costume and famous bicycle and began a writing career. She would write, "I am a journalist and a 'new woman' if that term means that I believe I can do anything a man can do." My first two sources have a close connection to Annie as they were written by Peter Zheutin whose great-grandfather was Annie's older brother Bennet. The two articles are Chasing Annie and Annie Londonderry's Extraordinary Ride. To fully understand Annie's daring in appearing in public in riding costumes it is vital to understand the historical context behind the movement. The article From Bustles to Bloomers: Exploring the Bicycles Influence on American Women's Fashion 1880-1914 written by Julia Christie-Robin, Belinda T. Orzada, and Dilia Lopez-Gydosh offers a comparative look on views of how much influence the bicycle had on women's fashion. As for primary sources, many appear in newspapers and magazines such as this article about The Short Skirt Leauge from The London Journal Ladies Supplement, and this article detailing the Aims of the Short Skirt League from the New York Times. |

Jennie Graham |

| 1897 | The Merger of the MSWS into the NUWSSTeetering at the edge of the new century, the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage found itself wanting to gain traction on a different level than before, and to discuss and share with their fellow suffragists on a more broad scale. The invitation to join (or rather, to assist in the formation) the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies along with 500 other bustling organizations was fondly received. The NUWSS stayed in high regard until some of the more active women - Emmaline Pankhurst, key member of the MSWS - split to start the Women's Social and Political Union. Regardless, the MSWS and other organizations stayed, renaming themselves the North of England Society for Women's Suffrage just to return to their original name. As such, the NUWSS continued their efforts well into the 20th century, aided by many of those original 500 or so groups that they encompassed. John, Angela V. “New Suffrage Studies.” History Workshop Journal, no. 42, 1996, pp. 223–230. Owens, Rosemary. “'Votes for Ladies, Votes for Women' Organised Labour and the Suffrage Movement, 1876-1922.” Saothar, vol. 9, 1983, pp. 32–47. |

Carly Nordaby |

| Nov 1897 | Foundation of the NUWSSIn November of 1897, two suffragist organizations, the National Central Society for Women's Suffrage and the Central Committee of the National Society for Women's Suffrage, united to form a group known as the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). This new group would be the largest organization of suffragists in Britain. The group was placed under the leadership of Millicent Fawcett, who would lead the new organization for more than twenty years, and establish them as a major political influence. The group advocated for suffrage politically, but avoided the more violent tactics of suffragettes, leading to a fracturing in the group that would produce the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). They also allowed men to be members of the organization, in contrast with more extremist groups. To advance their cause, the group engaged in campaigning against political parties that refused to address suffrage, and for those politicians who sought to address the issue. One of their early coordinated actions was a boycott of the Liberal Party in the election of 1906. Their attacks on the Liberal Party are thought to be a contributing factor in the party's replacement by the Labour Party. The NUWSS also coordinated a large march for suffrage in 1907, which was so plagued by rain that it came to be known as "the Mud March". They continued to engage in political advocacy, going so far as to raise funds to fight anti-suffrage candidates in the election of 1912. In 1913 the NUWSS organized their largest march ever, dubbed by newspapers "The Great Pilgrimage". The organization continued on a similar course until it was reorganized and renamed as the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC) in 1919. The linked sources are useful for establishing core tenets of the organization. The first is a retrospective on women's marches, which includes useful information about two of the major marches coordinated by the NUWSS. The second is a set of scans of pamphlets issued by the NUWSS. These pamphlets break down some of the major talking points of the NUWSS for Victorian readers, allowing modern readers insight into both their key talking points and how they presented those talking points. The final article is an in-depth analysis of the contributions of NUWSS to the cause of suffrage, with specific emphasis put upon their leader Millicent Fawcett. Lethbridge, Lucy. "The women’s March: How the Suffragettes Changed Britain."FT.Com, 2018. ProQuest, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com…. “NUWSS Pamphlets.” The British Library, The British Library, 3 Aug. 2017, www.bl.uk/collection-items/nuwss-pamphlets. Rubinstein, David. “Millicent Garrett Fawcett and the Meaning of Women's Emancipation, 1886-99.” Victorian Studies, vol. 34, no. 3, 1991, pp. 365–380. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3828580. |

Elijah Boyd-Plamondon |

| Sep 1898 | Closure of AtalantaUnder the editorship of A. Balfour Symington and Edwin Oliver, Atalanta maintained its educational concept and incorporated Symington's Lady Victorian Magazine (1891-1892) into it. However, the number of elaborate illustrations that surrounded many of the stories and poems began to decrease after L.T. Meade's departure as editor in 1891, possibly due to increasing publication and printing costs. The amalgamation of Atalanta and Victorian Magazine seemed to be the reason behind L.T. Meade's departure. However, she conceded in the celebrity interview in 1892 that Atalanta took up plenty of her time. She left Atalanta completely in 1893. Atalanta changed its cover design in 1894 and Edwin Oliver edited the last two volumes which featured fewer distinguished writers than was customary for the publication. Atalanta shut down completely in September 1898. |

