The site for all your interesting events from the locales you will investigate.

Timeline

Table of Events

| Date | Event | Created by |

|---|---|---|

| 1600 to 1700 | 18th Century: The Rise of Kensington Palace as a Royal ResidenceIn the 18th century, Kensington Palace evolved into a significant royal residence, shaping the identity of what is now the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Originally acquired by William III and Mary II in the late 1600s, the palace gained prominence during the early 1700s as it became the favored home of Queen Anne, King George I, and King George II. The 1700s saw architectural expansions, such as Sir Christopher Wren's extensions and Queen Caroline's redesign of the gardens, which helped transform the site into a symbol of British monarchy and statecraft. This development had a noticeable impact on the local population. With the presence of the royal court, aristocrats and members of high society began to build homes nearby, increasing the borough's wealth and prestige. The growth of this elite community also required an expansion of services, prompting migration of working-class individuals to the area to work as domestic staff, tradespeople, and servants. Though not wealthy themselves, these residents formed an essential backbone of the borough’s economy and social structure. The palace’s increasing political and cultural importance not only elevated the borough's profile but also marked a shift in royal power from central London to the western suburbs. This movement helped lay the groundwork for Kensington’s status as a high-profile residential and cultural area. "Kensington Palace." Historic Royal Palaces, www.hrp.org.uk/kensington-palace/. Accessed 21 Apr. 2025. |

Hailey Burchfield |

| 1700 to 1760 | Neglect of Windsor Castle and It's RenovationThroughout the 18th Century, during the reigns of George I and George II, Windsor Castle experienced varying times of un-use and neglect. Both monarchs preferred other homes such as St. James’s, Kensington, or Hampton Court. These locations were more central to the city of London, as Windsor is more far removed (around 20 miles or so outside of the city). By staying close to the capital city of London, these monarchs claimed they were able to be more in tune with the latest social and political life of the city than they could have been at Windsor Castle. The early 1700s was a particularly important time in London’s history as The Bank of England was just founded in 1694. Obviously, from long periods of little to no occupation from the royal family, Windsor Castle experienced some neglect and disrepair, as well as the apartments generally falling out of the trends of the time. Some of the apartments were offered to friends of the Crown, but it was largely un-used. Additionally, during this time, the castle was opened for wealthy tourists who wanted to tour the inside of the castle, until eventually the general public was also able to take tours of the grounds and property. However, following the ascension of George III in 1760, this narrative changed. George III much rather preferred Windsor to any of the properties in London. He did some major renovations to the castle to help repair some of the aforementioned disrepair and outdated elements. He also purchased properties around Windsor such as the Royal Lodge in Windsor Great Park, which became a hunting lodge and country retreat for the royal family. George III would often go out of his way to remain in Windsor as much as possible, and his admiration for the town was reflected back at him. During his reign at Windsor, the children of the town were often seen playing on the grounds of the castle and King George III and his wife were often seen around the town doing their shopping. His love of Windsor set the scene for Queen Victoria to use it as her primary residence in the following century.

Ditchfield, William Page. “Windsor Castle: History | British History Online.” Www.british-History.ac.uk, 1923, www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/berks/vol3/pp5-29. Accessed 23 Apr. 2025. McQuillian, Kate. “The Legacy of King George III - College of St George.” College of St George, 29 Jan. 2020, www.stgeorges-windsor.org/image_of_the_month/the-legacy-of-king-george-…. Accessed 24 Apr. 2025. Royal Collection Trust. “Visiting Windsor Castle through the Centuries.” Www.rct.uk, www.rct.uk/visit/windsor-castle/visiting-windsor-castle-through-the-cen…. Accessed 23 Apr. 2025. Zatz, Sydney. “Windsor Castle: Its Origins as a Royal Residence - Royal Central.” Royal Central, 12 Mar. 2022, royalcentral.co.uk/features/windsor-castle-its-origins-as-a-royal-residence-173728/. Accessed 23 Apr. 2025. |

Noah Meckes |

| 1703 | The building of Buckingham PalaceBuckingham Palace is the home and administrative headquarters of Britain's monarchs, originally built as a large townhouse for a duke in 1703. Since then, it has had an expansive history, where it turned from essentially a country home, to a 700-room palace. It was built by the Duke of Buckingham, and later purchased by King George the 3rd in 1762, for 28000 pounds. It was then given as a gift to Queen Charlotte in 1775.

The building was then renovated by George the Fourth, who never ended up living there. The first monarch who lived there was Queen Victoria. Even then it was not used as a proper, stable home and seat for the royalty, as it fell into disrepair. As time went on it was only used for ceremonies and balls. George the fifth and Queen Mary lived there in the 20th century, making it much more home-like.

It was also a victim of The Blitz, however it was used to celebrate the end of World War Two with the royal family and Winston Churchill.

At its current state it is home to over 700 rooms, including a cinema, swimming pool, post office, chapel, and even a surgery room. The upkeep and running of a building this size, along with its administrative purposes, requires over 600 employees. There are 760 windows. There are 350 clocks requiring two full-time clockmakers. There is a full-time fendersmith employed (clean and maintains fireplaces) - and there are 300 chimneys. The garden at Buckingham palace is 42 acres. That is about 31.8 football fields. This garden is home to a mulberry tree over 400 years old (1567). There is a museum on the grounds, and there is said to be over 10 million euros worth of art and antiques - not all of it on display. Sacyr. “Buckingham Palace's Hidden Secrets.” Sacyr Blog, 20 Oct. 2022, https://www.sacyr.com/en/-/los-secretos-que-esconde-el-palacio-de-bucki…;

Vickers, Hugh. “The History of Buckingham Palace.” British Heritage, British Heritage, 13 Mar. 2023, https://britishheritage.com/history/history-buckingham-palace.

|

Kierra Weyandt |

| 1710 | St. Paul's Cathedral and It's Audience

Because of The Great Fire in 1666 that destroyed approximately 13,500 houses and Old St. Paul’s Cathedral, and other priceless architecture, the 1700s were marked as a period of reconstruction and modernization of the previous medieval city. While the emphasis was placed on rebuilding the city, the displacement and new homelessness of London’s population were severe. Considering the fire occurred pre-insurance, a specific, The Fire Court, was designated for property disputes and financial hardships. The Great Fire led to today’s insurance industry. The New St. Paul’s Cathedral was constructed by architect Christopher Wren and consultations with the church. Today, it consists of baroque ornamentation with neo-gothic features such as Portland stone. The church reflected the shift from Catholicism to Protestantism. The church was completed in 1710. Wren oversaw the reconstruction of fifty-two churches In London, twenty-five of which have survived time. Inside the church there is a miniature and layout of Wren’s original design for the church as well as Wren’s gravestone which reads ‘ if you seek his memorial, look about you’. Wren experienced financial constraints for the rebuilding of the cathedral. Within the church, a Nigerian installation titled Still Standing by Victor Ehikhamenor rests next to a plaque that commemorates a British admiral that led the 1897 expedition to gather the African artifacts from the Benin Empire. Current discussion around the return of symbolic and stolen objects is debated, as the British have frequently sought out to control, displace, and capture artifacts from cultures/countries. Within the crypts of St. Paul, colonialism figureheads of the British Empire are housed. Including Horatio Nelson who frequented British occupied Honduras, Nicaragua, and Caicos Islands. This erasure and blatant celebration of the horrors of colonialism is, personally, one of the most striking features the cathedral has to offer. What privilege it must have been to pillage sacred symbols for display in St. Paul’s, a church that took thirty years to finish construction outliving several generations of children as 74% of children died before the age of five in London during the 1700s(“The History…).St. Paul’s Cathedral remains a social and political hub for reformers to ideally create a greater London. Davies, Sian. “Five Ways the Great Fire Changed London.” BBC News, BBC, 22 July 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-36774166. Jhala, Kabir. “Nigerian Installation in London's St Paul's Cathedral Provokes Debate around Restitution and Colonial Monuments.” The Art Newspaper - International Art News and Events, The Art Newspaper - International Art News and Events, 18 Feb. 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/02/17/nigerian-installation-in-lon…. “The History of London.” London's History, https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/in-brief-early-georgian-london/3/.

|

Hollie Keller |

| Sep 1718 | The Construction of St Alfege ChurchDuring the Viking raids in England, one of the key positions that they would land on was in Greenwich. The army of the Danish was planted in Greenwich of well over 3 years and used it as a key position in raiding places like Kent and Canterbury. While raiding the British in Canterbury, the Vikings were able to capture Archbishop Alhpege and hold him for ransom against the nobility of England. However, Alphege refused to have his bounty paid and he was butchered by the Danish for his acts against them. Alphege became a martyr and was given sainthood in April of 1012. Many years later, the influence of the Catholics died down with the Protestant Reformation and several attacks against the Catholics in England. Before the death of Queen Anne in 1814, she passed a series of Acts that allowed for the construction of several Catholic churches and subsequently the Church of St. Alfege (Daniell). During the reign of Queen Anne and on, there was a certain level of Catholic influence that was present in the communities. Despite the history of London having a strong Protestant influence, the Queen Anne Acts proved that there was a sect of Catholics still in London as of the 18th century. Additionally, the church was built by Nicholas Hawksmoor by 1714, but it wouldn’t be consecrated until 1718. The church has the typical construction of most churches in England, but the rich history of the area and the name of the church is what make it unique. The church was even used during WWII as a bomb shelter that helped defend those in air raids. The church suffered internal damages from the bombing raids but still stands to this day. As of 1982, the church is no longer used for services and stands as a historical monument.

