Executive Summary

Within this COVE gallery, you will find our essay on defining masculinity in relation to The Little Lame Prince and the Victorian period. Drawing on sources about muscular Christianity and the domestic sphere, we examine how the story challenges traditional ideals of manhood. Through the texts and illustrations we reference, we argue that The Little Lame Prince promotes empathy and emotional depth over physical strength, redefining masculinity through compassion, imagination, and a quiet spiritual awakening rooted in understanding.

Our selected illustrations, paired with analysis from multiple sources, offer a diverse exploration of how visual representations engage with and challenge Victorian gender norms. Our commentary traces how these images contribute to the story’s broader redefinition of what it means to be a man.

Our chosen periodical, The Englishwoman’s Review: A Journal of Woman’s Work, explores masculinity in Victorian culture by arguing that intellectual differences between men and women stem from environment, not biology, calling for a rejection of rigid gender roles.

For our journal article, “Fairy-Tale Bodies: Prosthesis and Narrative Perspective,” we examine how Prince Dolor’s disability shapes his emotional and moral development. Kylee-Ann Hingston argues that Dolor achieves an alternative form of manhood through personal growth, challenging Victorian ideals of masculinity.

And at the end of our gallery, we have included a written reflection on the research that went into the illustrations and their relationship with masculinity. This project taught us a lot about the strict gender roles of the Victorian era, and how disability factored into their societal conceptions of masculinity.

Periodical: The Englishwoman’s Review: A Journal of Woman’s Work

The periodical derives from a paper read at the Manchester Ladies’ Literary Society meeting in March 1868. Lydia E Becker, the society’s President, questions in her reading whether “there [is] any specific distinction between male and female intellect” (483). The periodical highlights the minute differentiations of traditional masculine and feminine roles, particularly in society. As the title suggests, the author emphasizes men's and women’s “process of reasoning,” “intellectual labour,” restraints, and freedoms (Becker 483-484). The periodical argues that these societally assigned attributes do not “extend to [the] mind;” in actuality, gendered traits are “traceable to the influence of the different circumstances” in which an individual is raised (484). The author argues that men and women can have as many attributes in common between two men or two women (484). The article emphasizes the importance of developing a well-rounded character or skill set which contributes to furthering the human species, regardless of gender or sex (490).

When we look at The Little Lame Prince and His Traveling Cloak, readers recognize how Prince Dolor maintains traditional masculinity and femininity attributes. The periodical argues that an individual’s behaviour depends heavily on their environment, including maternal/paternal figures, colour exposure, practical education, etc. Prince Dolor, although raised on the affection of his godmother, only has his tutor/nurse as an educator and his only company. The story illustrates Prince Dolor’s frequent alone time; the value of private play causes his consciousness and inner voice to form faster than children of his age:

“So the next day he opened his eyes with the sun, and went with a good heart to his lessons. They has hitherto been the chief amusement of his dull life… how ashamed my godmother would be if I grew up a stupid boy!” (Craik).

The article views boys as more “encouraged to develop their bodily powers, to mix with the world,” and to take on ambitious roles of power in society (Becker 488). Women, however, are encouraged to do the opposite and expand their knowledge privately without being boastful about their achievements (488). The periodical describes human males as masculine and human females as feminine, but psychology acknowledges there are masculine and feminine attributes within both genders (490). The article even argues that overlap is imperative to the furthering of many species, including the human race:

“...they may help to disabuse us of the notion that superiority in strength is necessarily masculine — every botanist being aware that female plants are quite as strong and big as male ones of the same species” (485).

Prince Dolor’s position as a Prince, and then King provides him with the opportunity for an expensive education; the article references “education and training” as the main divergence between men's and women’s vocations, daily habits, and “the things each has got to do” (478-488). Without his upbringing and personal perspective, Prince Dolor would not be the same compassionate, kind, and intelligent King he is at the story’s end without his masculine and feminine characteristics.

Journal Article/Book Chapter: Fairy-Tale Bodies: Prosthesis and Narrative Perspective

Within this book chapter, “Fairy-Tale Bodies: Prostheses and Narrative Perspective in Dinah Mullock Craik’s The Little Lame Prince”, Kylee-Ann Hingston dissects the way that narrative conventions were incorporated in Victorian writing to aid in the understanding of disabled bodies. Focusing primarily on The Little Lame Prince, Hingston discusses how Craik employs genres such as the parable, fairy tale, and Bildungsroman to portray Prince Dolor in a way that unconventionally relates to Victorian ideals of disability and masculinity (Hingston 140). Hingston posits that Dolor’s maturity brought on by his experience with disability and isolation allows him to develop into a king who can be perceived with some sense of acceptance within the book (145).

In terms of the chapter’s strengths, I greatly appreciate its discussion of the criticism surrounding The Little Lame Prince and its socio-historical implications, as well as its inclusion of how Dinah Craik’s relationship with disabled people and disability studies helped to inform her work. More specifically, critics such as Alan Richardson provide insightful commentary, such as his views of Dolor’s gender identity being presented as a “softened masculinity” (145). These points serve to provide a more in-depth contextualization of Dolor’s character as it existed within Victorian society. In terms of weaknesses, I find that the positioning of Craik’s use of narrative conventions along with the notion of prosthetics made it a bit difficult to find direct connections to the topic of masculinity, especially as Hingston disagrees with some of the arguments posited by certain gender critics of the book.