Erni Suparti |

| 10 Oct 1903 to Summer 1917 | Formation of the Women's Social and Political UnionThe Women’ Social and Political Union was formed by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1903 in order to start protesting for women’s right to vote in England. While the main concern was to gain women access to vote, they also fought for women’s suffrage in general including more work opportunities. The women in the union were the first to be deemed Suffragettes. The title came from the term suffragist, which was peaceful protest of woman’s suffrage. The definition of a suffragette is “a woman who is fighting for a right to vote with organized protest”. However, these protests were often violent and considered anything but peaceful. The Suffragettes started fires, vandalized political buildings, were sexually assaulted and restrained by the police, as well as caused uproar during voting periods. If imprisoned, the strikes did not stop. Once in prison, the Suffragettes would often refuse to eat, and the prison would then have to force feed the women. The protesting went on for fourteen years before finally dissolving in 1917. Emmeline Pankhurst died on June 14, 1928 and did not see the fruit of her efforts. Less than a month after Pankhurst’s death the law gave women the same right to vote as men. Several suffragette-based organizations succeeded the Women’s Political and Social Union. Including the Women’s Freedom League and the East London Federation of Suffragettes. Supplemental Materials: The article by Karen Smith gives a good, brief overview of the WPSU, as well as several other related articles for more in-depth research. It also includes an image of Pankhurst and her daughter, Christabel, as well as a link to video footage of during the time of the WPSU. Lance delves into the argument of non-violence as opposed to the violent and more bold position that the Women’s Political and Social union had undertaken. He uses research on the topic to present the idea that the WPSU did indeed get women the right to vote using their tactics. This article in particular is a harder read to digest, as it involves research into the subject matter. There is a biography of Emmeline Pankhurst included, that details her life specifically as it relates the Women’s Social and political union. I included a link to a short timeline of important events during the span of the fourteen years the WPSU was active. Overall these materials are short and concise. They provide important insight into the key events and martyrs of the WPSU. Women's Political and Social Union Smith, Karen Mannes. “Women's Social and Political Union.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 17 Mar. 2017, www.britannica.com/topic/Womens-Social-and-Political-Union. Lance, Keith Curry. “Strategy Choices of the Women’s Political and Social Union, 1903-18.” Social Science Quarterly, vol. 60, no. 1, 1979, pp. 51–61. JSTOR. Kettler, Sara. “Emmeline Pankhurst.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 27 Feb. 2018, www.biography.com/people/emmeline-pankhurst-9432764. |

Samantha Nash |

| 9 Feb 1907 | The Mud MarchOn Saturday the 9th of February, 1907 a large pro-suffrage march took place. Organized by the NUWSS, over 3,000 women marched from Hyde Park Corner to the Strand. Timed to coincide with the opening of Parliament, the march was meant to drum up public sympathy for a women’s suffrage bill. The march was hindered by terrible weather conditions, with pouring rain soaking the large crowd. Public sympathy was immediate, and the sympathetic press dubbed the event the “Mud March”. Unfortunately, the march proved ineffective, as the bill never came to a vote. It did however, set a precedent of large public marches for women’s rights. The first source is a transcription of a diary from a young woman present at the Mud March. I could not find a pure scan, but the transcription is quite useful. The second source is a flyer put out by the NUWSS advertising the event. It lists the date and place, as well as some other relevant details. “Kate Frye's Suffrage Diary: The Mud March, 9 February 1907.” Woman and Her Sphere, Woman and Her Sphere, 18 Feb. 2016, womanandhersphere.com/2012/11/21/kate-fryes-suffrage-diary-the-mud-march-9-february-1907/. Mud March Poster. 9 Feb. 1907.

|

Elijah Boyd-Plamondon |

| 28 Aug 1907 | Deceased Wife's Sister's Marriage Act

ArticlesAnne Wallace, “On the Deceased Wife’s Sister Controversy, 1835-1907″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| Sep 1907 to 1961 | Women's Freedom League and The VoteIn September of 1907, 77 members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), broke off and formed the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Two of the most prominent women who helped further popularize the WFL were Teresa Billington- Greig and Charlotte Despard. The Women's Freedom League was very different from its predecessor. For starters, they were suffragists. Unlike their predecessor (WSPU) which only allowed suffragettes. The WFL was a militant organization, much like the WSPU. They were willing to break the law but did so without vandalizing property or attacking politians. WFL used forms of non-violent protests, like demonstrations or tax resistance. The WFL was a completely non-violent, passive, organization and protested aganist WSPU's violent nature. It's popularity grew rapidly and had about 60 branches througout Britain. Clarie Eustance's thesis paper references all of the 60 branches, including their location and who was in charge of each WFL branch. The organization was twice the size of WSPU. They, eventually, had the abilty to fund their own newspaper The Vote in 1909. The Vote produced weekly report of WFL's activity. These reports enlightened the readers of the organization and activities in their local communities.