Sources: Daniell, Alfred Ernest, and Alexander Ansted. London Riverside Churches ... with 84 Illustrations by Alexander Ansted. Archibald Constable & Co., 1897. Ross, David. “Canterbury, St Alphege Church - History, Travel, and Accommodation Information.” Britain Express, https://www.britainexpress.com/attractions.htm?attraction=3372. |

Aidan Pellegrino |

| 1729 to 1730 | St. Anne's Church LimehouseSt. Anne's Limehouse is a church in the Church of England built between 1714-1727 under the direction of an Act of parliament in 1711 (St. Anne's Limehouse). It was created as “St. Anne’s Limehouse” by the Limehouse Parish Act (1729) and officially consecrated in 1730 (Cryer). The idea was to serve a growing population of East London. Queen Anne, who had ordered the building of this church, decreed that the captains could register events that happened at sea since the church was not far from the River Thames. This same reason (being close to the Thames) is why the clocktower is the highest in London. Additionally, thanks to the special status afforded to this church as a registry of happenings on naval ships, it can fly the White Ensign of the British Navy all year round, which is a formal flag consisting of the Union Jack in an upper left corner and the St. George's cross (Munks). (This flag has a long history going back to the Tudors, which used to more colorful, but the colors changed to red, white, and blue. The White Ensign now looks the same as it did then, just that the cross is smaller in dimension (Jamieson, Zubova).) At the time, England and Scotland had joined together as the Kingdom of Great Britain, so building a church means that the Anglicans can reach more people to proselytize. The church serving as a place for naval captains to register events that occurred on their ships also supports the fledgling British Empire, which would soon have its footholds in the Indian Subcontinent, West Africa, North America, and the Caribbean. The people working in Poplar would likely have been white ethnics (Irish, Italians, Eastern Europeans) or people of color (British History Online), and non-Protestants or non-Christians who would be doing domestic work (nannying, cooking, laundry), manual labor (building ships, unloading ships, etc.), or other types of labor that didn’t pay well, which entrenched the cycle of poverty into the East End.

Cryer, A.B. “St. Anne’s Limehouse Explained.” Everything Explained Today, n.d., https://everything.explained.today/St_Anne%27s_Limehouse/. Jamieson, Kate. “History of the Naval Ensign.” The Trafalgar Way, 17 Oct. 2019, https://www.thetrafalgarway.org/blog/history-of-the-naval-ensign. Munks, Holly. Photograph of St. Anne’s Limehouse, showing the clocktower. Poplarlondon.co.uk, n.d., https://poplarlondon.co.uk/st-anne-s-church-limehouse-history/. Munks, Holly. “Watching over Limehouse: the secret history of St Anne’s Church.” Poplar LDN, 21 May 2024, https://poplarlondon.co.uk/st-anne-s-church-limehouse-history/. "Pennyfields". Survey of London: Volumes 43 and 44, Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs. Ed. Hermione Hobhouse (London, 1994), British History Online. Web. 24 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols43-4/pp111-113. “St. Anne’s Limehouse.” St. Anne’s Limehouse [organization], n.d., https://web.archive.org/web/20141222162558/http://stanneslimehouse.org/history.html. Zubova, Xenia. “The White Ensign: A brief history of the iconic Royal Navy flag.” Forces News, 2 Sep. 2022, https://www.forcesnews.com/services/navy/white-ensign-brief-history-iconic-royal-navy-flag. |

Paige McCusker |

| 1740 | Antiquarian Interest and Early DocumentationIn the mid-eighteenth century, a pioneering antiquarian by the name of William Stukeley published "Stonehenge: A Temple Restor’d to the British Druids." In this book, Stukeley believed Stonehenge was a temple built by ancient Druids, who were the priestly class of the Celtic people, long before Rome conquered Britain. He saw the monument as part of a sacred landscape, aligned with solar and celestial events, and argued that the layout of the stones had religious and symbolic meaning, particularly in relation to nature and the sun. Notably, he even described the site as resembling a serpent form when mapped out with nearby earthworks, thus interpreting the whole area as a kind of Druidic cosmological diagram. Though it is now known in modern times that Stonehenge predates the Druids by at least a thousand years, Stukeley’s work was enormously influential in associating Stonehenge to spiritual and mystical ideas as he was among the first in history to study and document the site. His detailed drawings and measurements helped preserve knowledge of Stonehenge during a time when the site was deteriorating and overlooked. Prior to his contributions, it was uncommon for people to excavate the earth looking for artifacts or prior civilizations as a means to learn more about history. Thus, Stukeley was a pioneer figure in what is British Archaeology today (Neale). Besides being one of the first serious antiquarians, William Stukeley was a noteworthy figure in British history. Early in his life, he showed interest in mapmaking and sketching, which would come in handy later in life, but worked in his father’s law firm soon after school. Realizing he was not interested in his father’s career, he attended Corpus Christi College in Cambridge to primarily study medicine, but also became interested in botany, natural philosophy, antiquities, and astronomy. Upon graduating, he went to London to learn more about the medical field and later practiced medicine in Lincolnshire. Interestingly, one of the friends he made along the way was Sir Isaac Newton. Stukeley was the first to write a biography about Newton and witnessed the apple falling from a tree that sparked the theory of gravity. Years later, Stukeley stopping practicing medicine and was ordained in the Church of England, ultimately enabling him to study the religious and historical aspects of Stonehenge (Neale). The surrounding area of Stonehenge, Wiltshire, was largely rural, made up of farmers, shepherds, and laborers in the eighteenth century. Most people living near Stonehenge were part of an economy in which they relied on agriculture, had limited access to education, and wouldn’t have understood the significance of Stonehenge the way educated elites did. There were no tourist facilities or protections for the site at the time, and locals sometimes took stones for building material or allowed livestock to roam among them. There was little sense of “preservation” as the ancient monuments were seen more as curiosities or nuisances than as national treasures (“Wiltshire”).

Sources

Neale, Fiona. “William Stukeley’s Stonehenge.” University of Glasgow Library Blog, 7, Nov. 2015, https://universityofglasgowlibrary.wordpress.com/2015/11/07/william-stu….

“Wiltshire.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Wiltshire. |

Layna Henry |

| 1740 | The London Infirmary opensSince its founding in the autumn of 1740, the Royal London Hospital, initially known as The London Infirmary and then The London Hospital, has been one of the most extensive charities of its kind. According to its website, its aim was “the relief of all sick and diseased persons and, in particular, manufacturers, seamen in the merchant service and their wives and children". As such, it gave much-needed aid to those who needed it the most, i.e. the lower-class individuals that often made their home in the Whitechapel area. |

Logan Wertz |

| 1742 to 1762 | James Bradley’s Work at the Royal ObservatoryA site of importance as “Britain’s oldest purpose-built scientific institution,” Greenwich’s Royal Observatory, located in Greenwich Park, celebrates its 350th anniversary in June 2025. King Charles II ordered the creation of the Royal Observatory to advance knowledge in navigation and astronomy, focusing on the study of longitude to increase safety in sea travel. As sea trade was imperative for the economy and relations between countries, it was important to ensure that sailors, ships, and their goods remained safe and knowledgeable about their position while on the seas. The architects built the observatory upon the old Greenwich Castle as that land already belonged to the British monarchy and the land was secluded yet close enough to London (“History of the Royal Observatory”).