By focusing heavily on Dolor’s progression through his childhood and onto kingship, Hingston’s chapter lays the foundation for discussing the relationship between masculinity and disability in The Little Lame Prince. Considering this reading alongside Victorian ideals of masculinity, one sees how Dolor achieves manhood in a way that deviates from the societal norm and exposes Victorian anxieties surrounding gender expression and disability. With the addition of Craik’s use of narrative conventions, it can be argued that his personal growth and maturity validate Dolor’s masculinity and kingship.

Reflection on the Assignment

This project taught us a lot about the strict gender roles of the Victorian era, and how disability factored into their societal conceptions of masculinity. It was surprising to learn just how exclusionary conversations about masculinity were during this period, with disability being discussed so rarely in relation to manliness. While researching this topic we found that the strong emphasis of physical strength that the Victorians tied to the idea of masculinity often left those who were physically disabled to be feminised and infantilized in literature. This provided a challenge for us as we completed this project. It was not easy to find images which depicted the Lame Prince as being masculine or strong. Often the Prince was illustrated to look fragile and delicate. This gave us a new perspective on disability and masculinity.

The most interesting part of this assignment was looking through different periodicals from the Victorian era. It was helpful to see the way masculinity and disability were understood during this period, and how that translated to the Little Lame Prince. Views on how men should act in society, as well as how we understand disability have changed so much since the Victorian era, so it was important for us to look through these articles to understand the ideals of the time. By understanding the older texts, we were able to take ourselves out of our current understanding of the topic we had chosen and see it through the lens of Victorian society. This was especially important when looking at the Little Lame Price because it allowed us to see exactly how Craik was challenging not only the common views of masculinity at the time, but how people understood disabled people and their abilities to lead.

Works Cited

Becker, Lydia E. "II.-Is There Any Specific Distinction between Male and Female Intellect?" The Englishwoman’s Review: A Journal of Woman’s Work, no. VIII, 1 July 1868, pp. 483+. Nineteenth Century UK Periodicals, link-gale-com.ledproxy2.uwindsor.ca/apps/doc/DX1901996096/NCUK?u=wind05901&sid=bookmark-NCUK&xid=84ffc03b.

Craik, Dinah Maria Mulock. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by Hope Dunlap, Yesterday's Classics, 2017. Yesterday's Classics, yesterdaysclassics.com/books/the-little-lame-prince-by-dinah-maria-mulock/. Front cover image.

---. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by Albert Whitman, Albert Whitman & Co., 1927, p. 113. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/littlelameprince00crai_5/page/112/mode/2up.

---. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by Albert Whitman, Albert Whitman & Co., 1927, p. 123. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/littlelameprince00crai_5/page/123/mode/2up.

---. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by Earl Mayan, Harper & Row, 1965. Image caption: "Suppose I were a knight; then I should be obliged to ride out and see the world."

---. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by Etheldred B. Barry, D.C. Heath & Co., 1910, p. 113. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/littlelameprince00crai/page/112/mode/2up.

---. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by Etheldred B. Barry, D.C. Heath & Co., 1910, p. 127. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/littlelameprinc01craigoog/page/n139/mode/2up.

---. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by Etheldred B. Barry, D.C. Heath & Co., 1910, p. 138. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/littlelameprince00crai/page/138/mode/2up.

---. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by J. McL. Ralston, MacMillan and Co., 1904, p. 24. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/littlelameprince0000unse_b9p0/page/24/mode/2up.

---. The Little Lame Prince. Illustrated by Rand McNally, Daldy, Isbister and Co., 1909. Image description: "He was rather frightened, and the face, black as it was, looked kindly on him."

Hingston, Kylee-Ann. "Fairy-Tale Bodies: Prostheses and Narrative Perspective in Dinah Mulock Craik’s The Little Lame Prince." Articulating Bodies, Liverpool UP, 2019, pp. 139–160. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvqmp1gs.9.

McKay, Brett, and Kate McKay. "When Christianity Was Muscular." The Art of Manliness, 13 Sept. 2016, artofmanliness.com/character/knowledge-of-men/when-christianity-was-muscular/.

Philipose, L. "The Politics of the Hearth in Victorian Children’s Fantasy: Dinah Mulock Craik’s The Little Lame Prince." Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 3, 1996, pp. 133–139. Project MUSE, doi.org/10.1353/chq.0.1268.

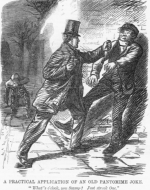

Punch. "A Practical Application." Punch, vol. 43, 20 Dec. 1862, p. 254. Reprinted in Michele Cohen, "Dueling, Conflicting Masculinities, and the Victorian Gentleman," Journal of British Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, Apr. 2006, pp. 283–305. Cambridge UP, doi.org/10.1086/499791.

Richardson, Alan. “Reluctant Lords and Lame Princes: Engendering the Male Child in Nineteenth-Century Juvenile Fiction.” Children’s Literature (Storrs, Conn.), vol. 21, no. 1, 1993, pp. 3–19, https://doi.org/10.1353/chl.0.0307.