My article from Maria DiCenzo explains the importance of writing in the British Suffrage Movement. Within this article it mentions the Women's Freedom League grew in popularity by having its own newpaper The Vote. It also states that Teresa Billington- Greig and Charlotte Despard were the leading writing ladies for WFL. My source is by Claire Eustance. She right all of her information in her thesis paper. It is an extensive, well informing paper that guides the reader throughout all of the WFL movements. The paper starts with the reasons for the formation of WFL, getting funding for the succesful newpaper The Vote, oppsoing the Great war, and the conclusion of the movement in 1961. Charlotte Despard Simkin, John. Spartacus Educational. Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd, https://spartacus-educational.com/Wdespard.htm Teresa Billington- Greig Simkin, John. Spartacus Education. Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd, https://spartacus-educational.com/Wbillington.htm |

Tessa Albert |

| 5 Apr 1908 to 5 Dec 1916 | H.H. Asquith as Prime MinisterH.H. Asquith was the Prime Minister of England from 1908 to 1916. Asquith was 1st earl of Oxford and Asquith. He was a member of the Liberal party and ran for Prime Minister under this party. While Asquith was Prime Minister, he faced many controversies. The Conciliation bill to give women the right to vote were brought up during his time as Prime Minister and while promising that there would be facilities for a bill such as this in Parliament, he instead favored a bill for universal manhood suffrage. These facilities that H.H. Asquith promised for a conciliation bill for women to gain the right to vote was mainly referring his support and a place politically in Parliament that would allow such a bill to be passed. There were many more controversies during Asquith’s political career such as his interactions with political extremists as well as anarchists. It is because of these many opponents of his time as Prime Minister that his political career is looked upon in a negative light. Such opponents included the suffragettes who placed a great amount of blame on Asquith for the Conciliation bills not being passed. The suffragettes had every right to place this blame on Asquith since he led them to believe that he would welcome such a bill and instead favor suffrage for all men. Asquith was also the acting Prime Minister for the beginning of World War I as well as passing the Parliament Act of 1911 which dealt with the House of Lords.

The accompanying articles show H.H. Asquith’s political stance as Prime Minister as well as a look into his time as Prime Minister. The Britannica article on Asquith offers a more general view of Asquith’s life and the dates which he served as Prime Minister as well as other events in his life. The article “The Women’s Suffrage Movement in England” shows on pages 604-605 how Asquith claimed he welcomed a women’s suffrage bill but did not favor it when it was brought up. The article entitled “H. H. Asquith and Britain's Manpower Problem, 1914–1915” by John Gordon Little shows Asquith’s time as Prime Minister and particularly how he handled his involvement in World War I. Little’s article brings up a key point about Asquith’s political career which is how over time his actions have been portrayed in a negative light. The article shows a deeper view of Asquith’s liberal views and his stance on issues such as compulsory military service. The newspaper article entitled “Mr. Asquith and the Anarchists” shows the political unrest during his time as Prime Minister. This article shows how Asquith dealt with Anarchists at this time and how Anarchists were defined at this time. The article shows that other political unrest at this time apart from the suffragette movement. However, this article is about H.H. Asquith before he was Prime Minister when he was Home Secretary. The article allows a view of another controversial event that Asquith handled during his political career.

H.H. Asquith https://www.britannica.com/biography/H-H-Asquith-1st-earl-of-Oxford-and-Asquith Robert Norman William Blake, Baron Blake. “H.H. Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 8 Sept. 2018, www.britannica.com/biography/H-H-Asquith-1st-earl-of-Oxford-and-Asquith. Women's Suffrage Movement in England https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1944309.pdf Turner, Edward Raymond. “The Women's Suffrage Movement in England.” The American Political Science Review, vol. 7, no. 4, 1913, pp. 588–609. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1944309. H. H. Asquith and Britain's Manpower Problem, 1914–1915 LITTLE, JOHN GORDON. “H. H. Asquith and Britain's Manpower Problem, 1914–1915.” History, vol. 82, no. 267, 1997, pp. 397–409. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24423466. Mr. Asquith and the Anarchists https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924057525291?urlappend=%3Bseq=730 “Mr. Asquith and the Anarchists .” The Spectator , 18 Nov. 1893.

|

Carrie Taylor |

| 21 Jul 1908 | Formation of the Women's National Anti-Suffrage LeagueThe Women's National Anti-Suffrage League was formed in 1908 at the aims to oppose women being granted the right to vote in parliamentary elections in the United Kingdom. The first meeting took place at Westminster Palace Hotel on July 21, 1908. While the League's aims were to oppose women being granted the right to vote in parliamentary elections they did support women having votes in local and municipal elections. The League has their own publication, the Antii- Suffrage Review created December the year founded and ran until it was dissolved in 1910 when it merged with the Men's National League for Opposing Women's Suffrage to form the National League of Opposing Women's Suffrage. Prominent members of the League include Mary Augusta Ward, a writer who was in charge of creating and editing the league's magazine, as the chair of the Literary Committee. Gertrude Bell as the secretary who was one of the first women to graduate from Modern History at Oxford with an honors degree. The League started with three branches. The first two were formed in Hawkenhurst in Kent and then in South Kensington in London. The third was in Dublin, Ireland. Shortly after, a Scottish branch was formed by the Duchess of Monrose in May of 1910. The League grew vigorously by December of that year 26 branches were formed and raised to 104 in 1910. In 1910, the League combined with the Men's National League for Opposing Women's Suffrage to form the National League for Opposing Women's Suffrage. This new league lasted until 1918 when it came to an end as women's suffrage had been granted. Supplemental Materials: The Spectator published a couple of columns about the League. The first article, which starts at the very bottom of the first column, discusses their views on voting and how they hold the fundamental importance that, "the spirit of sex antagonism aroused by the women's suffrage propaganda should be combated by recognition of the fact that the respective spheres of women are neither antagonistic nor identical, but complementary." In the second article, organizing secretary Annie J. Lindsay writes about the formation of the Men's Committee for Opposing Female Suffrage that was formed to support the women's league. The article by Emily Coit highlights Mary Augusta Ward and the common misconception between support for women's higher education and their right to vote. Colt's scholarly article is primarily about one of Ward's novels and her opinions on the idea's of different feminism, as well as her views of suffrage and feminism that fit into the League. The Saturday Review January 23, 1909 Mary August Ward's "Perfect Economist" "Untitled Item the National Women's Anti-Suffrage Association has..]." The Spectator, vol. 100, no. 4171, Jun 06, 1908, pp. 887. ProQuest, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com…. Lindsay, Annie J. "WOMEN'S NATIONAL ANTI-SUFFRAGE LEAGUE." Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, vol. 107, no. 2776, 1909, pp. 43. ProQuest, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com…. A MEMBER OF THE MEN'S LEAGUE FOR, WOMAN SUFFRAGE. "WOMEN'S NATIONAL ANTI-SUFFRAGE LEAGUE." Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, vol. 107, no. 2778, 1909, pp. 109-110. ProQuest, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com…. Coit, Emily. "Mary Agusta Ward's 'Perfect Economist' and the Logic of Anti- Suffragism." pp. 1213-38. ProQuest. |