James Bradley was the third Astronomer Royal in 1742-1762 who had made over 60,000 observations in this time frame. The title Astronomer Royal, created by King Charles II, is treated as an honor given to renowned astronomers that advise the crown in matters of astronomy (“The Astronomer Royal”). Astronomy work ran in his family as his uncle, Reverend James Pound, was a leading astronomical observer in England with a connection to second Astronomer Royal Edmond Halley, whom they both worked with. He was best known for two discoveries: the aberration of light, “which produces an apparent motion of celestial bodies about their true positions,” and the nutation of the Earth's axis, the variation over time of the axis of rotation’s orientation, caused by gravitational forces (Falconer et al.). Bradley’s observations “are the earliest from anywhere in the world whose accuracy and consistency is such, that are still of use to astronomers today” (Dolan).

During his time as an Astronomer Royal, he also worked on observing the moon and Jupiter, updating the equipment at the Observatory, and defined the Bradley meridian used in the Ordnance Survey (“James Bradley”). His work helped lead to the world’s inclusion of the Greenwich Meridian and Greenwich Mean Time. Unfortunately, none of his observations were published until 1798, aside from two published by Edmond Halley in 1718.

Works Cited: Dolan, Graham. “The Royal Observatory Greenwich – A Brief History.” The Royal Observatory Greenwich, The Royal Observatory Greenwich, 2014, http://www.royalobservatorygreenwich.org/articles.php?article=1 Falconer, I.J.; Mena, J. G.; O’Connor, J.J.; Peres, T.S.C.; & Robertson, E.F. “James Bradley.” MacTutor, 2018, https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Bradley/#:~:text=Bradley%20was%20best%20known%20for,the%20velocity%20of%20the%20observer “History of the Royal Observatory.” Royal Museums Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/royal-observatory/history “James Bradley.” Royal Museums Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-203215 “The Astronomer Royal.” Royal Museums Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/astronomer-royal Wilson, Benjamin. James Bradley. ca. 1750, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London |

Emera Gregor |

| 1745 | Chelsea Porcelain Factory FoundedIn the 18th century suburb of Chelsea, the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory created some of the finest pieces of British porcelain. The factory, founded by Frenchmen Nicholas Sprimont and Charles Gouyn, catered to wealthy Londoners. Being founded by two Frenchmen is symbolic of the large French population in the area, as many Huguenots chose to settle in the city and specifically in that area. Chelsea China was produced at 16 Lawrence Street, Chelsea from 1745 to 1784. The area of Chelsea was a fashionable area, a trait that would continue for the area’s history. Notions of class and wealth have proved to be key areas of discussion for much of the area’s history, as even today there is notable wealth inequality. Boucher, François. The Music Lesson. ca. 1765. The Met. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/203386. Accessed 18 April 2023. “Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory: Finch: British, Chelsea.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/658952. Accessed 18 April 2023. |

Kathryn Maille |

| 1753 | The Establishment of the British MuseumIn 1753, an Act of Parliament created the world's first free, national, and public museum: the British Museum, located in Bloomsbury, London. The current collection of artifacts in the British Museum consists of around 8 million items that span across 2 million years of human history, although only 1% (80,000) of the objects are on public display. One of the largest contributors to this collection was Sir Hans Sloane. He was known as a collector of artifacts from around the world. Upon his death in 1753, he gifted his collection of over 80,000 “natural and artificial rarities” to Great Britain. Thus, the Sir Hans Sloane collection became what is considered the founding collection of the British Museum. These items also became the foundation of the British Library and the Natural History Museum. The British Museum’s collection was originally housed in the 17th century mansion, Montagu House. It was refurbished multiple times before and after the museum became open to the public in 1759 to make room for the massive collection. However, more room was still needed to hold the British Museum collection, so in 1823 the Montagu House was demolished. In its place came the museum that we know today, Sir Robert Smirke’s enormous Greek Revival style building. This new home for the British Museum collection was completed in 1852. The British Museum’s building and artifact collection are both being expanded and developed to this day. Sources: “History.” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/history “Sir Hans Sloane.” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/sir-hans-sloane “Fact Sheet - British Museum.” The British Museum , https://www.britishmuseum.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/fact_sheet_bm_collection.pdf |

Margaret Wetzel |

| 1754 | Kenwood House is purchased by the 1st Earl of MansfieldKenwood House, estimated to have been originally built in 1616 and was home to the Earls of Mansfeild. It was later demolished and rebuilt by the Surveyor-General of the Ordnance, William Bridges and sold in 1704 and shifted many owners until the Earl of Mansfield, William Murray, purchased it in 1754. In 1764, Murray commissioned Robert Adam to remodel the house for him. He added the most iconic and well-known area of the house: the library. It was donated to the London City Council and opened to the public in 1927 as a museum of sorts.

In mid-1790, the house was ransacked as part of the Gordon Riots. While most of the rioters just stole food, many items such as mirrors and paintings were ransacked as well. Murray and his wife fled the house during this time, which allowed the ransacking of the space. The Gordon Riots took place in London over several days to protest anti-catholic sentiments. The riots were a response to the Popery Act of 1698 which enforced stricter laws onto the British people. Kenwood was just one of the casualties of the Riots, as British Banks and Prisons were targeted too.

After Murray’s death in 1793, Kenwood was inherited by his son, David Murray the 2nd Earl of Mansfeild. It was passed down for generations until the 6th Earl of Mansfielddecided to sell it in 1906 and leased it to the exiled Grand Duke Michael Mikhailovich of Russia. It was finally bought in 1922 by the Kenwood Preservation council and opened to the public as it contains many historical and art pieces.

Today, Kenwood still contains paintings like Self Portrait with Two Circles, by Rembrandt, along with many other classical pieces. It is currently under the ownership of the Friends of Kenwood and The English Heritage Trust. Work Cited “Friends of Kenwood Archive .” Friends_of_Kenwood, 20 Oct. 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20191020115019/http://www.friendsofkenwood…. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023. “Kenwood.” English Heritage, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/kenwood/?utm_source=aw…. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023. “Kenwood House front with extensions.” 27 Nov. 2005 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kenwood_House_front_with_extensions_2005.jpg Accessed 18 Feb. 2023. “Kenwood House (Iveagh Bequest), Non Civil Parish - 1379242: Historic England.” , Non Civil Parish - 1379242 | Historic England, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1379242. Accessed 18 Feb 2023.

|

Allison Schroeder |

| 1760 to 1760 | The Demolition of Bishopsgate (Bishop's Gate)In 1760, the medieval Bishop's Gate, one of the original entrances through the London Wall into the City, was demolished as part of broader urban modernization efforts. The gate, named for its historical association with the Bishop of London, had stood since at least the Roman era and had been rebuilt several times over the centuries. Its removal reflected a shift in London's urban priorities, from defense and to a freer movement and trade. As London's population grew and inevitably commerce expanded, old city gates were increasingly seen as impediments to traffic and development. The demolition of Bishop’s Gate, now known as Bishopsgate, was both practical and symbolic: it represented the city's evolution from medieval stronghold to a center of global commerce and enlightenment-era civic planning (Weinreb et al. 2008; Schofield 1994). Porter, Roy. London: A Social History. Harvard University Press, 1995. Accessed April 23, 2025 Schofield, John. The Building of London: From the Conquest to the Great Fire. Sutton Publishing, 1994. Accessed April 23,2025 Weinreb, Ben, et al. The London Encyclopaedia. 3rd ed., Macmillan, 2008. Accessed April 23, 2025 |

Hollie Keller |

| Sep 1768 | Opening of the London TavernDuring the 18th century, London was home to many coaching inns and taverns that served as places of rest for travelers. Bishopsgate and surrounding regions were ideal spots for such inns, as, upon the popularization of stagecoach travel in the 17th century, travelers often entered through Bishop’s Gate, an old Roman entrance to the city (McLachlan). One notable inn from this period is the London Tavern, built in September 1768 on the former site of the White Lion Tavern, which had been destroyed in a fire three years prior. The London Tavern notably featured a large dining room with ornate Corinthian columns and other elaborate ornamentation. According to the contemporary account of John Timbs in his Club Life of London, Vol. II, this dining room could hold at least 300 dinner guests for banquets (274). Timbs also further elaborates on the tavern’s decoration, writing, “The walls are throughout hung with paintings; and the large room has an organ,” (274). Even shortly after its opening, the London Tavern was the site of numerous important meetings and events. In 1769, for instance, around 400 men formed the Society of the Supporters of the Bill of Rights in the London Tavern (Cash 249). The Society was dedicated to supporting John Wilkes, a controversial member of parliament who championed the individual rights of people associated with the American Revolution and who introduced the first ever motion in the House of Commons to allow for the voting rights of all adult males (Cash 2). Another London Tavern meeting of historical importance is that of the Revolution Society, a group sympathetic to the ideals of the French Revolution that celebrated the cause of the Glorious Revolution, which met in the tavern in 1789 shortly after the fall of the Bastille (Abstract of History 8). In the subsequent century, the London Tavern was also visited by Charles Dickens, who presided over a meeting there in 1841 for the benefit of the Sanatorium for Sick Authors and Artists, and who also attended another dinner there in 1851 for the General Theatrical Fund (“London Tavern”). The London Tavern also makes a direct appearance in Dicken’s novel Nicholas Nickleby (Dickens).

