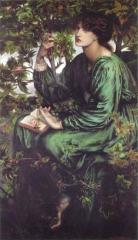

Artistry had a longstanding foothold in European society, as famous artists such as da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt were dedicated figures and perceived as more than man. In 1848 a group of English painters, poets, and art critics founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a collective experience designed to return nineteenth century European art to that of the Quattrocento Italian art. The Quattrocento period refers to all Italian art created between 1400-1499 which consisted of an abundance of detail, vivid color aesthetics and complexity. The group directly rejected the Mannerist artists, the form of art that gained exposure around 1520 succeeding Raphael and Michaelangelo. Specifically the group rejected the teachings of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the founder of the English Royal Academy of Arts. They found the teachings and artistry of Reynolds to be lackadaisical, thoroughly absent of complexity which to the Brotherhood was a direct insult to artistry as a whole. The group was subject to harsh criticism as they were seen as very backwards facing, understandably so as the world of art is constantly looking forward yet this group fought viciously to return to a more medieval style of painting. One of the groups’ most notorious critics, Charles Dickens, who had become thrown into the spotlight of Victorian England found the portrayal of the Holy Family “blasphemous” and found their entire style backwards- looking and simply ugly.

Ah, Basil, I recently viewed the work from John Everett Millais and I must say it is most certainly butter upon bacon. His Christ in the House of His Parents holds no standing in my opinion, in the cast contrary to yours dear Basil. You exercise such amazing beauty unlike that absurd Pre- Raphealite Brotherhood, how grotesque and backwards! I have no such understanding for artistry that seeks to live in the past, unlike your portraits. Don’t sell me a dog! I would be half rats to consume any more abominations from that group, how dare they condemn the teachings of Sir Joshua Reynolds. Perhaps I am just cynical, or perhaps I am astonishingly self aware. Alas, art is for the artistry’s sake and you, Basil, are an artist unlike any other.

Works Cited

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. (2020, October 03). Retrieved October 27, 2020, from en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pre-Raph…

Wilde, Oscar. (1890) The Picture of Dorian Gray. [online] Available from: Cove Studio [Accessed September 2020]

.

.