Myranda Mamat |

| 12 Oct 1908 to 28 Oct 1908 | The Grille ProtestBeginning on the 12th of October in 1908, the Women's Freedom League prepared for a Special Effort Week. They began by posting on public buildings in England, calling out the goverment to remove the sex disability in the existing parliamentary franchise and demanding liberation for women. They were successful in posting their proclamations in Westminster on houses of cabinet ministers, public buildings, and letter boxes; but had not been successful at the House of Commons (Parliament). Reports were said that this was because of it being too well guarded to be reached by any woman. This of course didn't stop the WFL, it caused them to take more drastic actions. On October 28th two ladies, Helen Fox and Muriel Matters, chained themselves onto the metal screen in the Ladies' Gallery, in view of the House of Commons (Parliament). While other members spread out and littered the floor of the House of Commons with papers advocating women's suffrage. The article that I used for the Grille Protest was by Laura Mayhall. She goes into depth about the events prior to the Grille Protest and the effect that happened afterwards. This article also goes on to explain other events inspired by this successful protest. Muriel Matters Muriel Matters Society. Don Dunstan Foundation, https://murielmatterssociety.com.au/home-page/who-was-muriel-matters/. |

Tessa Albert |

| 1909 | Clemence and Laurence Housman found the Suffrage AtelierFollowing the formation of the Artists' Suffrage League, founded by renowned stained glass artist, Mary Lowndes, in 1907, which produced illustrated banners, postcards, and pamphlets used to promote the campaign for women's enfranchisement in Britain and North America, Clemence and Laurence Housman established their own Suffrage Atelier in 1909. Its practices took place at artists' homes, before the Housman siblings offered the site of their small home, Pembroke Cottage in Kensington, as its headquarters. Though the location of its headquarters would change three more times within its five operational years, the collective vision of the Atelier remained the same: it was to act as an arts and crafts society which worked towards the enfranchisement of women, with an additional effort to encourage artists to forward the women's movement by means of pictorial publications. (VADS, "The Women's Library: Suffrage Banners") In contrast with its predecessor, the Artists' Suffrage League, the Housmans' Suffrage Atelier encouraged non-professional visual artists and enthusiasts to submit their work to the cause in addition to professional artists, and also offered a small percentage of the sold works' profits as compensation. The Atelier also contrasted with its associates, the Women's Freedom League (1907-61) and the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) (1903-17), stylistically, by means of the colours its members chose to use in the creation of its feminist propaganda. While the other organizations used white, green, and purple, which are commonly known as the defining colours of the suffrage movement, the Atelier used a broader range of hues, as depicted in one of its banners (at left), wherein blue, black, and gold are used. Clemence led the team, and also lent her talents as an embroiderer, illustrator, and wood engraver to the Atelier, often spending entire days sitting on a floor cushion, doing her needlework or engraving in order to benefit the cause. Laurence designed a number of the Atelier's banners. As Clemence Housman was a respected member of the WSPU, much of the Atelier's work could be found for purchase within its store chains and also within the pages of its national newspaper. The Atelier held printmaking workshops and competitions in addition to the numerous exhibitions, political rallies and processions its members would regularly attend and circulate their artwork at, while also allowing for new and meaningful relationships to be forged between women as they worked collaboratively to aid a feminist cause which married the artistic with the political. The feminist nature of the workshop's artistic operations also subverted the common belief that embroidery and needlework reinforced women's domestic place within the home. The Suffrage Atelier ran from 1909-14. (Morton, "Changing Spaces: Art, Politics, and Identity in the Home Studios of the Suffrage Atelier") |

Alex Heath |

| 8 Oct 1909 | The Dangers of Forcible FeedingOn October 8th 1909, an article called "The Dangers of Forcible Feeding" was published in the News Paper Votes For Women. The newspaper itself was founded in October 1907, it was the offical news paper for the Women's Social and Political Union (WPSU). The news paper was a monthly issue with weekly additions to keep up-to-date. In the article "The Dangers of Forcible Feeding" was published as a way for people to be informed about the cruelty of forced feeding. The article also contained signatures from men and women who pratice madicine to have someone intervene and prevent anymore forced feedings from happening. The image shown is just one of the many ways women in the suffragette movement were forceably fed, another way they were fed was by having the woman held down to the ground while the tube was inserted through the nose and down the throat. This image in particular was used to show the people as well as goverment officals how suffragettes were being treated while in the care of the prison's docotrs and care takers. The main goal was to have people vote to stop the force feedings done to suffragette members. The Dangers of Forcible Feeding https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=IMJZBBnUFLgC&dat=19091008&prints… |