Abstract of the History and Proceedings of the Revolution Society, in London. Revolution Society, 1790, https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_an-abstract-of-the-histo_revolution-society-lond_1790/mode/2up. Pamphlet. Cash, Arthur H. John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty. Yale University Press, 2007. Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, 1839. Project Gutenberg, 2016. Engraving of the London Tavern in 1809. Wikipedia, 1809. https://d245m47bicpi64.cloudfront.net/_imager/files/Activities/Archives/46476/WR-3_36ec1335269ad97502c26586ba96154b.png. Accessed 17 Apr. 2023. “The London Tavern.” The Worshipful Company of Bowyers, https://www.bowyers.com/meetingPlaces_londonTavern.php. Accessed 17 Apr. 2023. McLachlan, Sean. “Travel Through Time at England’s Coaching Inns.” British Heritage Travel, 10 Apr. 2023, https://britishheritage.com/travel/travel-englands-coaching-inns. Accessed 17 Apr. 2023. Timbs, John. Club Life of London, Vol. II. Richard Bentley, 1866. |

Travis Saylor |

| 2 Jun 1780 to 9 Jun 1780 | The Gordon RiotsThe Gordon Riots of 1780 serve as some of the most violent pieces of recorded Westminster history, displaying the horrid effects of intersecting religion and politics, or church and state in 18th-century England. The riots began as an aggressively anti-Catholic response to the Catholic Relief Act (Papists Act) of 1778. The Catholic Relief Act aimed to cut back on the discrimination against Roman Catholics, allowing these individuals to join the army and own property, among other basic rights. However, the Protestants did not agree with this new way of life, as they viewed Roman Catholics as being a threat to Britain’s identity. The leader of the Protestant Association, Lord George Gordon, became the face of this backlash, acting as a voice for the Protestants who decided that Catholics would now be able to infiltrate the military and commit treason. All of the anger and backlash from the Protestants culminated on June 2nd, 1780. Nearly 60,000 of the protestors gathered in St. George’s fields, then were led to Parliament by Gordon himself to present to them a petition to repeal the Catholic Relief Act. The main idea to keep in mind is the fact that the confrontation started out peacefully. However, this peace was short-lived. Their demonstration quickly turned extremely violent, with members of Parliament being attacked, Catholic churches and homes being targeted, etc. Over the following few days, the chaos only got worse. June 7th of the same year came to be known as “Black Wednesday,” due to the sheer amount of dark violence brought on by the rioters. Prisons such as Newgate were burned to the ground, freeing prisoners and harming others, and the Bank of England was nearly stormed, leading King George III to declare martial law on the country. By that Friday, the riots had ended, but not without significant loss. Aside from the damages caused by looting and arson, it is estimated that 300 people lost their lives in the short time span. Luckily, some justice was brought to these people, as about 450 rioters were arrested afterward, with 25 of them being hanged. As for Lord Gordon himself, he was sentenced to eight years in prison and was tried for high treason, though acquitted as they could not hold him solely responsible for the rioters’ actions. In the end, the Gordon riots displayed to the public the sheer scope of violence that can occur when civilians band together. They proved to the country that effective law enforcement is crucial, and they starkly underlined class tensions in Great Britain, where issues of religion, government, and social class intersected harshly. These riots serve us today as a clear example of a time in history not worth repeating. Resources: “Spotlight on: Gordon Riots.” The National Archives, The National Archives, 28 Mar. 2025, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/students/videos/spotlight-on/spotlight-on-gordon-riots/. “The Gordon Riots: How an Anti-Catholic Petition Escalated into the Most Destructive Riots in London’s History.” HistoryExtra, HistoryExtra, 20 Aug. 2024, www.historyextra.com/period/georgian/gordon-riots/#. “The Gordon Riots: London in Flames.” London Walks, www.walks.com/blog/gordon-riots-london. “History of the Gordon Riots.” EBSCO Research Starters, www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/gordon-riots. Gresham College. “The Gordon Riots of 1780: London in Flames, a Nation in Ruins.” Gresham College, www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/gordon-riots-1780-london-flames-nation-ruins. “Gordon Riots.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gordon_Riots |

Amelia Vachon |

| circa. The start of the month Summer 1780 to circa. The start of the month Summer 1780 | The Closing of The Clink (18th century)The Clink is known as the "most notorious medieval prison"; is also one of the oldest and was in use from 1144 to 1780. The conditions for prisoners here were absolutely horrendous, and most were there because they had debts they couldn't pay. But the prison was originally for heretics. They were all often subject to grueling torture and rooms that regularly flooded, causing bodies to rot from not being able to dry. The clink had two distinct sections, one for men and the other for women. The only way for prisoners to get relief from the torture is if they were lucky enough to have someone on the outside to give money as a bribe to the jailors. These bribes could also bring them more comfortable amenities and food during their stay. Usage of this prison decreased as the years passed, but it was always a loathed place for many. Then in 1780, The Clink was broken into during the Gordon Riots, which were led by Anti-Catholic Protestant Lord Geroge Gordon. That night the rioters freed all prisoners that were still in The Clink before setting the whole thing ablaze. The Click was not ever rebuilt or used again after those riots, and many, if not all, escaped prisoners were not captured again. Today there is a Clink museum in the same spot in Southwark where the prison was originally, but all that still stands from the original is one brick wall. The Clink Museum. The Rich and Gory History of the Clink Prison. clink.co.uk/history-of-clink.html The British Library. Map of the Gordon Riots. www.bl.uk/learning/timeline/item104674.html Ian Haywood. The Gordon Riots of 1780: London in Flames, a Nation in ruins. Grahamn College. March 11, 2013

|

Danielle West-Habjanetz |

| 1791 | Camden TownAs Camden Town and the greater Borough of Camden itself started out as barely a grouping of a few houses alongside a main road, it was not until much later that they gained their names after their namesake, Sir Charles Pratt, the first Earl of Camden. Sir Pratt obtained the area of Camden Town through marriage in 1791, specifically the land that was once upon a time the manor of Kentish Town, but death claimed the man just three years later, in 1794. While the Borough of Camden did not become established until much later on April 1st, 1965, Camden Town slowly began to grow in popularity over the years. As the world made progress with the industrial revolution during the 19th century and railways and canals were built through the location and became adapted to serve a transportation function, they also brought with them new life. Still, Camden Town was deemed an unfashionable area until change struck again in 1973, when the old warehouses and similar buildings were transformed to serve as tourist destinations. It still contains a significant number of methods of transportation throughout in order to accommodate the large amount of tourism in the area, simply having switched over from shipping goods to transporting people over the years. Areas like the Camden Catacombs, which were initially built for the transportation of goods (and not to serve as an underground cemetery as the name would suggest) but could not be converted into stores or walkways due to public safety concerns, were either closed off to tourists or became submerged below the water level. Having housed a variety of popular figures over the years as well, Camden Town has made many appearances in various forms of media and is now a well-known name to those even outside of London.

“Camden Town.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 Apr. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camden_Town |

Sophia Girol |

| 1795 | Construction of Barracks in KnightsbridgeIn the 1700s, Knightsbridge was a very different place from what it is now. All throughout the 18th century, Knightsbridge was in very early stages of development with very few new buildings and unpaved, unlit streets, which is a very stark contrast to the Knightsbridge of today. However, following the French Revolution, tensions were high and the threat of soldiers being corrupted by revolutionary influences were very high. Following urban riots in 1792, the government decided the best course of action would be to build barracks in an effort to isolate the soldiers and slow the threat of revolutionary influence on them, so they built a new set of barracks in Knightsbridge. These barracks were quite different from past calvary barracks that had been constructed throughout the years in Britain.

"Knightsbridge Barracks: The First Barracks, 1792-1877." Survey of London: Volume 45, Knightsbridge. Ed. John Greenacombe. London: London County Council, 2000. 64-68. British History Online. Web. 18 April 2023. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol45/pp64-68. |

Noah Meckes |

| 1801 | Establishment of Russell SquareRussell Square was established in 1801 by Francis Russell, the fifth Duke of Bedford. He commissioned James Burton, the most successful developer at the time, to design and construct the buildings. Russell square was the centerpiece of Russell’s development plan for Bloomsbury to increase economic activity. This plan was extremely successful. Russell Square was the largest square in London at the time, and one of the most desirable places to live in. Not only was Russell Square built in Bloomsbury, the intellectual and literary capital of London, but the square is also within walking distance of The British Museum and Oxford Street. Russell Square quickly became home to the highest of society. Some of the famous residents of Russell Square include the influential poets Thomas Grey, William Cowper, and T.S. Eliot. After the establishment of Russell Square in 1801, Bloomsbury became filled with countless scientists and artists, as shown in Michael Boulter’s novel, “Bloomsbury Scientists." Sources: “Russell Square.” Hidden London, https://hidden-london.com/gazetteer/russell-square/. “Russell Square.” Bloomsbury Squares & Gardens, 30 Nov. 2021, https://bloomsburysquares.com/the-squares/russell-square/. Trimatis, Killian. “A Brief History of Bloomsbury.” TripTide, https://triptide.london/journals/bloomsbury-history. Boulter, Michael. Bloomsbury Scientists PDF. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1573504/1/Bloomsbury-Scientists.pdf. |

Margaret Wetzel |

| 1802 | East/West India DocksThe West and East India Docks would be built in 1802 for unloading cargo from both companies: spices from India (East India Company); and the occasional enslaved person, as well as goods like rum, sugar, and cotton from the British West Indies (Encyclopedia Britannica). These were the two companies that expanded the British Empire's reach. The Poplar Docks would've connected to the West India Docks to serve as a reservoir. Then it was converted into a timber pond (1844) and into a railway dock (1850-1851) to move coal around and export other goods (British History Online). As mentioned above, the East India Company in particular served as the hand of the British Empire, not only getting in on the spice trade in India, but then partaking in the Transatlantic Slave Trade, in which they transported people from Africa to India and Indonesia, as well as to the Caribbean and the Southern United States (Alabama, Florida, Georgia) along the Middle Passage (Encyclopedia Britannica). India in particular would find itself completely kneecapped by the colonization of the British. India was effectively entirely conquered by the 1820s and supplying the Empire with raw materials like cotton, silk, saltpeter for gunpowder (Encyclopedia Britannica). During this time, there would be an influx of immigrants from overseas who were poor. They would follow typical immigration patterns seen around the world - Irish, Eastern European, then Chinese, Indian, etc. - and work in occupations like bricklaying, factory work, unloading docks, servitude, etc. Around the 1880s would be an influx of Chinese, Japanese, and Lascar (from Somaliland, Indian Subcontinent, Arab World, Southeast Asia) immigrants, who would land in the Pennyfields section of Poplar and expand out as more and more people of that heritage worked on British ships. They would also build opium dens or brothels (British History Online).

Daniell, William. An Elevated View of the New Docks & Warehouses now constructing on the Isle of Dogs near Limehouse for the reception & accommodation of Shipping in the West India Trade. 1802. The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_G-13-17. Accessed 20 Apr. 2025. Editors, Encyclopedia Britannica. “East India Company.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 Jan. 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20200910045538mp_/https://www.britannica.com/topic/East-India-Company. Accessed 20 Apr. 2025. Editors, Encyclopedia Britannica. "India - Colonialism, Mughal Empire, Trade | Britannica." Encyclopedia Britannica, upd. 24 Apr. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/India/The-British-1600-1740. Accessed 24 Apr. 2025. "Pennyfields". Survey of London: Volumes 43 and 44, Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs. Ed. Hermione Hobhouse (London, 1994), British History Online. Web. 24 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols43-4/pp111-113. Accessed 24 Apr. 2025. "Poplar Dock: Historical development". Survey of London: Volumes 43 and 44, Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs. Ed. Hermione Hobhouse (London, 1994), British History Online. Web. 21 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols43-4/pp336-341. Accessed 23 Apr. 2025. |

Paige McCusker |

| 1802 | The Regent's CanalThe Regent’s Canal, first brought up in a proposal in 1802, did not begin its actual construction until October 14th, 1812. After many years of labor, the canal was finally opened in all its glory on August 1st, 1820. However, the first section, which stretches from Paddington to Camden Town, was opened to the public in 1816, facilitating early transport and commerce in the area. Spanning a total length of 8.6 miles, the Regent’s Canal serves as a vital link between the Paddington Arm of the Grand Union Canal and the Limehouse Basin and the River Thames. The canal played a crucial role in propelling Camden headfirst into the industrial revolution, which was later further amplified in the area by the addition of the North Western Railway’s terminal stop in Camden in 1837. These developments not only boosted local trade but also transformed Camden into a bustling hub of industrial activity and, eventually, tourism. As the years went by and the canal’s use began to shift from mainly shipping goods over greater distances to transporting people locally, the Central Electricity Generating Board decided to install underground cables below the towpath between St John’s Wood and City Road in 1979, forming part of the National Grid that supplies electrical power to London by using the canal water as a coolant for the high-voltage cables and keeping the dangerous and unsightly equipemnt out of the way of the population in the area. In an act to celebrate its 200th anniversary, not too long ago in 2012, the playwright Rob Inglis was awarded a substantial grant in order to fund the creation of the musical Regent’s Canal, a Folk Opera in its honor, celebrating the digging of the canal and all the location has done for the area of Camden and also London overall.

“Regent’s Canal.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 9 Mar. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regent%27s_Canal |

Sophia Girol |

| 17 Oct 1814 | The St. Giles Beer FloodThe London Beer Flood occurred on October 17th, 1814 when the pressure from a 1 million pint beer barrel exploded in the Meux & Co's Horse Shoe Brewery, causing many other barrels to break and begin to flood the brewery, into the streets. Around 570 liquid tons of beer crashed into other barrels quickly flooding the brewery. The force of the explosion caused the bricks of the building to collapse and flood St. Giles neighborhoods, killing eight people.

The clerk in charge of maintenance that day was George Crick, who survived the flood. He noticed a broken 700- pound hoop on the barrel that had slipped off and decided to let another employee fix it the next day. Before long the barrel had exploded from the pressure, covering the St. Giles Neighborhood in mere minutes. Despite his negligence, the clerk and the brewery were cleared of any wrongdoing by a jury and declared that the caulsties lost their lives by an “act of God,” and that they had died “casually, accidentally and by misfortune.” All of the people inside the brewery survived.

Anne Saville was one of the casualties, along with four other people mourning the loss of her two year old son at his wake near to the brewery. The people of St. Giles took to the streets, wading through nearly two feet of beer, in search of people who survived by climbing onto furniture.

The flood occurred in St. Giles which was a parish of Holbourn that would later form the Borough of Camden. The brewery stood on the corner of Tottenham Court Road, and became an attraction after the flood for a short period of time. Watchmen would charge two-pence for people to see the rubble of the accident. The Brewery would suffer an economic loss, but received a break on the taxes that they had already paid the government.

Works Cited “Horseshoe Brewery, London, c. 1800.jpg.” 15 Feb. 1906. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Horseshoe_Brewery,_London,_c._1800.jpg Accessed 18 Feb. 2023. KLEIN, CHRISTOPHER. “The London Beer Flood.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 9 Oct. 2019, https://www.history.com/news/london-beer-flood. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023. Tingle, Rory. “What Really Happened in the London Beer Flood 200 Years Ago?” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 17 Oct. 2014, https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/what-r…. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023. |

Allison Schroeder |

| 24 May 1819 | Queen Victoria is Born in 1819On May 24, 1819, Alexandrina Victoria was born in the dining room of Kensington Palace amid the “baby race” of the potential succession crisis looming of the late 1810s, delivered by the same woman who also delivered her first cousin and future husband Albert. She grew up in Kensington Palace as well, provided with many talented teachers and tutors but restricted under the “Kensington System.” She resented the restrictive nature of the system’s rules imposed on her by her mother and Sir John Conroy, whom her mother depended on after her husband and Victoria’s father died. Despite this, she was able to tour the country and was seen as a new hope for the country as she was not associated with the negative parts of the dynasty. In the early morning of 20 June 1837, she learned she was then Queen Victoria, as her uncle, the king, had died. Wilkie, David. Victoria, Duchess of Kent, (1786-1861) with Princess Victoria, (1819-1901). 1821. Royal Collection. https://www.rct.uk/collection/407169/victoria-duchess-of-kent-1786-1861-with-princess-victoria-1819-1901. Accessed 18 April 2023. Wilkie, David. The First Council of Queen Victoria. 1838. Royal Collection. https://www.rct.uk/collection/404710/the-first-council-of-queen-victoria. Accessed 18 April 2023. “Growth of a Victorian Suburb.” The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, https://www.rbkc.gov.uk/vmhistory/general/vm_hs_p10.asp. Accessed 18 April 2023. |