Austin Feathers |

| 9 Oct 1909 | Summonses For Forcible FeedingThis article recounts the second half of a trial with the Homesecurity, govenor, and and doctor of Winson Green Gaol. The recounting goes on over a few days. This was done with the argument that the force feedings were actually assualt. The suffragettes noted how they were pinned down or held down in the chair, and that they felt violated after the procedure was finished and returned to their rooms. They said that the feedings happened twice a day, once in the the morning and the other was in the evening. The suffragettes mentioned in court how sometimes instead of a tube being forced down their throat, the doctor pryed their mouths open and pored liquid and meat extract down their throats with a spoon. Also, anyone doctor or nurse who enacted the feeding were criminally liable. There is also a testimoney from a suffragette who was forcibly fed by the doctor. In the recounting, the suffragette recounts some of the damages that force feeding had on her body. It is mentioned the some of the women have lost a great amount of weight, 13 pound to be exact, over the couse of the forced feedings, as well as change in facial detail for example pale complection and thinning of the hair, some suffragettes noted that from the tube being forced down their throats that at the time being they are sufferng from swollen throats and are to weak to talk much.. The ruling from the judge in the case, was that the doctor as well as the police officer were found innocent, becuase the feedings were being done inside of the law and he could not find anything illegal about the actions that took place. The image shown is of a suffragette who is standing up to go and testify on her treatment while in the prison. She is still in pain from having the force feedings enacted on her, she notes how a tube was forced down her throat and a mixture of liquid and meat extract was poured down the tube. She could not talk much becuase of how badly injured her throat was due to the tube. https://news.google.com/newspapersnid=IMJZBBnUFLgC&dat=19091015&printse… |

Austin Feathers |

| 15 Oct 1909 | Statement by Mrs. Mary LeighThis article is from the "Votes for Women" newspaper. This was posted in their October 15th edition, the article is a statement by Mrs. Mary Leigh to her Solicitor. The article is about Mary Leigh's experience at Winston Green Gaol with forced feeding since September 22nd to October 2nd. She explains what happened durring her first forced feeding, with how she was informed anout how she was going to be forced feed along with all of the different ways that she was forced fed. The article also includes her argument to get a fellow suffragette released because she had a weak heart and then how after every force feeding they checked her heart. |

Austin Feathers |

| circa. The end of the month Autumn 1909 to circa. 1 Dec 1918 | Women's Tax Resistance LeagueThe Women's Tax Resistance League was established in 22nd October 1909, with the express purpose of resisting paying taxes to protest inequality towards women; the express form of protest was in not paying unfair and unnecessary taxes to not give to a government that discriminated against women. Louisa Garrett Anderson held the first meeting at her flat in Harley Street and members of the Women's Freedom League attended as well. The WTRL used to be part of the WFL but split off from the other organization due to differences in how to protest and not wanting to be militant at all. The objectives of the league were to assist women with taxes, protesting via not paying taxes (such as income taxes and license taxes put upon women, for their dogs, use of vehicles, use of guns), holding public meetings and distributing propaganda. They were mostly professional women such as teachers, etc, who joined. John Hampden was the man who inspired them to protest because he used his ship and resisted paying taxes, so that is why they used a ship to represent themselves. Some members were Ethel Ayres Purdie, a committee member and tax adviser who advised the women on their taxes and designed ads which attracted attention to the group and their purposes. The other one was Margaret Kineton-Parkes, who went to conferences and petitioned for the group to be more widely known. Other members were The women protesting used the government seizing their goods as public displays for their cause. Members of the league often gave back the possessions they'd lost to the women who lost their homes protesting unfair taxes. When women protested, their properties were taken from them or else they were placed in prison. The group also had a resistance against the census of 1911 and took part in other activities as well. The WTRL suspended meetings when World War I broke out-and subsequently resumed them in 1916 when they attended the Consultative Committee of Constitutional Women's Suffrage. After this, one more meeting was held in 1918 after women got the right to vote-this meeting was held to officially end the organization. Some of the links I used were https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=17nHZu2ZbU0 which explores how they were formed, for what purpose and when they broke up. The Youtube video does a good job in illuminating their history and their story, with good images and history. The second link I used is here: British Periodical that held an article mentioning WTRL and the website lists different sections of newspaper articles and periodicals from Britain that is easy and navigate and easy to use. Images: This one came from Wikipedia and is the official badge of the WTRL. Inspired by John Hampden, who was a man who rebelled over being forced to pay his ship taxes and thus opposed the king and faced criminal charges over it, and thus they were inspired by seeing a man like that influence their group and were honored to have a ship serve as a reminder of what they were fighting for. MLA https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=17nHZu2ZbU0 accessed 11/7/18, , https://www.kent.ac.uk/sspssr/womenshistorykent/themes/suffrage/wtrl.html, Women of Tunbridge Hills History Project https://search.proquest.com/britishperiodicals/docview/3939755/B6FC722122894B72PQ/1?accountid=13158 Louisa Garrett Anderson Info, Simkin, John, accessed 11/25/18 I |