Kathryn Maille |

| 16 Oct 1834 to 16 Oct 1834 | The Burning of the Houses of ParliamentThe burning of the Houses of Parliament on October 16, 1834, was one of the most notable events that occurred in 19th-century England. The fire destroyed centuries of architectural history and represented the fall of their old political structure, as well as the rise of a new, more modern one. The fire began due to a seemingly mundane act: the Exchequer (treasury) was attempting to get rid of wooden tally sticks—old accounting tools used to record debts and other monetary data. In an attempt to dispose of old bookkeeping materials, two loads of the sticks were burned in the furnaces that lay underneath the House of Lords. Unfortunately, the furnaces were poorly taken care of, and the resulting blaze sparked the massive fire, quickly spreading to both the Lords’ and Commons’ chambers (Wilson, 2004). Crowds gathered along the River Thames as the flames grew and spread, reflecting off the river and illuminating all of central London. Artist J.M.W. Turner, who watched the fire from a boat on the river, painted several dramatic pieces portraying the event that still survive today as powerful visual depictions (Tate Britain, n.d.). Despite the intensity of the fire, there were no lives lost, thanks in part to the time of day (night) and the rapid efforts of firefighters. However, the damage to the buildings was detrimental. The Palace of Westminster, which had held Parliament for centuries, was destroyed. Only Westminster Hall, the Jewel Tower, and a few other parts of the area were able to survive. The destruction of the Parliament buildings presented a unique opportunity. England was undergoing severe social and political transformations, especially due to the Reform Act of 1832, which grew the electoral franchise and reduced the power of the aristocracy. The fire was seen by some as divine intervention on a corrupt political system in need of reform (Gilmour, 1992). Post-fire, a competition was held to lay out a new complex for parliament. The winning design by Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin resulted in the Gothic style architecture we now refer to as the Palace of Westminster. Completed over the following decades, it mixed medieval and modern aspects, serving as a nod to Britain’s past while also suggesting its brighter future. This improved building also served as a physical expression of the Victorian era’s values, including order and progress. Ironically, it was during the rebuilding that the British Parliament would establish itself as more of a democracy, expanding suffrage and becoming more representative of its population. To conclude, the burning of the Houses of Parliament was more than just a tragedy; it was the beginning of an important transformation. It marked the literal and figurative end of an old government, and the improved beginning of the British parliament as we recognize it today. Sources: Gilmour, Robin. The Victorian Period: The Intellectual and Cultural Context of English Literature, 1830-1890. Longman, 1992. Tate Britain. “The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons.” Tate Gallery, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-the-burning-of-the-houses-of-lords-and-commons-october-16-1834-n02068. Wilson, David. The Building of the Victorian Parliament. Routledge, 2004. Parliament.uk. “The 1834 Fire.” UK Parliament, www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/building/palace/fire-1834/ |

Amelia Vachon |

| 1837 to 1897 | Queen Victoria Moves Into WindsorQueen Victoria took the throne in 1837, at only 18 years old, and chose Windsor Castle as her primary royal residence. Windsor held many of Queen Victoria’s important milestone events. She held her 20th birthday ball at the castle, her honeymoon with Prince Albert, and Windsor became a headquarters for her family life as they raised their children. Throughout their time at Windsor, the castle underwent many renovations and modernizations. Many of these renovations followed along with what is now known as Victorian architecture and design, named after the queen herself. During this time, Queen Victoria influenced the shift of royal family burials from Westminster Abbey to St. George’s Chapel at Windsor. In 1861, Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, passed away at Windsor Castle. This caused her immense grief and changed her opinion of Windsor Castle. She described the castle as “prison-like” and likened it to a dungeon. Prince Albert’s death in Windsor caused Queen Victoria to memorialize The Blue Room, where he died, and turned it into a sacred shrine to honor him and some other royals who passed away in the room including King William IV and King George IV. Queen Victoria’s milestones continued in 1897 when she celebrated her 60th year on the throne with her diamond jubilee at Windsor. The monumental occasion was held on June 20th, 1897 with a private celebration in St. George’s Chapel. This marked the end of her long relationship with Windsor, as she passed away 4 years later. At the time, she was the longest reigning British monarch, serving for 64 years. Bell, Nicola. Queen Victoria Statue. www.windsor.gov.uk/ideas-and-inspiration/royal-connections/queen-victor…. Accessed 23 Apr. 2025.

Royal Collection Trust. “Queen Victoria.” Www.rct.uk, 2024, www.rct.uk/collection/stories/royal-jubilees/queen-victoria-0. Accessed 23 Apr. 2025. Timms, Elizabeth Jane. “Queen Victoria and Windsor Castle.” Royal Central, 1 Apr. 2018, royalcentral.co.uk/features/queen-victoria-and-windsor-castle-99279/. Accessed 23 Apr. 2025. Wicks, Lauren. “A Brief History of Windsor Castle, the World’s Longest-Occupied Palace.” Veranda, 9 Nov. 2022, www.veranda.com/decorating-ideas/a36077169/windsor-castle-history/. Accessed 23 Apr. 2025. |

Noah Meckes |

| 28 Jun 1838 | Queen Victoria's coronation

On May 24th, 1819, Alexandria Victoria was born at Kensington palace to Prince Edward and Princess Victoria. At the time of her birth, she was the heir to the throne after her father. He died shortly thereafter when she was eight months old. On June 20, 1837, at only 19, princess Victoria was informed that she would be crowned queen, as William the Fourth had passed that morning. She was then coronated on June 28th, 1838 at the Westminster Abbey. There were a considerable amount of mistakes on her coronation day, as it was poorly rehearsed. An elderly peer fell down the steps while making his homage to her, and the coronation ring was put on the wrong finger. However, Queen Victoria was still very excited and proud to be queen. Queen Victoria, who ruled over part of the industrial expansion of Britain and helped fuel it into an empire, is often known for her relationship with her husband, Prince Albert. Despite being an arranged marriage, the couple was very much in love, and their display of a loving family unit was impactful on the rest of Britain. It changed the cold and stoic ideas normally surrounding the royal family, and also influenced the way romantic and familial relationships functioned in the public - such as their public affection and gift-giving. The couple also contributed largely to the arts; painters, sculptists, and the performing arts. Many of their gifts to each other were commissioned art pieces. Even after death, their love was strong, as Queen Victoria mourned Prince Albert’s death until her own.

Hawksley, Lucinda. “Victoria and Albert: How a Royal Love Changed Culture.” BBC Culture, BBC, 24 Feb. 2022, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20150623-victoria-albert-cultural-i…. “Queen Victoria.” Westminster Abbey, https://www.westminster-abbey.org/abbey-commemorations/royals/queen-vic…. “Queen Victoria.” Historic Royal Palaces, https://www.hrp.org.uk/kensington-palace/history-and-stories/queen-vict…. |

Kierra Weyandt |

| 1849 | Harrods Grand Opening in KnightsbridgeIn 1849, Henry Charles Harrod founded and opened Harrods department store in Knightsbridge. Harrods has been a staple in Knightbridge ever since this time. It has played a very large role in the affluent environment and society that is still present in Knightsbridge today. Harrods department store started as a one room grocery store in Knightsbridge, and by the 1880s it had expanded into clothing, perfume, food, and medicine. It has now turned into a seven-story luxury department store with over 300 departments where the wealthiest people throughout London and surrounding areas shop. In 1883, Harrods was the scene of a devastating fire which burnt the entire building to the ground. However, Harrods came back bigger and better than ever with a very large expansion encapsulating over one million square feet, allowing it to expand into more departments and cater to larger groups of people. Over the course of the last 200 years, Harrods has changed ownership multiple times, with the most recent owner being the state of Qatar. Throughout the years, Harrods has faced many ups and downs, its existence has played a very prevalent and major role in the history of the Knightsbridge area in London.

BBC. “History of Harrods Department Store.” BBC News, 8 May 2010, www.bbc.com/news/10103783. Accessed 18 Apr. 2023. Fashion ABC. “Harrods.” Fashionabc, 2023, www.fashionabc.org/wiki/harrods/. Accessed 18 Apr. 2023. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Harrods | Store, London, United Kingdom | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/Harrods. Accessed 18 Apr. 2023. |

Noah Meckes |

| 1855 | Construction of The Greenwich TheatreThe Greenwich Theatre was built in 1855 by Sefton Parry and was used by the great festival of the Greenwich Fair. The original use was mostly by the Richardson traveling theatre that performed frequently to the masses. The theatre shows an interest in growing the population for drama and theatrical performances. The Richardson traveling theatre would visit the area annually and put on performances of all sorts. The theatre would be rebuilt in 1871 and be named the “Crowder’s Music Hall” and have more musically based performances. The actual theatre would be rebuilt multiple times and go under several shifts in its name and type of art performed. It’s interesting to see how as time goes by and the art changes there is still serious interest by the population as time went on. While the theatre would never reach the heights of the Golden Globe and other theatres in London, there was still a population of people who sought to preserve the theatre whenever it was threatened to be torn down. There have been several reconstructions and rebuilding of the theatre, but it has yet to be ever torn down. The original capacity of the theatre was only 423 seats, but it was said that it would be full when the Richardson traveling theatre came to Greenwich. Even during WWII, the theatre was several damaged by an incendiary bomb that torched a good bit of the inside. However, it was reconstructed. To this day, live performances are still being put on. I don’t think that many people would go out of their way to visit the theatre or even stop in passing to see what it was about, but it still holds a sentimental value to the people of the area. The local history of the theatre is what has saved it and rebuilt it every time.

Sources: “Our History.” Greenwich Theatre, 13 Mar. 2023, https://greenwichtheatre.org.uk/about/. “Theatres and Halls in Greenwich, London.” Theatres and Halls in Greenwich, London, http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/Greenwich.htm. |

Aidan Pellegrino |

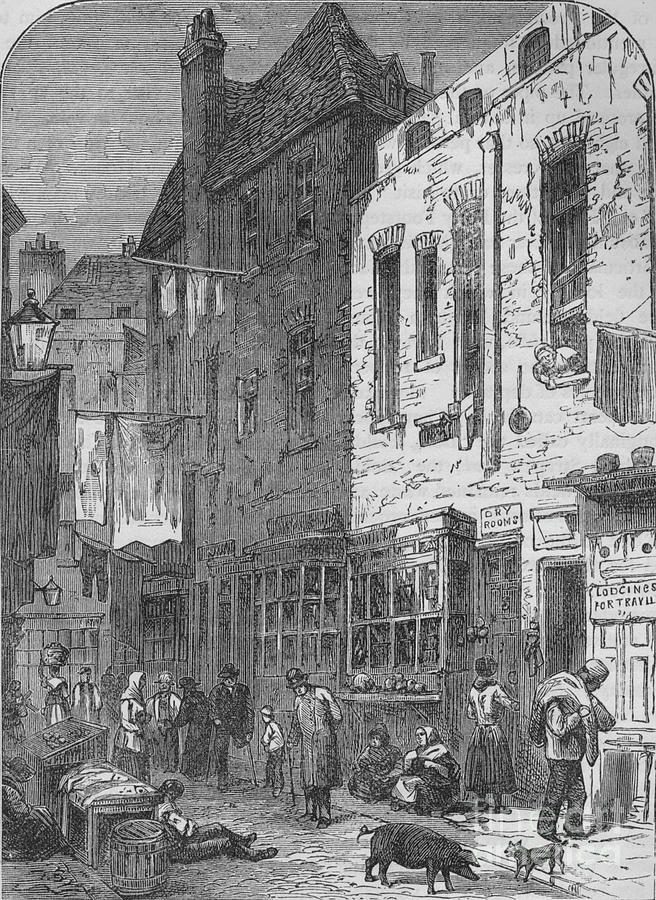

| 1860 | The Separation of Classes Through Rookeries and PalacesThe 1800s ushered in the Regency period from 1811-1820 of architecture with figurehead John Nash prompting Regency Classism through the dominant use of stucco. During this period industrial labor migration flourished and poverty grew as an outcome to the changes in the labor market. The discrepancy between the housing of the royals versus those of the slums was prominent during this time. A slum was referred to as a rookery during the 18th and 19th centuries with a famous rookery located within the St. Giles area of London. Those who enjoyed this era of British culture were the wealthy few. The most defining aspect of John Nash’s legacy, ignoring his messy relationship with his first wife, was the transformation of Buckingham Palace, as well as the Roya Pavilion and Marble Arch. The Marble Arch was originally designed as the entrance to Buckingham Palace, but today it stands as the entrance to Hyde Park and The Great Expedition. Originally known as Buckingham House, it was privately owned by the Duke of Buckingham in 1703. Today, Buckingham Palace hosts the administrative headquarters of the monarchy since 1837 with Queen Victoria. With the addition of a Cour d’honneur, or an open formal forecourt and bath stone beginning in 1825 and completed in 1853. Henry Mayhew visits the rookery of St. Giles in 1860 and writes: The parish of St. Giles, with its nests of close and narrow alleys and courts inhabited by the lowest class of Irish costermongers, has passed into a byword as the synonym of filth and squalor. And although New Oxford Street has been carried straight through the middle of the worst part of its slums—"the Rookery"—yet, especially on the south side, there still are streets which demand to be swept away in the interest of health and cleanliness... They [are] a noisy and riotous lot, fond of street brawls, equally "fat, ragged and saucy;" and the courts abound in pedlars, fish-women, newscriers, and corn-cutters. Government during the 1830s-1870s demolished part of St. Giles for improved transportation routes and sanitation with the specific street being New Oxford Street. The outcome was that the slum was pushed farther back, and It failed to achieve its goal until late 1900s. “Buckingham Palace.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, https://www.history.com/topics/european-history/history-of-buckingham-p…. Mayhew, Henry. A VISIT TO THE ROOKERY OF ST. GILES AND ITS NEIGHBOURHOOD . 1860, pg 5. https://web.archive.org/web/20061010065924/http://learning.north.london…. Photograph of The Rookery of St Giles, London, 1850 by Print Collector. Photos.com, https://photos.com/featured/the-rookery-of-st-giles-london-1850-print-c….

|

Hollie Keller |

| 1864 to 1874 | The Construction of Liverpool Street StationIn 1864, work began on Liverpool Street Station, designed to replace the outdated Bishopsgate terminus of the Great Eastern Railway. Located north of Bishopsgate, the station's construction reshaped the area dramatically. Streets and housing were cleared, displacing residents and altering the neighborhood’s social demographic. Over the next decade, a vast network of platforms, iron-and-glass roofing, and railway lines emerged, symbolizing Victorian engineering ambition. By its opening in 1874, the station had become one of London's largest and most important transport hubs. It connected the growing suburbs to the City, increased commuter traffic, and attracted commerce. The surrounding area evolved from mixed residential to commercial, with warehouses, hotels, and offices replacing homes. This marked Bishopsgate’s transformation from a historic residential ward into a modern area of finance and transit, a legacy that remains evident in its urban character today. Jackson, Alan A. (1984) [1969]. London's Termini. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-330-02747-6. History of Liverpool Street station". Network Rail. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Smith, Denis (2001). London and the Thames Valley. Civil Engineering Heritage. Thomas Telford. ISBN 0727728768. |

Hollie Keller |

| 1874 | Private Ownership and Early PreservationIn 1874, Sir Edmund Antrobus, a member of the British aristocracy, purchased the land on which Stonehenge stands. Although Stonehenge had long been in private hands, the Antrobus family's acquisition of the site corresponded with growing national interest in Britain’s ancient monuments and laid the groundwork for future preservation efforts and archeological discoveries. Throughout the 19th century, Stonehenge unfortunately suffered significant degradation. Because there was no legal protection, visitors frequently removed pieces of stone as souvenirs, carved names into the megaliths, or simply disrupted the site. Archaeological interest in prehistoric Britain was increasing during this period, but there remained little consensus or infrastructure to support systematic conservation. The Antrobus family, though not archaeologists nor scholars, recognized Stonehenge’s historical importance and took steps to protect the site within the limitations of Victorian-era understanding and practice. Under Sir Edmund Antrobus’s ownership, modest preservation efforts were initiated. These included hiring local caretakers to monitor the monument and restricting unfettered public access to reduce vandalism. The family also allowed limited archaeological investigations, though the methods used would not meet modern scientific standards today (Greaney). The Antrobus ownership of Stonehenge marked a transitional period for the site. Although their preservation efforts were not comprehensive, the family’s actions helped stabilize Stonehenge during a time when few legal or governmental mechanisms existed to protect such sites. In this way, their ownership served as a bridge between centuries of neglect and the more formalized conservation practices that would come. During this time period, life was relatively hard for rural communities in Wiltshire. The Industrial Revolution hadn’t brought much prosperity to agricultural laborers, education was minimal, and most villagers had little interaction with Stonehenge except for shepherding nearby. However, this was also the age of Romanticism and Victorian curiosity, meaning increasing numbers of upper-class visitors came to the site, often on the new railways. The contrast between wealthy landowners and impoverished locals was stark. Locals might serve as guides or caretakers but had little agency in the monument’s fate (“Agriculture…”).