Lois Fagan |

| 1910 to 1913 | Emmeline Pankhurst and suffragette involvement in the Conciliation BillsEmmeline Pankhurst was the owner of a women’s shop called Emerson’s. Emmeline Goulden married Dr. R. M. Pankhurst who was also an advocate for the rights of women which furthered her interest in women’s rights. Emmeline Pankhurst established The Women’s Social and Political Union in 1903. The Women’s Social and Political Union was a militant organization in the years before World War I with women smashing store windows, going to parliament meetings to shout, “Votes for women” and other political protests. This is interesting in relation to Pankhurst because she advocated the smashing of store windows while she was a shop owner. Pankhurst owning a shop also put her in a more progressive position than many women at this time because she owned her own business. In 1910 The Women’s Social and Political Union started protesting the rejection of the conciliation bill and H.H. Asquith’s promise that a bill for women’s right to vote being facilitated. The protests included many tactics such as using acid to burn suffragette slogans into the golf courses that member of the Liberal party, which H.H. Asquith belonged to, played on. They also cut telephone and telegraph wires, set fire to letters in public postboxes and on one occasion set off a bomb in Llyod George’s partly built house. Lloyd Geroge was in opposition to the Liberal Party and was considered radicial in his opposition to the Liberal Party. One of their protests in of 1910 became known as “Black Friday” when 300 women tried to enter Parliament to stand up for their rights and a riot followed. Winston Churchill was the home secretary at this time and showed the government’s wrath with the extreme police brutality on “Black Friday.” The book review entitled “A Conservative Revolutionary: Emmeline Pankhurst (1857-1928)” gives a detailed account of how Emmeline Pankhurst was described in June Purvis’s biography of her. Purvis describes Pankhurst in very masculine terms such as “A Reel of Steel” while other articles describe her as the exact ideal of beauty in England in Pankhurst’s time. This article is important because it gives background on Emmeline Pankhurst and discusses the images other articles made of Emmeline Pankhurst. This article discusses her life and what she was really like behind all the media images created about her. The article “The Most Prominent Suffragette” gives a look at the biography written by Purvis and talks about Pankhurst’s life in addition to the obstacles she faced in fighting for women’s rights. In this article, she points out some important flaws in the biography of Pankhurst such as a lack of information on her views of race. The article “Model Citizens and Millenarian Subjects: Vorticism, Suffrage, and London's Great Unrest” is about representation of suffragettes but shows a more In-depth view of the protests that Emmeline Pankhurst’s organization The Women’s Social and Political Union carried out in 1910. The article on page five goes into detail about the types of protests that the suffragettes used to gain attention for their cause. The article “The 1910s: ‘We have sanitised our history of suffragettes’” is also about the representation of suffragettes but gives a look into the suffragette protest that became known as “Black Friday” which was in the attempt to get the Conciliation bill passed.

A Conservative Revolutionary: Emmeline Pankhurst (1857-1928) ROLLYSON, CARL. “A CONSERVATIVE REVOLUTIONARY: EMMELINE PANKHURST (1857-1928).” The Virginia Quarterly Review, vol. 79, no. 2, 2003, pp. 325–334. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26440996. The Most Prominent Suffragette Winslow, Barbara. “The Most Prominent Suffragette.” The Women's Review of Books, vol. 20, no. 8, 2003, pp. 13–14. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4024138. Model Citizens and Millenarian Subjects: Vorticism, Suffrage, and London's Great Unrest Richards, Jill. “Model Citizens and Millenarian Subjects: Vorticism, Suffrage, and London's Great Unrest.” Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 37, no. 3, 2014, pp. 1–17. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/jmodelite.37.3.1. The 1910s: ‘We have sanitised our history of suffragettes https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/feb/06/1910s-suffragettes-suffragists-fern-riddell Riddell, Fern. “The 1910s: 'We Have Sanitised Our History of the Suffragettes'.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 6 Feb. 2018, www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/feb/06/1910s-suffragettes-suffrag…. Lloyd George https://www.britannica.com/biography/David-Lloyd-George Robert Norman William Blake, Baron Blake. “David Lloyd George.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 19 Mar. 2018, www.britannica.com/biography/David-Lloyd-George.

|

Carrie Taylor |

| 1910 to 1912 | Conciliation BillsThe Conciliation Bill was a bill that would give women who owned property as well as some married women the right to vote in England. If the bill had been passed it would have extended the right to vote to an estimated 1,000,00 women. The bill was brought up to the House of Commons on three separate occasions in 1910, 1911 and 1912. The bill gained a lot of support from women’s suffrage movements such as the Women’s Social and Political Union. The bill was rejected each year it was brought up to the House of Commons and in 1913 it was decided by constitutional suffragists that the bill would need to be rewritten completely to fit with the standards that the government was forcing on the bill for it to be passed. After it was decided that the bill would need to be completely rewritten the supporters of the Conciliation bills were left back where they started with no bill at all and no apparent hope for women to gain the right to vote. The bills were rejected in favor of the universal manhood suffrage bill. Many of the suffragettes and women’s suffrage supporters blamed the Prime Minister at the time H.H. Asquith for the rejection of the bills because he promised if re-elected he would give “facilities in the new Parliament for the passing of a Women’s Suffrage Bill.” The articles related to the Conciliation bills are mainly news articles from the times the bill was proposed to the House of Commons. The journal article “The Women’s Suffrage Movement in England” shows the obstacles faced by suffragists and suffragettes while trying to get the bill passed as well as why the bill was not passed. In this article from pages 604-607, the conciliation bill is discussed from the conception of the bill to the bill’s eventual defeat. The article also discusses H.H. Asquith’s role in the bill as well as his promise to help the bill in parliament that he did not keep. The House of Commons favoring a universal manhood suffrage bill is also discussed in this article. The newspaper article Great Britain. There is again a Woman's Suffrage Bill before Parliament shows the actions taken by the suffragettes at the time as well as defining who the bill would give suffrage to. The newspaper article also addresses the Prime Minister at the time H.H. Asquith’s promise during his campaign as well as the journal article. This article shows the attitude at the time towards this bill with the portion talking about the support of the bill from the suffragettes as well as the language used to talk about the last conciliation bill that was rejected. The newspaper article from the New York Times The English Conciliation Bill offers a unique look at the bill since it is from an American newspaper. The article is a letter to the editor offering a view that women in England needed to rally more for the bill since the percentage of women supporting the bill had dropped. This article also offers a great definition of what the bill was meant to do and who it was meant to give suffrage to, which was mainly women who held property. The other New York Times article entitled Commons Refuse the Vote to Women offers a look at when the bill was rejected in 1912 for the last time. The article shows the statistics of how many voted in favor of the bill and how many opposed the bill. The article also offers a look at how Parliament in 1912 tried to justify why the bill was rejected by blaming Irish nationalists.

Great Britain. There is again a Woman's Suffrage Bill before Parliament Margaret Heitland : Great Britain. There is again a Woman's Suffrage Bill before Parliament . . .; International women's news. Vol. 5, Iss. 7 (1911) pg. 52 The English Conciliation Bill https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1911/03/02/104779920.pdf Gardiner, Margaret Doane. “The English Conciliation Bill.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 2 Mar. 1911, www.nytimes.com/1911/03/02/archives/the-english-conciliation-bill.html. Commons Refuse the Vote to Women https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1912/03/29/100357878.pdf Marconi Transatlantic Wireless Telegraph to The New York Times. “COMMONS REFUSE THE VOTE TO WOMEN; Conciliation Bill Defeated by 222 to 208 Votes -- Ministers on Opposite Sides.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 Mar. 1912, www.nytimes.com/1912/03/29/archives/commons-refuse-the-vote-to-women-co… The Women's Suffrage Movement in England https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1944309.pdf Turner, Edward Raymond. “The Women's Suffrage Movement in England.” The American Political Science Review, vol. 7, no. 4, 1913, pp. 588–609. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1944309. |

Carrie Taylor |

| 1911 | Universal Manhood Suffrage BillUniversal manhood suffrage was introduced in Parliament instead of the Conciliation bill giving women the right to vote in 1911. This bill would allow all men to vote to remove the prior restrictions such as being required to be a landowner. Parliament and the Prime Minister at this time H.H. Asquith’s decision to favor this bill and not the conciliation bill made many people angry. Suffragettes were the most outspoken in opposition to this bill as they were working to get women who owned property the right to vote and were rejected in favor of manhood suffrage. This was viewed as a betrayal to the suffragettes because H.H. Asquith said while running for re-election as Prime Minister that he would facilitate a Conciliation bill that gives women the right to vote in Parliament. H.H. Asquith after announcing the universal manhood suffrage bill said he still would facilitate a conciliation bill, but it did not pacify the suffragettes. The article “The Englishwoman: Militancy and the Reform Bill” talks about the universal manhood suffrage bill on page 242 and describes the bill and the trouble associated with the bill. The suffragettes saw as well as many other people that with this bill being passed it was unlikely that a Conciliation bill would be passed. The newspaper article “Great Britain. At this crucial period in the fight for Woman's Suffrage” shows the early stages in getting the universal manhood suffrage bill passed. This article shows that the Labor party was not in favor of the universal manhood suffrage bill and talks about the Women’s Social and Political Union’s involvement. The article “The Women’s Suffrage Movement in England” on page 606 gives a more detailed look at when the bill was introduced and the reaction from suffragettes to the bill as well as the attitude about H.H. Asquith after the introduction of the bill. Great Britain. At this crucial period in the fight for Woman's Suffrage The Secretary of the W S P U : Great Britain. At this crucial period in the fight for Woman's Suffrage...; International women's news. Vol. 6, Iss. 6 (1912) pg. 52-53 The Englishwoman: Militancy and the Reform Bill P Whitwell Wilson : Militancy and the Reform Bill; The Englishwoman. Vol. 15, Iss. 45 (1912) pg. 242 The Women's Suffrage Movement in England https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1944309.pdf Dilke, Emilia F. S. “Woman Suffrage in England.” The North American Review, vol. 164, no. 483, 1897, pp. 151–159. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25150939. |