Sources “Agriculture 1793-1870.” A History of the County of Wiltshire. Ed. Elizabeth Crittall (London, 1959), British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol4/pp65-91. Greaney, Susan. “Stonehenge: A Monumental Auction.” English Heritage, 20, Sept. 2015, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/inspire-me/blog/blog-posts/stonehenge-monumental-auction/. |

Layna Henry |

| 1881 | Opening of the Natural History MuseumThe Natural History Museum officially opened in 1881 and quickly became a cornerstone of scientific and educational life in London. Designed by Alfred Waterhouse in the Romanesque style, the museum was established to house the British Museum's natural history collections, which had outgrown their former home. It reflected Victorian values of exploration, classification, and education, and its establishment highlighted Britain's role as a global power with a vast imperial reach. The museum's location in South Kensington placed it at the heart of what was dubbed "Albertopolis," a hub for arts and sciences funded and envisioned by Prince Albert. This area included institutions such as the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal Albert Hall. Its placement within the borough attracted not just scholars and scientists but also middle-class families, schools, and tourists, marking a democratization of knowledge and cultural engagement. Local demographics shifted to support this cultural growth. South Kensington saw an increase in infrastructure, transportation access, and population diversity. Builders, engineers, and service workers moved in to support the growing museum sector. The museum’s educational programs and free public access played a key role in raising scientific literacy among the general public. "History of the Museum." Natural History Museum, www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/history.html. Accessed 21 Apr. 2025. |

Hailey Burchfield |

| Oct 1884 | The Adoption of the Greenwich MeridianWith the study of navigation and astronomy as a major focus of the prior century, many remained dedicated to solving the issue of inconsistent longitude as many places measured it at different points. To do this, officials had to determine the best geological location for a point zero and to rationalize the measurement of time across the globe (Dolan).

The inception of the train system in the 1830s introduced a need for a stricter time system. This way rail companies could communicate across the country and run efficiently. The need for different time zones in North America also forced a stricter sense of time keeping (Dolan). The needs of geographers, navigators, and astronomers were all considered. According to Sandford Fleming, a railway engineer invested in reforming the time system, published a paper in 1879 in which he analyzed the meridians ships from around the world would use. He found that the Greenwich meridian was utilized by 65% of ships that used the main eleven meridians, making it the primary meridian. The top second and third meridians, Paris and Cadiz, were utilized by 10% and 5% respectively (Dolan). This study offered logical reasons as to why the Greenwich Meridian was a prime choice for the standard meridian.

In October 1884, U.S. President Chester Arthur invited delegates from 25 nations to meet in Washington, DC for the International Meridian Conference (The International…”). At this conference, seven resolutions were enacted:

All except France had accepted the Greenwich meridian after this conference (“History”). Progress in implementation was slow-going, especially with the transition from astronomical time to current time. However, France was the first to place a transmitter on the Eiffel Tower, taking the first step to widely disseminate time signals. To solidify a leadership role, Paris adopted Greenwich Mean Time in 1911 (Dolan).

The adoption of the Greenwich Meridian appears to be a pride point for some of those on the peninsula. For example, the Plume of Feathers, a pub that’s been around since 1961, proudly includes this in their history section, “In 1884 Greenwich’s meridian was adopted by the world as the prime meridian of the world (except the French, who continued to use the Paris one until 1911) and in that moment the Plume of Feathers became the first pub in the Eastern hemisphere (or at least one of them). And to this day it continues to serve beer and food on its original site, which now sits on the edge of the UNESCO Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site” (“History”).

Works Cited: Dolan, Graham. “The Adoption of a Prime Meridian and the International Meridian Conference of 1884.” Greenwich Meridian, http://www.thegreenwichmeridian.org/tgm/articles.php?article=10 “History of the Plume.” The Plume of Feathers, https://plumegreenwich.com/history “The International Meridian Conference, Washington, 1884” Greenwich Mean Time, https://greenwichmeantime.com/articles/history/conference/ |

Emera Gregor |

| Aug 1888 to Nov 1888 | GHASTLY MURDER IN THE EAST END: Jack the Ripper terrorizes WhitechapelOne of the most famous serial killers in history, Jack the Ripper, a psuedonym used to sign several letters, is presumed to be responsible for at least a dozen murders between April 1888 and July 1889, but only five, all committed in Whitechapel in 1888, were linked to a single culprit by police. Dubbed "The Canonical Five," these victims were Mary Ann Nichols (August 31), Annie Chapman (September 8), Elizabeth Stride (September 30), Catherine (Kate) Eddowes (September 30), and Mary Jane Kelly (November 9). All of them were believed to be prostitutes, murdered while soliciting on the street, except for Kelly, who was found murdered in her own home. In all five cases, the victim's throat was cut, and the bodily was mutilated with a level of sophistication that suggested the killer knew their anatomy. In her 2019 book, Hallie Rubenhold adamantly argued that only Kelly was a verifiable prostitute, and while Stride resorted to such on occasion, had not been at the time of her murder. She holds that "the notion that Jack the Ripper was a murderer of prostitutes was a consequence of the misogynistic and class-based prejudices characteristic of the Victorian era" (Jenkins). Alas, the entire case was handled poorly, perhaps contributing to why it went unsolved. With the industrial revolution came bigger and better printing presses, and as holds true even today, new outlets will report anything to sell papers. After the body of Mary Ann Nichols is found, The Star reported on "Leather Apron," the name they gave the killer. In their write-up, they pointed blame to Jewish butchers, thus sparking more anti-semitism within the district. Throughout the investigation, three letters were sent to police and press, two signed "Jack the Ripper," and the last signed "FROM HELL". The first, addressed to "The Boss, Central News Office, London, City," came the night of September 30th, 1888, following the murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes. The Cental News Agency has received the letter on the 27th, but waited two days to send it to the Metropolitan Police. The entirety of the letter is the author gloating about how he has yet to be caught, the police and press are idiots, he's rearing to kill again, and, this time, he's going to clip his victim's ears and send them to the police. The next day, a double murder, and, sure enough, Catherine Eddowes was missing part of her ear, but they were still intact, suggesting that her killer was interrupted. The second letter, dubbed the "Saucy Jack" letter, as that is what the author refers to himself as, appeared at the Central News Agency, in similar handwriting to the first. Short and sweet, he continues to boast about getting away with his crimes, mentions how he could not get the ears, and thanks police for "holding on" to his previous letter. Though letters kept pouring in after these were released to the public, there's one that many consider to be the final, legitimate letter. Signed "From Hell," the letter was addressed to the head of the Mile End Vigilance Committee, Mr. George Lusk, and contained part of a kidney, the rest supposedly eaten by the author, per his own words. Conflicting opinions on whether or not the kidney was human, on top of horrific misreporting, makes authenticating the letter difficult. As far as I know, it was a prank by some college students. Alas, this only furthers the point that the mass media coverage may have impeded the investigation. There has been no end to "possible" suspects, but there are three that are the most cited, and, in my opinion, do make the most sense. Those are: Montague Druitt, a barrister and teacher who was said to have an "interest in surgery", proclaimed insane, and was found dead some time after disappearing following the final murder; Michael Ostrog was a Russian criminal and physician who, apparently, displayed "homicidal tendencies," for which he was admitted to an asylum; and, finally, Aaron Kosminski, a Polish Jew who lived in the Whitechapel area, reportedly hated women (especially prostitutes), and was also admitted to a psychiatric hospital following the last murder. Jenkins, John Philip. "Jack the Ripper". Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Jan. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jack-the-Ripper. Accessed 25 April 2023. Jones, Richard. “The Dear Boss Letter - Yours Truly Jack the Ripper.” The Dear Boss Jack The Ripper Letter., https://www.jack-the-ripper.org/dear-boss.htm. Jones, Richard. “The from Hell Letter - Received by George Lusk.” The From Hell Catch Me When You Can Letter, https://www.jack-the-ripper.org/from-hell.htm. Jones, Richard. “The Jack the Ripper Timeline.” The Timeline For The Jack The Ripper Murders, https://www.jack-the-ripper.org/timeline.htm. |

Logan Wertz |