Carrie Taylor |

| 17 Jun 1911 | Women's Suffrage Procession at Coronation of George VIn this famous suffrage procession marking the Coronation of George V, the banner designed by Laurence and created by Clemence in 1908 for the Kensington Women’s Social and Political Union made one of its numerous appearances in public parades. The striking banner, “From Prison to Citizenship,” features the suffragist colours, depicting a white figure on a purple background, decorated with green vines. The design was so popular it was also incorporated into a postcard for wider distribution. Clemence personally enacted this slogan later in 1911, when she spent a week in Holloway Prison for refusing to pay property taxes until she was granted full citizenship. Her act of civil disobedience did not grant her full citizenship, but it did add strength to the movement. Some women got the vote in 1918, but it took until 1928 for universal female suffrage to be achieved in the United Kingdom (Liddington, Vanishing). |

Lorraine Kooistra |

| 29 Sep 1911 to 6 Oct 1911 | Clemence Housman imprisoned for tax resistanceOn Friday, September 29th, 1911, Clemence Housman was arrested for purposefully resisting the payment of taxes. This action was born out of her active participation and creative leadership within suffrage movements. Both Clemence and Laurence, who lived in Kensington, were geographically central to the suffrage movements, and loaned their creative skills to the Women’s Freedom League, through their efforts at their Suffrage Atelier. Clemence, with her considerable sewing skills, was the “chief banner-maker of the suffrage movement,” and collaborated with Laurence on the famous banner bearing the slogan “From Prison to Citizenship.” Clemence’s own tax resistance was part of a larger movement of the Women’s Tax Resistance League (WTRL), which used strategies of civil disobedience to campaign for women’s suffrage. Clemence, who lived with her brother, did not legally have any property on which to pay taxes, so she rented out a house in the rural community of Swanage, where she eluded the census of 2 April 1911. An entry in her diary at this time was “No Vote No Census Clemence Housman.” Along with other WTRL members, Clemence refused to pay taxes on her rental property in 1911, and was admonished in a government letter in July, to which she replied that she was on holiday and unable to pay taxes. Finally, on September 29th, the tax authorities caught up with her, and she was arrested from her Kensington house. The suffrage community gathered at her house to show support, and Laurence himself escorted her to Holloway Prison. Immediately after her incarceration, Clemence petitioned the home office explaining her reason for alluding taxes, that she felt that she had “personally fulfilled a duty, moral, social and constitutional, by refusing to pay petty taxes into irresponsible hands.” At this time, Laurence commented to the press: "when they give her her freedom, she will do it again until representation has been granted." Clemence was released from Holloway quietly on 6 October, an event that attracted considerable press because of the position of her and her family within the artistic and suffrage communities. A special cable to the New York Times called Clemence a "Suffragette Martyr" (Liddington, Vanishing for the Vote; "Suffragette Martyr," The New York Times). |

Emily Hunsberger |

| 28 Feb 1912 | Violet Markham's Speech at Royal Albert HallOn February 28, 1912, Violet Markham gave a speech where she explained how the women who were claiming the parliamentary suffrage were ignoring other opportunities that the law has already given them. As a member of the Women's National Anti- Suffrage Leauge member Markham addressed an anti-suffrage meeting at the Royal Albert Hall where she gave a speech about the women's suffrage movement claiming that "men and women are different- not similar- beings." The Women's National Anti-Suffrage League were opposed to voting for Parliment but supported women voting in local and municipal elections. Although against suffrage, Violet Markham was a very independent woman. She grew up as a wealthy daughter of an engineering company out of Chesterfield and had inherited enough wealth from to live independently and buy her own house in London. Throughout her life, Markham was known as being a social reformer and held many chair positions on educational boards and well as poverty and unemployment organizations. Supplemental Material: The Spectator wrote a column on Markham's speech that covered the issue of protest amongst both suffrage and anti-suffrage parties. It also mentions Mr. Harcourt's speech at about pro-suffrage and anti-suffrage and the split it has made in the cabinet. The article by Julia Bush touches on all forms of anti-suffragism in Britain and includes many of the women who were committed to opposing the parliamentary franchise. Bush writes about the famous Albert Hall speech given by Markham and many of her other accomplishments with the Women's National Anti- Suffrage Leauge. The main part of this article focuses on the Forward Policy which focuses upon the development of a positive and constructive anti-suffragism by league members such as Mary Ward and how Markham's speech had helped push the ideas forward. British Women's Anti- Suffragism and the Forward Policy, 1908-14 |

Myranda Mamat |

| 18 Summer 1913 to 26 Summer 1913 | The Great PilgrimageThe Great Pilgrimage was the largest march organized by the NUWSS. Taking place over several weeks in the Summer of 1913, the march was the culmination of the NUWSS efforts at organized marches and rallies. Over 50,000 women from across England and Wales marched across the countryside to London. Once they arrived, they gathered in Hyde Park for a rally. The march took weeks to finish, and was covered extensively by the press. The march was praised for its polished execution and lack of violence, and garnered extensive public sympathy. While there was negative press, the event was covered more favorably than might have been expected. The first source is an overview of women's marches, with a particular focus on The Great Pilgrimage and the Mud March. The second is an overview of the day, which includes several useful scanned documents, and a full list of societies and personnel. Lethbridge, Lucy. "The Women’s March: How the Suffragettes Changed Britain."FT.Com, 2018. ProQuest, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com…. “Women's Suffrage Procession through Cambridge of Sat 19th July 1913.” Lost Cambridge, 1 Dec. 2017, lostcambridge.wordpress.com/2017/12/01/womens-suffrage-procession-through-cambridge-of-sat-19th-july-1913/. |

Elijah Boyd-Plamondon |